This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

When I teach and write about Iliad 6 I usually find myself spending too much time thinking about Diomedes’ exchange with Glaukos and then breaking hearts with discussions of Hektor, Andromache, and Astyanax at the book’s end. In talking about the former, I typically spend most of my time going through Glaukos’ remarkable story, both for its content (Bellerophon!) and its impact (Diomedes declares them guest-friends). But before Diomedes delights in Glaukos’ ancestry, he tells his own story from myth.

Homer, Iliad 6. 130-140

For not even the son of Dryas, mighty Lykourgos,

Lasted long once he began to strive with the heavenly gods.

He;’ the one who chased the nurses of maddening Dionysus

Down the Nysian hill–all of them were dropping

Their wands to the ground because they were beaten

By man-slaying Lykourgos with a cattle-goad.

And Dionysus was frightened, so he immersed himself

In the salty waves where Thetis rescued the frightened child.

A powerful tremor had overcome him from the man’s shouting.

After that, the gods who live easily hated him

And Kronos’ son left him blind. And he didn’t last very long

After that, once he became hateful to all the immortal gods.”οὐδὲ γὰρ οὐδὲ Δρύαντος υἱός, κρατερὸς Λυκόοργος,

δὴν ἦν, ὅς ῥα θεοῖσιν ἐπουρανίοισιν ἔριζεν·

ὅς ποτε μαινομένοιο Διωνύσοιο τιθήνας

σεῦε κατ᾿ ἠγάθεον Νυσήϊον, αἳ δ᾿ ἅμα πᾶσαι

θύσθλα χαμαὶ κατέχευαν, ὑπ᾿ ἀνδροφόνοιο Λυκούργου

θεινόμεναι βουπλῆγι. Διώνυσος δὲ φοβηθείς

δύσεθ᾿ ἁλὸς κατὰ κῦμα, Θέτις δ᾿ ὑπεδέξατο κόλπῳ

δειδιότα· κρατερὸς γὰρ ἔχε τρόμος ἀνδρὸς ὀμοκλῇ.

τῷ μὲν ἔπειτ᾿ ὀδύσαντο θεοὶ ῥεῖα ζώοντες,

καί μιν τυφλὸν ἔθηκε Κρόνου πάϊς· οὐδ᾿ ἄρ᾿ ἔτι δήν

ἦν, ἐπεὶ ἀθανάτοισιν ἀπήχθετο πᾶσι θεοῖσιν.

This is one of the few times in the Iliad where we find Dionysus mentioned at all. Indeed, the absence of Dionysus in our extant epic poetry is so marked that it led earlier generations of scholars to buy in to the Dionysian narrative of “a new god from the east”. (This argument was largely dispelled by the decipherment of Linear B which, surprise, shows ample evidence of Dionysus). One explanation for this absence has been generic: according to some, epic is properly the province of more rational gods like Athena and Apollo and Dionysus is more proper to lyric and tragedy. I am uncertain about this for two reasons: Apollo is not necessarily rational and we do have epic fragments (e.g. Panyasis) that shows wine and the forces of Dionysus as alive and well in epic verse.

If I were forced to give an answer on the spot about Dionysus’ absence from epic, I would suggest two thematic answers. First, as Elton Barker and I explore in Homer’s Thebes, the Iliad is interested in establishing the metaphysical boundaries of mortal human life. Even Herakles, as Achilles opines, is subject to death in its world view. Dionysus, as a child of a mortal mother and Zeus who becomes a god, challenges this fundamental feature of epic poetry. If mortals can become immortal, what’s the point of fighting, dying, and earning kleos. My second ‘idea’, which is much less well formed and perhaps just nonsense, is that our notion of Dionysus’ importance to the Greek pantheon might be skewed by the Athenocentric nature of our evidence for ancient Greece. Dionysus was extremely significant in Athenian cult and ritual (especially around Tragedy). I have a suspicion that the gods present in Homeric epic are there as much for their Panhellenic appeal as their generic importance.

In her Homeric Encyclopedia (2011) article on the topic, Renate Schlesier notes that Dionysus appears only four times in the Homeric epics, typically in situations “loosely associated with love and/or violent death” (210; to be fair, most situations in Homer could fall under this category).She adds that Dionysus does not seem to be a wine go in Homer, but that the language and motifs around him does seem to imply a knowledge of Maenadism.

The passage in the Iliad is explained as part of Dionysus’ conventional exile from Thebes and journeys through the east. A scholion summarizes it.

Schol. D ad, Hom. Il. 6.130

“Dionysus, the child of Zeus and Semele, happened to be receiving purification under the guidance of Rheat among the Kybeloi of Phrydia. Once he completed the rites and received his acoutrement from the goddess, he traveled all over the world. He obtained his choruses and honors, while people were leading him everywhere. When he was present in Tharce, Lykourgos, son of Dryas, caused him pain, Hera was despising him, and drove him from the land with a gadfly. She attacked him and his caregivers. They happened to be engaging in sacred rites along with him. Driven by a god-made whip, he was rushing to punish the god. But [Dionysus] leapt into the sea beccause of fear where Thetis and Eurynome accepted him. Lykourgos did not commit irreverance without punishment. He paid a penalty mortals do.--for Zeus took his eyes from him. Many record this story, but Eumelos told the story first in his Europia.”

Διόνυσος, ὁ Διὸς καὶ Σεμέλης παῖς, ἐν Κυβέλοις τῆς Φρυγίας ὑπὸ τῆς ῾Ρέας τυχὼν καθαρμῶν, καὶ διαθεὶς τὰς τελετὰς, καὶ λαβὼν παρὰ τῆς θεᾶς τὴν διασκευὴν, ἀνὰ πᾶσαν ἐφέρετο τὴν γῆν, χορειῶν τε καὶ τιμῶν ἐτύγχανε, προηγουμένων τῶν ἀνθρώπων. Παραγενόμενον δὲ αὐτὸν εἰς τὴν Θρᾴκην, Λυκοῦργος ὁ Δρύαντος λυπήσας, ῞Ηρας μίσει, μύωπι ἀπελαύνει τῆς γῆς. καὶ καθάπτεται αὐτοῦ καὶ τῶν τούτου τιθηνῶν. ἐτύγχανον γὰρ αὐτῷ συνοργιάζουσαι. Θεηλάτῳ δ' ἐπελαυνόμενος μάστιγι, τὸν θεὸν ἔσπευδε τιμωρήσασθαι. ῾Ο δὲ ὑπὸ δέους εἰς τὴν θάλασσαν καταδύνει, καὶ ὑπὸ Θέτιδος καὶ Εὐρυνόμης ὑπολαμβάνεται. ῾Ο οὖν Λυκοῦργος οὐκ ἀμισθὶ δυσσεβήσας, ἔδωκε τὴν ἐξ ἀνθρώπων δίκην. ἀφῃρέθη γὰρ πρὸς τοῦ Διὸς τοὺς ὀφθαλμούς. Τῆς ἱστορίας πολλοὶ ἐμνήσθησαν, προηγουμένως δὲ ὁ τὴν Εὐρωπίαν πεποιη κὼς Εὔμηλος.

Christos Tsagalis provides the most in-depth discussion of this passage (that I know of). In The Oral Palimpsest, Tsagalis treats this passage first as a mythological paradeigma but then charts the language, especially the participle μαινομένοιο. Christos combs through similar language in the iIliad to identify a thematic pattern that shows “interplay between the Dionysias metaphor in the myth of Lycurgus…and the meeting between Andromache and Hektor” (37). He draws attention to both Lykourgos and Hektor sharing the epithet “man=slaying”, Andromache being compared to a maenad, the fear felt by baby Dionysus and Astyanax, and the liminal dramatic space where the action of the myth and the meeting of Hektor and Andromache take place. Tsagalis uses this analysis–and more that probes the couple’s connection to Thebes–to suggest both the Dionysus does in fact belong to other poems and non Ionian traditions. In addition, the association of Andromache with a maenad engages with a larger mythical tapestry, “ changing (as far as Andromache is concerned) an Amazon with maenadic and warlike origins into a suffering wife and mother” (64).

Tsagalis was not the first to treat this scene, of course. M.B. Arthur sees the comparison as indicated that Andromache is moved out of her normal state of mind by anxiety and grief. Charles Segal demonstrates how Homeric language has been shifted to accommodate this image. I think we also need to consider the valence of the image of audiences who would have been more familiar with the range of meaning associated with Maenads. Imagine an audience familiar with stories like the Bacchae. Andromache as a maenad may be out of her mind from an authoritative male perspective, but she may also be considered rightfully so from a cosmic perspective. Her out-of-mindness stands both to mark her straining to break from the limited agency the siege of Troy (and her marriage to Hektor) imposes while also anticipating her ultimate marginalization by grief and his loss.

If we treat the internal references as a kind of simile where Hektor=Lykourgos and Astyanax=Dionysus, there may be additional pathos to consider. Hektor is clearly not god-hated, but he is a king who cannot stay within limits. The difference here is that Hektor commits no sacrilege and the infant child does not go on to be rescued by a goddess of the sea.

Regardless of the precise interpretation we offer, this is a good example of how fluidly integrated the motifs and themes of epic poetry are on both large and small scales. The story of Lykourgos in Diomedes’ speech is a lesson about angering the gods that Glaukos picks up on and responds to in his own narrative where his Bellerophon becomes hateful to the gods despite performing heroic deeds. So, the story Diomedes offers Glaukos is not a simple message to his addressee, but it is a dynamic narrative Glaukos ‘reads’ and uses to ‘decode’ the challenge Diomedes presents in the text. The correspondence between this scene in the middle of book 6 and the later presentation of Hektor, Andromache, and Astyanax relies on audience memory and interpretation, triangulating a level of understanding that requires both a knowledge of poetic convention and a sensitivity to the stories at play.

Prior posts on Iliad 6

Structure and Stories: Reading Iliad 6: Killings and Homeric ‘obituaries’; the structure of Book 6

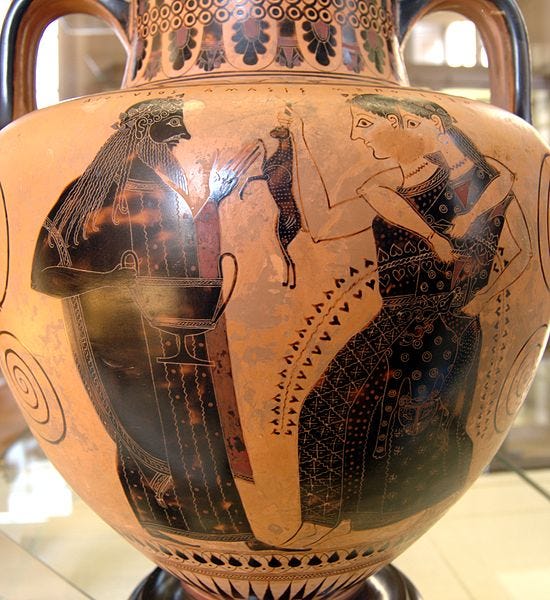

War Crimes: Iliad 6, Infanticide, and the Mykonos Vase: Homeric Violence; Child killing; enslavement; sexual violence

Mind Reading and Stolen Wits: The Encounter of Diomedes and Glaukos in Iliad 6

A short bibliography

Arthur, M.B. “The Divided World of Iliad VI.” In Reflections of Women in Antiquity, Helene Foley ed. New York: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, 1981, 19-44.

Lightfoot, Jessica. “Something to do with Dionysus ? : dolphins and dithyramb in Pindar fragment 236 SM.” Classical Philology, vol. 114, no. 3, 2019, pp. 481-492. Doi: 10.1086/703823

Davies, Malcolm. “Homer and Dionysus.” Eikasmos, vol. 11, 2000, pp. 15-28.

Segal, C. “Andromache’s Anagnorisis: Formulaic Artistry in Iliad 75 (1971): 33-57.

Suter, Ann. “Paris and Dionysos: iambos in the Iliad.” Arethusa, vol. 26, 1993, pp. 1-18.

Tsagalis, Christos. 2008. The Oral Palimpsest: Exploring Intertextuality in the Homeric Epics. Hellenic Studies Series 29. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_TsagalisC.The_Oral_Palimpsest.2008.

What I noticed about book six this time around was how bizarre and hopeless Helenus’ idea to pray to Athena was. I mean, we’ve just seen in Book 5 Athena how greatly Athena is helping Diomedes. Does Helenus *know that* and think for that very reason they should attempt to propitiate her? Or does he have no idea?

Additionally, it’s interesting how curt Athena’s reply to her offering is. We’re told *three times*, around ten lines each, what the ceremony is like (Helenus tells Hector, Hector tells Hecabe, and the narrator tells us) and Athena gives her response in one line, 311 — no.

And a point of fact I hadn’t noticed before: that the garment that they sacrifice to Athena is actually one that has been given to Hecabe by Alexandros, which he obtained during the same trip on which he abducted Helen. If Hecabe had chosen a different garment, one wonders, would Athena have answered differently?

But I think the answer is no, and that what we’re intended to see here is how doomed the Trojans are: praying to the wrong god about the wrong thing with the wrong offering.

Maybe that ties into your Gluakos-Diomedes point about being hateful to the gods?

Finally, as you remark on “Structure and Stories” this book is uniquely filled with women. We get all the female “stars” (Hecabe, Andromache, Helen) as well as a bunch of handmaidens and a ceremony to a female goddess conducted by “women of honor.” And then we see both Paris and Hector with respect to their women: Hector twice turning down mother and wife’s suggestions that he rest, Paris being cajoled by Helen to get back into the fight. You couldn’t have scenes such as these on the Greek side, where there are no such women, nor would it be so poignant from the point of view of the victors.