This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations. Don’t forget about Storylife: On Epic, Narrative, and Living Things. Here is its amazon page. here is the link to the company doing the audiobook and here is the press page. I am happy to talk about this book in person or over zoom.

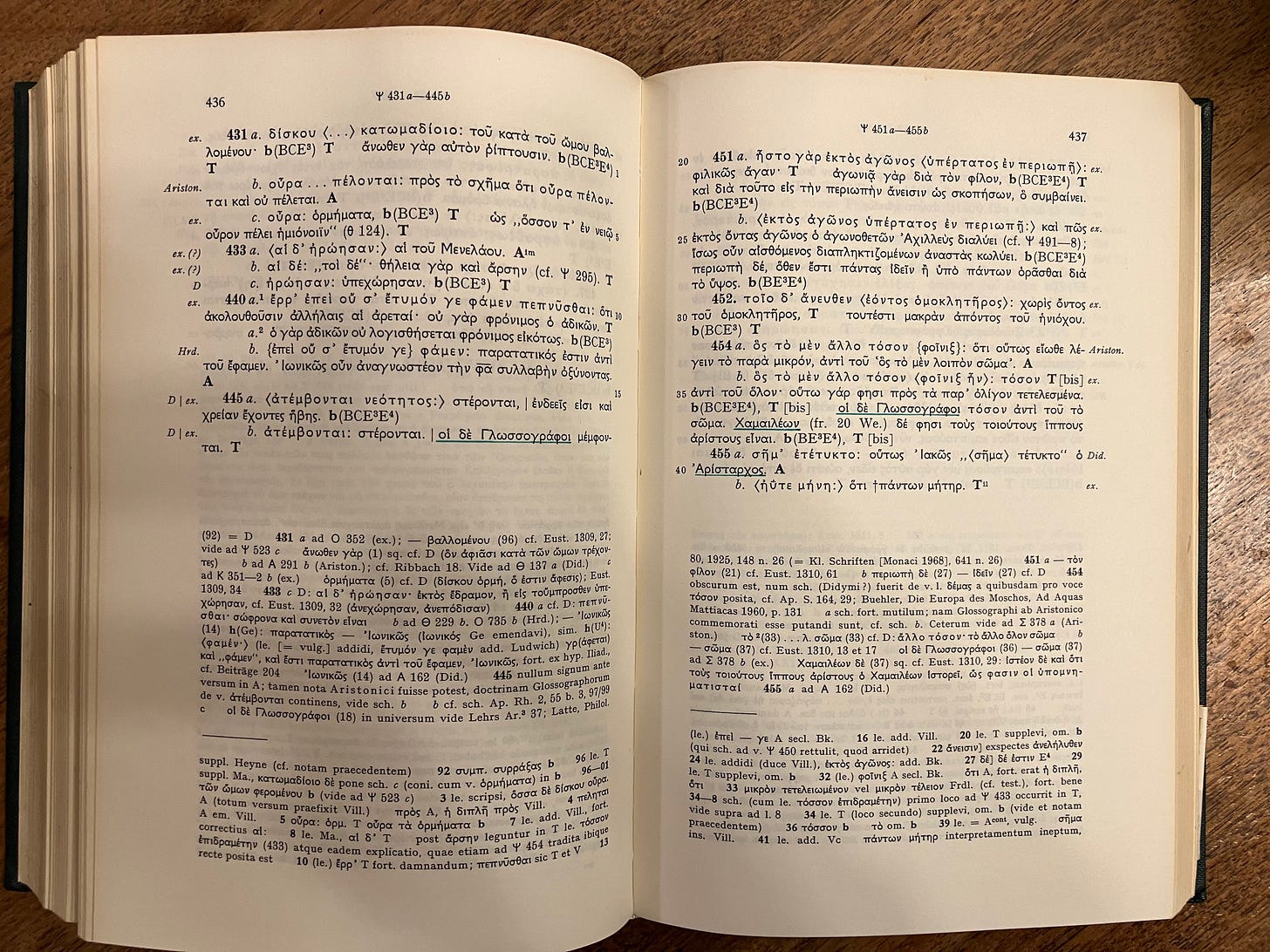

Most of the time when I am working the Iliad or Odyssey in Greek I read them side-by-side with the Homeric Scholia, usually in a digital window that looks something like this:

This is a screenshot of a rather old program called Musaios which relies on a version of the TLG_E (a CD-ROM) to provide data. It is searchable, but a bit clunky and has no updated texts. The editions that are part of it are those that were edited and published in print (the Erbse edition of the Scholia and the Allen text of the Iliad above).

Often I mention or cite the scholia on substack, but I don’t believe I have defined the term or explain why they matter. Let me correct that now! Scholia are notes added to manuscripts. They can come in margins, in between lines of the text, all over the place. Most modern readers have access to them through digital editions or print editions that are edited to look like this:

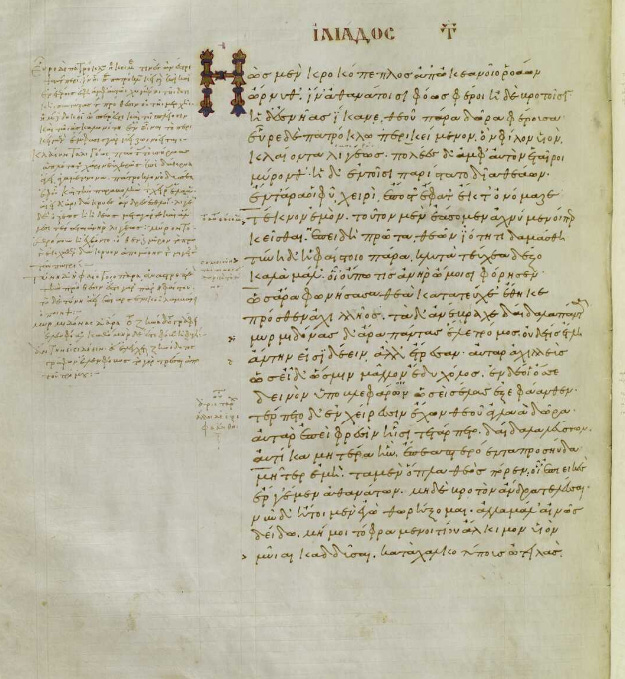

But the scholia themselves are actually edited into shared volumes from multiple manuscripts that share different textual traditions. Scholars who edit volumes of scholia consult manuscripts and make choices about what should be included in them (which means that it is possible for a lot to be left out). Here is a page from the Homeric multitext project showing the beginning of book 19 (also above). Note, there are two sets of marginal notes (one in paragraph, another connected to individual signs like footnotes) as well as intralinear notes. The marginal paragraph gives the impression of being part of a editorial tradition that likely precedes this Byzantine manuscript, while the smaller marginal notes and the intralinear seem more temporally local to that period (or later use).

No single manuscript tradition has identical scholia with others. So, when an edition is printed and ends up digitized, it can often contain very different information. The Hartmut Erbse edition (shown above) was published from 1969 to 1988 and includes a smaller proportion of what is referred to as the D Scholia many would like to see but includes far more manuscripts than the previous edition edited by Dindorf (for more, read Stephanie West’s review.) To address Erbse’s downplaying of the D Scholia, we have Helmut Van Thiel’s free edition.

The scholia contain a range of information that is generally split into two categories: minora and maiora. The minora tend to be a collection of notes to make it easier at translating Homeric Greek into later dialects, but they also include mythographical information (some ascribed to the scholar Didymus, hence the name the D Scholia). The maiora exist in most medieval manuscripts and draw on a wide range of ancient scholars writing about Homer from the Hellenistic period onward (most of which is preserved only in the scholia.

(There is a lot more detail here about the four man commentary, the VMK, and the preservation of materials from early editors like Aristarchus, Zenodotus, Aristophanes of Byzantium, scholars like Heraclitus and Porphyry, and more. Read Schironi’s overview if you want to know more!)

I have been thinking about the scholia because of this passage from book 19:

Homer, Iliad 19.4-20

“[Thetis] found her dear son lying over Patroklos

Weeping clearly. His many companions were mourning

Around him. The shining goddess stood among them—

She took his hand, named him, and spoke these words:

“My child, let’s leave him there, even though we’re in pain

Since he was doomed by the will of the gods foremost.

You now, take these famous arms from Hephaestus,

beautiful, the kinds of weapons no man has worn on his shoulders.”So speaking, the goddess put the weapons down

In front of Achilles. Those marvelous arms rang out—

Fear overtook all of the myrmidons, and no one dared

To look straight at it, no, they trembled. But Achilles,

When he saw them, well anger came over him more.

His two eyes shined out from beneath his brows like a flame

He took pleasure holding the shining gifts of the god in his hand.

But when he had taken pleasure in his thoughts as a looked at them….”εὗρε δὲ Πατρόκλῳ περικείμενον ὃν φίλον υἱὸν

κλαίοντα λιγέως· πολέες δ’ ἀμφ’ αὐτὸν ἑταῖροι

μύρονθ’· ἣ δ’ ἐν τοῖσι παρίστατο δῖα θεάων,

ἔν τ’ ἄρα οἱ φῦ χειρὶ ἔπος τ’ ἔφατ’ ἔκ τ’ ὀνόμαζε·

τέκνον ἐμὸν τοῦτον μὲν ἐάσομεν ἀχνύμενοί περ

κεῖσθαι, ἐπεὶ δὴ πρῶτα θεῶν ἰότητι δαμάσθη·

τύνη δ’ ῾Ηφαίστοιο πάρα κλυτὰ τεύχεα δέξο

καλὰ μάλ’, οἷ’ οὔ πώ τις ἀνὴρ ὤμοισι φόρησεν.

Ως ἄρα φωνήσασα θεὰ κατὰ τεύχε’ ἔθηκε

πρόσθεν ᾿Αχιλλῆος· τὰ δ’ ἀνέβραχε δαίδαλα πάντα.

Μυρμιδόνας δ’ ἄρα πάντας ἕλε τρόμος, οὐδέ τις ἔτλη

ἄντην εἰσιδέειν, ἀλλ’ ἔτρεσαν. αὐτὰρ ᾿Αχιλλεὺς

ὡς εἶδ’, ὥς μιν μᾶλλον ἔδυ χόλος, ἐν δέ οἱ ὄσσε

δεινὸν ὑπὸ βλεφάρων ὡς εἰ σέλας ἐξεφάανθεν·

τέρπετο δ’ ἐν χείρεσσιν ἔχων θεοῦ ἀγλαὰ δῶρα.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ φρεσὶν ᾗσι τετάρπετο δαίδαλα λεύσσων

I find this passage fascinating for a few reasons. First, a simple observation: there’s nearly a grammatical anakolouthon as the narrative attempts to describe Achilles’ response. It starts with a typical shifting device from one subject to another, “But then Achilles” (αὐτὰρ ᾿Αχιλλεὺς), when he saw it, because anger overtook him more, his eyes…” The narrative begins with the whole person, but then shifts from him as a grammatical subject, to the object of kholos (‘anger’), to the terrible glint in his eyes.

That line is filled with movement: ὡς εἶδ', ὥς μιν μᾶλλον ἔδυ χόλος, ἐν δέ οἱ ὄσσε has three different grammatical subjects (Achilles, the anger, the eyes) but all of them are different ways of seeing Achilles: first as a narrative subject, then as an object of anger, and then the impact of the anger through the glint in his eyes. The transition from here is surprising too: Achilles feels pleasure in the weapons. One of the last times the audience was asked to think about Achilles feeling pleasure was when the embassy came to him in book nine (τὸν δ' εὗρον φρένα τερπόμενον φόρμιγγι λιγείῃ, 9,186). There, he was with Patroklos, but still separate, alone in feeling pleasure at the lyre. Here, he moves from mourning, to anger, to pleasure at the weapons that terrify his men.

The second thing that really interests me about this passage is the difference between Achilles’ reaction to the weapons and that of the Myrmidons. While Achilles feels delight, his men are overcome by fear and cannot look at the arms (Μυρμιδόνας δ' ἄρα πάντας ἕλε τρόμος, οὐδέ τις ἔτλη / ἄντην εἰσιδέειν, ἀλλ' ἔτρεσαν, Schol. B ad Il. 19.15). And here’s where the scholia come in. Zenodotus quibbles and thinks the word should be “rout” (φόβος) instead of “trembling” (τρόμος). (In one of the many places where Zenodotus is wrong, he makes this assertion but does not seem to correct the coordinate verb ἔτρεσαν which creates a nice repetition and ring in a very Homeric fashion).

The b Scholion for this passage explains that “The Myrmidons are awestruck by the beauty, but they can’t look at it.” (οἱ δὲ Μυρμιδόνες τὸ κάλλος ἐκπλήττονται, ἀντοφθαλμεῖν μὴ δυνάμενοι). I think that this interpretation is bonkers, personally. The language used by the narrator makes it very clear that weapons have a martial menace: the language of trembling in fear is what happens when warriors are about to run away, when they face a challenge they would rather avoid. There is a divine force imbued in the weapons that makes the Myrmidons tremble.

The contrast in reactions is a powerful reminder of the affective force of wrought objects. Hephaestus’ weapons inspire different reactions in different viewers because they mean different things. To the Myrmidons, they are a return to war, a return to the field where they just lost Patroklos. To Achilles, they are a means to fulfilling his rage. And, if we accept that the Shield itself as an ekphrasis is a representation of poetic art, of narrative’s power, this moment helps us understand that Homer knows that creative art has different effects on different people.

Other posts on Iliad 19

People Are Going to Tell Our Story: Introducing Iliad 19: Paradeigmata, again; cognitive approaches to reading, again; Achilles and Agamemnon; Politics

That Other Me: Achilles' Lament for Patroklos in Iliad 19: Achilles and Patroklos, again; Achilles’ Second Lament; Surrogacy; Cognitive approaches to reading, again; Briseis

Dead and Gentle Forever: Briseis' Lament for Patroklos in Iliad 19: Briseis; Laments; Scholia; Patroklos

Francesca Schironi has a good overview of the Homeric Scholia here (from the Cambridge Guide to Homer).

Helmut van Thiel’s edition of the D. Scholia: a clean and easy to read FREE pdf with far more of the D Scholia than are included in the TLG. Dindorff’s Scholia to the Iliad can also be downloaded

The best guide to the scholia is Eleanor Dickey, Ancient Greek Scholarship: a guide to finding, reading, and understanding scholia, commentaries, lexica, and grammatical treatises, from their beginnings to the Byzantine period. London and New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

A few more suggestions from Justin Arft:

Schironi, F. 2018. The Best of the Grammarians: Aristarchus of Samothrace on the Iliad. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Schironi digs deep into the Homeric scholia to contextualize Aristarchus' editorial style and goals. Exhaustive examples from the Iliad in particular (some from the Odyssey when appropriate) to determine his views on grammar, style, narrative, and especially his attitude toward other critics.

Nünlist, R. 2009. The Ancient Critic at Work: Terms and Concepts of Literary Criticism in Greek Scholia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nünlist is more broadly focused on scholiasts writ large (across genres and authors) but spends a good amount of time on Aristarchus and Homeric speech, from epithets, type-scenes, narrative, and character, too. From the Intro: "The book is divided into two parts . The first part ( Chapters 1 to 12 ) deals with the more general concepts of literary criticism which ancient scholars recognised in various texts and did not a priori consider typical of a particular poet or genre . For the sequence of the chapters in this first part , an attempt has been made to proceed from the more general to the more specific ( but to keep thematically related chapters together ) . The second part deals with literary devices that were primarily seen as typical of a particular poet ( Homer , Chapters 13 to 18 ) or genre ( drama , Chapter 19 )."