In an earlier post on “the plan,” I promised to start with guidelines for how to read Homeric epic and I promise to do that, but I am including some random posts about the beginning of the epic to get warmed up. There will be a handful of posts about preparing for epic and then I will get started on book-specific posts, covering a book a week for the duration. If all goes according to plan, I’ll intersperse these posts with scholia, essays, and observations for each book during its week.

As I discussed in an earlier post the beginning of the Iliad contains thematically resonant language that engages with the larger poetic tradition while also informing audiences what to expect from this poem:

Hom. Iliad 1.1-8

Μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω ᾿Αχιλῆος

οὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί’ ᾿Αχαιοῖς ἄλγε’ ἔθηκε,

πολλὰς δ’ ἰφθίμους ψυχὰς ῎Αϊδι προΐαψεν

ἡρώων, αὐτοὺς δὲ ἑλώρια τεῦχε κύνεσσιν

οἰωνοῖσί τε πᾶσι, Διὸς δ’ ἐτελείετο βουλή,

ἐξ οὗ δὴ τὰ πρῶτα διαστήτην ἐρίσαντε

᾿Ατρεΐδης τε ἄναξ ἀνδρῶν καὶ δῖος ᾿Αχιλλεύς.“Goddess, sing the rage of Pelias’ son Achilles,

Destructive, how it gave the Achaeans endless pains

And sent many brave souls of heroes to Hades—

And it made them food for the dogs

And all the birds as Zeus’ plan was being fulfilled.

Start from when those two first diverged in strife,

The lord of men Atreus’ son and godly Achilles.”

A few things to note from here: this is not the story of the Trojan War. Indeed, it is only clear that it is set in the Trojan War because of the naming of the heroes Achilles and Agamemnon and the invocation of the plan of Zeus. In a way, the proemia of epic poems (the “fore-songs”, if you will) function like the chyrons at the beginning of Star Wars films, inviting audiences to situate the story to be told in some kind of narrative frame.

When I read the Iliad or the Odyssey with students, I spend an inordinate amount of time on these introductory passages because they do so much to set up the stories to come, both through what they say and leave unsaid.

But what translations often lead out is that these famous lines aren’t the only ones we have for beginning the poems. The manuscript traditions of the Iliad provide in addition to the well-known 8 line proem, a few shorter, alternate beginnings:

D Scholia ad Hom. Il. Prolegomenon in Rom. Bibl. Nat gr. 6:

“An Iliad which appears to be ancient, called Apellicon’s, has this proem

I sing of the Muses and Apollo, known for his bow...

This is recorded by Nikanôr and Crates in his Critical Notes on the Text of the Iliad. Aristoxenus in the first book of his Praxidamanteia says that some had as the first lines:

Tell me now Muses who have Olympian Homes

How rage and anger overtook Peleus’ son

And also the shining son of Leto. For the king was enraged...”

ἡ δὲ δοκοῦσα ἀρχαία ᾿Ιλιάς, λεγομένη δὲ ᾿Απελλικῶνος, προοίμιον ἔχει τοῦτο·

Μούσας ἀείδω καὶ ᾿Απόλλωνα κλυτότοξον

ὡς καὶ Νικάνωρ μέμνηται καὶ Κράτης ἐν τοῖς διορθωτικοῖς. ᾿Αριστόξενος

δ' ἐν α′ Πραξιδαμαντείων φησὶν κατά τινας ἔχειν·῎Εσπετε νῦν μοι, Μοῦσαι ᾿Ολύμπια δώματ' ἔχουσαι,

ὅππως δὴ μῆνίς τε χόλος θ' ἕλε Πηλεΐωνα,

Λητοῦς τ' ἀγλαὸν υἱόν· ὁ γὰρ βασιλῆι χολωθείς.

Obviously, these variant beginnings don't signal a different poem, but they do set up the audience in different ways. The latter variants especially point to a greater emphasis (perhaps) on Apollo. There’s much written on this, but for a start see Vince Tomasso’s comments on these beginnings as rhapsodic alternatives, Greg Nagy’s overview of the importance of Apollo’s rage at the beginning of the Iliad and Casey Dué’s comments as part of a larger discussion of multiformity.

When it comes to these lines, the question is whether they derive from a performance tradition of the story of the rage of Achilles as more or less equally likely options to begin the epic poem we currently have, or they are variants left over from traditions of other Iliads. I am generally agnostic and think that the scholars I have mentioned above all have really good arguments.

I do note here that when I use the word multiform as opposed to variant I (think) I mean a more-or-less equally possible option from the performance tradition. When I use ‘variant’, I mostly mean a less-likely or aesthetically apt alternative (because variant implies a movement from something standard or already extant). But Casey Dué’s (free!) book Achilles Unbound is far more nuanced and informative in discussing these things. I also suggest José M. González’s The Epic Rhapsode and His Craft: Homeric Performance in a Diachronic Perspective

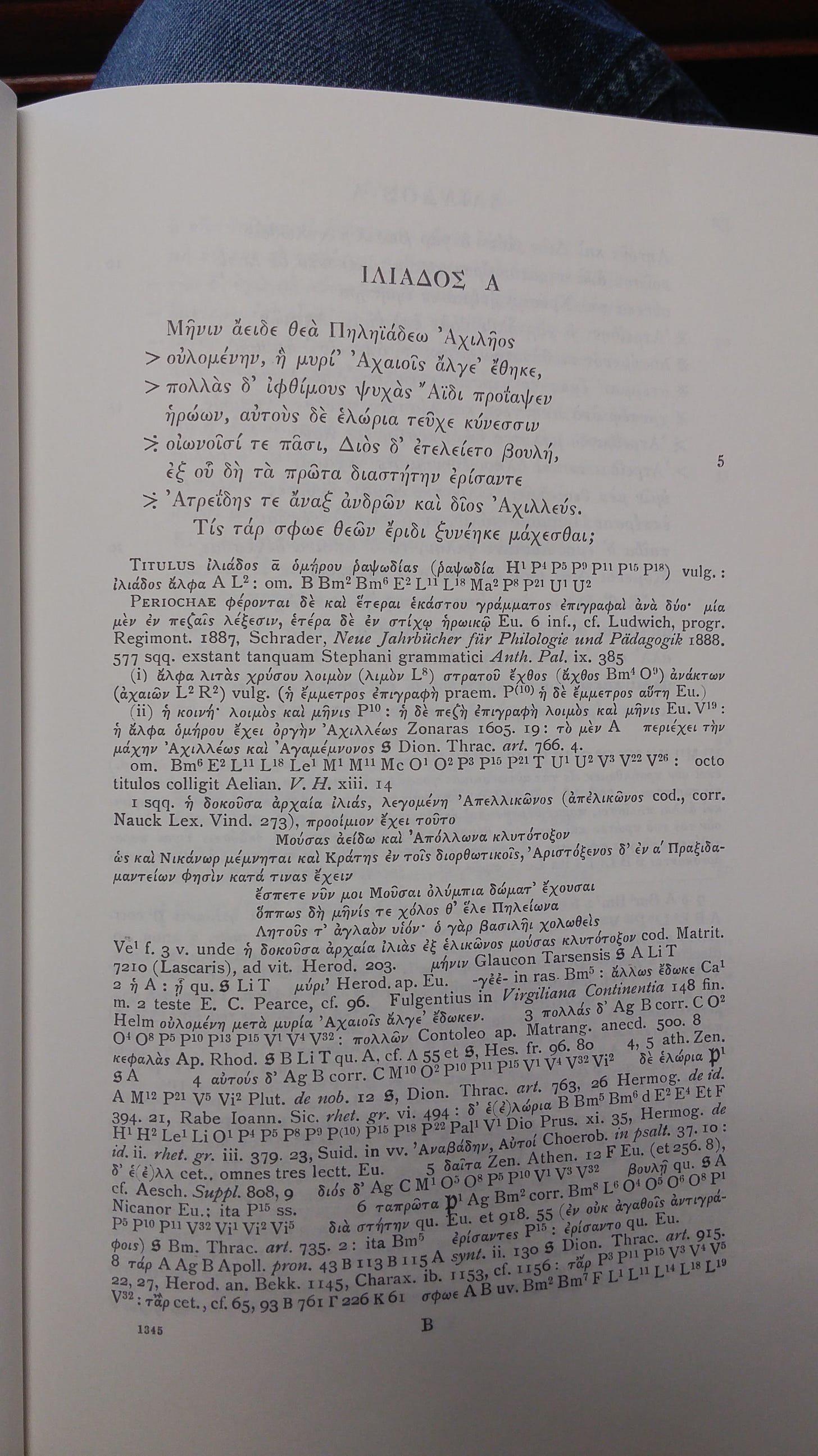

For those with access to modern editions of the Iliad, information like is crammed in the critical apparatus of Allen's edition of the Iliad (1931):

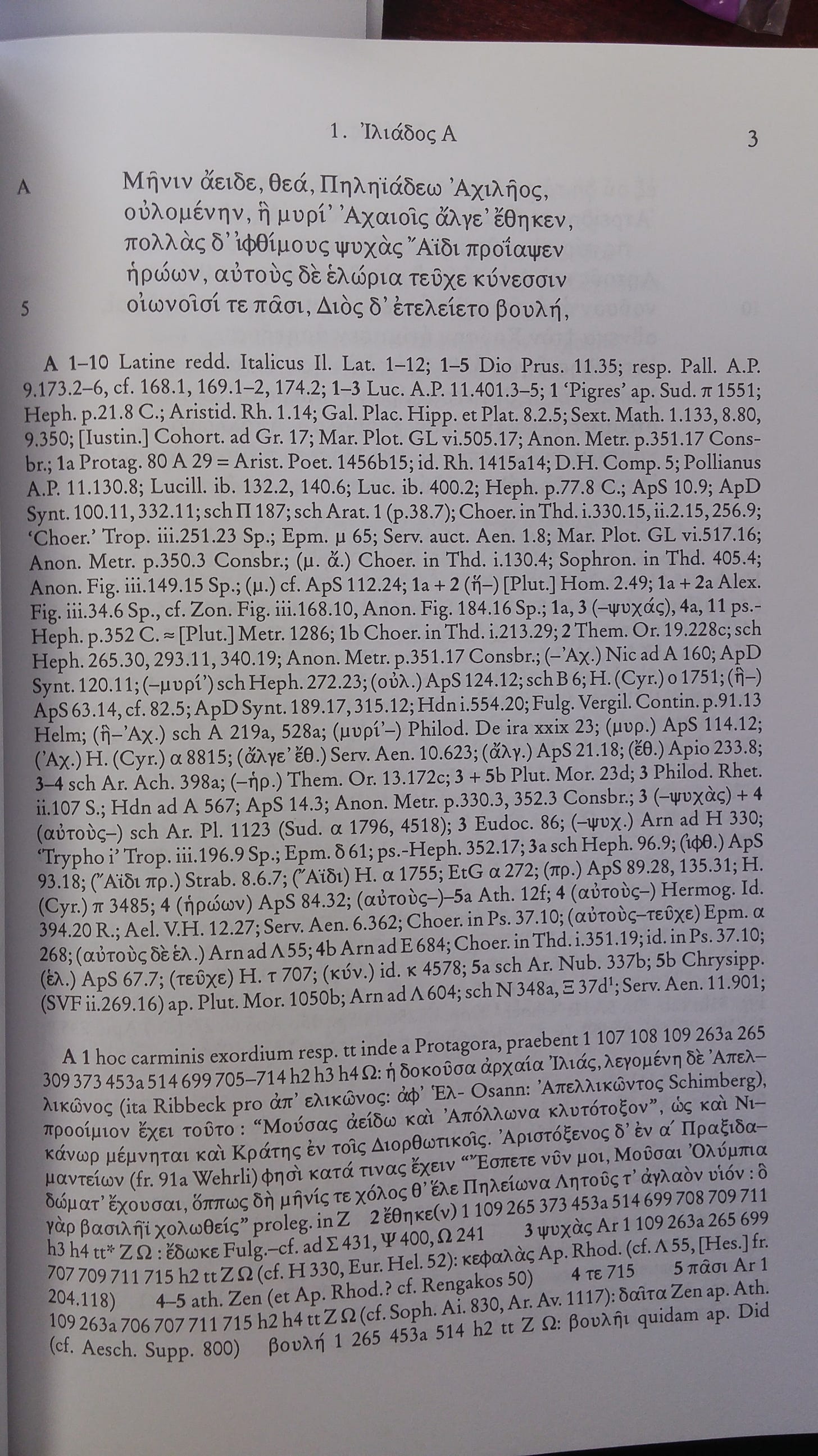

It is also to be found in West's more recent edition (1998):