Homer’s ‘Set List’: Imagining a Performance of the Iliad

Part 1: Singers in Homer and the Panathenaic Rule

This is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations.

This post is part one of three looking more closely at the proposition that our Iliad is made up of a series of songs or ‘episodes’ put together in a monumental performance. The first part looks at some of the internal evidence for performance and provides some historical context. The second part explores how much support there is for this model in the classical period. The third part offers some remarks on how this approach may or may not be different from neoanalysis and begins to sketch out how our Iliad may be broken up into songs or episodes.

One of the suggestions about the composition and textualization of the Homeric poems I have mentioned in a previous post is that the poems we have received from antiquity are somehow made up of shorter songs or episodes. The inspiration for this comes in part from the poems themselves where we don’t find ‘epic’ poets performing songs anywhere near the length of the Iliad or the Odyssey but instead performances that occur during meals–as in Phemios’ song during book 1 of the Odyssey–or other activities, as when Demodokos sings the song of Hephaestus, Ares, and Aphrodite in book 8.

Scholars like Richard Hunter have seen evidence in these performances for the aesthetics and poetics of Homeric epic writ large (see Segal 1994 for the clearest articulation of this). I think Casey Dué puts this well in her Achilles Unbound when she writes (2019, 42):

“There are, moreover, several passages within the poems that depict the performance of epic poetry, such as the performances of Phemios for the suitors in the house of Odysseus and those of Demodokos for the Phaeacians in the house of King Alkinoos. These passages show a bard performing at banquets, often taking requests for various episodes involving well-known heroes. Such passages in the Homeric texts that refer to occasions of performance are fascinating windows into how ancient audiences imagined the creation of epic poetry ”

Others have extended the idea from these performances to Odysseus’ own narration in Odyssey 9-12 (see Beck 2005 for a discussion). Despite broad agreement that there is some relationship between the depiction of singers in the epics themselves and the generation of epic poetry, however, there remains some skepticism that the shorter performances represented in Homer actually correlate in any meaningful way to the Iliad and Odyssey themselves, both because of the length of the latter and the performance context of the former (see especially Murray 1983).

Three of the inset examples we do find–the song of the homecomings of the Achaeans in Odyssey 1, Demodokos’ song of the strife between Achilles and Odysseus or the tale of the Trojan horse in Odyssey 8–provide us mere titles and little else. Even the reported song of Hephaestus’ trapping of Ares and Aphrodite in book 8 is more of a summary than a song itself. Each takes place while people are doing other things: dining and drinking or playing games. Only Odysseus seems to hold his audience in rapt attention.

Nevertheless, despite the difference in length and putative performance contexts, these shorter songs can help us think about the larger compositions. Based on these examples in the Odyssey and the length of the transmitted narrative Homeric hymns such as the Hymns to Demeter, Aphrodite, Apollo, and Hermes, which are between 200 and 500 lines, scholars have often imagined a traditional performance of a ‘Homeric bard’ as being around the length of the shortest books of the Iliad and the Odyssey. For example, Odyssey 6 is the shortest at 331 lines; Iliad 5 is the longest book at 909 lines. The second longest Homeric Hymn, Apollo, is 546 lines, but many believe it is really two older songs put together. The Hymn to Aphrodite, at just under 300 lines, seems like a reasonable analog to the songs presented in the Odyssey.

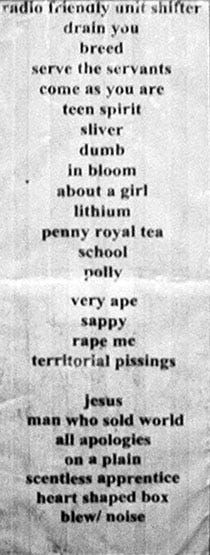

Odysseus’ “Set List”

At a medium pace–c. 5 seconds per line–a 300 line song would probably take about 25 minutes to perform. 25 minutes certainly seems tolerable for a ‘dinner theater’ performance. But the Odyssey may have another model for us too. The story Odysseus tells provides an interesting example because books 9-12 have 2233 lines. Performed at the same pace, this would take a little over three hours (with a slight break after 1473, 11.333 when everyone is silent lasting until 11.378 when Odysseus resumes his take). This is a long tale, but not much more so than the running time of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023, 3 hours).

There’s a certain common sense logic to an argument that follows from these considerations, namely, that the major compositions we have in the Iliad and the Odyssey are likely made up of shorter songs. Indeed, the internal examples of the Odyssey provide some support for this. Those four books are generally split into distinct episodes themselves:

Book 9 (1) the first attack against the Cicones at Ismaros; (2) the Lotus-eaters; (3) the Cyclops scene

Book 10 (4) Aeolus and the bag of the winds, (5) the Laistrygonians and (6) Circe;

Book 11 (7) The Nekyia [in two parts, Catalog of Heroines [Intermezzo]; Catalog of Heroes]

Book 12 (8) Sirens, (9) Skylla and Charybdis, and (10) Helios’ Cattle

(see Most 1989; Cook 1995, 65-80; Christensen 2018 and 2020 Chapter 4 for more on these structures and their functions).

While these episodes vary in length, the average (c. 223 lines) is closer to the shorter of the narrative Homeric Hymns like Aphrodite than it is to the representation of songs by Phemios and Demodokos. What I find even more interesting from this comparison is that several of these scenes are also represented in early Greek art including Odysseus and the Cyclops, the Sirens, and Circe. Evidence from other poetic traditions like the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women also implies that scenes like the Nekyia were traditional too. So, one way of looking at Odysseus’ own story is as a collection of traditional episodes connected together for a specific performance. On a narrative level, of course, it is a series of memories provided by Odysseus to explain how he ended up naked on the shore of Ithaka. But there is no a priori reason that the majority of these scenes unfold in the order they do.

The Panathenaic Rule

The implication from this analysis, of course, is that larger compositions can be brought together from smaller known songs for the right occasion. Such an argument has been bolstered as well by the report of the Panathenaic rule, the only evidence we really have for the monumental performance of the epics in their entirety in antiquity. According to this tradition, rhapsodes would take up singing the Iliad or Odyssey in sequence, picking up where another left off. Additional evidence has suggested that this was a venue where shorter compositions could have been performed to create a corporate whole.

But before pursuing that line of thought, let’s look at some of the evidence for the Panathenaic rule. The first comes from a dialogue ascribed to Plato.

[Plato], Hipparchus 228b–c

Hipparchus was the oldest and the wisest of Peisistratos’ sons. He provided many other wonderful deeds as an indication of his wisdom and was the first to bring Homer’s epics to this country. He compelled the rhapsodes at the Panathenaic games to go through them in order (ἐφεξῆς ) and taking turns (ὑπολήψεως), even as they still do now.

῾Ιππάρχῳ, ὃς τῶν Πεισιστράτου παίδωυ ἦν πρεσβύτατος καὶ σοφώτατος, ὃς ἄλλα τε πολλὰ καὶ ἔργα σοφίας ἀπεδείξατο, καὶ τὰ ῾Ομήρου ἔπη πρῶτος ἐκόμισεν εἰς τὴν γῆν ταυτηνί, καὶ ἠνάγκασε τοὺς ῥαψῳδοὺς Παναθηναίοις ἐξ ὑπολήψεως ἐφεξῆς αὐτὰ διιέναι, ὥσπερ νῦν ἔτι οἵδε ποιοῦσι.

A few qualifying remarks. There’s no good reason to believe that the Panathenaic festival–an annual competition for traditional song–was the only context for the performance of epic poetry. Instead, one possibility is that it is the venue that provided the best opportunity to concretize and eventually textualize the epics we have. The basic outline is that there was a state sponsored festival that provided for the performance of Homeric epic by multiple rhapsodes. Note, however, that the passage refers to “Homer’s works” (τὰ ῾Ομήρου ἔπη) rather than the Iliad and Odyssey in general.

There’s also some debate about how to translate the words I render as “taking turns” and “in order”. There are good discussions in works by Derek Collins, Jose Gonzalez, and Gregory Nagy (see the helpful overview in Dué, Lupack, and Lamberton too). Collins (2004) believes that this passage makes it very unlikely that the epics were performed in their entirety at the festival and points to a passage he positions as indicating an older tradition in Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of the Eminent Philosophers

Diogenes Laertius 1.57 = Dieuchidas of Megara FGH 485 F 6

Solon legislated that Homer’s songs be performed by rhapsodes by prompt [ὑποβολῆς] where when the first stopped, the subsequent singer would start.”

τά τε ῾Ομήρου ἐξ ὑποβολῆς γέγραφε ῥαψῳδεῖσθαι, οἶον ὅπου ὁ πρῶτος ἔληξεν, ἐκεῖθεν ἄρχεσθαι τὸν ἐχόμενον.

Here we have another traditional lawmaker establishing the performance of Homer by rhapsodes (again, note the generic nature of τά τε ῾Ομήρου) as part of an annual festival sponsored by the city. As Nagy has explored, there is an etymological felicity in the name rhapsode for the creation of a larger composition from individual songs. He has reconstructed the meaning as “one who stitches the songs together”. Nagy (2002) translates ἐξ ὑποβολῆς “by relay” instead of “prompt” for some good reasons he elaborates. I am less concerned about the precision of translation for either passage than what I think both passages indicate: a practice of multiple singers taking turns performing Homeric songs in some kind of an order.

It is not clear, as I mentioned above, that the resulting performance had to be our Iliad or Odyssey. There’s also no good reason to assume that what each rhapsode performed was a fixed song. Indeed, Collins believes that there was plenty of room for rhapsodic improvisation and Nagy argues as part of his evolutionary model for the textualization of the Homeric epics that the fixity of the songs changed over time. What I would like to imagine is a flexibility between the two possibilities: that songs that were in some way recognizably Homeric had to be performed but that rhapsodes were expected to embellish and connect them in different ways.

Bibliography: As Always, not exhaustive. Also, shared bibliography for all three posts.

Beck, Bill. “Lost in the middle : story time and discourse time in the « Iliad ».” Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic, vol. 1, 2017, pp. 46-64. Doi: 10.1163/24688487-00101003

Rinon, Yoav. “« Mise en abyme » and tragic signification in the « Odyssey »: the three songs of Demodocus.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 59, no. 2, 2006, pp. 208-225. Doi: 10.1163/156852506777069673

Beck, Deborah. “The presentation of song in Homer's « Odyssey ».” Orality, literacy and performance in the ancient world, edited by Elizabeth Minchin, Mnemosyne. Supplements; 335. Leiden ; Boston (Mass.): Brill, 2012, pp. 25-53.

Benardete, Seth. “Some Misquotations of Homer in Plato.” Phronesis 8, no. 2 (1963): 173–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4181724.

Broeniman, Clifford. “Demodocus, Odysseus, and the Trojan War in Odyssey 8.” Classical World, vol. 90, no. 1, 1996-1997, pp. 3-14.

Christensen, Joel P. 2020. The Many-Minded Man. Ithaca.

Christensen, Joel P. (2018). The clinical « Odyssey »: Odysseus’s apologoi and narrative therapy. Arethusa, 51(1), 1-31. Doi: 10.1353/are.2018.0000

Collins, Derek Burton. “Improvisation in rhapsodic performance.” Helios, vol. 28, no. 1, 2001, pp. 11-27.

Collins, Derek. 2004. Master of the Game: Competition and Performance in Greek Poetry. Hellenic Studies Series 7. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_CollinsD.Master_of_the_Game.2004.

Combellack, Frederick M. “Homer the Innovator.” Classical Philology 71, no. 1 (1976): 44–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/268517.

Cook, Erwin F. 1995. The Odyssey in Athens. Ithaca.

Cook, Erwin F. “On the ‘Importance’ of Iliad Book 8.” Classical Philology 104, no. 2 (2009): 133–61. https://doi.org/10.1086/605340.

Davies, Malcolm. The « Aethiopis »: neo-neoanalysis reanalyzed. Hellenic Studies; 71., Washington (D. C.): Center for Hellenic Studies, 2016.

Dué, Casey. 2018. Achilles Unbound: Multiformity and Tradition in the Homeric Epics. Hellenic Studies Series 81. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Due.Achilles_Unbound.2018.

Dué, Casey, Susan Lupack, and Robert Lamberton. “Panathenaia.” Chapter. In The Cambridge Guide to Homer, edited by Corinne Ondine Pache, 187–89. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Edmunds, Lowell. “Three short essays on Demodocus’s song of Ares and Aphrodite (Odyssey 8.266-369).” Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic, vol. 4, 2020, pp. 55-71. Doi: 10.1163/24688487-00401003

Edwards, Mark W.. “Neoanalysis and beyond.” Classical Antiquity, vol. IX, 1990, pp. 311-325. Doi: 10.2307/25010933

Haft, Adele J.. “Odysseus' wrath and grief in the Iliad. Agamemnon, the Ithacan king, and the sack of Troy in Books 2, 4, and 14.” The Classical Journal, vol. LXXXV, 1989-1990, pp. 97-114.

Finkelberg, Margalit. “The first song of Demodocus.” Mnemosyne, vol. XL, 1987, pp. 128-132. Doi: 10.1163/156852587X00111

Finkelberg, Margalit. “The sources of Iliad 7.” Colby Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 2, 2002, pp. 151-161.

Gaisser, Julia Haig. “Adaptation of traditional material in the Glaucus-Diomedes episode.” TAPA, vol. C, 1969, pp. 165-176.

González, José M. 2013. The Epic Rhapsode and His Craft: Homeric Performance in a Diachronic Perspective. Hellenic Studies Series 47. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_GonzalezJ.The_Epic_Rhapsode_and_his_Craft.2013.

Heiden, Bruce. “The placement of « book divisions » in the Iliad.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 118, 1998, pp. 68-81. Doi: 10.2307/632231

Herrero de Jáuregui, Miguel. “Priam's catabasis: traces of the epic journey to Hades in Iliad 24.” TAPA, vol. 141, no. 1, 2011, pp. 37-68. Doi: 10.1353/apa.2011.0005

Howes, George Edwin. “Homeric Quotations in Plato and Aristotle.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 6 (1895): 153–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/310358.

Hunter, Richard L.. “The songs of Demodocus: compression and extension in Greek narrative poetry.” Brill's companion to Greek and Latin epyllion and its reception, edited by Manuel Baumbach and Silvio Bär, Brill’s Companions in Classical Studies. Leiden ; Boston (Mass.): Brill, 2012, pp. 83-109.

Kakridis, Johannes Theophanes. “Auch Homer ist in die Lehre gegangen.” Gymnasium, vol. XCIX, 1992, pp. 97-100.

Karanika, Andromache. “Wedding and performance in Homer: a view in the « Teichoskopia ».” Trends in Classics, vol. 5, no. 2, 2013, pp. 208-233.

Kelly, Adrian. “Performance and rivalry: Homer, Odysseus, and Hesiod.” Performance, iconography, reception: studies in honour of Oliver Taplin, edited by Martin Revermann and Peter J. Wilson, Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Pr., 2008, pp. 177-203.

Kullmann, Wolfgang. “Ἡ σύλληψη τῆς Ὀδύσσειας και ἡ μυθικη παράδοση.” Ἐπιστημονικὴ Ἐπετηρὶς τῆς Φιλοσοφικῆς Σχολῆς τοῦ Πανεπιστημίου Ἀθηνῶν, vol. XXV, 1974-1977, pp. 9-29.

Marks, Jim. “Resisting Aristotle : episodes in the Epic cycle.” Tecendo narrativas : unidade e episódio na literatura grega antiga, edited by Christian Werner, Antonio Dourado-Lopes and Erika Werner, São Paulo: Humanitas, FFLCH/USP, 2015, pp. 55-71.

Most, Glenn W. “The Structure and Function of Odysseus’ Apologoi.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 119 (1989): 15–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/284257.

Murray, P.. “Homer and the bard.” Aspects of the epic, edited by Tom Winnifrith, P. Murray and Karl Watts Gransden, New York: St. Martin’s Pr., 1983, pp. 1-15.

Nagy, Gregory. The Best of the Achaeans. 1999. Johns Hopkins. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Best_of_the_Achaeans.1999.

Nagy, Gregory. 2002. Plato's Rhapsody and Homer's Music: The Poetics of the Panathenaic Festival in Classical Athens. Hellenic Studies Series 1. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Platos_Rhapsody_and_Homers_Music.2002.

Nagy, Gregory and Olga M. Davidson. “On the problem of envisioning Homeric composition: some comparative observations.” Philologia Antiqua, vol. 16, 2023, pp. 15-25. Doi: 10.19272/202304601002

Nelson, Thomas J.. “Iphigenia in the « Iliad » and the architecture of Homeric allusion.” TAPA, vol. 152, no. 1, 2022, pp. 55-101. Doi: 10.1353/apa.2022.0007

Nishimura, Yoshiko T.. “The Circe-episodes in the « Odyssey ».” Journal of Classical Studies, vol. 45, 1997, pp. 40-49.

Postlethwaite, Norman. “The duel of Paris and Menelaos and the Teichoskopia in Iliad 3.” Antichthon, vol. XIX, 1985, pp. 1-6.

Rengakos, Antonios (2002). Zur narrativen Funktion der Telemachie. In André Hurst & Françoise Létoublon (Eds.), La mythologie et l'« Odyssée »: hommage à Gabriel Germain : actes du colloque international de Grenoble, 20-22 mai 1999 (pp. 87-98). Droz.

Rinon, Yoav. “« Mise en abyme » and tragic signification in the « Odyssey »: the three songs of Demodocus.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 59, no. 2, 2006, pp. 208-225. Doi: 10.1163/156852506777069673

Roisman, Hanna M.. “« Rhesus »’ allusions to the Homeric Hector.” Hermes, vol. 143, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1-23.

Segal, Charles (1994). Singers, heroes, and gods in the Odyssey. Cornell University Pr.

Sels, Nadia. “The untold death of Laertes: reevaluating Odysseus’s meeting with his father.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 66, no. 2, 2013, pp. 181-205. Doi: 10.1163/156852511X584991

Thomas, Oliver. “Phemius Suite.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 134, 2014, pp. 89-102. Doi: 10.1017/S007542691400007X

Tsagalis, Christos. 2008. The Oral Palimpsest: Exploring Intertextuality in the Homeric Epics. Hellenic Studies Series 29. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_TsagalisC.The_Oral_Palimpsest.2008.

Tsagalis, Christos. "Towards an Oral, Intertextual Neoanalysis" Trends in Classics, vol. 3, no. 2, 2011, pp. 209-244. https://doi.org/10.1515/tcs.2011.011

Wyatt, William F.. “Homeric transitions.” Ἀρχαιογνωσία, vol. 6, 1989-1990, pp. 11-24.

YAMAGATA, NAOKO. “USE OF HOMERIC REFERENCES IN PLATO AND XENOPHON.” The Classical Quarterly 62, no. 1 (2012): 130–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41820000.

Zieliński, Karol. 2023. The Iliad and the Oral Epic Tradition. Hellenic Studies Series 99. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_ZielinskiK.The_Iliad_and_the_Oral_Epic_Tradition.2023.

this is great stuff!