This is a post expanding on the introduction to Iliad 7. Reminder: all proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

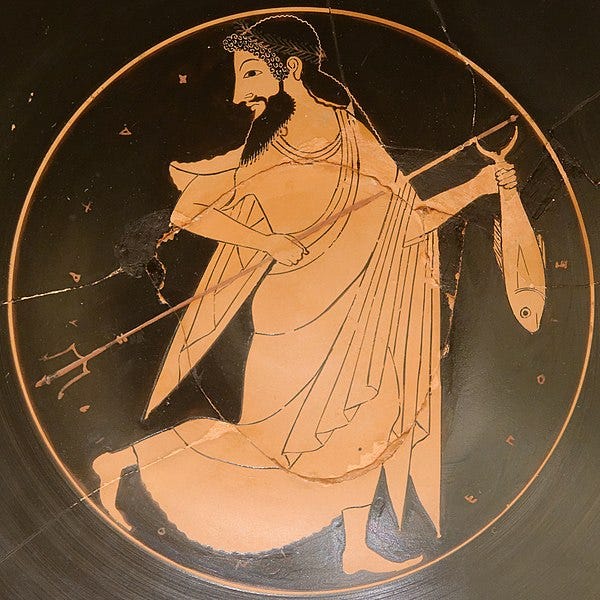

At the end of book 7, Poseidon complains to Zeus about the building of the Achaean Wall. In the broader mythical tradition, the walls of Troy were build by Apollo and Poseidon, who were forced to work for pay for Laomedon as punishment for rebellion against Zeus. Laomedon reneged on their pay and that led to a sea monster attacking the city and eventually Herakles’ attack. At this moment in the epic, however, Poseidon’s primary concern seems to be his own fame:

Iliad 6. 442-463

“So the long-haired Achaeans were toiling,

But the gods were seated next to Zeus the lighting-lord

Watching the great effort of the bronze-girded Achaeans.

Poseidon the earth-shaker began the speeches among them.

“Father Zeus, is there really any mortal on the boundless earth

Who would still tell his idea or plans to the immortals?

Don’t you see that the long-haired Achaeans now

Have built a wall around their ships and have hollowed

Out a trench around it but they did not make sacrifices to the gods?

The fame of this wall will reach as far as the dawn’s rise

And they will forget the wall that Phoebos Apollo and I built

Wearing ourselves out in toil for the hero Laomedon.”῝Ως οἳ μὲν πονέοντο κάρη κομόωντες ᾿Αχαιοί·

οἳ δὲ θεοὶ πὰρ Ζηνὶ καθήμενοι ἀστεροπητῇ

θηεῦντο μέγα ἔργον ᾿Αχαιῶν χαλκοχιτώνων.

τοῖσι δὲ μύθων ἦρχε Ποσειδάων ἐνοσίχθων·

Ζεῦ πάτερ, ἦ ῥά τίς ἐστι βροτῶν ἐπ’ ἀπείρονα γαῖαν

ὅς τις ἔτ’ ἀθανάτοισι νόον καὶ μῆτιν ἐνίψει;

οὐχ ὁράᾳς ὅτι δ’ αὖτε κάρη κομόωντες ᾿Αχαιοὶ

τεῖχος ἐτειχίσσαντο νεῶν ὕπερ, ἀμφὶ δὲ τάφρον

ἤλασαν, οὐδὲ θεοῖσι δόσαν κλειτὰς ἑκατόμβας;

τοῦ δ’ ἤτοι κλέος ἔσται ὅσον τ’ ἐπικίδναται ἠώς·

τοῦ δ’ ἐπιλήσονται τὸ ἐγὼ καὶ Φοῖβος ᾿Απόλλων

ἥρῳ Λαομέδοντι πολίσσαμεν ἀθλήσαντε.

Poseidon makes something of a procedural objection: The Greeks did not sacrifice before building the wall. Such neglect undermines the basic assumption of the Iliad, that sacrifices to the gods observe and in a way instantiate their honors and divine position. At some level, Poseidon’s concern is about the stability of honors drawn up in Hesiod’s Theogony> But he is also concerned about his own personal fame: he seems to articulate a zero-sum game of kleos, the fame of this wall will spread across the world and the wall he built will be forgotten. A scholiast makes a metapoetic inference here;

Schol. bT ad Hom. Il. 7.7.451

“perhaps this is because of the poetry. For the wall is a subject of song thanks to it, not because it was built by the Greeks, but because it appears in Homer because of the battle around it.”ex. τοῦ δ’ ἤτοι κλέος ἔσται, <ὅσην τ’ ἐπικίδναται ἠώς>: ἴσως διὰ τὴν ποίησιν αὐτοῦ· διὰ γὰρ ταύτην τὸ τεῖχος ἀοίδιμόν ἐστιν, οὐ δομηθὲν τοῖς ῞Ελλησιν, ἀλλ’ ῾Ομήρῳ γενόμενον ἕνεκεν τῆς ἐπ’ αὐτῷ μάχης.

Zeus responds to this complaint somewhat dismissively, but with a prediction for the future

Then cloud gathering Zeus addressed him,

“Come on, broad-strength, earthshaker what a thing to say!

Any other one of the gods would fear this thought,

One whose hands and drive are much weaker than yours.

Your fame will certainly reach as far as dawn’s rise.

Go when the long-haired Achaeans turn back

To go home to their dear land with their ships

And break the walls, pouring it all into the sea

And covering the broad beach with sand once again

So then you will erase the great wall of the Achaeans.”Τὸν δὲ μέγ’ ὀχθήσας προσέφη νεφεληγερέτα Ζεύς·

ὢ πόποι ἐννοσίγαι’ εὐρυσθενές, οἷον ἔειπες.

ἄλλός κέν τις τοῦτο θεῶν δείσειε νόημα,

ὃς σέο πολλὸν ἀφαυρότερος χεῖράς τε μένος τε·

σὸν δ’ ἤτοι κλέος ἔσται ὅσον τ’ ἐπικίδναται ἠώς.

ἄγρει μὰν ὅτ’ ἂν αὖτε κάρη κομόωντες ᾿Αχαιοὶ

οἴχωνται σὺν νηυσὶ φίλην ἐς πατρίδα γαῖαν

τεῖχος ἀναρρήξας τὸ μὲν εἰς ἅλα πᾶν καταχεῦαι,

αὖτις δ’ ἠϊόνα μεγάλην ψαμάθοισι καλύψαι,

ὥς κέν τοι μέγα τεῖχος ἀμαλδύνηται ᾿Αχαιῶν.

Notice how Zeus repeats Poseidon’s chief concern about his fame spreading as far as the dawn spreads (σὸν δ’ ἤτοι κλέος ἔσται ὅσον τ’ ἐπικίδναται ἠώς) and authorizes him to destroy the Achaean wall once the war is over. He confirms, in a way, Poseidon’s concerns about the zero-sum game of the walls, but does not really reflect on that metapoetic potential of the destruction of the walls to create a memory that exceeds that of the objects themselves. In a book like Iliad 7, where Hektor has made so much of the potential of a tomb on the Hellespont to ensure the kleos of himself and the man he kills, Poseidon’s promise to obliterate the structures on the shore threatens to undermine such faith in the physical monument in preference, perhaps, to the story being told.

This passage has some interesting political implications: in a way, Poseidon’s concern about the loss of his fame is not dissimilar to Achilles’ or Agamemnon’s worry about their loss of gerai and timai (prizes and honor), but there are also some metaphysical turns too: the gods evince a lack of knowledge about the future and a deep concern for human recognition.

But for Homeric scholars, one of the most troubling aspects of this passage is that some of it comes up again. According to the scholia, editors at the time of Zenodotus and Aristophanes of Byzantium, as well as Aristarchus, Athetized this entire section “about the destruction of the wall [because the poet] talks about it during the battle around the walls (12.3-35)” (ὅτι περὶ τῆς ἀναιρέσεως τοῦ τείχους λέγει πρὸ τῆς τειχομαχίας, Schol A. ad Hom. Il. 7.443). The ancient scholar Porphyry adds that it seems somewhat improper that heroes would build this wall and in addition illogical that it would take the gods nine days to erase what the Greeks built in a single day (Homeric Questions ad Il. 12)

Thucydides even gets in on this game when he says that the Achaeans constructed fortifications at the beginning of the war (1.9-11, leading some scholars like D. L. Page to surmise that Thucydides’ Iliad did not have an Achaean wall built in book 7). Such differences in detail have led some to see interpolation in book 7 or evidence for multiple authorship. I think that’s mostly nonsense and that there are good structural reasons for the repetition and the difference.

The description that comes in book 12 is much more elaborate:

Iliad 12.1-33

“So, while the valiant son of Menoitios was tending

To wounded Eurupulos in the tents, the Argives and Trojans

Were fighting in clusters. The ditch and the broad wall beyond

Were not going to hold, the defense they built for the ships

And the trench they made around it. They did not sacrifice to the gods

So that it would safeguard the fast ships and the piled up spoils

Held within it. It was built without the gods’ assent,

And so it would not remain steadfast for too much.

As long as Hektor was alive and Achilles was raging,

And as long as the city of lord Priam remained unsacked,

That’s how long the great wall of the Achaeans would be steadfast.But once however so many of the Trojans who were the best died

Along with many of the Argives who killed them, and the rest left,

And Priam’s city was sacked in the tenth year,

And the Argives went back to their dear homeland in their ships,

That’s when Poseidon and Apollo were planning

To erase the wall by turning the force of rivers against it.

All the number of the rivers that flow from the Idaian mountains to the sea,

Rhêsos, and Heptaporos, and Karêsos, and Rhodios,

And the Grênikos, and Aisêpos, and divine Skamandros

Along with Simoeis, where many ox-hide shields and helmets

Fell in the dust along with the race of demigod men.

Phoibos Apollo turned all of their mouths together

And sent them flowing against the wall for nine days.

And Zeus sent rain constantly, to send the walls faster to the sea.

The earthshaker himself took his trident in his hands

And led them, and he sent all the pieces of wood and stone

Out into the waves, those works the Achaeans toiled to make

And he smoothed out the bright-flowing Hellespont,

And covered the broad beach again with sands,

Erasing the wall, and then he turned the rivers back again,

He sent their beautiful flowing water back to where it was before.”῝Ως ὃ μὲν ἐν κλισίῃσι Μενοιτίου ἄλκιμος υἱὸς

ἰᾶτ’ Εὐρύπυλον βεβλημένον· οἳ δὲ μάχοντο

᾿Αργεῖοι καὶ Τρῶες ὁμιλαδόν· οὐδ’ ἄρ’ ἔμελλε

τάφρος ἔτι σχήσειν Δαναῶν καὶ τεῖχος ὕπερθεν

εὐρύ, τὸ ποιήσαντο νεῶν ὕπερ, ἀμφὶ δὲ τάφρον

ἤλασαν· οὐδὲ θεοῖσι δόσαν κλειτὰς ἑκατόμβας·

ὄφρά σφιν νῆάς τε θοὰς καὶ ληΐδα πολλὴν

ἐντὸς ἔχον ῥύοιτο· θεῶν δ’ ἀέκητι τέτυκτο

ἀθανάτων· τὸ καὶ οὔ τι πολὺν χρόνον ἔμπεδον ἦεν.

ὄφρα μὲν ῞Εκτωρ ζωὸς ἔην καὶ μήνι’ ᾿Αχιλλεὺς

καὶ Πριάμοιο ἄνακτος ἀπόρθητος πόλις ἔπλεν,

τόφρα δὲ καὶ μέγα τεῖχος ᾿Αχαιῶν ἔμπεδον ἦεν.αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ κατὰ μὲν Τρώων θάνον ὅσσοι ἄριστοι,

πολλοὶ δ’ ᾿Αργείων οἳ μὲν δάμεν, οἳ δὲ λίποντο,

πέρθετο δὲ Πριάμοιο πόλις δεκάτῳ ἐνιαυτῷ,

᾿Αργεῖοι δ’ ἐν νηυσὶ φίλην ἐς πατρίδ’ ἔβησαν,

δὴ τότε μητιόωντο Ποσειδάων καὶ ᾿Απόλλων

τεῖχος ἀμαλδῦναι ποταμῶν μένος εἰσαγαγόντες.

ὅσσοι ἀπ’ ᾿Ιδαίων ὀρέων ἅλα δὲ προρέουσι,

῾Ρῆσός θ’ ῾Επτάπορός τε Κάρησός τε ῾Ροδίος τε

Γρήνικός τε καὶ Αἴσηπος δῖός τε Σκάμανδρος

καὶ Σιμόεις, ὅθι πολλὰ βοάγρια καὶ τρυφάλειαι

κάππεσον ἐν κονίῃσι καὶ ἡμιθέων γένος ἀνδρῶν·

τῶν πάντων ὁμόσε στόματ’ ἔτραπε Φοῖβος ᾿Απόλλων,

ἐννῆμαρ δ’ ἐς τεῖχος ἵει ῥόον· ὗε δ’ ἄρα Ζεὺς

συνεχές, ὄφρά κε θᾶσσον ἁλίπλοα τείχεα θείη.

αὐτὸς δ’ ἐννοσίγαιος ἔχων χείρεσσι τρίαιναν

ἡγεῖτ’, ἐκ δ’ ἄρα πάντα θεμείλια κύμασι πέμπε

φιτρῶν καὶ λάων, τὰ θέσαν μογέοντες ᾿Αχαιοί,

λεῖα δ’ ἐποίησεν παρ’ ἀγάρροον ᾿Ελλήσποντον,

αὖτις δ’ ἠϊόνα μεγάλην ψαμάθοισι κάλυψε

τεῖχος ἀμαλδύνας· ποταμοὺς δ’ ἔτρεψε νέεσθαι

κὰρ ῥόον, ᾗ περ πρόσθεν ἵεν καλλίρροον ὕδωρ.

I don’t think that the ancient editors had much reason to athetize the passage from book 7. The two passages do very different things and where they fall in the epic matters. The first comes during a place in the plot where it makes sense for the wall to be built and Poseidon complains appropriately. The themes emphasized in the first section echo Hektor’s emphasis on kleos in book 5 and help to situate the Achaean Wall generally in time.

The wall’s second showing takes us into the future, just as the epic battle is about to increase in intensity and confusion. There no mention of kleos in the proleptic destruction of the wall. But there are several markers of the passage of time: the wall is related to the action of the story being told (it will last as long as Hektor lives and Achilles rages), it is situated within the Trojan War tradition (it will last through the sack of Troy), and it is marked as part of the destruction of the race of heroes, placing it in a cosmic outlook.

Lorenzo Garcia notes that the wall is in a way a metonym: “The wall—itself a stand-in for Achilles, as I argued above—here functions as an image of the tradition itself and its view of its own temporal durability” (2013, 191). Then he draws on Ruth Scodel’s work (1982) to note that this narrative necessarily positions the wall and the actions around it in a larger cosmic framework:

“ Scodel notes the general character of these narratives as marking a greater separation between gods and men; the former race of demigods (ἡμιθέων γένος ἀνδρῶν, XII 23) [20] is wiped out in a massive destructive event that brings the entire age to a decisive end. [21] What I wish to emphasize is the implication that in Iliad XII the Achaean wall is linked not merely with the figure of Achilles, for whom it functions as substitute, but with the entire heroic age which is to come to an end.”

I would like to add to this that the position of this temporal reminder at the middle of the epic, in the very book in which the wall is breached, is of structural significance. If we follow models of performance that split the Iliad into three movements, then the first mention of the Achaean walls’ destruction comes during a different performance. The secondary mention, then, is both a reminder and an expansion. It emphasizes different themes (extinction, destruction, erasure) in contrast to the former. And, in line with Homeric composition in general, it amplifies the discussion, taking the audience outside of the timeline of the Iliad temporarily before plunging us back into the chaos of war.

One final note on these passages: the balance of memory and forgetting, so clearly set out by Poseidon, appears to be tilted by divine agency. The verb that repeatedly marks Poseidon’s actions towards the Greek walls, amalduno, appears only in these particular passages in Homer. A scholion glosses it as coming from plunging into the sea (<ἀμαλδῦναι:> καθ’ ἅλμης δῦναι), perhaps responding both to Poseidon’s activity as a sea god and the cultural fear of the oblivion that comes from a death by shipwreck. Another place where this verb shows up in early Greek poetry is Bacchylides (14.1-6)

“Having good luck from god

Is the best thing for mortals.

But heavy-suffering accident

Can wipe out a good person

Even as it can raise a bad person on high

If it straightens them out.”Εὖ μὲν εἱμάρθαι παρὰ δαίμ[ονος ἀν]θρώ-

ποις ἄριστον·

[σ]υμφορὰ δ’ ἐσθλόν <τ’> ἀμαλδύ-

[νει β]αρύτλ[α]τος μολοῦσα

[καὶ τ]ὸν κακ[ὸν] ὑψιφανῆ

τεύ[χει κ]ατορθωθεῖσα·…

Here, instead of Poseidon or some other god, the force that “obliterates” is chance. Yet, this force seems to be one that implies layers of judgment, perhaps allowing for the fact that what survives for memory isn’t always the worthiest, just the luckiest. In this way, we can read Poseidon’s destruction of the Achaean walls as an act that attempts to erase one thing in favor of another, leaving open the possibility that narrative can outlast the erasure even as memory is no guarantee of virtue.

A Short bibliography on the Achaean Wall

Garcia, Lorenzo F., Jr. 2013. Homeric Durability: Telling Time in the Iliad. Hellenic Studies Series 58. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Heiden, B. (1996). The three movements of the iliad. Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 37(1), 5-22. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/three-movements-iliad/docview/229178418/se-2

Maitland, Judith. “Poseidon, Walls, and Narrative Complexity in the Homeric Iliad.” The Classical Quarterly 49, no. 1 (1999): 1–13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/639485.

PORTER, JAMES I. “Making and Unmaking: The Achaean Wall and the Limits of Fictionality in Homeric Criticism.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 141, no. 1 (2011): 1–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41289734.\

Purves, Alex. 2006a. “Falling into Time in Homer’s Iliad.” Classical Antiquity 25:179–209.

Scodel, Ruth. “The Achaean Wall and the Myth of Destruction.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 86 (1982): 33–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/311182.

H. W. Singor. “The Achaean Wall and the Seven Gates of Thebes.” Hermes 120, no. 4 (1992): 401–11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4476919.

Tsagarakis, Odysseus. “The Achaean Wall and the Homeric Question.” Hermes 97, no. 2 (1969): 129–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4475580.

West, M. L. “The Achaean Wall.” The Classical Review 19, no. 3 (1969): 255–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/707716.