This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 17. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

One of the things I emphasized in my first post on Iliad 17 is the book’s overlapping functions. On the one hand, it creates narrative suspense by forestalling the news of Patroklos getting to Achilles for one more book (therefore delaying the transfer of Achilles’ rage from the Achaeans to Hektor). On the other hand, it still carries out some essential characterization to help to frame the actions that follow. In a way, I think books 16 and 17 are really part of the same narrative unit: together they are something like an extended director’s cut.

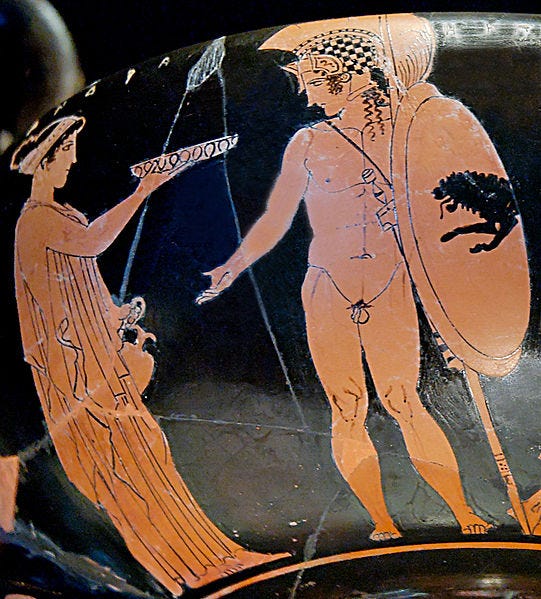

The latter quarter of book 16 and the first half of book 17 center around the characterization of Hektor. There is something of an interlocking structure too: following the death of Sarpedon, Hektor moves closer to Patroklos, only to have Euphorbus appear to wound him, and then once Patroklos dies, Menelaos swiftly dispenses with Euphorbus and the focus falls again on Hektor. Glaukos, the second best of the Lykians, tears into Hektor:

Homer, Iliad 17.141-168

“Then Glaukos, the child of Hippolochus and leader of the Lykian men

Tore into Hektor in speech as he glared at him:

‘Hektor, best in form, you really have lacked much when it comes to war.

Truly, a fine fame holds you thus as a coward.

Consider now how you will save the city and the town

alone with only the host born in Troy at your side,

for none of the Lykians at least will go around the city

to battle the Danaans, since there really is no thanks

for men to struggle endlessly forever against the enemy.’

How could you save a lesser man in the roiling battle,

Fool, when you abandoned your friend and companion Sarpedon

As spoil and a trophy for the Argives?

We was a great boon to you and your city when he was alive!

But now you don’t even dare to protect him from the dogs.

So now if any of the Lykians will obey me to go home,

It will mean an awful destruction for Troy.

But if there were a real boldness in Trojan hearts,

An unwavering force, the kind that enters men when

They face toil and strife against the enemy for their homeland,

Then we could quickly take Patroklos into Troy.

If that man arrives dead in the great city of lord Priam,

And we safeguard him from battle rage,

Then the Argives will release the fine weapons of Sarpedon

And we can take him back to Troy.

For the attendant who died belongs to the kind of man who is

The best of the Argives among the ships, along with those close-fighting henchmen.

But you don’t dare to face great-hearted Ajax,

To look him in the eyes in the roar of the battle,

Nor to go straight to fight him, since he is better then you.”

A student recently asked me to try to make sense of who the best fighters are in the Iliad. Among the Trojans and their allies, there are three of pedigree and reputation to be reckoned with: Hektor, Aeneas, and Sarpedon. One of the interesting things about the primary Trojan warriors, however, is how their performance doesn’t quite seem to match up to expectations. Aeneas has to be rescued twice in battle. Sarpedon struggles against Tlepolemus, a minor son of Herakles, and then falls before Patroklos. Hektor can generously be said to match up with Ajax in the duel of Iliad 7, but seems to repeatedly fail to live up to his billing as “man-slaying Hektor” in major battles. Note the use of the word “seems” here: according to Peter Gainsford’s chart on named kills in the Iliad, Hektor is the epic leader in slaughter.

(Note, Aeneas is the next highest ranked Trojan and Sapedon isn’t even on the list)

But I fear that we need to view this as a ‘regular’ season award with an asterix. What would Hektor’s kill rate look like without Achilles sitting out more than half the epic? What do gaudy statistics mean if you end up losing in the long run? Is Hektor more or less than a Homeric Dan Marino?

By book 17 in the epic, Hektor has led the Trojans through 10 books of steady advance, stymied by divine intervention in book 14 and Patroklos’ return in book 16. But any careful reading of the epic will note that despite all of Hektor’s prowess, the Trojan success is due to Zeus’ interference: hurling lightning bolts in book 8, pulling other gods out of the fray in book 15, and foretelling Patroklos’ death as well. Book 17 is one of those ‘evenly matched’ battle scenes where the drama comes less from the blood spilled than from the words spoken. And these words can take us back to some of Trojan problems.

Glaukos criticizes Hektor the way Hektor insults his brother Paris in book 7: he maligns him for being handsome and equates that beauty with uselessness in war (sorry, Achilles). His language and overall tone reflect his earlier speech after Sarpedon falls (16.538-47) and Sarpedon’s speech in book 5 where the Lykian leader criticizes Hektor’s martial prowess and his ability to lead (5.472-492). Where Sarpedon reminds Hektor of the military importance of the allies, Glaukos threatens to withdraw altogether. After suggesting that they win Patroklos’ body in order to exchange it for Sarpedon’s, Glaukos ends by insulting Hektor again, implying that he is not bold enough to face Ajax (167-8).

As I have written about before, speeches like this echo and reinforce a generally critical view of Trojan politics as being self-interested (to the royal family) and unresponsive (to everyone else). Hektor’s interest in book 8 takes him running after new horses, here he is led to grab new armor. In a way, Glaukos’ remonstration should be seen as a desperate attempt to get Hektor to engage and pay attention. Hektor responds by dismissing Glaukos’ ability to think and then repeats the motif of uncertainty in war, noting that “Zeus’ mind can rout even a brave man”. And yet, despite his objections, Zeus seems to take Glaukos’ criticism to heart: he enjoins him (17.179-82):

‘Come here, friend, stand next to me and watch my work,

whether I will really be an all-day coward, as you publicly announce,

or whether I will hold back some one of the Danaans

even one rushing full of valor to defend dead Patroklos.’

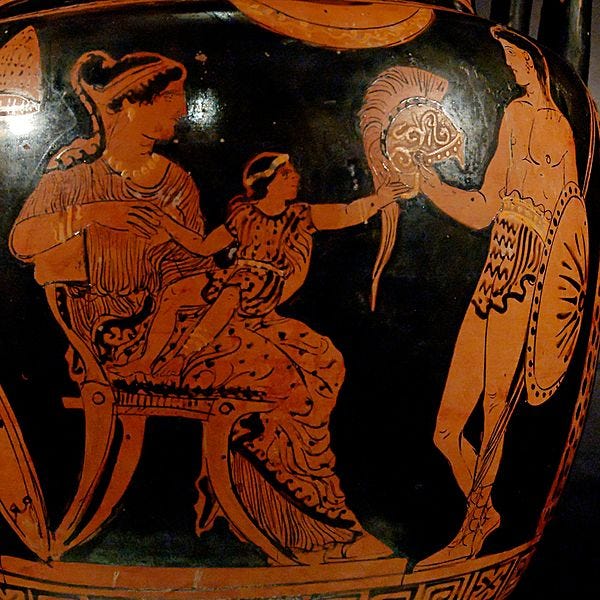

Hektor doesn’t really engage with Glaukos’ plan, just as he ignores advice from Polydamas earlier and Andormache in book 17. Hektor here is more like a school yard bully responding to a dare. In his response, he says nothing about Sarpedon’s body. I think that Hektor hears what he wants to in Glaukos’ speech and then rejects or ignores everything that doesn’t adhere to his current worldview. Hektor leaves from this exchange and is depicted trying to rally his allies (17.215-19). He promises to share the spoils and fame with whoever aids him in seizing Patroklos’ body, but the narrator apostrophizes them as fools. And this narrative dismissal comes after one of the more memorable scenes in the book. As Hektor picks up Achilles’ weapons and dons them, Zeus shakes his head in pity (201-208):

“Ah, wretched one, you’re not thinking of death at all,

And it is certainly near you. You’re putting on the weapons

Of the best man, one everyone else is afraid of!

You killed his noble and strong friend,

But you’ve pulled the arms off his shoulders and head

Against good order. Well, I’ll give you great strength now

But the payback for this is that there’s no way that Andromache

Will take Achilles’ weapons from you when you have returned from war”

Zeus’ pity for Hektor and his judgment here are likely internal guides for how the audience should be reading Hektor. Hektor is by far the best the Trojans have to offer but he is without a doubt not enough to save the city and never was going to be. The word used in this speech poinê (payback) is used in expressing payback or exchange, generally for offenses, the crime of abducting Helen or things like murdered children. Zeus’ language implies that Hektor has committed some kind of a transgression, but to whom is the debt owed?

The Iliad explores thematic explanations for why this might be the case. Since leaving the city and enjoying temporary success, Hektor has reached beyond any other point in the conflict and, as most ‘heroes’ do, he goes too far. His exchange with Glaukos helps to indicate how desperately he hears only what he wants to hear and Zeus’ speech puts a cap on the whole affair. By mentioning Andromache, Zeus puts the cost of Hektor’s loss in perspective.

And, yet, the epic’s rhetoric here seems a little uncertain, if not unfair. Hektor was always going to lose. Nothing he could do would accomplish much more than postponing the city’s eventual destruction. What is the impact of characterizing him as a wretch and those who follow him as fools? In a way, Hektor’s overreaching is paired with Patroklos’ in book 16 and is also an instantiation of the ‘double motivation’ I have mentioned earlier. The Iliad wants to combine human agency and divine will. It is not enough for human beings to suffer because of divine vacillation: for human life to have meaning, it must come with some choice. The question isn’t what happens to you in the end, it is how you comport yourself along the way.

Hektor’s actions in book 17 help to prepare us for further extremes: when he refuses to retreat again in book 18 and then, finally, when he stands alone to face Achilles in book 22 and runs away. The tension between what we expect from Hektor and what he accomplishes forces us as an audience to come up with explanations, causes. Ass I will write about in talking about book 22, I think Hektor’s characterization evokes the long term effect of trauma. But that’s my take: Hektor develops through the Iliad as an enigma. He may be less mysterious or infuriating than Achilles, but he remains a question audiences labor to answer.

In the end, we are probably like Zeus, shaking our heads and murmuring a lament for Hektor, the star warrior who never wins the big one.

A short Bibliography on book 17

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Barker, Elton T. E., and Joel P. Christensen. 2019. Homer's Thebes: Epic Rivalries and the Appropriation of Mythical Pasts. Hellenic Studies Series 84. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Degener, Michael. “Euphorbus’ plaint and plaits: the unsung valor of a foot soldier in Homer’s « Iliad ».” Phoenix, vol. 74, no. 3-4, 2020, pp. 220-243. Doi: 10.1353/phx.2020.0037

Fenno, Jonathan Brian. “The mist shed by Zeus in Iliad XVII.” The Classical Journal, vol. 104, no. 1, 2008-2009, pp. 1-9.

Harrison, E. L. “Homeric Wonder-Horses.” Hermes 119, no. 2 (1991): 252–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4476820.

Kozak, Lynn. “Character and context in the rebuke exchange of Iliad 17.142-184.” Classical World, vol. 106, no. 1, 2012-2013, pp. 1-14.

Moulton, C.. “The speech of Glaukos in Iliad 17.” Hermes, vol. CIX, 1981, pp. 1-8.

Neal, Tamara. “Blood and hunger in the « Iliad ».” Classical Philology, vol. 101, no. 1, 2006, pp. 15-33. Doi: 10.1086/505669

Schein, Seth L.. “The horses of Achilles in Book 17 of the « Iliad ».” « Epea pteroenta »: Beiträge zur Homerforschung : Festschrift für Wolfgang Kullmann zum 75. Geburtstag. Eds. Reichel, Michael and Rengakos, Antonios. Stuttgart: Steiner, 2002. 193-205.

West, M. L. “‘Iliad’ and ‘Aethiopis.’” The Classical Quarterly 53, no. 1 (2003): 1–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3556478.