Helen ‘appears' for the first time in the Iliad in book 3. What does she look like?

A few years ago there was a bit of a to-do about the ethnicity of Homeric heroes. While some sketchy applications of DNA testing are eager to establish continuity between the people of antiquity and modern populations, others rightly argue that so many of our ideas about race, color, and identity have little to do with the ancient world and everything to do with our own. (See also the discussion on Pharos.)

Within this debate is the important realization that ancient concepts of hue and color-representation may have been altogether different from our own. In addition to Tim Whitmarsh’s essay (cited above), Maria Michel Sassi’s essay does well to explore gaps between how we conceive of color and how the ancients may have.

But questions about DNA and color concepts are separate issues from myth and epic. Sure, the images and values of the ‘real’ world shape fantasy, but there is no direct accord cross-culturally between what people look like and how they imagine their heroes. Consider, e.g., the over-representation of blonde characters in American media in comparison to actual culture or the difference in skin tones in Bollywood from the general population. Racism and colorism shape representation, rendering the reality of genetics and appearance less important than the grammar of idealized bodies.

How did the Greeks imagine their heroes? This is nearly unsolvable because who the Greeks are and what their heroes do for them changes by time and location. We can start, though by looking at some of the language. Greek poetry describes Helen as xanthê and kuanopis. An insensitive and simplistic reading of these facts might claim that she was “blonde” with “blue eyes”. Not only is the situation far more interesting and complicated than this, but I am pretty sure that even if we accept these two words as applying to Helen they would not be equivalent to the appearance these two terms denote in modern English.

Let’s start with the barest fact. What Helen actually looks like is never stated in Homer. When the Trojans look at her, they say she has the "terrible appearance of goddesses" (αἰνῶς ἀθανάτῃσι θεῇς εἰς ὦπα ἔοικεν). This, of course, is not terribly specific.

Elsewhere, she is “argive Helen, for whom many Achaeans [struggled]” (᾿Αργείην ῾Ελένην, ἧς εἵνεκα πολλοὶ ᾿Αχαιῶν, Il. 2.161) she has “smooth” or “pale/white” arms (῏Ιρις δ' αὖθ' ῾Ελένῃ λευκωλένῳ ἄγγελος ἦλθεν, 3.121), but this likely has to do with a typical depiction of women in Archaic Greece (they are lighter in tone than men because they don’t work outside) or because of women’s clothing (arms may have been visible). Beyond that? In the Odyssey, she has “beautiful hair” (῾Ελένης πάρα καλλικόμοιο, 15.58) and a long robe (τανύπεπλος, 4.305).

If anyone is looking for a hint of the ideal of beauty from the legend who launched a thousand ships, they will be sorely disappointed. Why? I think the answer to this partly has to do with the nature of Homeric poetry and with good art in general. Homeric poetry developed over a long duration of time and appealed to many different peoples. To over-determine Helen’s beauty by describing it would necessarily adhere to some standards of beauty while alienating others.

In addition, why describe her beauty at all when the audience members themselves can craft an ideal in their mind? As a student of mine said while I mused over this, Helen “cannot have descriptors because she is a floating signifier”. She is a blank symbol for desire upon which all audience members (ancient and modern, male and female) project their own (often ambiguous) notions of beauty. To stay with the ancient world, think of that seminal first stanza in Sappho fr. 16:

Some say a force of horsemen, some say infantry

and others say a fleet of ships is the loveliest

thing on the dark earth, but I say it is

[whatever] you loveΟἰ μὲν ἰππήων στρότον, οἰ δὲ πέσδων,

οἰ δὲ νάων φαῖσ’ ἐπὶ γᾶν μέλαιναν

ἔμμεναι κάλλιστον, ἐγὼ δὲ κῆν’ ὄτ-

τω τις ἔραται

As long as beauty is relative and in the eye of the beholder, any time we disambiguate it by saying that it is one thing and not another we depart from an abstract timeless idea and create something more bounded and less open to audience engagement. I think that part of what makes Homeric poetry work so well is that it combines a maximum amount of specificity within a maximized amount of ambiguity.

Outside of Homer, Helen is described with a little more detail, but in each case the significance of the signifier is less than it appears. In Hesiod, she has nice hair again (῾Ελένης ἕνεκ' ἠυκόμοιο, Works and Days 165; this is repeated a lot in the fragmentary Hesiodic Catalogue). In fr. 9 of the Cypria she is merely a “Wonder for mortals” (θαῦμα βροτοῖσι·). Much later she has “spiraling eyebrows/lashes” (῾Ελένης ἑλικοβλεφάροιο, Quintus Smyrnaeus, 13.470). (N.b. there is a scholion glossing heliko- as “dark-eyed” when it is used in the Iliad).

If we want to learn more about Helen, she has additional features outside of epic poetry in lyric. I would be bold enough to claim that the more personal and erotic character of the genre is a better explanation for this specificity than anything else.

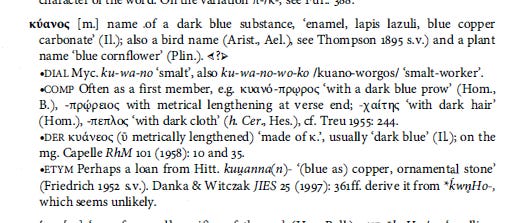

In lyric (e.g. Mesomedes, κυανῶπι θεά, θύγατερ Δίκας,) Helen is “cyan-eyed”, but if we look at the semantic range of this nominal root—which describes dark stones and eyes of water divinities—I think we can argue fairly that this indicates a dark and shiny, even watery texture (like lapis lazuli). I suspect this is about the sheen of eyes rather than their hue.

Eustathius remarks that the epithet κυανώπιδα is common (κατὰ κοινὸν ἐπίθετον) and is often used for dark sea creatures, describing as well his hair (Ποσειδῶνα κυανοχαίτην, Ad Hom. Il 1.555.23). Indeed, nymphs in general are “dark-eyed” in lyric (καὶ Νύμφαι κυανώπιδες, Anacr. fr. 12.2) and water deities remain so in Homer (κῦμα μέγα ῥοχθεῖ κυανώπιδος ᾿Αμφιτρίτης, Il. 12.60). Outside of Homer marriageable women also receive this epithet, including Helen’s sister Klytemnestra (Hes. Fr. 23a κού[ρην Τυνδαρέοιο Κλυταιμήσ]τρην κυανῶπ[ιν· cf. fr. 23.27 and for Althaia, 25.14, Elektra (169).

From Robert Beekes. Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Leiden: Brill, 2010

So, in lyric, Helen has dark pools for eyes. But what about her hair? At Sappho fr. 23 Helen is described as “xanthai” ([ ] ξάνθαι δ' ᾿Ελέναι σ' ἐίσ[κ]ην; cf. Stesichorus Fr. S103: [ξ]α̣νθὰ δ' ῾Ελένα̣ π̣ρ[ ; Ibycus, fr. 1a.5: ξα]νθᾶς ῾Ελένας περὶ εἴδει ). But it is important to note that in this context there is a first-person narrator speaking (“I liken you to fair Helen...”). Note as well that there is something formulaic in these lyric lines: the epithet seems to begin the phrase each time.

When it comes to Hair color, xanthus is used in Homer to describe heroes, but not Helen (Menelaos is Xanthus, for example). A byzantine etymological dictionary suggests that the core meaning of this root has something to do with fire (Ξανθὴν, πυῤῥοειδῆ) and argues that the hair “symbolizes the heat and irascibility of the hero” (αἰνίττεται, τὸ θερμὸν καὶ ὀργίλον τοῦ ἥρωος, Etym. Gud, s.v.). But outside the Iliad and Odyssey the adjective is applied to goddesses: both Demeter (H. Dem. 302) and Aphrodite (Soph. fr. 255) are called Xanthê. Modern etymology sees this as anywhere from yellow to brown. But this is altogether relative again. “Light hair” in a group of people who are blond is almost white; among black/brown haired people, light hair can merely be a different shade of brown.

Again, from Beekes 2010:

In the second book of Liu Cixin's "Three Body Problem Trilogy" The Dark Forest, one of the main characters Luo Ji creates an ideal woman to love in his mind and goes so far as to converse with her, to leave his actual girlfriend for her, and then to go on a trip with her. When he consults a psychologist about this, his doctor tells him his is lucky because everyone is in love with an idea--where the rest of the world will inevitably be disillusioned when they realize this, Luo Ji will never suffer this loss.

Trying to make Helen look like an actual person is not only impossible, but it is something which Homeric epic avoids for good reason.

As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.