This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations. Don’t forget about Storylife: On Epic, Narrative, and Living Things. Here is its amazon page. here is the link to the company doing the audiobook and here is the press page. I am happy to talk about this book in person or over zoom.

As I write in the first post on book 15, action of the book is split into two basic movements: Zeus’ conversations with the gods to threaten or cajole them and the resulting actions taken to rally the Achaeans. The book is in part about resetting the disorder introduced in book 15 and preparing us to return to the main plot of the Iliad: Achilles’ anger and the conflict between the Achaeans and the Trojans.

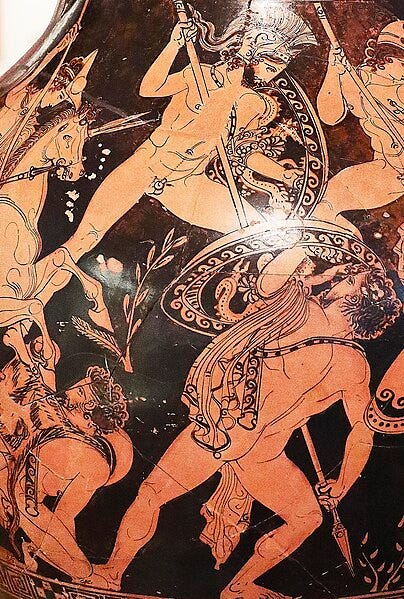

The process is not as simple as I imply in that earlier post. Hera doesn’t simply accept Zeus’ return and reversal of events. After the other gods have been upbraided, she makes sure that Ares learns about the death of his own son, Askalaphos.

Iliad 15.113-122

“I expect right now that Ares, at least, is feeling some pain:

For his son, the dearest of men, died in battle—

Askalaphos, the one strong Ares claimed as his own”

So she spoke, and Ares pounded on his powerful thighs,

Working his hands into them, and he spoke a word in mourning.

“Don’t you criticize me, all of you who have Olympian homes,

Because I pay back the murder of my son who went among the ships of the Achaeans,

Even if it is my fate too to be struck by Zeus’ lightning

And to lie there in the blood and dust among the corpses.”

So he spoke, and he called for his horses Fear and Rout

To be yoked and he put on his shining armor himself

Then there would have been another harsh anger [kholos]

And rage among the immortals from Zeus and rage [mênis] too…”ἤδη γὰρ νῦν ἔλπομ’ ῎Αρηΐ γε πῆμα τετύχθαι·

υἱὸς γάρ οἱ ὄλωλε μάχῃ ἔνι φίλτατος ἀνδρῶν

᾿Ασκάλαφος, τόν φησιν ὃν ἔμμεναι ὄβριμος ῎Αρης.

῝Ως ἔφατ’, αὐτὰρ ῎Αρης θαλερὼ πεπλήγετο μηρὼ

χερσὶ καταπρηνέσσ’, ὀλοφυρόμενος δ’ ἔπος ηὔδα·

μὴ νῦν μοι νεμεσήσετ’ ᾿Ολύμπια δώματ’ ἔχοντες

τίσασθαι φόνον υἷος ἰόντ’ ἐπὶ νῆας ᾿Αχαιῶν,

εἴ πέρ μοι καὶ μοῖρα Διὸς πληγέντι κεραυνῷ

κεῖσθαι ὁμοῦ νεκύεσσι μεθ’ αἵματι καὶ κονίῃσιν.

῝Ως φάτο, καί ῥ’ ἵππους κέλετο Δεῖμόν τε Φόβον τε

ζευγνύμεν, αὐτὸς δ’ ἔντε’ ἐδύσετο παμφανόωντα.

ἔνθά κ’ ἔτι μείζων τε καὶ ἀργαλεώτερος ἄλλος

πὰρ Διὸς ἀθανάτοισι χόλος καὶ μῆνις ἐτύχθη,

Hera really ‘tweaks’ Ares a bit here by dropping the information in this way and, perhaps, by casting some doubt on the parentage. It works because Ares gets upset and gets ready to go to war. What really stands out for me in this passage is the contrafactual that anticipates two kinds of anger

A scholion reports that these words are “parallel and possessing the same meaning” (Ariston. <χόλος καὶ μῆνις:> ὅτι ἐκ παραλλήλου ὡς ἰσοδυναμοῦντα τὸν χόλον καὶ τὴν μῆνιν.) The doublet (and the passage) reminds me of the alternate version of the proem of the Iliad

“Tell me now Muses who have Olympian homes

How in fact rage and anger overtook Peleus’ son

And the shining son of Leto…for he was angry at the king”ἕσπετε νῦν μοι Μοῦσαι ᾿Ολύμπια δώματ’ ἔχουσαι,

ὅππως δὴ μῆνίς τε χόλος τ’ ἕλε Πηλεΐωνα

Λητοῦς τ’ ἀγλαὸν υἱόν· ὃ γὰρ βασιλῆϊ χολωθεὶς

As Lenny Muellner shows in his book, mênis is marked as divine anger over a cosmic rupture. For Achilles in the Iliad, mênis indicates that his anger is super-charged (because he is semi-divine) and also emerging from a breakdown in social/political organization equivalent to a transgression against the basic assumptions of individual rights and place in the community.

In the alternate proem we can imagine the doublet as characterizing both Achilles’ and Apollo’s responses to the events of Iliad 1: the social anger of kholos describes the onset of anger from the breakdown of expected practices, while mênis conveys Apollo’s rage over the dishonoring of his priest as well since the rights and honors given to the gods are part of the stability of the Olympian realm. Thomas Walsh has argued that kholos indicates anger that is socially motivated, generally among peers. In book 1 of the Iliad, according to Achilles, kholos overtakes Agamemnon (1.387) because Achilles took action and called for them to propitiate the god in response to the plague. In the combining of the two, I suggest we see both a complementary pair (one is universal and capacious, the other is local and capricious) but also a doublet that anticipates compounding outcomes.

Let me try to explain this through doublet in book 15 and the doublet that appears in the alternative proem: they suggest that there are different kinds of anger and that they have different consequences. The initial kholos may indicate the conflict itself, the manifestation of anger that is violence. The subsequent mênis is an anticipation based on who is part of the conflict. Were Ares to challenge Zeus, it would have cosmic implications: the death of Ares would disrupt the distribution of goods and rights among the gods and promise future conflict (especially between Zeus and Hera). I think there is some confirmation here of the difference implied by Athena’s intervention. She rushes down from Olympus and warns Ares not to engage in this destructive behavior. When she asks him directly to put his anger down, she says “I am thus asking you now to put aside the kholos over your son” (τώ σ' αὖ νῦν κέλομαι μεθέμεν χόλον υἷος ἑῆος, 15.138). The kholos-anger here is over the loss of a mortal child, whose presence or absence from the divine perspective cannot have cosmic relevance unless Ares challenges his father (or the other gods) over it.

As I have explored before, the Iliad presents some shared language between Ares and Achilles. When Ares challenges Zeus in book 5 and Zeus dismisses him there are echoes that could lead some audience members to imagine Ares as Achilles and Agamemnon as Zeus. The parallels are incomplete and jagged, to an extent, but the cast each conflict as one that has the potential to destroy the communities that depend upon their kings and leading warriors. But in each case, there is the chance that anger (kholos) can slide into a paradigm shifting/shattering rage (mênis) if the players do not understand the stakes of their own stories.

Other Posts on Iliad 15

1. Zeus and 'Righting' the Divine Constitution: An Introduction to Reading Iliad 15: Divine Politics and Homeric Gods; Hesiod’s Theogony

2. Brothers, Sisters, Wives, and Divine (Dis)Order: Setting things Straight in Iliad 15: Homeric gods; Zeus and Poseidon; Successions; Politics

3. The Powerful Mind of Zeus: Revitalizing Hektor and the Iliad's Plot: Hektor, Zeus, and the Plot of the Iliad

A (way too) Short bibliography

Christensen, Joel P. 2012. “Ares: ἀΐδηλος: On the Text of Iliad 5.757 and 5.872.” Classical Philology 107.3, 230-238.

Muellner, Leonard. 1996. The Anger of Achilles: Mênis in Greek Epic. Cornell.

Walsh, Thomas. Feuding Words, Fighting Words: Anger in the Homeric Poems. Washington, D. C.: Center for Hellenic Studies. 2005

This idea of doubles connected to μῆνις is really interesting! thank you for this post!