This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations.

Book 11 of the Iliad is filled with action. But it begins with a sunrise. This particular dawn resets the action for the poem and is a good example of how much resonance with myth and other traditions the Homeric narrator can create with just a few words.

Iliad 11.1-14

Then Dawn rose from her bed alongside glorious Tithonos

In order to bring light to the immortal and mortals alike.

But Zeus sent Strife to the swift ships of the Achaeans,

Harsh strife, clutching an omen of war in its hands.

It stood on the dark sear-faring vessel of Odysseus,

And then bellowed in the middle in both directions.

First to the shelters of Ajax, the son of Telamon

And then to those of Achilles—they had pulled their ships up

At the farthest ends, because they trusted in their bravery and strength.

She stood there tall and shouted terribly, loudly,

And imbued the heart of each Achaean who hear her

With the great strength needs to fight and battle without end.

For them, war became sweeter than returning home

In their hollow ships to their dear fatherland.”᾿Ηὼς δ’ ἐκ λεχέων παρ’ ἀγαυοῦ Τιθωνοῖο

ὄρνυθ’, ἵν’ ἀθανάτοισι φόως φέροι ἠδὲ βροτοῖσι·

Ζεὺς δ’ ῎Εριδα προΐαλλε θοὰς ἐπὶ νῆας ᾿Αχαιῶν

ἀργαλέην, πολέμοιο τέρας μετὰ χερσὶν ἔχουσαν.

στῆ δ’ ἐπ’ ᾿Οδυσσῆος μεγακήτεϊ νηῒ μελαίνῃ,

ἥ ῥ’ ἐν μεσσάτῳ ἔσκε γεγωνέμεν ἀμφοτέρωσε,

ἠμὲν ἐπ’ Αἴαντος κλισίας Τελαμωνιάδαο

ἠδ’ ἐπ’ ᾿Αχιλλῆος, τοί ῥ’ ἔσχατα νῆας ἐΐσας

εἴρυσαν ἠνορέῃ πίσυνοι καὶ κάρτεϊ χειρῶν

ἔνθα στᾶσ’ ἤϋσε θεὰ μέγα τε δεινόν τε

ὄρθι’, ᾿Αχαιοῖσιν δὲ μέγα σθένος ἔμβαλ’ ἑκάστῳ

καρδίῃ ἄληκτον πολεμίζειν ἠδὲ μάχεσθαι.

τοῖσι δ’ ἄφαρ πόλεμος γλυκίων γένετ’ ἠὲ νέεσθαι

ἐν νηυσὶ γλαφυρῇσι φίλην ἐς πατρίδα γαῖαν.

When I returned to this passage, I was at first a bit perplexed by the beginning. It is not uncommon to reset the plot or mark changes in the action with daybreaks in Homer. Indeed, dawn often anticipates the beginning of an assembly (divine or mortal, cf. Iliad 8.1 “When yellow-robed Dawn stretched over the whole earth…” ᾿Ηὼς μὲν κροκόπεπλος ἐκίδνατο πᾶσαν ἐπ' αἶαν [cf. 19.1; 24.295]). There are some variations in the expressions, and the introductory dawn is much more regular in the Odyssey (see, e.g. ἦμος δ' ἠριγένεια φάνη ῥοδοδάκτυλος ᾿Ηώς, 4.306) But there’s really no parallel for what happens in this passage: the mention of Tithonos, followed by the immediate divine intervention described here.

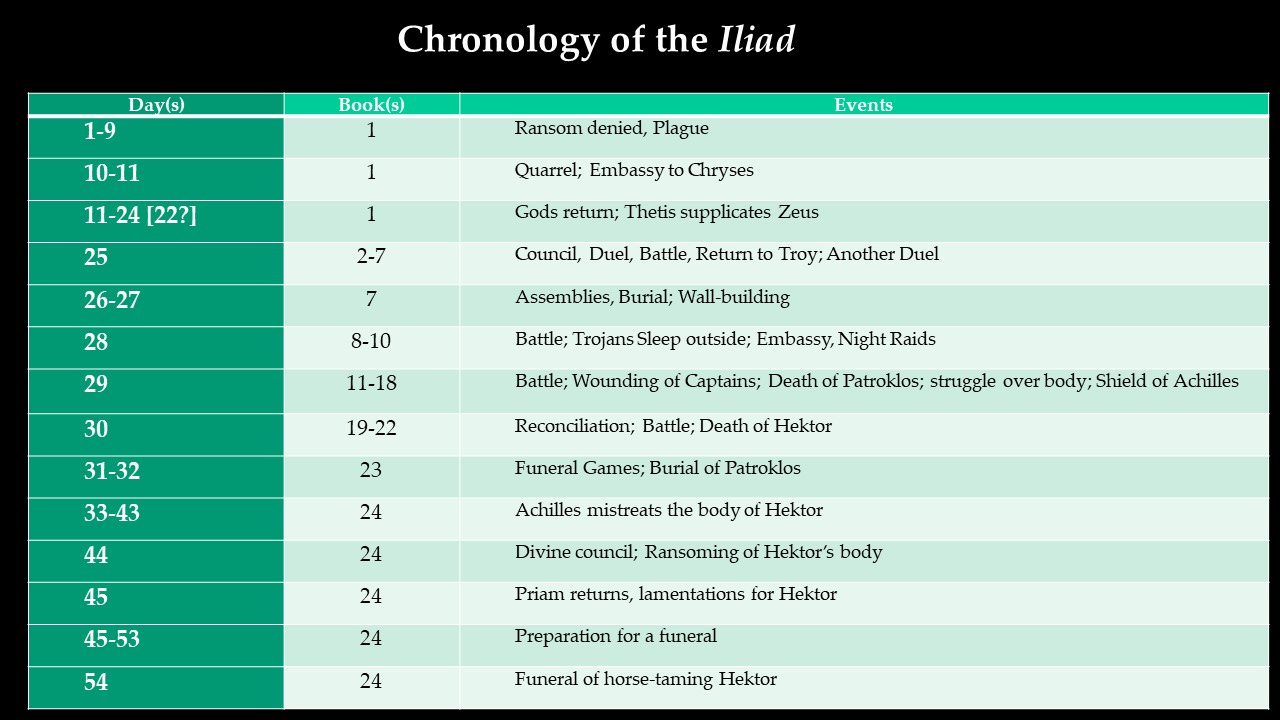

There are a few ways to understand what this passage is doing, I think. First, this exceptional re-beginning marks the epic’s longest day. As I discuss in a post on book 13, books 11-18 comprise a majority of the central action of the epic, but cover a single day in the action (day 29, depending on how you count). So, an exceptional introduction would be called for here. But I don’t think that covers it.

In addition to the length of the day, Zeus sending Eris may have thematic and generic implications as well. As I discuss in an article from YAGE, eris is both a thematic marker and a titling function in Greek epic. It is the kind of story that is typical of Homeric epic while also being characteristic of the cultural force that generated epic. Here, I think we can imagine the reinvocation of eris here as emphasizing the conflict about to come, but also as refocusing the cosmic nature of this poem.

The proem to the Iliad mentions eris twice: first, it asks the Muse to start the tale from a time when “those two men first fell out in strife” (ἐξ οὗ δὴ τὰ πρῶτα διαστήτην ἐρίσαντε, 1.6) and then “what god first set them to struggle in strife” (Τίς τάρ σφωε θεῶν ἔριδι ξυνέηκε μάχεσθαι; 1.8). The answer to the second question is disharmonious with what happens after book 1, when Zeus takes over the plot and causes the Greeks to lose in order to honor Achilles. This redeployment of a personified strife here, at the beginning of book 11, re-instantiates the conflict at Zeus’ behest and between the Greeks and Trojans, rather than between Agamemnon and Achilles. This reinitiates questions about the relationship between human agency and Zeus’ plan as well.

But wait, there’s more! Note as well the pains taken to describe Achilles’ and Ajax’s dwellings as on either end of the Greek fleet with Odysseus in the middle. As Jenny Strauss Clay shows in Homer’s Trojan Theater (2011), the battle books following Iliad 11 are consistent in the way they lay out the actions across the imagined geography of the poem. This opening resituates the audience in time and space before the most complex and prolonged violence of the poem.

And the last question, the one that got be started to begin with, is why is Tithonos invoked here and not elsewhere in the poem. The scholia to the Iliad are not incredibly helpful here, but they do bring up some salient points: first, Tithonos was a Trojan, and famously so. Second, he is known from the story told in the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite for being the unwitting victim of an apotheosis gone wrong. Dawn famously asked Zeus to make Tithonos immortal (that is, deathless) but not eternally young (or ageless). In the poetics of Greek myth, divine immortality is bipartite, requiring both deathlessness (a-thanatoi, immortals, literally means deathless ones) and agelessness (a-gerws). As a result, Tithonos grows older and older until he turns into (something like) a cicada and can only be heard.

It is hard to see at first glance how this can be appropriate for the beginning of book 11, but I suspect it works like this. Tithonos is a Trojan and he is in a place in medias res in relationship to his overall narrative, the story most people know. He is not a cicada yet, because he is still glorious and in bed with dawn. His appearance both invokes the closeness of the Trojans to the gods but also subtly implies that their story too is in the midst of its telling and everyone knows it is going to turn out badly.

(Some may suggest that this also recalls the child of Dawn and Tithonos, Memnon, who leads the fight for the Trojans after Hektor’s death. The Iliad and the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite both seem rather uninterested in Memnon’s very existence.)

If my interpretation is right, there may also be a connection to Zeus here: as an agent he is uniquely responsible for Trojan prominence (lover of Ganymede, judge who caused Apollo and Poseidon to build the Trojan walls) and as the chief god he is also uniquely responsible for the mixed promises and tricky plans that yield unexpected consequences. There’s a warning here, but also a metaphysical reinforcement. Like the old man who briefly lived alongside a goddess, the Trojan successes will be brief. The cicada’s song remains alongside Troy’s tragic fame, after the worse part of the stories have ended.

One might reasonably ask whether this is simply a reflection on the mortal condition.