This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 24. Here is a link to the overview of Iliad 23 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

How does one bring the Iliad to a close? How does one begin to write about this epic’s end? Do we start with the image of Priam kissing the hands of the man who killed his son? Do we try to make sense of the story Achilles tells of a Niobe who stopped to eat while she was weeping en route to her transformation to stone? Do we interweave all of the ends that are tied up alongside those left dangling in the completion of this overwhelming tapestry?

One of the finest scholarly responses is C.W. MacLeod’s commentary on the book. I tend to think that there is so much going on that a line by line response is the only way to make sense of what the book achieves: it addresses the major tensions lingering since book 1 without resolving them altogether by providing an understated coda to the political plot, offering transitional movement from the world of the living to the dead and back again, arranging for the themes of reciprocity and ransom to be revisited in the meeting of Priam and Achilles, providing an ambiguous yet moving testimony to Achilles’ change in character, and revisits the generative power of mourning with the women’s lament for Hektor and his funeral.

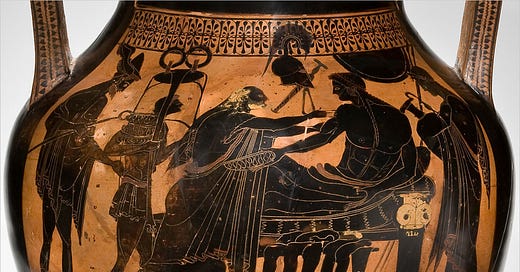

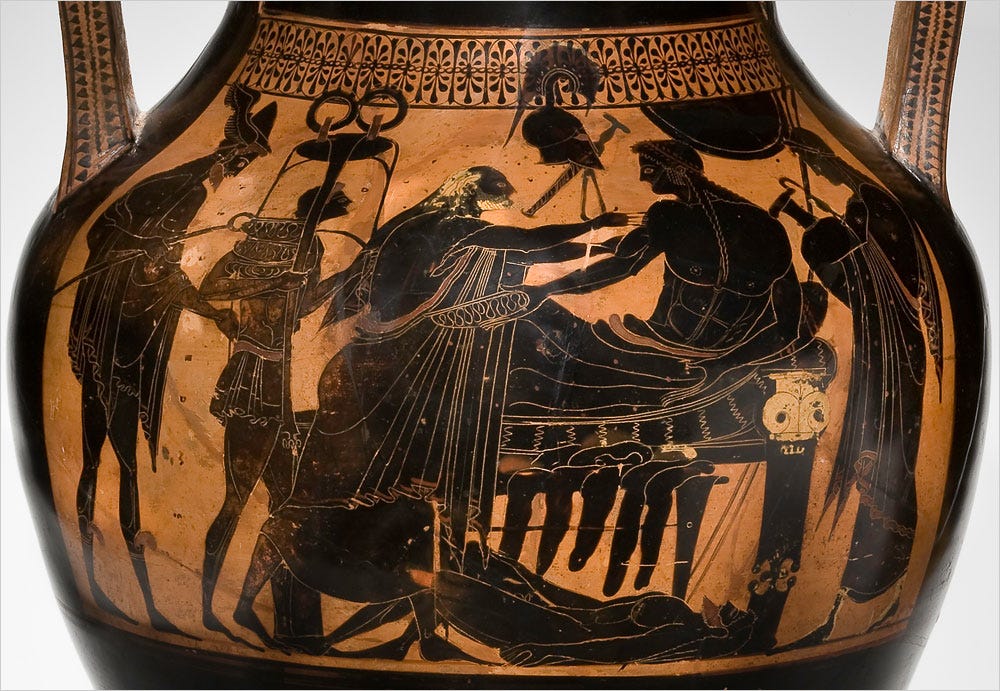

Of course, much of the action of the Iliad’s final book is forgotten because of the power of its most famous scene, the meeting of Achilles and Priam for the ransoming of Hektor’s body. The iconography of this scene is widespread enough in early Greece for me to believe that it was an episode independent of our Iliad—so how it is integrated into our particular epic is of great moment here. The book starts with Achilles’ unrelenting abuse of Hektor’s corpse, followed by a divine assembly to decide what to do over his behavior. Hera and Apollo argue against each other and Zeus intercedes on Hektor’s behalf. Hermes guides Priam at some length (and in secret) to Achilles’ dwelling where the famous meeting takes place. Priam returns with a guarantee for an armistice to arrange a funeral; Andromache, Hekuba, and Helen provide funerary laments for Hektor and the epic ends with his burial

Each the book adds something to the themes I have outlined in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions. Among these, however, I think for book 24 to do its job, it needs to resonate with all five of these themes. And, I think I will likely do more than three posts to bring this epic to a close.

The ‘Trial’ of Achilles

To start, let’s take a closer look at the opening deliberative scene in book 24. It addresses the relationship between Gods and Humans and also adjusts our expectations for heroic life (and death). [N.B. I have repurposed some unpublished material from my dissertation for what follows.] But most importantly, it signals a different approach to politics. As I have discussed before, the Iliad examines politics on three separate stages, one each for the Achaeans and Trojans, and the third is among the gods. Divine power operates differently because Zeus’ authority (allegedly) guarantees every god’s place in a fixed universe.

The message of the Iliad’s political interest is in part that human institutions cannot mirror divine ones because humans collectively change and individuals are subject to our torrent of self-interest and emotions. In addition to the thematic echoes/resonances, there are also some important structural returns. We find out at the beginning of Iliad 24 that there has been a nine-day neîkos among the gods, mirroring the nine-day plague at the beginning of the epic. And this creates something of an epic long chiastic [AB B’ A’] structure. Ransom [denied]: 9 days of divine wrath [culminating in Achilles’ rage] :: 9 days of divine strife : Ransom [accepted, final resolution of Achilles’ rage] (Whitman and Reinhardt are really good on these structural correspondences.)

The epic’s final book, however, has to answer general issues remaining with the gods, while also responding to the structure of the first: foremost, how their own self-interest has perpetuated violence in the form of the Trojan War and the Iliad itself and, second, whether Homer’s gods can hope to stand for justice the way the divinities of the external audiences are expected to in later years. These questions are addressed in part by the final divine assembly where they guarantee the right of burial to all mortals, regardless of their lineage.

The divine conflict over the corpse has been about just how transgressive Achilles’ behavior has been and whether or not the gods should intervene to preserve Hektor for burial. Since he died in book 22, Hektor’s body has been preserved by the gods, but the emotional impact of his mutilation has not been limited. The internal human audience does not know that Hektor’s flesh has been preserved. With the exception of Hera, Poseidon, and Athena, the gods long for Hermes to steal him away. Apollo stands to address them all (24.33-54):

‘Gods, you are cruel, baneful. Didn’t Hektor always

burn the thigh pieces of bulls and full-grown goats for you?

Now you do not dare to save him, even as a corpse,

for his wife and mother and child to see,

and his father Priam and the host, who soon would

cremate him in fire and offer him a burial.

But you gods decide to help ruinous Achilles,

who has neither fateful thoughts nor flexible intention

in his heart, but he’s like a wild lion

who, after he gives in to his great force and proud heart,

goes after the flocks of mortals to take his feast,

so Achilles obliterates pity and has no shame

that thing that does so much in helping men.

Someone else would lose one so dear, I suppose,

either a brother of the same womb or a son,

but surely, after mourning and crying, he sets this aside;

for the Moirai gave men an enduring heart.

But this man, at least, after he has tied his horses

to shining Hektor, whose dear heart he extinguished,

he drags him around the grave marker of his dear companion—

that surely will not be better or finer for him.

Let us not be chastised by him even though he his noble;

For, indeed, he disfigures the fallow earth in his rage.’

Apollo speaks to show both that there is a clear majority for rescuing Hektor and that the majority is right with a poetic tour de force. As Richardson (1993, 280) notes in his commentary on the Iliad, this version of Apollo differs from the vengeful god of plague we meet in book 1 and closer to the god of prophecy and law who is more prominent in later years. First, he assails all the gods and appropriates Zeus’ language from book 4 in asking, rhetorically, whether or not Hektor was pious in his sacrifices. The implication is that, if Hektor was pious when alive, then he deserves the rites of burial. Apollo poetically expands this statement as he enumerates each member of Hektor’s funeral party (wife, mother, son, father, people). Then, he insists that, instead of helping Hektor, the gods help Achilles, a destructive man whose thoughts are not fitting and whose inhuman behavior he evokes with a surprising simile. By comparing Achilles to a lion who knows “wild” things, Apollo points to the politically destabilizing force he has had on the Achaeans and the uncivilized manner in which he is behaving. Not only does Apollo appropriate a theme from Zeus’ speech in book 4 (cf. 4.7) but instead of naming just those who have helped the Achaeans, he implicates all of the gods and insults them by their connection with ruinous acts against fate. Apollo, in the application of poetic devices, the appropriation of motifs from Zeus, and the manipulation of verbal persons, exploits a performance context where his ‘success’ depends conceptually on a majority approval, but realistically only on persuading Zeus.

The scene appears to proceed in the fashion of litigation. This is Apollo Lykaios, Apollo the barrister-god who appears in Aeschylus’ Oresteia, arguing against the Furies. The sought-after compromise between this particular, younger god, and an older figure of the earth and the matriarchy, Hera, would offer obvious parallels to ancient audiences. In her rebuttal, Hera defends inaction and attempts to manipulate the same performance dynamics (24.56-63):

‘This would only be your word, silver-bow,

if, indeed, you would set the same timê for Achilles and Hektor.

Hektor is mortal and nursed from a mortal woman and breast;

but Achilles is the offspring of a goddess whom I myself

raised and reared and I gave her as a wife to a man,

Peleus, who is dear to the heart of immortals.

You all attended the wedding; and you feasted among them,

holding your lyre, companion of evils, always untrustworthy.’

Hera claims, in a strange conditional, that if Apollo’s word were accepted, Hektor and Achilles would garner the same timê. Hera changes addressees during the speech, but her alteration is sudden (during the conditional), which may heighten the angry (if not irrational) tone of her speech. Hera aims the political language of valuation at the sensitivities of her audience. She attempts to depict a settlement as ridiculous through antithesis: Hektor is a mortal and was nursed by one, Achilles is not the same. Then, she accuses all the gods of being disingenuous since they all attended the wedding of Achilles’ parents. In closing, she calls Apollo a liar and implies that he is a hypocrite, because he performed at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis. Hera’s argument is posterior-focused—it emphasizes the relationships of the past, of a world that mixed gods and men. Apollo’s is anterior—he looks to a world in which the gods can authorize and champion some very basic values for mortals.

In his summary judgment, Zeus succinctly offers a verdict on the contest before him and occupies a more distant position from his engagement earlier in the epic, as if he never responded to Achilles’ plea at all. He briefly reflects the threat of neîkos inherent to Hera’s speech and then sets things in order quickly. Hera has little to say because Apollo has already won over Zeus, as his response makes clear (24.65-71):

‘Hera, really, don’t be completely angry with the gods.

Their timê [honor], at least, will not be the same. But Hektor

is also dearest to the gods of the mortals who live in Troy,

so he is to me, since he never missed dear gifts.

For my altar never lacked a fine feast,

both smoke and libation; for that is the share we have obtained.

But, certainly, we will not allow you to steal bold Hektor away

from Achilles in secret, there is no way. For his mother

always watches over him night and day the same.

But let someone of the gods call Thetis near me,

so I may speak some wise word, that Achilles

will accept gifts from Priam and ransom Hektor.’

Zeus starts with a negative imperative ἀποσκύδμαινε, a hapax legomenon (a word that occurs only once), to characterize the anger of Hera’s speech. The verb resonates well with the themes of irrational anger and political strife. Lexically, it appears to be related to éris. After depicting Hera as a politically dangerous and irrational speaker by using this verb, Zeus quickly dismisses her complaint about Achilles and Hektor earning the same timê and confirms that Apollo delivered the suggestion closest to his own perspective (Hektor is due funeral rites) by repeating his words from book 4 (4.48-9 = 24.69-70). Zeus’ response, however, is not a complete valorization of Apollo’s speech. Instead of relenting and having Hektor’s body stolen away, Zeus offers something of a compromise. At the same time, he retains his control over the narrative, his support of a world in which human sacrifices are observed, and the place of the basic right to burial.

The opening scene of Iliad 24 further justifies the separation between mortals and gods while also carving out a different kind of role for Zeus outside of this particular narrative. The importance of this scene is easier to appreciate if we consider the unfolding of events in this particular epic where leaders have repeatedly failed to resolve conflict. This movement repositions the gods to serve as examples for human beings and centralizes Zeus as the deity of justice more familiar from the Zeus presides over this scene as the king from Hesiod’s Theogony and Greek tragedy.

Hesiod Theogony, 80-93:

[Kalliope] is the Muse who attends to kings and singers.

Whomever of the god-raised Kings the daughters of great Zeus

Honor and look upon when he is born,

On his tongue they pour sweet dew

And gentle words flow out of his mouth. Then the people

All look upon him as he judges the laws

With straight decisions. He speaks confidently

And quickly resolves a conflict with skill.

For this reason, kings are intelligent, so that they

May effect retributive actions in the assembly when men are harmed,

And with ease as they persuade everyone with gentle words.

When he walks into the contest ground people propitiate him

Like a god with gentle reverence, and he stands out among the assembled.

Such is the gift of the muses for men.ἡ γὰρ καὶ βασιλεῦσιν ἅμ’ αἰδοίοισιν ὀπηδεῖ.

ὅντινα τιμήσουσι Διὸς κοῦραι μεγάλοιο

γεινόμενόν τε ἴδωσι διοτρεφέων βασιλήων,

τῷ μὲν ἐπὶ γλώσσῃ γλυκερὴν χείουσιν ἐέρσην,

τοῦ δ’ ἔπε’ ἐκ στόματος ῥεῖ μείλιχα· οἱ δέ νυ λαοὶ

πάντες ἐς αὐτὸν ὁρῶσι διακρίνοντα θέμιστας

ἰθείῃσι δίκῃσιν· ὁ δ’ ἀσφαλέως ἀγορεύων

αἶψά τι καὶ μέγα νεῖκος ἐπισταμένως κατέπαυσε·

τούνεκα γὰρ βασιλῆες ἐχέφρονες, οὕνεκα λαοῖς

βλαπτομένοις ἀγορῆφι μετάτροπα ἔργα τελεῦσι

ῥηιδίως, μαλακοῖσι παραιφάμενοι ἐπέεσσιν·

ἐρχόμενον δ’ ἀν’ ἀγῶνα θεὸν ὣς ἱλάσκονται

αἰδοῖ μειλιχίῃ, μετὰ δὲ πρέπει ἀγρομένοισι.

τοίη Μουσάων ἱερὴ δόσις ἀνθρώποισιν.

In the public space, subordinates offer competing visions and engage in verbal strife as evinced by Hera’s insults. Zeus listens to their speeches and then offers his own; his language presents a solution previously unavailable to prevent actual strife from developing. These parallels, however, quickly begin to collapse—the exchange loses its luster when compared to earlier conflicts in the Iliad. First of all, since the dispute is over men, the course of divine conflict in the Iliad has already determined that the stakes of such a contest are diminished. Second, the conflict is not with Zeus, but between factions of gods who spar with one another and expect him to orchestrate a resolution. Finally, the decision itself is a simple one. Although Zeus’ speech amounts to something of a compromise, he explains that there is a co-dependence between honors from men and honoring men. The import of this scene is undermined and left under-determined. And this is because there is still more work to be done. It is one thing to know that Achilles will return Hektor’s body; it is another to see it happen.

Short bibliography on the Book 24

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Bowie, Angus. “Narrative and emotion in the « Iliad »: Andromache and Helen.” Emotions and narrative in ancient literature and beyond: studies in honour of Irene de Jong. Eds. De Bakker, Mathieu, Van den Berg, Baukje and Klooster, Jacqueline. Mnemosyne. Supplements; 451. Leiden ; Boston (Mass.): Brill, 2022. 48-61. Doi: 10.1163/9789004506053_004

Carvounis, Katerina. “Helen and Iliad 24. 763-764.” Hyperboreus, vol. 13, no. 1-2, 2007, pp. 5-10.

Currie, Bruno. “The « Iliad », the « Odyssey », and narratological intertextuality.” Symbolae Osloenses, vol. 93, 2019, pp. 157-188. Doi: 10.1080/00397679.2019.1648002

Burgess, Jonathan Seth. “Untrustworthy Apollo and the destiny of Achilles: Iliad 24.55-63.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. 102, 2004, pp. 21-40.

Danek, Georg. “Achilles hybristēs ? : tisis and nemesis in Iliad 24.” Έγκλημα και τιμωρία στην ομηρική και αρχαϊκή ποίηση : από τα πρακτικά του ΙΒ' διεθνούς συνεδρίου για την Οδύσσεια, Ιθάκη, 3-7 Σεπτεμβρίου 2013. Eds. Christopoulos, Menelaos and Païzi-Apostolopoulou, Machi. Ithaki: Kentro Odysseiakon Spoudon, 2014. 137-152.

Ebbott, Mary. “The wrath of Helen: self-blame and nemesis in the « Iliad ».” Plato's « Laws » and its historical significance: selected papers of the I International Congress on Ancient Thought, Salamanca, 1998. Ed. Lisi, Francisco Leonardo. Sankt Augustin: Academia, 2001. 3-20.

Felson, Nancy. “« Threptra » and invisible hands: the father-son relationship in Iliad 24.” Arethusa, vol. 35, no. 1, 2002, pp. 35-50.

Franko, George Fredric. “The Trojan horse at the close of the « Iliad ».” The Classical Journal, vol. 101, no. 2, 2005-2006, pp. 121-123.

Hammer, Dean C.. “The « Iliad » as ethical thinking: politics, pity, and the operation of esteem.” Arethusa, vol. 35, no. 2, 2002, pp. 203-235.

Heath, Malcolm. “Menecrates on the end of the Iliad.” Rheinisches Museum für Philologie, vol. 141, no. 2, 1998, pp. 204-206.

Herrero de Jáuregui, Miguel. “Priam's catabasis: traces of the epic journey to Hades in Iliad 24.” TAPA, vol. 141, no. 1, 2011, pp. 37-68. Doi: 10.1353/apa.2011.0005

Kiss, Dániel. “Iliad 22.60 and 24.487: Priam on the threshold of old age.” Rheinisches Museum für Philologie, vol. 153, no. 3-4, 2010, pp. 401-404.

Knox, Ronald A.. “Iliad 24. 547-549: blameless Achilles.” Rheinisches Museum für Philologie, vol. 141, no. 1, 1998, pp. 1-9.

Kyriakou, Poulheria. “Reciprocity and gifts in the encounters of Diomedes with Glaucus and Achilles with Priam in the « Iliad ».” Hermes, vol. 150, no. 2, 2022, pp. 131-149. Doi: 10.25162/hermes-2022-0009

Mackie, Chris J.. “Iliad 24 and the judgement of Paris.” Classical Quarterly, N. S., vol. 63, no. 1, 2013, pp. 1-16. Doi: 10.1017/S0009838812000754

MacLeod, C. W., editor. Iliad, Book XXIV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pr., 1982.

Most, Glenn W.. “Anger and pity in Homer's « Iliad ».” Yale Classical Studies, vol. 32, 2003, pp. 50-75[JC1] .

Murnaghan, Sheila. “Equal honor and future glory: the plan of Zeus in the « Iliad ».” Classical closure: reading the end in Greek and Latin literature. Eds. Roberts, Deborah H., Dunn, Francis M. and Fowler, Don P.. Princeton (N. J.): Princeton University Pr., 1997. 23-42.

Pantelia, Maria C.. “Helen and the last song for Hector.” TAPA, vol. 132, 2002, pp. 21-27.

Perkell, Christine G.. “Reading the laments of Iliad 24.” Lament: studies in the ancient Mediterranean and beyond. Ed. Suter, Ann. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Pr., 2008. 93-117.

Karl Reinhardt. Die Ilias und ihr Dichter. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1961.

Rabel, Robert J.. “Apollo as a model for Achilles in the Iliad.” American Journal of Philology, vol. CXI, 1990, pp. 429-440.

Race, William H.. “Achilles’ κῦδος in Iliad 24.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 67, no. 5, 2014, pp. 707-724. Doi: 10.1163/1568525X-12341406

Nicholas Richardson. The Iliad: A Commentary. Volume VI: Books 21-24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Strauss Clay, Jenny. “Iliad 24.649 and the semantics of κερτομέω.” Classical Quarterly, N. S., vol. 49, no. 2, 1999, pp. 618-621. Doi: 10.1093/cq/49.2.618

Taplin, Oliver. “A word of consolation in Iliad 24, 614.” Studi Italiani di Filologia Classica, 3a ser., vol. 20, no. 1-2, 2002, pp. 24-27.

Thalmann, William G.. “« Anger sweeter than dripping honey »: violence as a problem in the « Iliad ».” Ramus, vol. 44, no. 1-2, 2015, pp. 95-114. Doi: 10.1017/rmu.2015.5[JC2]

Cedric Hubbell Whitman. Homer and the Heroic Tradition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Xian, Ruobing. “The dramatization of emotions in Iliad 24.552-658.” Philologus, vol. 164, no. 2, 2020, pp. 181-196. Doi: 10.1515/phil-2020-0105[JC3]

Zanker, Graham. “Beyond reciprocity: the Akhilleus-Priam scene in Iliad 24.” Reciprocity in ancient Greece. Eds. Gill, Christopher, Postlethwaite, Norman and Seaford, Richard A. S.. Oxford: Clarendon Pr., 1998. 73-92.