As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 7, as discussed in the introductory post, can be split into the following subsections: the divine orchestration of the duel, the duel between Hektor and Ajax, assemblies of the Trojans and the Greeks, and the building of the Achaean wall and the divine response. The assemblies in the latter half of the book provide a unique opportunity to compare Greek and Trojan political organizations.

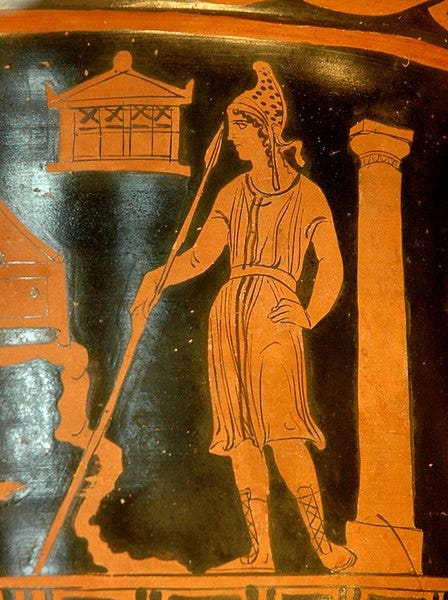

As others have written, the political institutions in the Iliad reflect the basic organization of many Greek city-states: a small, mostly aristocratic/oligarchic council for governing and decision-making, and a larger public assembly for the adjudication of disputes and the performance of political relationships. The three distinct political groups in epic–the Achaeans, Trojans, and the Gods–all provide various versions of these institutions and the ‘success’ of each polity partly hinges on how they work.

Elsewhere, I have outlined the major ‘political’ activities in the Iliad. Apart from the repeated engagement between Poulydamas and Hektor, Antenor’s speech in book 7 is one of the few times the Trojans encounter dissent. The significance of these scenes is often missed between the more famous dual and the divine response to the construction of the Achaean walls.

Antenor is an interesting figure: in a way, he is positioned as something of an equivalent to Nestor. The larger poetic tradition, however, notes that he was known as being friendly to the Greeks and provides some ground for suspicion.

Schol bT Il. 3.205a ex. 1-5

When they were coming out of Tenedos as ambassadors with Menelaos, Antênôr, the son of Hiketaos received them and saved them when they were almost killed through deceit. For this reason, during the sack of Troy, Agamemnon ordered that the household of Antênor be spared, and he signalled this by hanging a leopard’s skin in front of his home.

ὅτε ἐκ Τενέδου ἐπρεσβεύοντο οἱ περὶ Μενέλαον, τότε ᾿Αντήνωρ ὁ ῾Ικετάονος ὑπεδέξατο αὐτούς, καὶ δολοφονεῖσθαι μέλλοντας ἔσωσεν· ὅθεν μετὰ τὴν ἅλωσιν τῆς Τροίας ἐκέλευσεν ᾿Αγαμέμνων φείσασθαι τῶν οἰκείων ᾿Αντήνορος, παρδάλεως δορὰν ἐξάψας πρὸ τῶν οἴκων αὐτοῦ.

Schol. in Il. bT 7.335a ex. 1-4

Another Trojan assembly: for it was necessary to look at what should be done since the sons of the king were being beaten, the city was imperiled by Diomedes and, because of the transgression, they were in dire straits. [as] There was Nestor among the Greeks, the Trojans had Antênor.

Τρώων αὖτ' ἀγορή: ἔδει γὰρ τῶν τοῦ βασιλέως υἱῶν ἡττωμένων καὶ κινδυνευσάσης τῆς πόλεως ὑπὸ Διομήδους, δυσελπίδων ὄντων διὰ τὴν παράβασιν, σκοπεῖν τι τῶν ἀναγκαίων. ἔστι δὲ ἐν τοῖς ῞Ελλησι Νέστωρ, ἐν δὲ Τρωσὶν ᾿Αντήνωρ.

Schol. in Il. bT 7.347a ex. 1-3

Antênor stands among them because he is was a patron of the Greeks, a public speaker, and a god-fearing man. And Hektor was silent because he is ashamed to end the war, lest he appear to be afraid because he was just defeated.

ex. τοῖσιν δ' ᾿Αντήνωρ: ὡς πρόξενος ῾Ελλήνων καὶ δημηγορῶν καὶ θεοσεβής. ῞Εκτωρ δὲ σιωπᾷ αἰσχυνόμενος διαλύειν τὴν μάχην, ἵνα μὴ δοκῇ δεδοικέναι διὰ τὸ νεωστὶ ἡττῆσθαι.

What I find most interesting in the scenes that follow is how Priam is forced to accommodate Antenor’s dissent alongside Paris’ recalcitrance. Of course, Antenor’s suggestion to return Helen is against the poetic tradition and ultimately possible. At some level, there’s no reason for this scene to exist at all, unless it reflects in some way on the themes of this particular version of Achilles’ rage. As I argue in an article from a few years back, the exchanges in book 7 function as an index of the “limits on advice and deliberation” in the Trojan polity.

In the sequences of speeches below, note how Priam attempts to acknowledge the ‘plans’ of both speakers and then directs the herald Idaios to take the complex messages to the Achaeans. Rather than delivering Priam’s speech verbatim, Idaios modifies it, especially in the delivery of Paris’ proposals.

Opening of the Trojan Assembly, 7.345-353

Then the Trojan assembly was held on the city peak of Ilium,

terribly disordered, alongside the doorways of Priam’s home.

Among them prudent Antenor began to speak publicly:

‘Hear me Trojans, Dardanians, and allies

so that I may speak what the heart in my chest bids.

Come now, let us give Argive Helen and her possessions too,

to the sons of Atreus to take away; now we fight

even though we made false the sacred oaths; thus I do not expect

that anything advantageous for us will happen unless we do this.’

Paris’ Response, 7.354-64

‘Antenor, no longer do you speak these things dear to me—

you know how to think up yet another mûthos better than this.

If you say this truthfully in public and earnestly indeed,

then the gods themselves have surely already obliterated your wits.

But I will speak out publicly among the horse-taming Trojans:

I refuse this straight-out; I will not hand over the woman;

but, however many things I took from Argos to our home

I am willing to give them back and to add other things from my household.’

Priam’s Intervention, 7.365-79

And saying this he [Paris] sat down and among them rose

Dardanian Priam, a counselor equal to the gods—

well-intentioned towards them he spoke publicly and spoke among them:

‘Hear me Trojans and Dardanians and allies

so that I may say those things the heart in my chest bids.

Now, take your dinner throughout the city as you have before

and be mindful of the watch and keep each other awake.

At dawn let Idaios go to the curved ships

to repeat the plan of Alexandros, on whose account this conflict has arisen,

to Atreus’ sons, Agamemnon and Menelaos—

and also to propose this wise plan, if they wish

to stop the ill-sounding war until we have burned the corpses;

we will fight again later until the god separates us

and grants victory to one side at least.’

So he spoke and they all heard him and obeyed.

Idaios’ Report to the Achaians, 7.382-398

[Idaios] found the Danaans, Ares’ followers, in assembly

by the prow of Agamemnon’s ship. Then standing among them

in the middle the loud-voiced herald spoke:‘Sons of Atreus and the rest of the best of all the Achaians,

Priam and the rest of the illustrious Trojans bid me

to speak, in the hope that it might be dear and sweet to you,

the múthos of Alexandros, on whose account this conflict has arisen:

However many possessions he took in the hollow ships

to Troy—I wish he had perished before that—

all those things he is willing to return and to add others from his household.

But the wedded-wife of glorious Menelaos

he says he will not give back—although the Trojans ask him to.

And they also ordered me to speak a speech—if you wish

to stop the ill-sounding war until we have cremated the corpses;

we will fight again later until the god separates us

and grants victory to one side at least.’

In a blend of original message and framing for his audience that is similar to Iris’ speeches to Poseidon in book 15 of the epic, Idaios reveals internal dissent about Paris’ stance. Such subtlety rings of a political realism, despite the heroic nature of epic. The suffering of the city and its people is laid at the feet of a selfish prince and a political organization incapable of restraining him.

On Homeric (and Trojan) politics

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know. Follow-up posts will address kleos and Trojan politics

Barker, Elton T. E. “Achilles’ Last Stand: Institutionalising Dissent in Homer’s Iliad.” PCPS 50 (2004) 92-120.

—,—. Entering the Agôn: Dissent and Authority in Homer, Historiography and Tragedy. Oxford, 2009.

Christensen, Joel P.. “Trojan politics and the assemblies of Iliad 7.” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, vol. 55, no. 1, 2015, pp. 25-51.

Clay, J. S. Homer’s Trojan Theater: Space, Vision and Memory in the Iliad (Cambridge, 2011)

Donlan, Walter. “The Structure of Authority in the Iliad.” Arethusa 12 (1979) 51-70.

—,—. “The Relations of Power in the Pre-State and Early State Polities.” In The Development of the Polis in Archaic Greece. Lynette Mitchell and P. J. Rhodes (eds.). London, 1997, 39-48.

Elmer, David. The Poetics of Consent: Collective Decision Making and the Iliad. Baltimore, 2013.

Esperman, L. 1980. Antenor, Theano, Antenoriden: Ihre Person und Bedeutung in der Ilias. Meisen Heim am Glam.

Hall, Jonathan M. “Polis, Community, and Ethnic Identity.” In H. A. Shapiro (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007: 40-60.

Hammer, Dean. “‘Who Shall Readily Obey?” Authority and Politics in the Iliad.” Phoenix 51 (1997) 1-24.

—,—. “The Politics of the Iliad.” CJ (1998a) 1-30.

—,—. “Homer, Tyranny, and Democracy.” GRBS 39 (1998b) 331-360.

—,—. The Iliad as Politics: The Performance of Political Thought. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002.

Létoublon, Françoise. “Le bon orateur et le génie selon Anténor dans l' Iliade : Ménélas et Ulysse.” in Jean-Michel Galy and Antoine Thivel (eds.). La Rhétorique Grecque. Actes du colloque «Octave Navarre»: troisième colloque international sur la pensée antique organisé par le CRHI (Centre de recherches sur l'histoire des idées) les 17, 18 et 19 décembre 1992. Nice: Publications de la Faculté des Lettres, Arts et Sciences Humaines de Nice, 1994, 29-40.

Lohmann, Dieter. Die Komposition der Reden in der Ilias. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1970

Mackie, Hillary. Talking Trojan: Speech and Community in the Iliad . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1996.

Raaflaub, Kurt A., Josiah Ober, and Robert W. Wallace. Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

—,—. “Homer and the Beginning of Political Thought in Greece.” Proceedings in the Boston Area Colloquium Series in Ancient Philosophy 4 (1988) 1-25.

Redfield, James. Nature and Culture in the Iliad: The Tragedy of Hektor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975.

Sale, William M. “The Government of Troy: Politics in the Iliad. GRBS 35 (1994) 5-102.

Schulz, Fabian. Die homerischen Räte und die spartanische Gerusie. Berlin: Wellem, 2011.

Scodel, Ruth. Listening to Homer: Tradition, Narrative and Audience. Ann Arbor: University of

Sealey, R. “Probouleusis and the Sovereign Assembly.” CSCA 2 (1969) 247-69.