“For poets certainly tell us that they bring us songs by drawing from the honey-flowing springs or certain gardens and glades of the Muses just like bees. And because they too are winged, they also speak the truth.”

Λέγουσι γὰρ δήπουθεν πρὸς ἡμᾶς οἱ ποιηταί, ὅτι ἀπὸ κρηνῶν μελιρρύτων ἢ ἐκ Μουσῶν κήπων τινῶν καὶ ναπῶν δρεπόμενοι τὰ μέλη ἡμῖν φέρουσιν ὥσπερ αἱ μέλιτται. καὶ αὐτοὶ οὕτω πετόμενοι, καὶ ἀληθῆ λέγουσι, Plato, Ion

“Aristotle records the claim that Homer was born from a demon who danced with the Muses.”

᾿Αριστοτέλης δὲ ἱστορεῖν φησιν † λητὰς ἔκ τινος δαίμονος γεγενῆσθαι τὸν ῞Ομηρον ταῖς Μούσαις συγχορεύσαντος. Vitae Homeri [demon = daimon = a god]

When I start working on Homer with students, one of the first things I do is discuss what the epics are. I think this is important because they are fraught with historical weight thanks to their inclusion in multiple canons; but they also present ample opportunities for confusion because they derive from very different aesthetic principles than a modern novel or movie.

The hardest thing for me to come to terms with over the years has been that the epics are different things to different people over time. They are diachronic objects, even if we insist that they came together in the form we have them at a particular time and place. So, any fair approach to the Iliad or the Odyssey needs to understand that the epics have been different interpretive objects to different audiences over time and that the assumptions that attend them in each period set up distinct expectations based on often unarticulated aesthetics.

There are so many things to say about the “Homeric Question” that it could (and does) fill many books. The variations on the questions include how and when were the epics ‘written’ down; whether they are ‘by’ the same ‘author’; what the importance is of the oral tradition as opposed to the written one; if we have the ‘same’ versions of the texts discussed in antiquity, and so on. (And each of these topics is complicated in turn by how we define or gloss the words I put in scare quotes.)

I am not even going to try to answer all these questions, instead I want to give a brief overview of what I see as the (1) primary tensions governing the Homeric problems, (2) the transmission models that have produced the texts we possess; (3) the stages I think are important for shaping these diachronic objects; and (3) more or less correlative stages of reception. In a later post I will expand more on what I think all of this means for teaching Homer.

Tensions

I think there are five primary tensions that warp the way we think and talk about our Homeric problems: (a) Ancient Biographical traditions; (b) notions of unity vs. disunity (Unitarians vs. Analysts); (c) prejudices inherent in the dichotomy of orality vs. textuality; (d) cultural assumptions about authorship (tradition vs. the idea of monumental poets); (e) and the impact of Western chauvinism in forestalling the adoption of multicultural models. ‘Homer’ was an invention of antiquity: there’s no good reason to think that one ‘author’ in the modern sense is responsible for the Homeric epics (a); instead, we have ample reason to believe otherwise, from the scattershot madness of ancient biographies (see Barbara Graziosi’s Inventing Homer and the discussions in Gregory Nagy’s Homer the Preclassic; for much more positivistic textualist accounts, see M. L. West’s The Making of the Iliad or The Making of the Odyssey) to all the evidence we have for composition in performance (start with Milman Parry’s Studies in Homeric Verse Making and Albert Lord’s The Singer of Tales).

The fact remains, however, that after Plato (and certainly by the time of Aristotle) most authors in antiquity treated Homer as an author responsible for the creation of the Iliad and the Odyssey with little compunction for challenging the attribution. (But prior to Aristotle, there was much more given to Homer than a mere two epics.) While there are echoes and whispers to the contrary (and, indeed, an entire scholarly tradition from Alexandria through to Modern Germany trying to shoehorn Homer into the shape of an author), it really isn’t until the end of the 18th Century and the publication of F.A. Wolf’s Prolegomena ad Homerum that scholars stopped worrying about which island Homer was from and started really questioning the nature of the text they received.

By the end of the 19th century, (b) Homeric studies had split into camps that argued that the epics we have are products of editors stitching them together (Analysts) or that the epics are Unitary creations of a genius (or two; Unitarians) and the Analysts were clearly winning: such is the confusion, the repetitions, the omissions, and (apparent) inconsistencies of the Homeric texts (that word there is important). It was really the revelation of oral-formulaic theory and the articulation of composition in performance that broke this logjam.

Oral-formulaic theory shows that long, complex compositions can be created without the aid of writing and helps us to understand in part that the aesthetic ‘problems’ of the Homeric epics are features of their genesis and performance context and not problems. (So, features not bugs of epic poetry.) Homeric scholarship, however, spent nearly a century establishing that this was actually the case leading us to the profound issues of the 20th century (c+d), first, resistance to oral formulaic theory (on which see Walter Ong’s Orality and Literacy or John Miles Foley’s How to Read an Oral Poem) and then second, debate over how oral the Homeric epics are. One of the favorite canards for the textualists to toss about is that oral-formulaic poetry posits “poetry by committee.” From this perspective, only an individual author could have produced the intricacies of meaning available in Homeric epic.

I contend that this is nonsense that misunderstands both oral formulaic theory and language itself. But who has time to argue that? The fact is that Homeric poetry as we have it comes to us as text and this text is oral-derived but has been edited and handled for centuries (ok, millennia) by people who think it is all text. No matter how we reconstruct its origins, then, we must treat it as a diachronic object that was textualized, that was treated as a text from a single author by editors for 2000 years, and whose inclusion in the canon has shaped both what we think verbal art should be like and what we think the epic is. (Nevertheless, since our culture is literate, literary, and prejudiced towards textualized ways of thinking, as redress we need to learn more about orality and performance based cultures.)

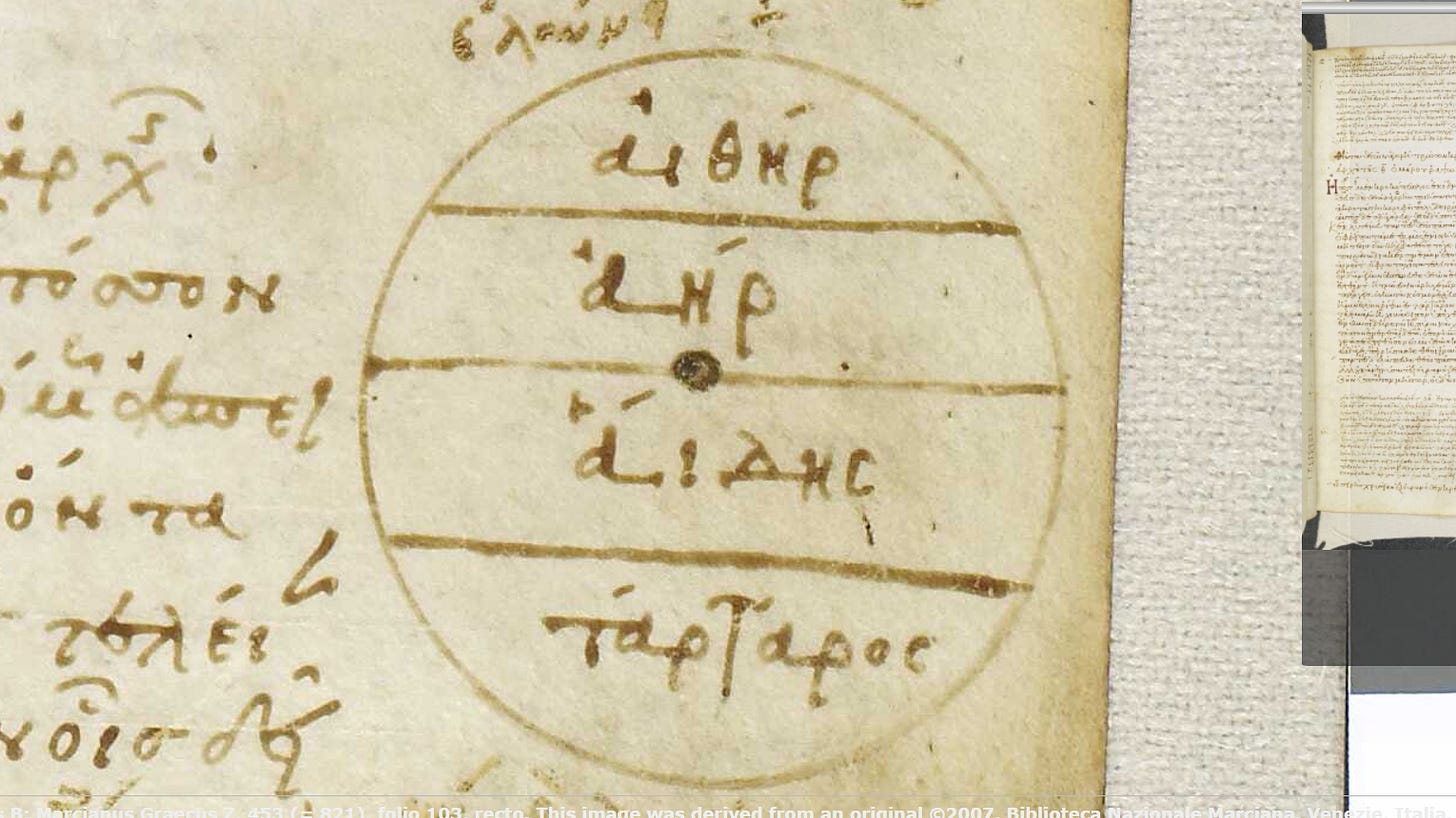

A final aspect of Homer that I believe we have far underestimated because of racist fantasies like the “Greek miracle” is its multiculturalism. The world of archaic Greece (and before) was heavily engaged with people from other language groups and cultures. Since the decipherment of the Gilgamesh poems, scholars have seen deep thematic and linguistic parallels between the remains of the ancient Near East and early Greek poetry. A lot of this is detailed well in M. L. West’s The East Face of Helicon; Mary Bachvarova’s From Hittite to Homer is revelatory in providing even more material from ancient Asia Minor. The Homeric epics we have are products of different cultures, different audiences, and often competing linguistic, political, and class ideologies over time. They are not the font and origin of culture; rather, they are a fossilized cross-section of intercultural change.

Transmission Models and Stages for the Epic

There are three primary transmission models that present different dates for the textualization of the Homeric epics.

1000-800 BCE Homer at the Origin of Culture (Barry Powell and Friends)

800-510 BCE Dictation Theories (Richard Janko; Minna Skafte Jensen; see Jonathan Ready’s recent book for an overview)

800-c. 280 BCE: Evolutionary Model (Gregory Nagy)

I lean really heavily toward the third option with one caveat, it still requires a bit of magical thinking or at least a suspension of disbelief. We don’t know how or when the epics we have were put down in writing, although it is clear from textual evidence that they went through ‘sieves’ or ‘funnels’ in Athens prior to the Hellenistic period and in Hellenistic libraries (and I will talk about Power and Publishing in a later post.)

To my taste, the two earlier models require equally magical thinking with somewhat more dismissiveness: the first requires an ahistorical and unlikely narrative for the adoption of writing in Greece and the promulgation of texts. It insufficiently considers the material conditions for the textualization of the epics and the adoption of the new technology for a performance form. (Like most arguments, it is driven by an ideology that encourages that magical thinking.) The second is easier to accept, but it does not account for motivations for dictation or the material conditions for preservation and dissemination. As Jensen observes, if the text were in fact written down during the 6th century, we have no evidence for its wide dissemination as a monumental text nor its use in literary reading apart from performance. The third option is the hardest to accept because of its complexity; but once accepted, it provides the most dynamic models of meaning-making available to Homeric interpreters.

The process and moment of epic textualization is an aporia–it is an unresolvable problem. Even if it were resolved, it would not change the history of the reception of the text. Rather than worry overmuch about the method and time of textualization, I think it is more useful to think about the impact of the epics being different things over time. So, I like to break the stages of these diachronic objects down as follows (and, to be clear, we have evidence for people engaging with the texts in the following ways.

Stages of performance, textuality, and fixity

Oral composition and Performance ?-5th century BCE

Canonization, Panhellenization 8th Century BCE through 323 BCE

Episodic engagement and occasional monumental performance, ?-4th Century BCE

Textualization, 6th-4th Centuries BCE

Editing and Standardization, 323 BCE-31 BCE (?)

Passage Use in Rhetorical Schools 280 BCE-? (5th Century CE? 12th century CE)

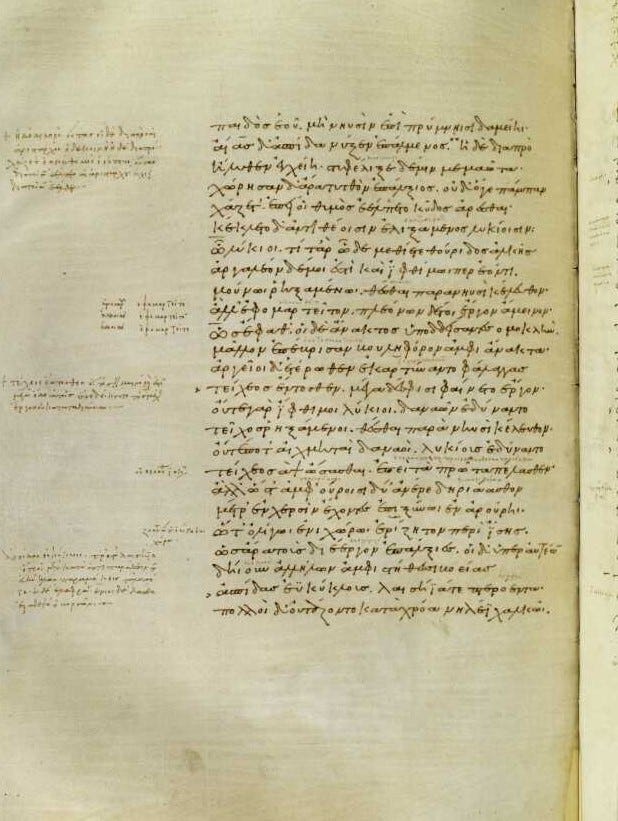

Creation of Synoptic Manuscripts we have, 9-12th Century BCE

These stages, to my mind, represent the full range of metamorphoses for the diachronic objects we currently possess, on a scale from least to most certainty. We have Byzantine manuscripts–they provide us with the texts we translate from to this day. We only have partial evidence for everything before that.

Reception Models

“What is lacking in Homer, that we should not consider him to be the wisest man in every kind of wisdom? Some people claim that his poetry is a complete education for life, equally divided between times of war and peace.”

Quid Homero deest, quominus in omni sapientia sapientissimus existimari possit? Eius poesim totam esse doctrinam vivendi quidam ostendunt, in belli tempora pacisque divisa, Leonardo Bruni de Studiis et Litteris 21

I think it is important to distinguish between models for transmission and reception of the Homeric epics, even if they overlap to a significant extent. The former is about what we can say about where our physical texts came from; the latter is about how versions of the epics have been used by audiences over the years.

The main thing I want to emphasize here–and which I will elaborate on more in a later post–is that for most of the history of the transmission of the Homeric epics only a small percentage of people would have read them from beginning to end as we do today. Ancient performances would have been more frequently episodic (that is, performance of specific parts or scenes). Even in the case of monumental performances, audience engagement over several days would be effectively episodic as people tuned in and out of the performance.

The more I think about the evidence we have for the use of Homer in antiquity, I convince myself that a majority of Hellenistic through Byzantine era readers were primarily engaging with excerpts and passages for rhetorical training rather than reading through the whole beginning to end (with the exception of editors and scholars who dedicated their lives to thinking about the whole).

So, when I think of what people have done with these objects over time, I split them into post-performance era stages of reception

Panhellenic Authority

Hellenistic/Greco-Roman Authority/Literary Model

Renaissance Model/Authority

Modern Canon

Each of these periods has different assumptions about what the Homeric epics do in the world and in response prompt different questions from the epics on the part of interpreters. Not to be lost in this periodization is the implication that as early as Aristotle (if not a century before that), the Homeric epics as cultural objects do something different for the communities that praised them than they did during their first singing(s). So, when we talk about the Homeric epics, I think it is useful to acknowledge that nearly every interpretive engagement is anachronistic. We should not forbid this, but instead be careful to identify the layers of historical notions piled upon them.

In addition, I think if we look at the stages of transmission and reception together, one really important detail to consider is whether audiences were engaging with the Greek as ‘native’ speakers or learners and when they were working only with translation. This likely changed over time, but my sense is that most people who engaged with Homer in antiquity were reading it as a learned dialect, either an extension of their native Greek or as part of a language learned during their education. Translations like those of Livius Andronicus’ Odyssey were literary events of their own and should be treated that way.

With the Renaissance, I think we can safely say that most Western European encounters with Homer were with passages or translations (Petrarch famously mentions putting Homer into Latin). Whole there were certainly excellent scholars in every nation who read Homer in Greek, I think the story of Homer in the modern canonization is of an idea in translation.

Next Up: Reading and Teaching Homer: Strategies and Themes

Some things cited/Some things to read.

Bachvarova, Mary R. 2016. From Hittite to Homer: The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dué, Casey. 2018. Achilles Unbound: Multiformity and Tradition in the Homeric Epics. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Foley, J. M. 1988. The Theory of Oral Composition: History and Methodology. Bloomington.

———. 1999. Homer’s Traditional Art. Philadelphia.

———. 2002. How to Read an Oral Poem. Urbana.

González, José M. 2013. The Epic Rhapsode and His Craft: Homeric Performance in a Diachronic Perspective. Washington, D.C.: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Graziosi, Barbara. 2002. Inventing Homer. Cambridge.

Graziosi, Barbara, and Johannes Haubold. 2005. Homer: The Resonance of Epic. London: Duckworth.

Jensen, M.S. 2011. Writing Homer: A Study Based on Results from Modern Fieldwork. Copenhagen.

Lord, Albert. 2000. The Singer of Tales. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nagy, Gregory. 2004. Homer’s Text and Language. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Nagy, Gregory. 2009: Homer the Preclassic.

Ong, Walter J. 2012. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. 3rd ed. London: Routledge

Parry, Milman. 1971. The Making of Homeric Verse: The Collected Papers of Milman Parry. Edited by Adam Parry. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Ready, Jonathan. 2011. Character, Narrator and Simile in the Iliad. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ready, Jonathan. 2019. Orality, Textuality, and the Homeric Epics. 2019.

Scodel, Ruth. 2002. Listening to Homer: Tradition, Narrative, and Audience. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

West, M.L. 1997. The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

———. 2001. Studies in the Text and Transmission of the Iliad. Munich: De Gruyter.

———. 2011. The Making of the Iliad. Oxford.

———. 2014. The Making of the Odyssey. Oxford.

Whitman, Cedric H. 1958. Homer and the Heroic Tradition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wolf, F.A. 1795. Prolegomena Ad Homerum. Edited by Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most, and James E.G. Zetzel. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

The answer to questions 1 - 98 is, "Yes and no." Can't help with 99.

Excellent piece.