This post provides some additional information for thinking about Iliad book 4, in particular references to Thebes and Tydeus. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

As Elton Barker and I emphasize in our work on Homer, we think poetic rivalry was a formative feature of the generation of epic poetry in performance over time. The culture projected within the Homeric world is deeply competitive and rivalry between the Homeric poems through the main figures Achilles and Odysseus is clear as well. But we also argue that agonism should be seen as a primary force in the way Homeric poems relate to other traditions as well, particularly those surrounding Thebes.

(See this recent video we participated in on The Story of Thebes.)

Thebes comes to the fore in book 4 when Agamemnon reviews his troops and exhorts them to battle in the so-called Epipolesis. By the time he gets to Diomedes, he leans a little more into the language of reproach and attempts to shame Diomedes by comparing him to his father.

Hom. Il. 4.387-393; 396-400

There, stranger though he was, horse-driver Tydeus was not frightened, alone among many Cadmeans. But he challenged them to contests and won victory in all easily. Such a guardian was Athena for your father! But the Cadmeans, drivers of horses, were angered and, as he departed from the city, they set up a close ambush of fifty youths; there were two leaders.... But Tydeus let loose on them a unseemly fate: he slew them all and only one man he sent to return home: he sent Maion, trusting in the signs of the gods. Such a man was Aitolian Tydeus; but he fathered a son weaker than he in battle, but better in the assembly

ἔνθ᾿ οὐδὲ ξεῖνός περ ἐὼν ἱππηλάτα Τυδεὺς

τάρβει, μοῦνος ἐὼν πολέσιν μετὰ Καδμείοισιν,

ἀλλ᾿ ὅ γ᾿ ἀεθλεύειν προκαλίζετο, πάντα δ᾿ ἐνίκα

ῥηϊδίως· τοίη οἱ ἐπίρροθος ἦεν Ἀθήνη.

οἱ δὲ χολωσάμενοι Καδμεῖοι, κέντορες ἵππων,

ἂψ ἄρ ᾿ ἀνερχομένῳ πυκινὸν λόχον εἷσαν ἄγοντες,

κούρους πεντήκοντα· δύω δ᾿ ἡγήτορες ἦσαν...

Τυδεὺς μὲν καὶ τοῖσιν ἀεικέα πότμον ἐφῆκε·

πάντας ἔπεφν᾿, ἕνα δ᾿ οἶον ἵει οἶκόν δὲ νέεσθαι·

Μαίον᾿ ἄρα προέηκε, θεῶν τεράεσσι πιθήσας.

τοῖος ἔην Τυδεὺς Αἰτώλιος· ἀλλὰ τὸν υἱὸν

γείνατο εἷο χέρεια μάχῃ, ἀγορῇ δέ τ᾿ ἀμείνω

After he does this, Sthelenos, the Patroklos to Diomedes’ Achilles, objects strongly. Asserting that he and Diomedes actually sacked a city when their fathers failed to do so.

Homer, Iliad. 4.404-110

Son of Atreus, don’t lie when you know how to speak clearly. We claim to be better than our fathers: we took the foundation of seven-gated Thebes though we led a smaller army before better walls because we were relying on the signs of the gods and Zeus’ help. Those men perished because of their own recklessness. Don’t put our fathers in the same honour’’

Ἀτρεΐδη, μὴ ψεύδε ᾿ ἐπιστάμενος σάφα εἰπεῖν·

ἡμεῖς τοι πατέρων μέγ᾿ ἀμείνονες εὐχόμεθ᾿ εἶναι·

ἡμεῖς καὶ Θήβης ἕδος εἵλομεν ἑπταπύλοιο

παυρότερον λαὸν ἀγαγόνθ᾿ ὑπὸ τεῖχος ἄρειον,

πειθόμενοι τεράεσσι θεῶν καὶ Ζηνὸς ἀρωγῇ·

κεῖνοι δὲ σφετέρῃσιν ἀτασθαλίῃσιν ὄλοντο·

τὼ μή μοι πατέρας ποθ᾿ ὁμοίῃ ἔνθεο τιμῇ.»

This response contains a few curiosities for Homeric epic. For one, instead of valuing the past, it directly contests the past as matching up to the present. For another, it assumes audience knowledge of a multigenerational war tradition around the city of Thebes to make sense of this. As we talk about in our book, Homer’s Thebes, the sacks of Thebes and Troy are positioned as a cosmic pair in ending the race of Heroes. For the particular stance of the Iliad, however, it is important to raise up the heroes of its epic: Diomedes and Sthenelos were heroic enough to take care of Thebes when their fathers could not; and yet, despite that, Troy is so much of a bigger deal that Diomedes and Sthenelos are merely role players on a much larger team.

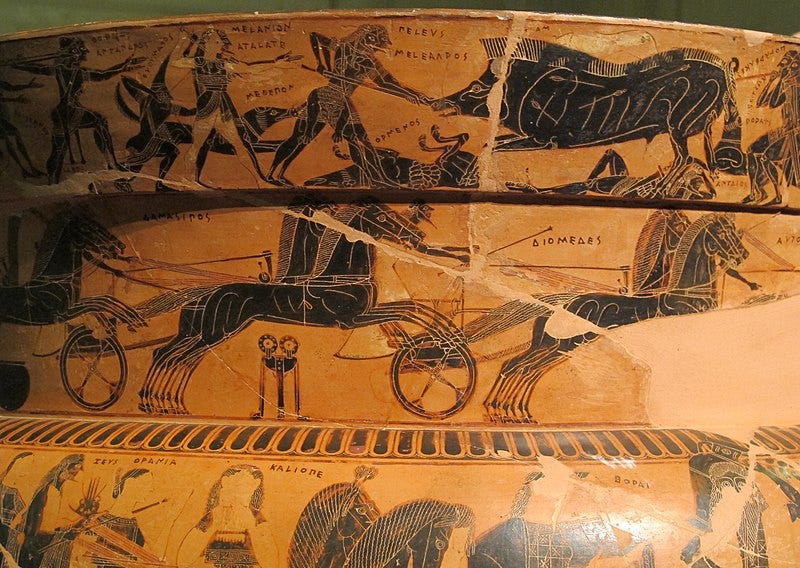

But what of the tradition they are referring to? We have broad and deep evidence for narratives around Thebes from early iconography (8th century BCE) through extant and fragmentary dramas on the Athenian stage. But there is also a tradition of epic poetry more-or-less contemporaneous with Homer and Hesiod. Pausanias, the later travel writer, even claims that the Thebais was best, after the Iliad and the Odyssey (see below). The primary texts that may be targets of Homeric play here, are the Thebais and the Epigonoi.

Take these fragments with healthy skepticism, however. It is likelier that Homeric poetry was competing with Theban narratives in general rather than particular poems. And, of course, we always run the risk of a scholarly circularity with these fragments as well: they have been largely preserved in scholarly traditions commenting on and explaining the canonized texts of Homer and the Greek Tragedians. In our work, Elton and I don’t believe that we can accurately reconstruct Theban narratives from extant Homeric poetry, since the Iliad and the Odyssey strive so far to establish themselves as authoritative narratives.

The remains of an ancient epic called the Thebais that was attributed to ‘Homer’ by multiple sources in antiquity (although most scholars today, following Aristotle, agree that ‘Homer’ = Iliad and Odyssey or something like that). This epic seems to have told the Theban tale from the cursing of Polyneices and Eteocles by Oedipus through the events of the Seven Against Thebes.

Pausanias, IX 9.5

“The epic called Thebais was composed about this war. Kallinos, when he comes to mention this epic, says that Homer composed it. Many authors of considerable repute have believed the same thing. And I like this poem especially, after the Iliad and Odyssey at least.”

ἐποιήθη δὲ ἐς τὸν πόλεμον τοῦτον καὶ ἔπη Θηβαΐς• τὰ δὲ ἔπη ταῦτα Καλλῖνος ἀφικόμενος αὐτῶν ἐς μνήμην ἔφησεν ῞Ομηρον τὸν ποιήσαντα εἶναι, Καλλίνῳ δὲ πολλοί τε καὶ ἄξιοι λόγου κατὰ ταὐτὰ ἔγνωσαν• ἐγὼ δὲ τὴν ποίησιν ταύτην μετά γε ᾿Ιλιάδα καὶ τὰ ἔπη τὰ ἐς ᾿Οδυσσέα ἐπαινῶ μάλιστα.

Fragments of the Thebais

Fr. 1 (found in The Contest of Homer and Hesiod)

“Goddess, sing of very-thirsty Argos, from where the Leaders [departed for Thebes]”

῎Αργος ἄειδε, θεά, πολυδίψιον, ἔνθεν ἄνακτες

Fr. 2 (Found in Athenaeus’ Deipnosophists)

“Then the god-bred hero, blond Polyneices,

First placed before Oedipus a fine silver platter,

A thing of god-minded Kadmos. And then

He filled a fine golden cup with sweet wine.

But when he noted that lying before him were the

Honored gifts of his own father, a great evil filled his heart.

Quickly he uttered grievous curses against both

Of his own sons—and he did not escape the dread Fury’s notice—

That they would not divide their inheritance in friendship

But that they would both have ceaseless war and battles.”αὐτὰρ ὁ διογενὴς ἥρως ξανθὸς Πολυνείκης

πρῶτα μὲν Οἰδιπόδηι καλὴν παρέθηκε τράπεζαν

ἀργυρέην Κάδμοιο θεόφρονος• αὐτὰρ ἔπειτα

χρύσεον ἔμπλησεν καλὸν δέπας ἡδέος οἴνου.

αὐτὰρ ὅ γ’ ὡς φράσθη παρακείμενα πατρὸς ἑοῖο

τιμήεντα γέρα, μέγα οἱ κακὸν ἔμπεσε θυμῶι,

αἶψα δὲ παισὶν ἑοῖσιν ἐπ’ ἀμφοτέροισιν ἐπαρὰς

ἀργαλέας ἠρᾶτο• θοὴν δ’ οὐ λάνθαν’ ᾿Ερινύν•

ὡς οὔ οἱ πατρώϊ’ ἐνηέι φιλότητι

δάσσαιντ’, ἀμφοτέροισι δ’ ἀεὶ πόλεμοί τε μάχαι τε

Fr.4 (Found in Scholion to Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus, 1375)

“When [Oedipus] noticed the cut of meat, he hurled it to the ground and spoke:

‘Alas, my children have sent this as a reproach to me…’

He prayed to King Zeus and the other gods

That they would go to Hades’ home at each other’s hands.ἰσχίον ὡς ἐνόησε, χαμαὶ βάλεν εἶπέ τε μῦθον•

‘ὤ μοι ἐγώ, παῖδες μέγ’ ὀνειδείοντες ἔπεμψαν …’

*

εὖκτο Διὶ βασιλῆϊ καὶ ἄλλοις ἀθανάτοισι

χερσὶν ὑπ’ ἀλλήλων καταβήμεναι ῎Αιδος εἴσω.

Fragments of the Epigonoi

As early as Herodotus (4.32) it was doubted that the epic that told the story of the sons of the Seven Against Thebes was by Homer. Instead, it was attributed later to a man named Antimachus from Teios. We have two lines most people agree on, and a handful of uncertain lines.

Fr. 1 (From the Contest of Homer and Hesiod)

“Now, Muses, let us sing in turn of the younger men”

Νῦν αὖθ’ ὁπλοτέρων ἀνδρῶν ἀρχώμεθα, Μοῦσαι

Fr. 4 (From Clement of Alexandria)

“Many evils come to men from gifts”

ἐκ γὰρ δώρων πολλὰ κάκ’ ἀνθρώποισι πέλονται.

Fr. 6 (Dub. from the Contest of Homer and Hesiod)

“So then they divided the meat of bulls and wiped clean

The sweat-covered necks of horses, since they had their fill of war.”ὣς οἱ μὲν δαίνυντο βοῶν κρέα, καὐχένας ἵππων

ἔκλυον ἱδρώοντας, ἐπεὶ πολέμοιο κορέσθην.

Fr. 7 (Dub. From Scholia to Aristophanes’ Peace)

“They girded themselves for war once they stopped….

And they poured out of the towers as an invincible cry arose.”θωρήσσοντ’ ἄρ’ ἔπειτα πεπαυμένοι

πύργων δ’ ἐξεχέοντο, βοὴ δ’ ἄσβεστος ὀρώρει.

Bibliography on rivalry and Thebes

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know. If there is anything you’d like to read that you don’t have free access to, let me know.

Barker, E.T.E. . 2009. Entering the Agon: Dissent and Authority in Homer, Historiography and Tragedy. Oxford.

Barker, E. T. E., and J. P. Christensen. 2006. “Flight Club: The New Archilochus Fragment and its Resonance with Homeric Epic.” Materiali e Discussioni per l’Analisi dei Testi Classici 57:19–43.

———. 2008. “Oedipus of Many Pains: Strategies of Contest in Homeric Poetry.” Leeds International Classical Studies 7.2. (http://www.leeds.ac.uk/classiscs/lics/)

———. 2011. “On Not Remembering Tydeus: Diomedes and the Contest for Thebes.” Materiali e discussioni per l’analisi dei testi classici 66:9–44.

———. 2014. “Even Herakles Had to Die: Epic Rivalry and the Poetics of the Past in Homer’s Iliad.” Trends in Classics: Homer and the Theban Tradition, ed. Christos Tsagalis, 249–277.

Christensen, Joel. 2018. “Eris and Epos: Composition, Competition and the ‘Domestication’ of Strife.” YAGE.

Cingano, E. 1992. “The Death of Oedipus in the Epic Tradition.” Phoenix 46:1–11.

———. 2000. “Tradizioni su Tebe nell’epica e nella lirica greca arcaica.” In La città di Argo: Mito, storia, tradizioni poetiche, ed. P. A. Bernardini, 59–68. Rome.

———. 2004. “The Sacrificial Cut and the Sense of Honour Wronged in Greek Epic Poetry: Thebais frgs. 2-3D.” In Food and Identity in the Ancient World, ed. C. Grotanelli and L. Milano, 269–279. Padova.

Collins, Derek. . 2004. Master of the Game: Competition and Performance in Greek Poetry. Hellenic Studies 7. Washington DC.

Davies, Malcolm. 2014. The Theban Epics. Hellenic Studies 69. Washington, DC.

Elmer, D. 2013. The Poetics of Consent: Collective Decision-Making and the Iliad. Baltimore.

Griffith, M. 1990. “Contest and Contradiction in Early Greek Poetry.” In Griffith and Mastronade 1990:185–207.

Irwin, Elizabeth. 2005. “Gods Among Men? The Social and Political Dynamics of the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women.” In Hunter 2005: 35–84.

Martin, Richard. 1989. The Language of Heroes: Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Ithaca.

Nagy, Gregory. 1979/1999. The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek poetry. Baltimore.

Pucci, Pietro. 1987. Odysseus Polutropos: Intertextual Readings in the Iliad and the Odyssey. Ithaca.

Scodel, Ruth. 2008. Epic Facework. Swansea.

Tsagalis, C. 2008. The Oral Palimpsest: Exploring Intertextuality in the Homeric Epics. Washington, DC.