This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 13. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

One of the things I emphasized in my first post about Iliad 13 is how it features what we might thing of as the second or third string of Homeric heroes, an Idomeneus and a Meriones who echo other heroic pairs like Achilles and Patroklos, Diomedes and Sthenelos, or Sarpedon and Glaukos. These pairs may echo narrative structures that harken back to Gilgamesh and Enkidu in the Gilgamesh poems and persist to characters like Nisus and Euryalus in Vergil’s Aeneid.

The thematic pairing seems important for these heroes to have the therapon, a ritual assistant who can also be seen as a sacrificial replacement. There’s certainly a hero and sidekick phenomenon going on that’s interesting, but there are interesting psychological possibilities as well. Lenny Muellner has argued, following others, that Achilles and Patroklkos are a mirrored pair, substitutes if not doubles for each other to the extent that the represent the same person.

In addition to the symbolic exploration of identity, these pairs also allow audiences the opportunity to see heroes in friendships. I often wonder if there is some kind of a commentary on figures who don’t have these relationships or for whom they are problematic. In this, I am thinking primarily of Hektor whose relationships with his brother Paris and his countryman Polydamas are fraught at best. Rather than seeing this as an indictment of Hektor, we may see his lack of a double as a feature of his social and political deprivation. Perhaps we are meant to see Hektor as someone who, despite family and city, is essentially alone.

So, part of what I think is happening again in book 13 is an emphasis on the greater possibilities of the Achaean polity: the Greeks can withstand the Trojan onslaught because they have multiple leaders who can stand up and fight when others fall. This contrast with the Trojans is pointed in book 13 where we see Idomeneus and Meriones rally the Greeks against Hektor until he listens to Polydamas’ advice.

But wait, there’s MORE.

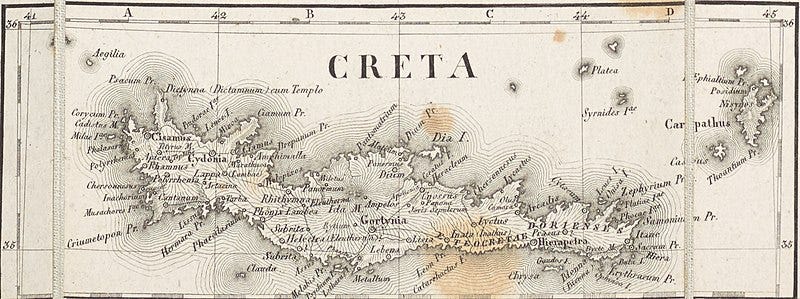

I suspect that the rise of Idomeneus in this passage is also about integrating Cretan mythic traditions into the Homeric narrative. Now, to explain this, a little foot work: As Elton Barker and I explore in Homer’s Thebes, the Homeric epics we possess demonstrate some kind of an appropriative relationship with other poetic traditions. Scholars are pretty sure that there were countless heroic traditions rolling around the Greek world prior to the classical age. Part of the success of the Iliad and the Odyssey is the integration of local traditions–also called epichoric–and other narrative patterns into their narratives. The Iliad does this most clearly in the Catalogue of Ships where i realizes a pretty nifty narrative trick: by creating a coalition narrative that brings heroes together from all over the world of Greek audiences to go against a common enemy in the east, the Iliad creates the perfect opportunity to bring those story traditions together and make them work for its narrative. In a slightly different way, the Odyssey does something similar in the stories Odysseus tells in the underworld in book 11: he subordinates other heroic traditions and genealogical traditions to his own story.

This is all part of the Homeric strategy to replace other traditions. As Christos Tsagalis writes in the Oral Palimpsest: “ ‘Homer’ then reflects the concerted effort to create a Pan-Hellenic canon of epic song. His unprecedented success is due…not to his making previous epichoric traditions vanish but to his erasing them from the surface of his narrative while ipso tempore employing them in the shaping of his epics” (2008, xiii). This process separates the local myths from their original context and transforms them into a different vehicle for Panhellenic identities. According to Gregory Nagy (1990:66) “myths that are epichoric…are still bound to the rituals of their native locales, whereas the myths of Panhellenic discourse, in the process of excluding local variations, can become divorced from ritual.”

Crete was an important place within the larger discourse: ancient myth positions Crete as a place of power, due to King Minos; and Greeks of later years had mostly lost the memory of the great Minoan cities on Crete, but not the shape of those memories. The Iliad and the Odyssey, however, seem to present Crete in somewhat different ways. Crete may have been a setting for different versions of the Odyssey.

There’s a minor debate about how many cities there were in Crete!

Schol. A. ad Il. 2.649

“Others have instead “those who occupy hundred-citied Crete” in response to those Separatists because they say that it is “hundred-citied Crete” here but “ninety-citied” in the Odyssey. Certainly we have “hundred-citied” instead of many cities, or he has a similar and close count now, but in the Odyssey lists it more precisely as is clear in Sophocles. Some claim that the Lakedaimonian founded ten cities.”

Ariston. ἄλλοι θ’ οἳ Κρήτην <ἑκατόμπολιν ἀμφενέμοντο>: πρὸς τοὺς Χωρίζοντας (fr. 2 K.), ὅτι νῦν μὲν ἑκατόμπολιν τὴν Κρήτην, ἐν ᾿Οδυσσείᾳ (cf. τ 174) δὲ ἐνενηκοντάπολιν. ἤτοι οὖν ἑκατόμπολιν ἀντὶ τοῦ πολύπολιν, ἢ ἐπὶ τὸν σύνεγγυς καὶ ἀπαρτίζοντα ἀριθμὸν κατενήνεκται νῦν, ἐν ᾿Οδυσσείᾳ δὲ τὸ ἀκριβὲς ἐξενήνοχεν, ὡς παρὰ Σοφοκλεῖ (fr. 813 N.2 = 899 P. = 899 R.). τινὲς δέ †φασι πυλαιμένη† τὸν Λακεδαιμόνιον δεκάπολιν κτίσαι.

Strabo, 10.15

“Because the poet sometimes calls Krete “hundred-citied” but at others, “ninety-cited”, Ephorus says that ten cities were founded after the battles at Troy by the Dorians who were following Althaimenes the Argive. But he also says that Odysseus names it “ninety-cities” This argument is persuasive. But others say that ten cities were destroyed by Idomeneus’ enemies. But the poet does not claim that Krete is “hundred-citied” during the Trojan War but in his time—for he speaks in his own language even if it is the speech of those who existed then, just as in the Odyssey when he calls Crete “ninety-citied”, it would be fine to understand it in this way. But if we were to accept that, the argument would not be saved. For it is not likely that the cities were destroyed by Idomeneus’ enemies when he was at war or came home from there, since the poet says that “Idomeneus led to Crete all his companions who survived the war and the sea killed none of them.

He would have mentioned that disaster. For Odysseus certainly would not have known of the destruction of the cities because he had not encountered any of the Greeks either during his wandering or after. And one who accompanied Idomeneus against Troy and returned with him would not have known what happened at home either during the expedition or the return from there. If Idomeneus was preserved with all his companions, he would have come back strong enough they his enemies were not going to be able to deprive him of ten cities. That’s my overview of the land of the Kretans.”

Most readers of early Greek poetry might remember that both Odysseus, in the Odyssey and Demeter, in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, use Cretan origins as ways to explain why they can speak Greek but are unknown to mainlanders. Crete is just Greek enough to be “Greek”, but foreign enough to mark a Cretan as ‘other’.

From the Suda

“To speak Cretan to Cretans: Since they liars and deceivers”

Κρητίζειν πρὸς Κρῆτας. ἐπειδὴ ψεῦσται καὶ ἀπατεῶνές εἰσι.

Zenobius, 4.62.10

“To be a Cretan: People use this phrase to mean lying and cheating. And they say it developed as a proverb from Idomeneus the Cretan. For, as the story goes, when there was a disagreement developed about the greater [share] among the Greeks at troy and everyone was eager to acquire the heaped up bronze for themselves, they made Idomeneus the judge. Once he took open pledges from them that they would adhere to the judgments he would make, he put himself in from of all the rest! For this reason, it is called Krêtening.”

Κρητίζειν: ἐπὶ τοῦ ψεύδεσθαι καὶ ἀπατᾶν ἔταττον τὴν λέξιν, καὶ φασὶν ἀπὸ τοῦ ᾿Ιδομενέως τοῦ Κρητὸς τὴν παροιμίαν διαδοθῆναι. Λέγεται γὰρ διαφορᾶς ποτὲγενομένης τοῖς ἐν Τροίᾳ ῞Ελλησιν περὶ τοῦ μείζονος, καὶ πάντων προθυμουμένων τὸν συναχθέντα χαλκὸν ἐκ τῶν λαφύρων πρὸς ἑαυτοὺς ἀποφέρεσθαι, γενόμενον κριτὴν τὸν ᾿Ιδομενέα, καὶ λαβόντα παρ’ αὐτῶν τὰς ἐνδεχομένας πίστεις ἐφ’ ᾧ κατακολουθῆσαι τοῖς κριθησομένοις, ἀντὶ πάντων τῶν ἀριστέων ἑαυτὸν προτάξαι. Διὸ λέγεσθαι τὸ Κρητίζειν.

There’s a fascinating myth that brings together these traditions of lying with Idomeneus and Achilles’ mother:

Medeia’s Beauty Contest: Fr. Gr. Hist (=Müller 4.10.1) Athenodorus of Eretria

“In the eighth book of his Notes, Athenodorus says that Thetis and Medeia competed over beauty in Thessaly and made Idomeneus the judge—he gave the victory to Thetis. Medeia, enraged, said that Kretans are always liars and she cursed him, that he would never speak the truth just as he had [failed to] in the judgment. And this is the reason that people say they believe that Kretans are liars. Athenodorus adds that Antiokhos records this in the second book of his Urban Legends.”

Ἀθηνόδωρος ἐν ὀγδόῳ Ὑπομνημάτων φησὶ Θέτιν καὶ Μήδειαν ἐρίσαι περὶ κάλλους ἐν Θεσσαλίᾳ, καὶ κριτὴν γενέσθαι Ἰδομενέα, καὶ προσνεῖμαι Θέτιδι τὴν νίκην. Μήδειαν δ ̓ ὀργισθεῖσαν εἰπεῖν· Κρῆτες ἀεὶ ψευσταὶ, καὶ ἐπαράσασθαι αὐτῷ, μηδέποτε ἀλήθειαν εἰπεῖν, ὥσπερ ἐπὶ τῆς κρίσεως ἐποίησε. Καὶ ἐκ τούτου φησὶ τοὺς Κρῆτας ψεύστας νομισθῆναι· παρατίθεται δὲ τοῦτο ἱστοροῦντα ὁ Ἀθηνόδωρος Ἀντίοχον ἐν δευτέρῳ τῶν Κατὰ πόλιν μυθικῶν.

Of course, in the Odyssey Idomeneus shows up in Odysseus’ lies

Od. 13.256-273

“I heard of Ithaca even in broad Krete

Far over the sea. And now I myself have come

With these possessions. I left as much still with my children

When I fled, because I killed the dear son of Idomeneus,

Swift-footed Orsilokhos who surpassed all the grain-fed men

In broad Krete with his swift feet

Because he wanted to deprive me of all the booty

From Troy, over which I had suffered much grief in my heart,

Testing myself against warlike men and the grievous waves.

All because I was not showing his father favor as an attendant

In the land of the Trojans, but I was leading different companions.

I struck him with a bronze-pointed spear as he returned

From the field, after I set an ambush near the road with a companion.

Dark night covered the sky and no human beings

Took note of us, I got away with depriving him of life.

But after I killed him with the sharp bronze,

I went to a ship of the haughty Phoenicians

And I begged them and gave them heart-melting payment.”“πυνθανόμην ᾿Ιθάκης γε καὶ ἐν Κρήτῃ εὐρείῃ,

τηλοῦ ὑπὲρ πόντου· νῦν δ’ εἰλήλουθα καὶ αὐτὸς

χρήμασι σὺν τοίσδεσσι· λιπὼν δ’ ἔτι παισὶ τοσαῦτα

φεύγω, ἐπεὶ φίλον υἷα κατέκτανον ᾿Ιδομενῆος,

᾿Ορσίλοχον πόδας ὠκύν, ὃς ἐν Κρήτῃ εὐρείῃ

ἀνέρας ἀλφηστὰς νίκα ταχέεσσι πόδεσσιν,

οὕνεκά με στερέσαι τῆς ληΐδος ἤθελε πάσης

Τρωϊάδος, τῆς εἵνεκ’ ἐγὼ πάθον ἄλγεα θυμῷ,

ἀνδρῶν τε πτολέμους ἀλεγεινά τε κύματα πείρων,

οὕνεκ’ ἄρ’ οὐχ ᾧ πατρὶ χαριζόμενος θεράπευον

δήμῳ ἔνι Τρώων, ἀλλ’ ἄλλων ἦρχον ἑταίρων.

τὸν μὲν ἐγὼ κατιόντα βάλον χαλκήρεϊ δουρὶ

ἀγρόθεν, ἐγγὺς ὁδοῖο λοχησάμενος σὺν ἑταίρῳ·

νὺξ δὲ μάλα δνοφερὴ κάτεχ’ οὐρανόν, οὐδέ τις ἥμεας

ἀνθρώπων ἐνόησε, λάθον δέ ἑ θυμὸν ἀπούρας.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ δὴ τόν γε κατέκτανον ὀξέϊ χαλκῷ,

αὐτίκ’ ἐγὼν ἐπὶ νῆα κιὼν Φοίνικας ἀγαυοὺς

ἐλλισάμην καί σφιν μενοεικέα ληΐδα δῶκα·

This is the first ‘lie’ Odysseus tells upon his arrival on Ithaca. He does not know that he is speaking to Athena and a scholiast explains his choices as if he were speaking to a suitor or one who would inform them.

Scholia V ad. Od. 13.267

“He explains that he killed Idomeneus’ son so that the suitors will accept him as an enemy of dear Odysseus. He says that he has sons in Crete because he will have someone who will avenge him. He says that the death of Orsilochus was for booty, because he is showing that he would not yield to this guy bloodlessly. He says that he trusted Phoenicians so that he may not do him wrong, once he has reckoned that they are the most greedy for profit and they spared him.”

τὸν μὲν ἐγὼ κατιόντα] σκήπτεται τὸν ᾿Ιδομενέως υἱὸν ἀνῃρηκέναι, ἵνα αὐτὸν πρόσωνται οἱ μνηστῆρες ὡς ἐχθρὸν τοῦ ᾿Οδυσσέως φίλου. ἑαυτῷ δὲ ἐν Κρήτῃ υἱούς φησιν εἶναι, ὅτι τοὺς τιμωρήσοντας ἕξει. καὶ τὸν ᾿Ορσιλόχου δὲ θάνατον λέγει διὰ τὴν λείαν, δεικνὺς ὅτι οὐδὲ ἐκείνῳ παραχωρήσει ἀναιμωτί. Φοίνιξι δὲ πιστεῦσαι λέγει, ἵνα μὴ ἀδικήσῃ, λογισάμενος ὅτι οἱ φιλοκερδέσταται αὐτοῦ ἐφείσαντο.

One of my favorite recent articles about book 13, by Grace Erny, looks closely at the role Idomeneus and Meriones play in this book. She argues that the depiction of the heroes in this book integrates “competing depictions of the Islands: one where Crete is well integrated into the Panhellenic world of the Achaeans and one where it stands out as a distinct region” (198). In doing so, I think the epic performs or even creates the Cretan dualism I mentioned above. Idomeneus and Meriones are just Greek enough to be part of the Achaean coalition but not so much as to escape the implication of difference and the echo of something perhaps more salacious.

Enry’s article lays out some of the material realities behind these traditions and also trace out the continuity of Crete’s depiction outside of the Iliad. In the latter part of the article, she looks at the relationship between the heroes and the ambiguity about their relative positions. Such ambiguity partners with their descriptions and actions to make it impossible to forget that they are Cretan, both advancing and confirming the Homeric strategy vis a vis Crete.

A starting bibliography on Book 13

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Cramer, David. “The wrath of Aeneas: Iliad 13.455-67 and 20.75-352.” Syllecta classica, vol. 11, 2000, pp. 16-33.

Erny, Grace. "Iliad 13, Homer’s Cretan Heroes, and “Cretan Exceptionalism”." Phoenix, vol. 74 no. 3, 2020, p. 197-219. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/phx.2020.0036.

Fenno, Jonathan Brian. “The wrath and vengeance of swift-footed Aeneas in Iliad 13.” Phoenix, vol. 62, no. 1-2, 2008, pp. 145-161.

Friedman, Rachel Debra. “Divine dissension and the narrative of the « Iliad ».” Helios, vol. 28, no. 2, 2001, pp. 99-118.

Kotsonas, Antonis. “Homer, the archaeology of Crete and the « Tomb of Meriones » at Knossos.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 138, 2018, pp. 1-35. Doi: 10.1017/S0075426918000010

McClellan, Andrew M.. “The death and mutilation of Imbrius in Iliad 13.” Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic, vol. 1, 2017, pp. 159-174. Doi: 10.1163/24688487-00101007

Nagy, G. 1990. Pindar’s Homer: the Lyric Possession of an Epic Past. Baltimore.

Panegyres, Konstantine. “Ὄρεϊ νιφόεντι ἐοικώς: Iliad 13.754-755 revisited.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 70, no. 3, 2017, pp. 477-487. Doi: 10.1163/1568525X-12342271

Saunders, Kenneth B.. “The wounds in Iliad 13-16.” Classical Quarterly, N. S., vol. 49, no. 2, 1999, pp. 345-363. Doi: 10.1093/cq/49.2.345

Tsagalis, Christos. 2008. The Oral Palimpsest: Exploring Intertextuality in the Homeric Epics. Hellenic Studies Series 29. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.