This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. This post is part of my plan to share new scholarship on Homer. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

When I talk to reasonably well-informed, non-Homerists about Homer (by which, I mean well-read non-academics, or academics who are into literature but not up-to-date with Homer), they typically ask about one of the following scholarly issues from the 20th century.

Have I read Simone Weil’s “The Iliad, or the Poem of Force?”

Have I read Erich Auerbach on Odysseus’ Scar?

Is it true that Homeric characters have no sense of self (or interiority)?

Is it true that Homer didn’t write the Iliad and the Odyssey?

To start with # 2, for Auerbach, Homer’s paratactic (that is, additive, linear, rather than subordinating) style lends itself to the extreme digression of focusing on the story of how Odysseus got his scar at the moment Eurykleia sees it and demonstrates a commitment to the part to the detriment of the whole. This perspective imagines a poetic narrative not in control of itself, growing in whatever direction works at the time, like twisted branches searching for light. (see Egbert Bakker’s discussion and adjustment of this here.)

As a ‘professional Homerist, the other three issues are more grievous for me, because they are harder to answer and are asked/reiterated to such a degree that it is really hard to disabuse people of the idea that (for 1) Weil’s essay is great, but isn’t even .01% of Homeric scholarship on Homer, (for 3), different modes of representation don’t indicate a “primitive” view of the self; and (4), you don’t need authors or writing to complexity and length in art.

While the apparatus of 20th Homeric scholarship in some way or another has addressed all these questions, we have not reached a firm consensus on them all and we have largely not translated what ideas we do have outside of the sphere of classical scholarship (or, in many cases, even outside of Homeric conversations. In addition, so much of what we have accomplished to answer these questions has come from interdisciplinary efforts–when literary theory, linguistics, cognitive science, or other fields change or emerge, there are often new opportunities to think about old problems.

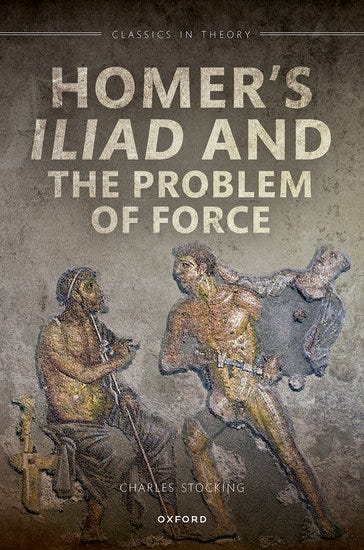

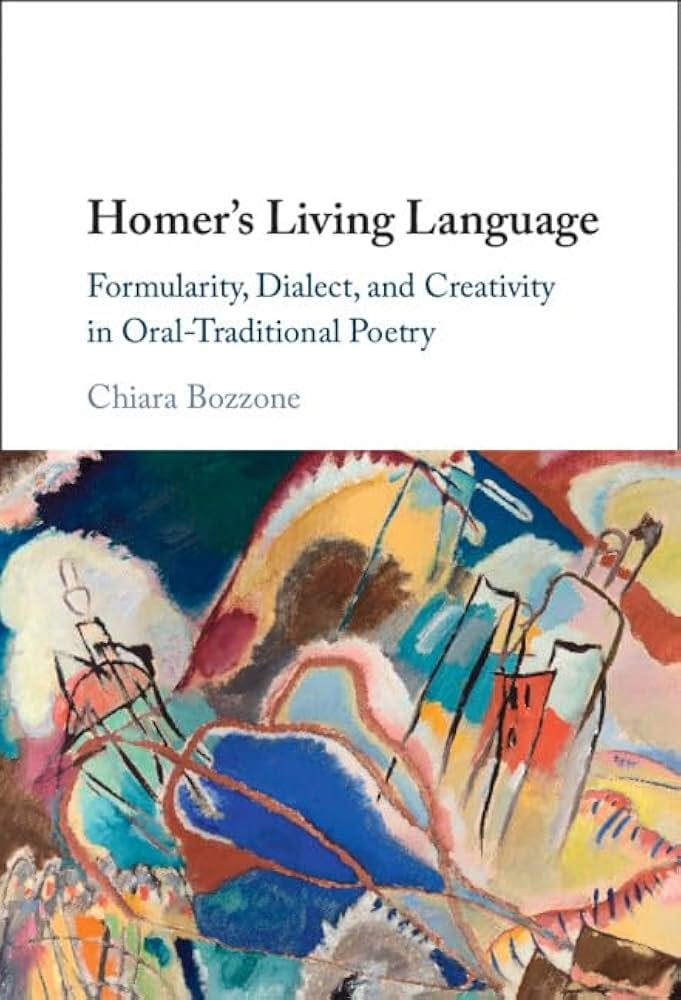

This summer, I am working through two recent books that I think will become standard reading for Homerists and Hellenists: Charles Stocking’s Homer’s Iliad and the Problem of Force(Oxford, 2023) and Chiara Bozzone’s Homer’s Living Language: Formularity, Dialect, and Creativity in Oral Traditional Poetry (Cambridge, 2024). I haven’t finished either, but I wanted to mention them for future posts.

Stocking’s Homer’s Iliad and the Problem of Force starts out by invoking both Simone Weil’s articulation of “force” as the subject of the Iliad rending Homeric poetry–in Stocking’s words–“a transhistorical monument to the singularity of force, which transforms the human subject into an object” (2023, 1) and Bruno Snell’s analysis of different forms of force in his famous Die Entdeckung des Geistes (The Discovery of the Mind). Where Weil sets up “force” thematically as a central concern of the epic (and ignores that there are many ways to talk about it), Snell sees the varied expressions for ‘force’ in Homer (menos, bie, sthenos, kratos, alke, (w)is, dynamis etc) as evidence of an externalization of motivation and agency in Homeric characters. For Snell, according to Stocking, “the plurality of forces parallels [Snell’s] other observations on the plurality of sight and cognition….[which] are symptomatic of a “primitive” form of “self-consciousness” which is not yet capable of unifying “self-conscious thought…[playing] a critical role in Snell’s overall argument that “Homeric man” is incapable of understanding himself as a single, unified individual, neither in body nor mind” (2023, 3).

What Stocking is getting at in his introduction, is that Snell uses the multiple words for force and their applications in epic to argue that Homer depicts people as subject to a number of external powers in a fragmentary way that implies they are incapable of imagining themselves as singular wholes. This argument–connected to a rather particular mid-century, European model of human development that is radically out of step with modern physical anthropology, human cognition, and more, was extremely influential in the 20th century. The most egregious–and amusing–example of an author taking Snell very, very seriously is Julian Jaynes in his The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (his use of Greek material is not good).

[As an aside, I read Weil, Snell, and Jaynes as an undergraduate in 1999 and I don’t think I have ever been the same.]

While I am personally less aggrieved by Simone Weil’s approach, Stocking’s book does an excellent job both of contextualizing her argument and suggesting why we need to examine the approach of both authors further. Stocking leans heavily on linguistics and the inheritors of structural theory, working with less well known approaches to force from Émile Benveniste, Jacques Derrida, and Michel Foucault. Despite bringing together so many heady authors, Stocking does a really good job of providing intellectual histories and summarizing their contributions so that nearly any reader can keep up with the argument.

The stake in Stocking’s argument, for me, is that neither Weil nor Snell take Homeric characters as independent from the powers that govern them, as capable in some way of altering the world around them, of making choices as subjects rather than things that are acted upon. Stocking’s method–to generalize it overmuch–is to do the philological work of analyzing the contextual meaning of all those ways of talking about force and then to see how these possible meanings reflect on our interpretation of the whole Iliad. As a result, there’s a lot of close reading of passages and discussion of linguistics, philosophy, and epic language.

I have written at length about the sense of agency in Homer’s Odyssey, casting the question as one of a dynamic dialogue about determinism and in finishing Stocking’s book, I am going to be looking to see if his explanation for the plurality of ideas about force is one of an absorption of different cultural perspectives on human agency and cognition, an invitation to think about the balance of human will and divine action, or some combination between. This is the kind of book where the details of individual line readings might drive people crazy, but that the overall picture is persuasive, and important. I might end up not liking some of this house’s decor, but I suspect I will admire its foundations and layout for years to come. The first chapter has already made me worry that I was completely wrong about Nestor in my dissertation.

One of the most difficult things about explaining to people why it really doesn’t matter who composed the Iliad or the Odyssey or when writing was introduced into their textualization, is that fully comprehending oral-formulaic theory requires a familiarity with linguistics and Homeric language that is increasingly harder to gain. And, unfortunately, many people who gain expertise in one or the other end up with calcified ideas about language and literature that makes it harder to take that leap of faith needed to let go of prior assumptions. There have been a handful of books that have done this well– I would probably suggest anyone start with Albert Lord’s The Singer of Tales, John Miles Foley’s How to Read and Oral Poem, and Casey Dué’s Achilles Unbound as a good starting points, but Walter Ong’s Orality and Literacy and Ruth Finnegan’s Oral Poetry are standards as well.

Chiara Bozzone’s Homer’s Living Language is likely to most important book-length contribution to oral-formulaic theory since Egbert Bakker’s Poetry in Speech: Orality and Homeric Discourse. This is a big claim, I know, but Bakker really capped over two generations of theorizing through linguistics, comparative approaches, and internal analysis to flesh out (and improve) the approaches to Homeric trail-blazed by Milman Parry and Albert Lord. Bozzone is similar to Bakker in that she adapts cutting-edge (for classicists) linguistic and cognitive theory to help us understand the form of Homeric language and its function.

Bozzone argues that Homeric kunstsprache (our term for an artificial language for an art form) is an “adaptive technology” that “emerge[s] in response to the challenges of oral-poetic performance”. In response to a century of hand-wringing over what this means for creativity and “innovation”, Bozzone presents a powerful case that rather than limiting a performer’s freedom, this technology contributes to “the greatness of his art”. In this book, I will be looking for what the singular “poet” means to Bozzone and how the modern scholarship engages with ancient concepts, but already suspect that I will be a fan of the process of discovery Bozzone shares with us. She adduces comparisons from chess and jazz alongside lessons from play-by-play announcers and hip-hop, all while presenting pretty technical and enlightening overviews of Greek dialect and meter. I think some of these chapters are going to make my brain hurt, but it will be a good kind of pain.

Both of these books are exceptionally well researched, written, and polished. I will post tidbits here and there as I work through them.

One of the most difficult things about explaining to people why it really doesn’t matter who composed the Iliad or the Odyssey or when writing was introduced into their textualization, is that fully comprehending oral-formulaic theory requires a familiarity with linguistics and Homeric language that is increasingly harder to gain.

A very good point -- thinking about these epic poems as books analogous to books in our culture is anachronistic. And that includes our ideas about authorship.

Milman Parry, just read it.