Homer’s ‘Set List’: Imagining a Performance of the Iliad

Part 3: Analysis, Neoanalysis, and the Set List

This is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations.

This post is part three of three looking more closely at the proposition that our Iliad is made up of a series of songs or ‘episodes’ put together in a monumental performance. The first part looks at some of the internal evidence for performance and provides some historical context. The second part explores how much support there is for this model in the classical period. The third part offers some remarks on how this approach may or may not be different from neoanalysis and begins to sketch out how our Iliad may be broken up into songs or episodes.

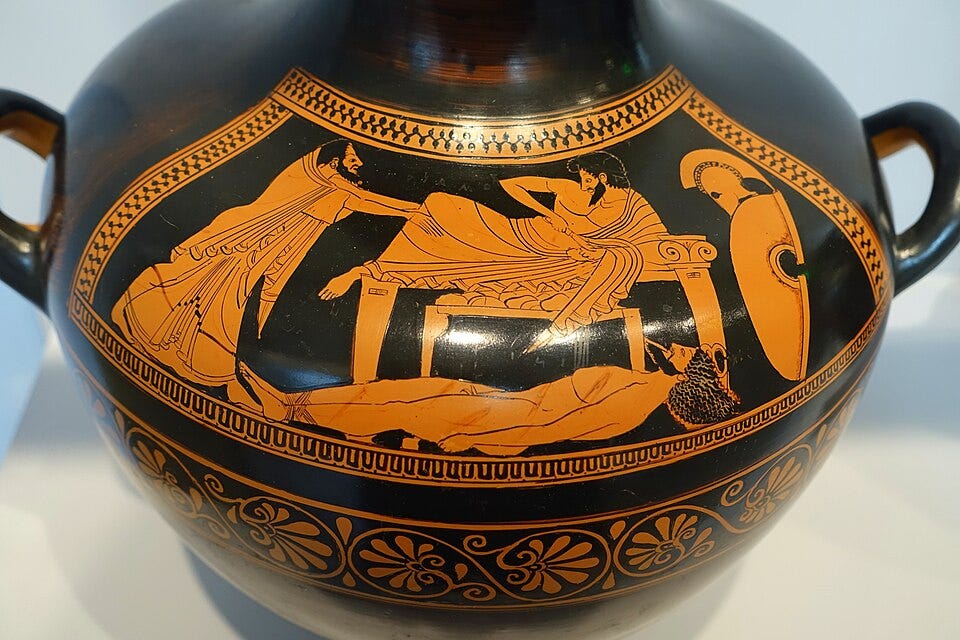

In earlier posts, I have surveyed some internal evidence for episodic composition of the Homeric epics and later literary and iconographic support as well. The basic idea is that the epics themselves show smaller songs with recognizable titles or themes at home in the larger arc of the Trojan War potentially combined into narratives of longer duration (as in Odysseus’ tale of his own experiences to the Phaeacians in the Odyssey). Later authors like Aristotle and Aelian start (or continue?) a tradition of talking about the epics as composed of smaller episodes to support this.

I find the model attractive because it can help us understand how multiple performers of Homer could come together for a major event (like the Panathenaia in Athens) and sing longer epics that are like the poems we have from antiquity. Of course, this model does not explain how such performances would lead to our text. In addition, I want to be very clear that I don’t think this process was necessarily one of a majority of fixed songs. Nor do I think it would have occurred once or yielded the epics we have so easily.

Analysis vs. Neoanalysis

I preface this post with those initial caveats because the episodic thought experiment has led to some navel gazing. A question that I struggle to resolve for myself is how the approach I am taking may be differentiated from earlier scholarly frameworks like analysis or neoanalysis. At some level, many of the ideas will seem similar, but there are some contrasting foundational assumptions. Let me try to walk through what I think the differences are and see if they make sense.

Analysis was an approach to Homer that dominated near the end of the 19th century and for the first quarter of the 20th. The Analysts were primarily opposed to Unitarians. The latter group argued for the artistic unity of the Homeric epics against the growing consensus of scholarship in general that the Iliad and the Odyssey as we have them were not the products of a single author (or authors for each poem). Due to stylistic inconsistency, textual variations, and other aesthetic judgments based on the features of more modern literary authors, scholars had established that the epics we have couldn’t possibly be the product of individual minds.

As a response to this, Analysts sought to show how editorial intervention had changed the poems or how various songs had been edited together to create the epics that survived antiquity. Often Analysts were in search of the most “original” or ancient core of either epic and as a result endeavored in part to identify where parts of the epics we have came from. The poems of the so-called epic cycle were often seen as likely sources for sections that were otherwise added or adapted to the core stories of “The Rage of Achilles” and “The Homecoming of Odysseus”. Unitarians labored to show the “artistic unity” of the poems we have against this onslaught. The sheer volume of discrepancies and the lack of ‘scientific rigor’ in the Unitarian approaches rendered their arguments mostly romantic and easily undermined in the face of the ‘evidence’ provided by the Analysts.

The advent of oral-formulaic theory through the work of Milman Parry and Albert Lord and many others shifted the debate radically. In a simplistic summary, oral-formulaic theory countermanded questions about consistency, style, and the difficulty of composition offered by the Analysts in an evidence-based way that appealed to the scientific bent of scholarship coming out of the 19th century. A great deal of Homeric scholarship from the 1930s into the 1970s was engaged either with fleshing out the details of oral-formulaic theory or with coming to terms of how it shifted our notions of authorship, textualization, and transmission.

Neoanalysis eventually emerged as scholars returned to questions of the relationship between our epics and other narrative traditions. Neoanalysis does not generally claim that the epics we have were made up by editing together other narratives, but instead explores how the parts of the Iliad and Odyssey that we have may have drawn on other poems (or poetic traditions) such as the Aithiopis or the Kypria. This approach has been pretty fruitful in showing how our epics draw on motifs, plots, and scenes that we believe were in other lost poems. But often, neoanalytic claims betray older analytic motivations. Erwin Cook summarizes some of these tensions well in his work on Iliad 8:

“Analytic scholars such as Wilamowitz used the episode to support their argument that Book 8 was “late” because it echoes accounts based on the Aithiopis in which Nestor again suffers a chariot wreck, and his son, Antilokhos, rescues him at the cost of his own life.9 An assumption underlying this argument is that one account is “imitating” the other. The derivative account is inherently “inferior” to its model, and betrays its dependency in part by its aesthetic shortcomings, including its imperfect integration into the narrative. For example, the Neoanalyst Wolfgang Kullmann accepts Analytic claims about the relative priority of the two episodes, though he avoids the Analytic conclusion that the Iliadic passage is interpolated by arguing that the Aithiopis is earlier than the Iliad.”

My reservations about Neoanalysis have generally been (1) that the approach too often assumes that the Iliad or Odyssey are drawing on poems that were prior to them (therefore in some way more original and authentic) and (2) that a great deal of the evidence we have for the contents or even existence of these poems comes from scholarship that developed to explicate the Iliad and the Odyssey. There’s an essential circularity to claiming that the Homeric epics are based on material that only ended up being preserved in reference to the Iliad or the Odyssey. If we imagine epic performance as lasting hundreds of years in many different contexts, it seems tenuous to me to make significant compositional claims based on secondary evidence when many thousands of other performances may have helped shape their character. In addition to this concern for circularity, I think the hierarchical models favored by such approaches tend to create stemmata and trees that look like manuscript traditions and not the flowing and circulating of motifs, ideas, and structures that could make it very likely for a song we imagine as late to have actually influenced something we conceive as earlier while they were both in the process of developing into their final forms. (And to add more apprehension to this: the very notion of a final form is ill-fit to composition in performance.)

Episodicism (?)

Overall, it should be clear that I am not fundamentally opposed to the notion that the epics we have integrate material that existed prior to their final performances and textualization. My basic contention is that we cannot really know anything other than the poems we have and it is more fruitful to imagine that even if we have an Iliad that was influenced by an Aethiopis, each of the story traditions that these poems represent went through innumerable iterations that influenced each other. As a result, pointing to a scene in our Iliad and claiming it was based on a specific scene in a specific poem thoroughly misconstrues the nature of oral-derived poetry. (Many Neoanalysts are certainly proponents for the orality of the Homeric epics, of course.)

Given these distinctions, then, how is imagining our epic poem coming together through the performance of discrete episodes related to Neoanalysis? Some of the assumptions are certainly the same, namely that there were more or less fixed story traditions within the Trojan War narrative myth and that these traditions were recognizable to audiences.

I believe that this approach is different in two basic ways. First, I am exploring how the Iliad is made up of smaller parts to explain its compositional unity and not assuming the priority of any given part over another. Second, I am not proposing that the individual episodes are fixed and portable objects, but rather different song traditions with recognizable features that could be performed independently of the whole if needed. Unlike the Analysts, I am not proposing that there is a core and original Iliad that this process will be able to identify. Unlike some Neoanalysts, I am not trying to reconstruct how the Iliad was based on or made up of earlier poems. Instead, I am trying to imagine what it might look like over time to have a more or less regular list of episodes that could be performed as part of a larger performance. Karol Zieliński (2023, 664) presents a somewhat stronger articulation:

“If, as we have already demonstrated, the songs of the cycle showed a given episode in the context of the whole Trojan War, then it follows that they must have retained a certain degree of independence. The presentation of these episodes in sequence must have taken place on special occasions, e.g. during great festivals like the Panathenaia. But the independence of a song depicting a given episode from the perspective of the whole war could have been possible only because the thematic range of the cycle had already been established and familiar, so it seems that the principle of sequential presentation is deeply rooted in Greek tradition.”

(I must also confess to worrying that the distinction I am attempting to draw is too fine to be a difference that makes a difference. There are many different shades of Neoanalysis. This approach certainly contrasts with that of Martin West in The Making of the Iliad where he sees the integration of different narrative traditions as a very writerly pursuit. But there would be far less tension with the work of scholars like Christos Tsagalis whose approach is more flexible and in tune with oral traditional theory).

Here again, I think the Apologoi—books 9-12 of the Odyssey—can provide an instructive example. Imagine Odysseus’ audience in Skheria: they have no notion of Odysseus’ tale as a series of discrete episodes that may have had an independent existence in different story traditions. Instead, they experience a coherent narrative with many turns, all functioning in the service of explaining how Odysseus ended up on their island. The parts have different length and importance: the Cyclops episode and the Nekyia are longer and much more detailed than the tale of Aeolus or the Lotus-eaters. Circe’s island presents a beginning, middle, and end that is much more well-developed than the brief tales of the Laistrygonians or the Kikones. But they are connected through the narrative conceit of sea-faring in a way that renders them separate even as part of a whole. At the same time, they are thematically connected to the epic as a whole: the scenes end with the deaths of Odysseus’ men after they eat the cattle of the sun (anticipated by the proem in Odyssey 1) and Odysseus swept up on Calypso’s island, where the external audience finds him in Odyssey 5.

Now imagine the 10 scenes of the Apologoi as a set list in a live performance. It would take very little effort for a seasoned group of performers to musically “sample” or anticipate parts of the 9th and 10th songs at the beginning of the set. The songs could be blended together smoothly or abruptly as the performance required, giving the sense of functioning as a single composition even when the individual songs may have come from different places. In the context of one performance, moreover, the musicians might adapt the songs to fit one another in a way they might not if they were performed in a different order or individually.

The Iliadic Set List

I have spent a good deal of time talking about the idea. Now it is time to make it a little more concrete and see what comes of it. I have reached out to a few friends to help explore methods for testing this, both quantitative (using statistical language modeling) and qualitative (thinking about thematic and artistic aspects). I am also trying to figure out how to use analogical methods too: to really think about how modern professional musicians “stitch” their performances together.

For now, here’s a list of the books of the Iliad and the episodes we have some reason to believe would have been identifiable in antiquity, based on evidence in ancient literature, art, and scholarship.

Book || “episode/Song”

1 Overarching: Rage of Achilles + Ransoming of Briseis + Strife of Agamemnon and Achilles

2 False Dream +Thersites +Catalog of Ships

3 Teichoskopia + Duel of Menelaos and Paris + Helen and Paris in the Bedroom

4 Oath Breaking (Pandaros) +Epipolesis

5 +Diomedea / Aristeia of Diomedes +Wounding of Aphrodite + Theomachy

6 Hektor’s Visit to the city + [Glaukos and Diomedes as an independent episode]

7 Duel between Hektor and Ajax

8 Echoes of the Aethiopis

9 Embassy to Achilles

10 Doloneia

11 Aristeia of Agamemnon + Wounding of Diomedes

12 Teikhomakhia

13 Fighting by the Ships/Battle of the ships

14 Dios Apate

15 Echoes of Succession Myths

16 Patrokleia

17 Fight over the body: Menelaos v. Hektor over Euphorbus

18 Arms of Achilles / Shield of Achilles

19 Reconciliation (?); Achilles talks to his horses

20 Aeneas vs. Achilles

21 Theomachy

22 Achilles Kills Hektor + Achilles mutilates the body

23 Achilles kills captives + Contest for Patroklos

24 Ransoming of Hektor + Laments of Hecuba and Andromache

I have italicized a few episodes I want to identify but can’t find good support for.

For me, what is surprising in this list is not so much that there is some support for an episode in nearly every book, but that there is so little support for books 8 and 15, which have been identified by scholars like Bruce Heiden as really important to the structure and themes of our particular Iliad. In addition, even a cursory review of the material shows much that is not accounted for. The greater portion of the episodes identified in antiquity accord with the epic’s first third (where it seems to engage the most with the traditions that precede the war). There’s a compositional echoing of the Odyssey here as well: both epics seem to be more fluid and strange in their second halves than their first. Scenes like Agamemnon’s intervention in the sparing of Adrastus in book 6 may be special to this version of the Iliad and therefore more significant for its interpretation. Political scenes like those in books 1, 2, 9, 19, and the beginning of 24 that people like Elton Barker have shown are crucial for understanding the Iliad’s politics also seem underrepresented in the episodic tradition.

None of this vitiates the thought experiment–instead, I think it provides a really unique chance to reconsider again that dynamic relationship between the Iliad we have and the performance traditions that produced it. Thinking about the relationship between the synchronic moment of that performance and how singers came together to respond to their audiences and their times is one of the things that not only keeps the Iliad alive for me, but keeps its study vital.

Next steps include mapping out the line numbers for the episodes and interstitial parts, doing more research to see if other song traditions have been overlooked, and then taking turns with others working on this process, and pushing through the various frameworks for thinking about this reimagined performance. If you’re reading this and have thoughts, please share them. Like the epics in their composition, their interpretation is something that happens best with many people taking turns.

Bibliography: As Always, not exhaustive. Also, shared bibliography for all three posts.

Beck, Bill. “Lost in the middle : story time and discourse time in the « Iliad ».” Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic, vol. 1, 2017, pp. 46-64. Doi: 10.1163/24688487-00101003

Rinon, Yoav. “« Mise en abyme » and tragic signification in the « Odyssey »: the three songs of Demodocus.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 59, no. 2, 2006, pp. 208-225. Doi: 10.1163/156852506777069673

Beck, Deborah. “The presentation of song in Homer's « Odyssey ».” Orality, literacy and performance in the ancient world, edited by Elizabeth Minchin, Mnemosyne. Supplements; 335. Leiden ; Boston (Mass.): Brill, 2012, pp. 25-53.

Benardete, Seth. “Some Misquotations of Homer in Plato.” Phronesis 8, no. 2 (1963): 173–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4181724.

Broeniman, Clifford. “Demodocus, Odysseus, and the Trojan War in Odyssey 8.” Classical World, vol. 90, no. 1, 1996-1997, pp. 3-14.

Christensen, Joel P. 2020. The Many-Minded Man. Ithaca.

Christensen, Joel P. (2018). The clinical « Odyssey »: Odysseus’s apologoi and narrative therapy. Arethusa, 51(1), 1-31. Doi: 10.1353/are.2018.0000

Collins, Derek Burton. “Improvisation in rhapsodic performance.” Helios, vol. 28, no. 1, 2001, pp. 11-27.

Collins, Derek. 2004. Master of the Game: Competition and Performance in Greek Poetry. Hellenic Studies Series 7. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_CollinsD.Master_of_the_Game.2004.

Combellack, Frederick M. “Homer the Innovator.” Classical Philology 71, no. 1 (1976): 44–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/268517.

Cook, Erwin F. 1995. The Odyssey in Athens. Ithaca.

Cook, Erwin F. “On the ‘Importance’ of Iliad Book 8.” Classical Philology 104, no. 2 (2009): 133–61. https://doi.org/10.1086/605340.

Davies, Malcolm. The « Aethiopis »: neo-neoanalysis reanalyzed. Hellenic Studies; 71., Washington (D. C.): Center for Hellenic Studies, 2016.

Dué, Casey. 2018. Achilles Unbound: Multiformity and Tradition in the Homeric Epics. Hellenic Studies Series 81. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Due.Achilles_Unbound.2018.

Dué, Casey, Susan Lupack, and Robert Lamberton. “Panathenaia.” Chapter. In The Cambridge Guide to Homer, edited by Corinne Ondine Pache, 187–89. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Edmunds, Lowell. “Three short essays on Demodocus’s song of Ares and Aphrodite (Odyssey 8.266-369).” Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic, vol. 4, 2020, pp. 55-71. Doi: 10.1163/24688487-00401003

Edwards, Mark W.. “Neoanalysis and beyond.” Classical Antiquity, vol. IX, 1990, pp. 311-325. Doi: 10.2307/25010933

Haft, Adele J.. “Odysseus' wrath and grief in the Iliad. Agamemnon, the Ithacan king, and the sack of Troy in Books 2, 4, and 14.” The Classical Journal, vol. LXXXV, 1989-1990, pp. 97-114.

Finkelberg, Margalit. “The first song of Demodocus.” Mnemosyne, vol. XL, 1987, pp. 128-132. Doi: 10.1163/156852587X00111

Finkelberg, Margalit. “The sources of Iliad 7.” Colby Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 2, 2002, pp. 151-161.

Gaisser, Julia Haig. “Adaptation of traditional material in the Glaucus-Diomedes episode.” TAPA, vol. C, 1969, pp. 165-176.

González, José M. 2013. The Epic Rhapsode and His Craft: Homeric Performance in a Diachronic Perspective. Hellenic Studies Series 47. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_GonzalezJ.The_Epic_Rhapsode_and_his_Craft.2013.

Heiden, Bruce. “The placement of « book divisions » in the Iliad.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 118, 1998, pp. 68-81. Doi: 10.2307/632231

Herrero de Jáuregui, Miguel. “Priam's catabasis: traces of the epic journey to Hades in Iliad 24.” TAPA, vol. 141, no. 1, 2011, pp. 37-68. Doi: 10.1353/apa.2011.0005

Howes, George Edwin. “Homeric Quotations in Plato and Aristotle.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 6 (1895): 153–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/310358.

Hunter, Richard L.. “The songs of Demodocus: compression and extension in Greek narrative poetry.” Brill's companion to Greek and Latin epyllion and its reception, edited by Manuel Baumbach and Silvio Bär, Brill’s Companions in Classical Studies. Leiden ; Boston (Mass.): Brill, 2012, pp. 83-109.

Kakridis, Johannes Theophanes. “Auch Homer ist in die Lehre gegangen.” Gymnasium, vol. XCIX, 1992, pp. 97-100.

Karanika, Andromache. “Wedding and performance in Homer: a view in the « Teichoskopia ».” Trends in Classics, vol. 5, no. 2, 2013, pp. 208-233.

Kelly, Adrian. “Performance and rivalry: Homer, Odysseus, and Hesiod.” Performance, iconography, reception: studies in honour of Oliver Taplin, edited by Martin Revermann and Peter J. Wilson, Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Pr., 2008, pp. 177-203.

Kullmann, Wolfgang. “Ἡ σύλληψη τῆς Ὀδύσσειας και ἡ μυθικη παράδοση.” Ἐπιστημονικὴ Ἐπετηρὶς τῆς Φιλοσοφικῆς Σχολῆς τοῦ Πανεπιστημίου Ἀθηνῶν, vol. XXV, 1974-1977, pp. 9-29.

Marks, Jim. “Resisting Aristotle : episodes in the Epic cycle.” Tecendo narrativas : unidade e episódio na literatura grega antiga, edited by Christian Werner, Antonio Dourado-Lopes and Erika Werner, São Paulo: Humanitas, FFLCH/USP, 2015, pp. 55-71.

Most, Glenn W. “The Structure and Function of Odysseus’ Apologoi.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 119 (1989): 15–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/284257.

Murray, P.. “Homer and the bard.” Aspects of the epic, edited by Tom Winnifrith, P. Murray and Karl Watts Gransden, New York: St. Martin’s Pr., 1983, pp. 1-15.

Nagy, Gregory. The Best of the Achaeans. 1999. Johns Hopkins. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Best_of_the_Achaeans.1999.

Nagy, Gregory. 2002. Plato's Rhapsody and Homer's Music: The Poetics of the Panathenaic Festival in Classical Athens. Hellenic Studies Series 1. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Platos_Rhapsody_and_Homers_Music.2002.

Nagy, Gregory and Olga M. Davidson. “On the problem of envisioning Homeric composition: some comparative observations.” Philologia Antiqua, vol. 16, 2023, pp. 15-25. Doi: 10.19272/202304601002

Nelson, Thomas J.. “Iphigenia in the « Iliad » and the architecture of Homeric allusion.” TAPA, vol. 152, no. 1, 2022, pp. 55-101. Doi: 10.1353/apa.2022.0007

Nishimura, Yoshiko T.. “The Circe-episodes in the « Odyssey ».” Journal of Classical Studies, vol. 45, 1997, pp. 40-49.

Postlethwaite, Norman. “The duel of Paris and Menelaos and the Teichoskopia in Iliad 3.” Antichthon, vol. XIX, 1985, pp. 1-6.

Rengakos, Antonios (2002). Zur narrativen Funktion der Telemachie. In André Hurst & Françoise Létoublon (Eds.), La mythologie et l'« Odyssée »: hommage à Gabriel Germain : actes du colloque international de Grenoble, 20-22 mai 1999 (pp. 87-98). Droz.

Rinon, Yoav. “« Mise en abyme » and tragic signification in the « Odyssey »: the three songs of Demodocus.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 59, no. 2, 2006, pp. 208-225. Doi: 10.1163/156852506777069673

Roisman, Hanna M.. “« Rhesus »’ allusions to the Homeric Hector.” Hermes, vol. 143, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1-23.

Segal, Charles (1994). Singers, heroes, and gods in the Odyssey. Cornell University Pr.

Sels, Nadia. “The untold death of Laertes: reevaluating Odysseus’s meeting with his father.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 66, no. 2, 2013, pp. 181-205. Doi: 10.1163/156852511X584991

Thomas, Oliver. “Phemius Suite.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 134, 2014, pp. 89-102. Doi: 10.1017/S007542691400007X

Tsagalis, Christos. 2008. The Oral Palimpsest: Exploring Intertextuality in the Homeric Epics. Hellenic Studies Series 29. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_TsagalisC.The_Oral_Palimpsest.2008.

Tsagalis, Christos. "Towards an Oral, Intertextual Neoanalysis" Trends in Classics, vol. 3, no. 2, 2011, pp. 209-244. https://doi.org/10.1515/tcs.2011.011

Wyatt, William F.. “Homeric transitions.” Ἀρχαιογνωσία, vol. 6, 1989-1990, pp. 11-24.

YAMAGATA, NAOKO. “USE OF HOMERIC REFERENCES IN PLATO AND XENOPHON.” The Classical Quarterly 62, no. 1 (2012): 130–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41820000.

Zieliński, Karol. 2023. The Iliad and the Oral Epic Tradition. Hellenic Studies Series 99. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_ZielinskiK.The_Iliad_and_the_Oral_Epic_Tradition.2023.