This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 16. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

One of the most memorable scenes in the Iliad is when Zeus cries tears of blood once he accepts that his son Sarpedon is going to die. Sarpedon’s death is not necessarily crucial to the plot: Hektor could very easily kill Patroklos and thus redirect Achilles’ rage without Sarpedon’s presence at all. But this scene retains important thematic connections to the epic’s concern for heroism, human mortality, and widening the space between the worlds of gods and human beings.

Readers have identified internal and external tensions to this scene. Internally, Zeus predicted just in the last book that Sarpedon would die. Externally, there are scholarly traditions that see different kinds of inconsistency. One scholion suggests that “the poet” includes this passage to raise the profile of Sarpedon’s death (Schol. bT ad Il. 16.431-461) while another reports that Zenodotus questioned the entire conversation of Zeus and Hera (Schol. A) because it isn’t clear where or how this conversation is happening. A close reading of the scene can help us see its connections to larger epic and cosmic themes.

Iliad 16.431-438

“As the son of crooked-minded Kronos was watching them, he felt pity

And he addressed Hera, his sister and wife:

“Shit. Look, it is fate for the man most dear to me, Sarpedon,

To be overcome by Patroklos, son of Menoitios.

My hearts is split in two as I rush through my thoughts:

Either I will snatch him up still alive from the lamentable battle

And set him down in the rich deme of Lykia,

Or I will overcome him already at the hands of Patroklos.”

Note the movement from the statement of fate that seems impersonal (in Greek, μοῖρ' ὑπὸ Πατρόκλοιο Μενοιτιάδαο δαμῆναι) to the active statement I will with the somewhat interesting use of a temporal adverb pointing to now with a future verb (ἦ ἤδη ὑπὸ χερσὶ Μενοιτιάδαο δαμάσσω). Zeus expresses the very confusing overlap between his submission to fate and his status as an agency of it.

But any sensed contradiction here is understandable if we look at the metaphysical world the Iliad constructs itself: as Zeus says to Thetis in book 1, once he consents to a proposition, once he ‘nods’ to it, it moves from the unreal to a future fact. Part of Zeus’ power resides in the belief that his word in some way makes the cosmos what it is by guaranteeing its boundaries. Yet, here, as with Achilles in the epic, Zeus finds that the decisions he made to serve some larger plot have painful implications. There is a correlation of kinds between Zeus’ loss of Sarpedon and Achilles’ loss of Patroklos. The difference is that Zeus understands the promise he has made.

Schol. T ad Hom. Il. 16.433-8a1

“Don’t criticize the poet for this: for it is right to show the gods’ sympathy for men and that he speaks the following to her. In addition, Zeus’ mourning is didactic: the poet shows that even the gods submit to what is fated. It is therefore correct for human beings to bear fate nobly”

οὐ μεμπτέον τὸν ποιητήν· ἢ γὰρ ἀφιέναι δεῖ τὴν συγγένειαν τῶν θεῶν τὴν πρὸς ἀνθρώπους ἢ τὰ ἑπόμενα αὐτῇ λέγειν. ἅμα δὲ καὶ παιδευτικὴ ἡ τοῦ Διὸς ὀλόφυρσις, διδάσκοντος τοῦ ποιητοῦ ὅτι καὶ θεοὶ τῇ εἱμαρμένῃ ἐμμένουσι· δεῖ οὖν καὶ τοὺς ἀνθρώπους τὰς εἱμαρμένας φέρειν γενναίως.

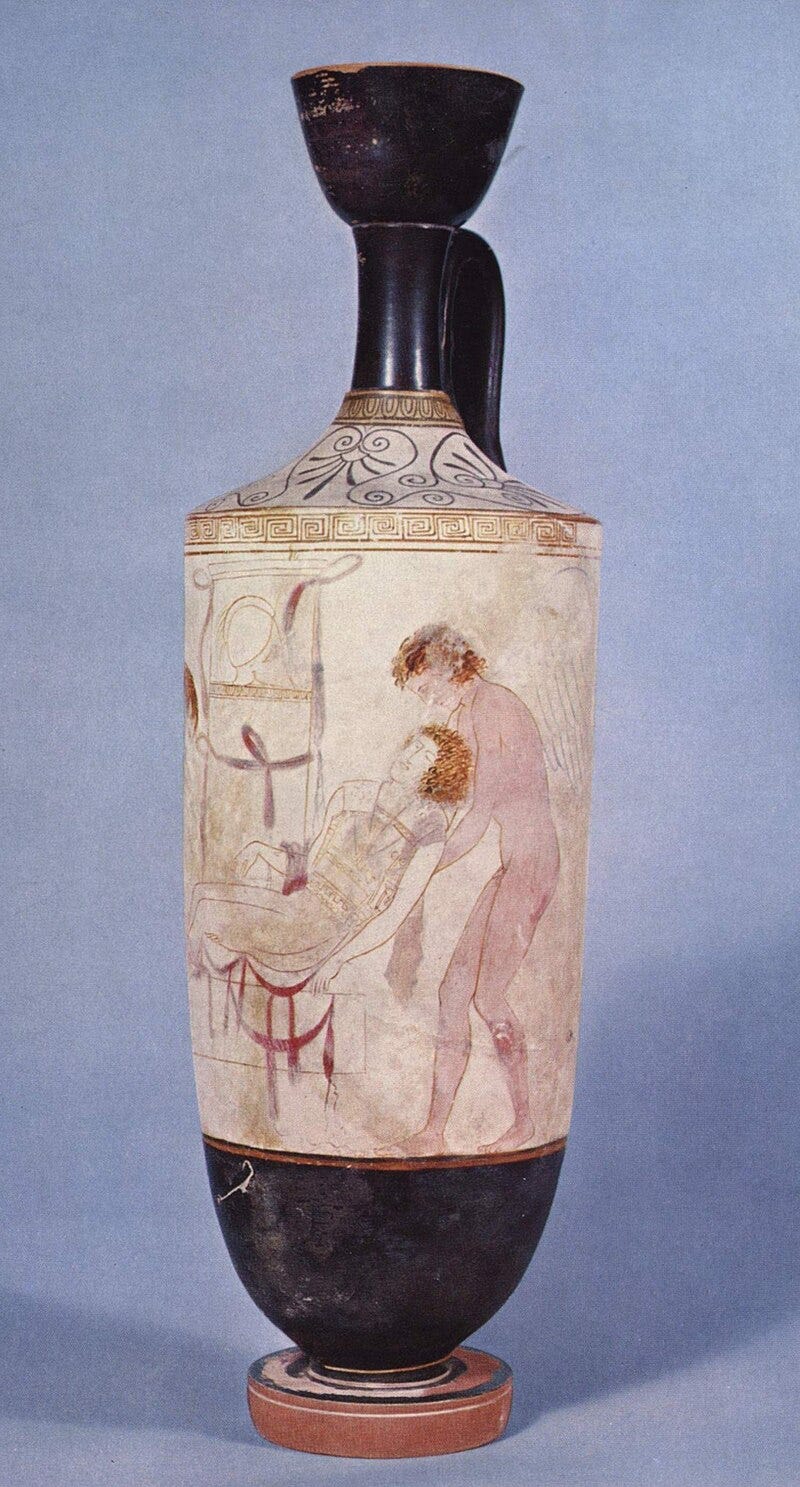

This exchange in the middle of book 16 has two additional ‘metaphysical’ or cosmic concerns. First, it establishes that mortality is an immutable fact of human life. Sarpedon is a good figure to explore this because he is in a way a refraction of Achilles as the hero son of a god who likely received cult worship. Indeed, his death scene is an important piece of repeated iconography in early Greek art and within the Iliad he is a figure who has spoken directly to the connection between being a noble/heroic figure and risking one’s life as a matter of obligation. In addition, Sarpedon’s death comes at a time when the death of Patroklos is anticipated, a death that in multiple ways serves within the Iliad as a surrogate death for Achilles.

The second cosmic effect of Zeus in this book is to emphasize the honors of the dead. As I discuss in an earlier post, the Theogony and the broader epic tradition positions Zeus’ stability in the universe as a feature of his ability to guarantee the social/religious positions of the gods. In a similar way, the Iliad may be seen to offer not just an etiology for human death, but also an explanation for how the dead should be honored and what kind of extra-mortality is available to the best. This is no minor issue for the Iliad which has offered and complicated kleos (immortal glory/fame) as compensation for an early death and which later shows how important it is to bury the dead and present them with the rituals that are necessary for the creation and perpetuation of kleos: funerary lament and, to get meta-poetic with it, perhaps epic itself.

Iliad 16. 439-461

“Then queen, ox-eyed Hera answered him

Most shameful son of Kronos, what kind of a thing have you said.

Do you really want to rescue from discordant death

When it was long ago fated for this man because he is mortal?

Do it. But the rest of the gods will not praise you for it.

I’ll tell you something else, and keep this in your thoughts:

If you send Sarpedon alive to his own home,

Think about how one of the other gods won’t want

To send their dear son free of the oppressive conflict.

For around the great city of Priam there are many sons

Of the immortals fighting, and you will incite rage in those gods.

But if this is ear to you, and your heart does mourn,

Let him stay in the oppressive battle indeed

To be overcome by the hands of Patroklos, Menoitios’ son.

Then when his soul and and his life leaves him,

Have death and sweet sleep take him until

They arrive at the land of broad Lykia.

There, his relatives and friends will bury him

With a tomb and a marker. This is the honor due to the dead.“So she spoke, and the father of men and gods did not disobey her.

He was shedding bloody teardrops to the ground,

Honoring his dear son, the one Patroklos was about to destroy

Far off from his fatherland in fertile Troy.”

In this speech, Hera occupies something of a gendered position: in archaic Greek culture, women are represented as having special associations with death and burials, both in the act of caring for bodies and in the performance of laments (as we see at the end of the Iliad). There is a symbolic/thematic connection between a gendered ability to give life and knowledge about life’s end that is likely connected to Greek mythology. Here, in one of the rare places that Hera provides advice Zeus heeds, it is directly related to clarifying human mortality and establishing ritual practices to honor it.

Later on in the the same book, Zeus repeats part of Hera’s speech to confirm what Sarpedon will receive the rites due to the dead:

Iliad 16.666-676

“And then cloud-gathering Zeus addressed Apollo:

‘Come now, dear Phoebus, cleanse the dark blood

From the wounds, once you get to Sarpedon, and then

Bring him out and wash him much in the river’s flows

And anoint him with ambrosia and put ambrosial clothes around him.

Send him to be carried by those quick heralds,

The twins sleep and death, and have them swiftly

Place him in the rich land of wide Lykia.

There, his relatives and friends will bury him

With a tomb and a marker. This is the honor due to the dead.”

The final phrase in Zeus’ speech “This is the honor due to the dead” (τὸ γὰρ γέρας ἐστὶ θανόντων) occurs again at line 23.9 when Achilles inaugurates Patroklos’ burial before the games in his honor and its substance is central to the debate at the beginning of book 24 about returning Hektor’s body to his family.

Zeus’ suffering for his son creates common ground between gods and mortals over the death’s inevitability for human beings. It foreshadows, or echoes, Thetis’ sorrow for Achilles’ death even as it brings humans and gods together into a cosmos ordered by the fact that Zeus keeps his word. All humans die, but in the universe stabilized by Zeus some rights remain untouchable even in death.

The death of Sarpedon both anticipates future deaths (Patroklos, Hektor and Achilles outside the epic) and also affirms the importance of burial rites for human beings and inscribes them as part of the same system of honors that stabilize the cosmic order. Implicit in this is burial as a universal human right: the Iliad both provides a framework for establishing such an extra-political belief and also anticipates the sense of umbrage that attends other mythical traditions like the failure to bury the dead of the Seven Against Thebes.

A short Bibliography on Sarpedon book 16

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Allen, Nick J.. “Dyaus and Bhīṣma, Zeus and Sarpedon: towards a history of the Indo-European sky god.” Gaia, vol. 8, 2004, pp. 29-36.

Barker, Elton T. E.. “The « Iliad »'s big swoon: a case of innovation within the epic tradition ?.” Trends in Classics, vol. 3, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1-17.

Barker, Elton T. E., and Joel P. Christensen. 2019. Homer's Thebes: Epic Rivalries and the Appropriation of Mythical Pasts. Hellenic Studies Series 84. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Delattre, Charles. “Entre mortalité et immortalité: l'exemple de Sarpédon dans l'« Iliade ».” Revue de Philologie, de Littérature et d’Histoire Anciennes, 3e sér., vol. 80, no. 2, 2006, pp. 259-271.

Gartziou-Tatti, Ariadni. 2023. “Boreas, Hypnos, Thanatos, and the deaths of Sarpedon in the Iliad.” In “Γέρα: Studies in honor of Professor Menelaos Christopoulos,” ed. Athina Papachrysostomou, Andreas P. Antonopoulos, Alexandros-Fotios Mitsis, Fay Papadimitriou, and Panagiota Taktikou, special issue, Classics@ 25. https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:103900170.

Higbie, Carolyn. “Greeks and the forging of Homeric pasts.” Attitudes towards the past in antiquity : creating identities: proceedings of an international conference held at Stockholm University, 15-17 May 2009. Eds. Alroth, Brita and Scheffer, Charlotte. Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis. Stockholm Studies in Classical Archaeology; 14. Stockholm: Stockholm University, 2014. 9-19.

Lateiner, Donald. “Pouring bloody drops (Iliad 16.459): the grief of Zeus.” Colby Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 1, 2002, pp. 42-61.

Marks, J. 2016. “Herding Cats: Zeus, the Other Gods, and the Plot of the Iliad.” In The Gods of Greek hexameter poetry: from the archaic age to late antiquity and beyond, ed. J. J. Clauss, M. Cuypers and A. Kahane, 60–75. Stuttgart.

Nagy, Gregory. “On the death of Sarpedon.” Approaches to Homer. Eds. Rubino, C. A. and Shelmerdine, Cynthia W.. Austin, TX: Univ. of Texas Pr., 1983. 189-217.

Pucci, Pietro. “Banter and banquets for heroic death.” Post-structuralist classics. Ed. Benjamin, Andrew. Warwick stud. in philos. & liter. - . London: Routledge, 1988; New York: 1988. 132-159.

Spivey, Nigel. The Sarpedon krater: the life and afterlife of a Greek vase. Landmark Library. London: Head of Zeus, 2018.

Tsingarida, Athéna. “The death of Sarpedon: workshops and pictorial experiments.” Hermeneutik der Bilder: Beiträge zur Ikonographie und Interpretation griechischer Vasenmalerei. Eds. Schmidt, Stefan and Oakley, John Howard. Beihefte zum Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum; 4. München: Beck, 2009. 135-142.