This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. This post is part of my plan to share new scholarship on Homer. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Every time the Olympics come around, I find myself talking about ancient Greek athletics, even though the topic is a bit far outside my expertise. As a Homerist, these contests stick out in my mind because they are (1) part of the apparatus of Panhellenic culture with Homer that emerges before the classical period; (2) like Homer, they reflect a growing fantasy of a heroic age that appealed to elite culture in the Classical period; and (3) their spirit of competition and glory resonates with the questions that are posed—if never answers—by the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Both epics have athletic contests as scenes where internal (and external) audiences are invited to consider heroic ‘worth’ based on participation in games. In Odyssey 8, the young Phaeacian princes invite Odysseus to show what kind of a man he is by engaging in after-dinner competition. (He eventually bests them with a discus, after criticizing them for putting too much emphasis on appearances.) That epic’s centering of cleverness and de-centering of the conventional heroic physique is tied to the identity of its hero and the skills he needs to return home (as I try to tease out a bit in an essay on disability studies in Homer).

For the Iliad, the funeral games of Patroklos occupy nearly an entire book. In writing my posts for each of the Iliad’s books, I think I gave short shrift to the funeral games. This is a little ironic, since the final chapter of my dissertation focused almost entirely on the games and the job talk I developed from it certainly helped me get my first academic position! The games are central to the epic’s plot in allowing it to return to the themes of the conflict in book 1. Oliver Taplin has argued that “one of the main poetic functions of the funeral games [is] to show Achilles soothing and resolving public strife, instead of provoking and furthering it” (1992, 253) and other authors who write on politics in Homer have seen these connections explicitly, including, but not limited to, Donna Wilson, Dean Hammer, Deborah Beck, Walter Donlan, David Elmer, Elton Barker, and more!

Games are never just about play and fun! They are opportunities for individuals to compete, but when communities are involved, they are also a form of deferred or transformed strife, nearly always loci of political posturing and the exploration of inter-social hierarchies. One just needs to check out ESPN’s Medal Tracker to note, even if superficially, that individual performance in the games is translated into some sign of collective worth or esteem. Further, we narrativize our own experiences and values through what happens on the screen: games are a place where we negotiate our differences and litigate what they mean. Consider recent controversies about gender, ongoing nationalistic feuds over clothing (though, mostly only what women are allowed to wear), and historical manipulation of the games.

The funeral games in Iliad 23 are an opportunity where Achilles experiments with new ideas about authority and the distribution of goods, resolving in part the conflict between him and Agamemnon lingering from book 1, but creating, I think a dissonance for external audiences about to what extent the solutions offered are available outside of epic.

I am not just reminded of the games because of the ongoing Olympics! In Charles Stocking’s Homer’s Iliad and the Problem of Force, which I have been reading and thinking about, the third chapter, “Force and Discourse in the Funeral Games of Patroclus”, presents an in depth reading of the games that adds to essential reading on the topic (work I have mentioned above, plus articles by Grethlein, Kelly and Kitchell cited below”.

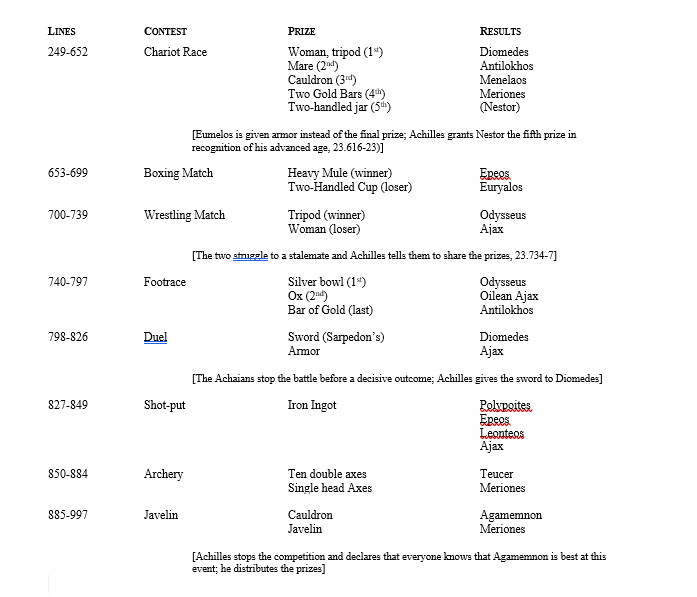

Stocking opens the chapter looking at the “problem of force” in the famous advice Nestor gives Antilochus before the chariot race. The race is the central part of the games and takes the longest amount of story time. It initiates a series of disputes and a pattern. The disputes are about the outcome of the contest where the presumed “best” competitors failed to meet expectations because of adverse luck (or questionable tactics). Achilles intervenes in several arguments and proposes solutions that provide new prizes from his personal store to restore/maintain the positions and honor of the competitors.

This would be the equivalent of an official from the IOC adding new medals to the competition. Imagine if the US Men’s basketball team loses a gold-medal game and a shocked world clamors for them to receive the top prize because everyone knows they have the best players! So, the IOC introduces a platinum medal for the team with the most talent and hype. This is a simplified form of what happens in book 23.

But there are many turns. Stocking’s full-chapter treatment is one of the most extensive and detailed analyses of the conflicts and prizes in the games that I know of. he goes through each of the major conflicts with a careful reading of the context and the language that makes it possible. He also introduces some alter work by Michel Foucault in which he discusses the games as a crucial point in “western” history’s exploration of “the will to truth”. Working with and through Foucault’s frameworks, Stocking provides a fine reading of Antilochus’ dispute with Menelaos as a complex negotiation of the fact that “the final distribution of prizes does not match up with the expectations outlined by the original sequence” (138).

During the chapter, Stocking focuses less on “force” directly than in the hierarchy of status implicit in the notion of who is best and the implications of the tension between assumed ability or excellence and outcomes due to accident or fate. In his words, the games become something of a “non-contest” because Achilles intervenes regularly abandoning “the logic of competition a a means for determining or representing social order” (166). Achilles, Stocking argues following others, replaces the contest by creating or recreating the order through his own “verbal performance”.

In this last detail, Stocking may miss an opportunity to set this Achilles as equivalent to the Odyssey’s Odysseus. Both heroes bend the perception of the cosmos for their audiences to their own liking, but both end up creating additional fantasies that may not have equivalents in the external worlds. Part of the disjuncture is the world of plenty heroes have to deal with: Achilles breaks with Agamemnon in book 1 over a slight to his honor when a distribution of goods is recalled in the king’s favor, yet repeatedly redistributes prizes in book 23, drawing from a store of goods that has no end. Odysseus comes home to punish the suitors for consuming his wealth, but there seems to be no end of meat and wine for feasting on Ithaka either. The worlds of Homer’s heroes approach no material limit.

The absence of this limit has a strange relationship with competition: for a feat to have value, it needs a context—we communicate ours by historicizing records of accomplishments and commemorating with symbolic prizes. In the Iliad’s games, the heroic world seems to always be spilling over its ends. As Edith Hall argues in her forthcoming Achilles in Green, the world of Homer’s heroes is extractive and consumptive to the extreme, perhaps anticipating our own modern fiction of endless expansion, profits without end. Without a limit or canon for the heroic games, they become performances of identities reified by Achilles’ addition of prizes whenever the expected worth doesn’t play out as it is expected.

The tension here—I suspect—is that the goal of epic itself is compromised. While Achilles' never clearly chooses kleos aphthiton in exchange for his war-shortened life, the Iliad leaves us to assume that he nevertheless receives it. But kleos without end is as problematic as human honors that do not change regardless of what actually happens in the games. As Glaukos says, the lives of men are like the leaves that grow and fall. They—and anything related to them—cannot truly be aphthiton, “unwithered, imperishable” because they are made of perishable stuff.

Perhaps the tension in the games relies in this: it is both about replaying the politics of book 1 and trying to approach the deep disappointment of being an example of human greatness, as yet subject to the failures of human life. Achilles’ management of the games is a navigation through personal as well as political value. It is a prelude to the contemplation of mortality in book 24, rather than an exultation in the variety and wonder of human achievement.

my old overview of the funeral games

Short Bibliography

n.b. this is not exhaustive. please let me know if there are other articles to include.

Deborah Beck. Homeric Conversation. Washington, D.C.: Center for Hellenic Studies, 2005.

Christensen, J. (2021). Beautiful Bodies, Beautiful Minds: Some Applications of Disability Studies to Homer. Classical World 114(4), 365-393. https://doi.org/10.1353/clw.2021.0020.

Dunkle, Roger. “Nestor, Odysseus, and the μῆτις-βίη antithesis. The funeral games, Iliad 23.” Classical World, vol. LXXXI, 1987, pp. 1-17.

Ellsworth, J. D.. “Ἀγων νεῶν. An unrecognized metaphor in the Iliad.” Classical Philology, vol. LXIX, 1974, pp. 258-264.

Elmer, D.F. (2013). The Poetics of Consent: Collective Decision Making and the Iliad. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press., https://doi.org/10.1353/book.21075.

Grethlein, Jonas. “Epic narrative and ritual: the case of the funeral games in Iliad 23.” Literatur und Religion: Wege zu einer mythisch-rituellen Poetik bei den Griechen. Eds. Bierl, Anton, Lämmle, Rebecca and Wesselmann, Katharina. MythosEikonPoiesis; 1.1-2. Berlin ; New York: De Gruyter, 2007. 151-177.

Kelly, Adrian. “Achilles in control ? : managing oneself and others in the Funeral Games.” Conflict and consensus in early Greek hexameter poetry. Eds. Bassino, Paola, Canevaro, Lilah Grace and Graziosi, Barbara. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pr., 2017. 87-108. Doi: 10.1017/9781316800034.005

Kenneth F. Kitchell. “‘But the mare I will not give up’: The Games in Iliad 23.” The Classical Bulletin 74 (1998) 159-71.

Mouratidis, Ioannis. “Anachronism in the Homeric games and sports.” Nikephoros, vol. III, 1990, pp. 11-22.

Mylonas, George E. “Homeric and Mycenaean Burial Customs.” American Journal of Archaeology 52, no. 1 (1948): 56–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/500553.

Rengakos, Antonios. “Aethiopis.” The Greek Epic Cycle and its ancient reception : a companion. Eds. Fantuzzi, Marco and Tsagalis, Christos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pr., 2015. 306-317.

Roller, Lynn E. “Funeral Games in Greek Art.” American Journal of Archaeology 85, no. 2 (1981): 107–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/505030.

Scott, William C.. “The etiquette of games in Iliad 23.” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, vol. 38, no. 3, 1997, pp. 213-227.

Stocking, Charles. Homer’s Iliad and the Problem of Force, Oxford, 2024.

Oliver Taplin. Homeric Soundings: The Shape of the Iliad. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Christoph Ulf. “Iliad 23: die Bestattung des Patroklos und das Sportfest der “Patroklos-Spiele”: zwei Teile einer mirror-story.” in Herbert Heftner and Hurt Tomaschitz (eds.). Ad Fontes! Festschrift für Gerhard Dobesch zum 65 Geburtstag am 15. September 2004. Wien: Phoibos, 2004, 73-86.

Malcolm M. Willcock, ‘The funeral games of Patroclus’, Proceedings of the Classical Association, LXX. (1973) 36.

Donna F. Wilson. Ransom, Revenge, and Heroic Identity in the Iliad. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.