This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations. I will return to regular Iliad posts next week.

Storylife comes out officially January 14th, but available for pre-order. Here is its amazon page. here is the link to the company doing the audiobook and here is the press page. I am happy to talk about this book in person or over zoom.

What is Storylife?

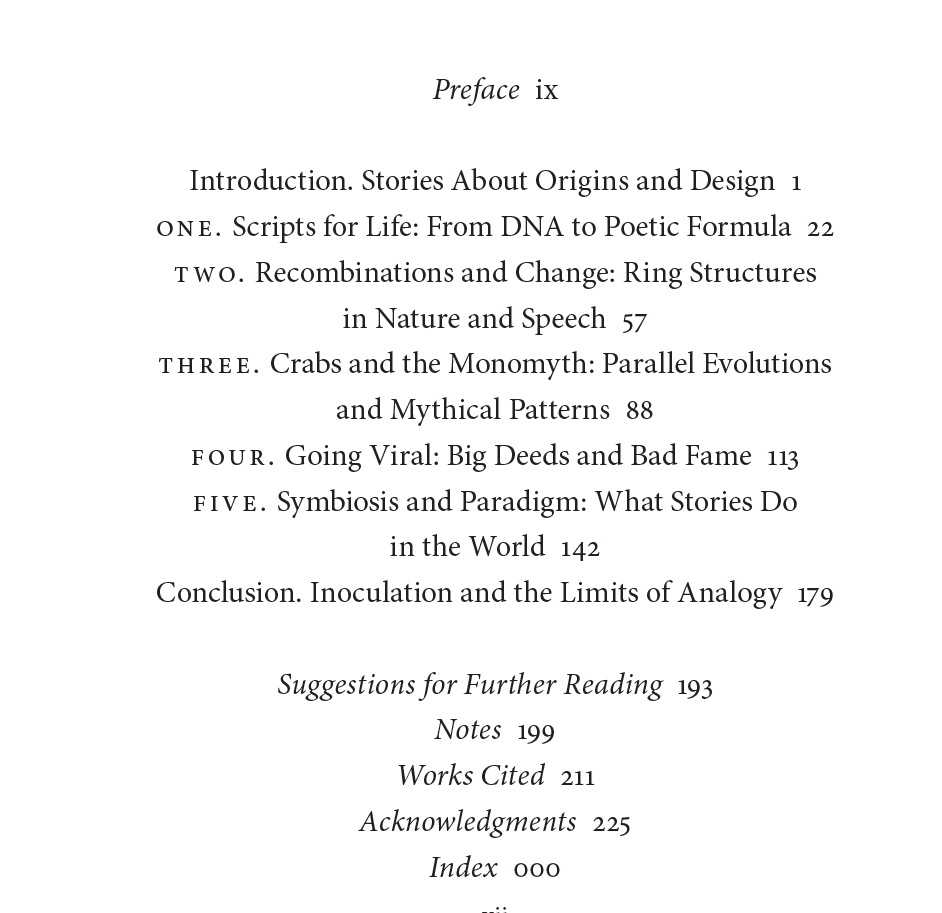

Preface:

“One of the questions I posed to myself before and after writing this book is how I would answer my own children’s (potential) future question: What did I do when the world was ending?”

Storylife applies biological analogies to Homeric poetry and early myth to explore how narrative develops independent of individual human intention and to propose that stories have an agency of their own. It uses the architecture of Homeric language in particular—which is repetitive and often characterized as formulaic—as a case study for how complex structures and thought can develop from smaller structures in a fashion similar to multicellular life. The investigation moves from the structure of language and life to analogies from parasitism and virology to understand the relationship between human communities and the stories they tell. Greek epic and myth provide test cases for how stories change to fit audience ‘ecosystems’ and how their environments are reshaped in turn. Discussions range from parallel narrative evolutions, to viral explosions in ideas, and to the dangerous side of stories in mass shootings and war.

Storylife asks readers to rethink human creativity, the importance of collective actions (and reactions) and the lives we build together with and against narrative. It asks audiences to reconsider how much we control over stories and, in closing, how we should educate ourselves once we acknowledge the power that narrative exerts over us.

From the Conclusion

“The ancient Greek word that gives us poet—poiētēs—is an agent noun from a verb that can mean “make, create, do” (poieō). Poem, also formed from the same root, adds a material suffix -ma to mean a “made thing” or a “creation.” These terms can be translated appropriately in literary senses as “composer” and “composition,” but the side of me that leans toward the mystical also likes thinking of a poet as a maker and poems as worlds, stories as universes waiting for their unveiling.”

Introduction. Stories About Origins and Design

The introduction provides a brief overview of the Homeric Problem and modern concepts of authorship alongside a discussion of teleological misreadings of evolution and human cognition. The discussion touches upon artificial intelligence and the appearance of design, before exploring different metaphors for how narrative like Homeric epic develops and functions in the world: (1) a symphony; (2) a tree in a garden; and (3) a virus, to help us understand how humans and stories evolve alongside one another.

From the introduction:

“This book unfolds as a re-exploration through Homeric poetry of the analogy of narrative and its parts as living (or quasi-living)things…The weak form of my argument is that this analogy helps us understand the complexity of meaning making; the strong form is that narrative has an agency and purpose of its own, and we are merely part of its environment.”

Chapter One. Scripts for Life: From DNA to Poetic Formula

Chapter 1 draws on basic principles of genetics and linguistics to suggest to explore language morphology and semantic meaning. It emphasizes communicative context as an ecosystem that provides epigenetic triggers to shape both narrative form and content. The chapter will invite readers to consider classic problems in Homeric language not as mistakes or errors but instead as examples of vestigial structures. The chapter includes an overview of the digamma in early Greek and a lengthy discussion of the dual forms of the embassy to Achilles in Iliad 9.

From Chapter 1:

“Imagine if we considered the oldest DNA in our bodies to be our authentic character, rather than some element that has persisted over time, contributing in ways we do not always understand to who we are now. This is what it is like when scholars identify “older” parts of Homeric language and attempt to date poems relatively or in some way downgrade and privilege aspects of language by mere comparison. It tells us nothing true about the whole.”

Chapter Two. Recombinations and Change: Ring Structures in Nature and Speech

Chapter 2 considers how the building blocks of life tend to assemble in larger structures. Building on patterns from early multi-cellular life to structures dictated by the laws of physics, this chapter focus in particular on how larger, composite structures in Greek poetry expand on smaller elements, like doublets, triplets, and rings alongside formulae and type scenes. The chapter concludes by suggesting that ring structures offer a compositional reflection of cognitive engagement with narrative, using Sappho fr. 16 and the story of Meleager in the Iliad as examples.

From Chapter 2

“….Ringed structures make propositions, they tell stories, they attempt speech acts such as persuasion and praise. But these rings are also part of the paratactic structure of epic poetry: they accumulate and advance meaning as they progress, and they invite audiences to compare the demarcated part with other sections and the larger whole.”

Chapter Three. Crabs and the Monomyth: Parallel Evolutions and Mythical Patterns

Chapter 3 takes a closer look at how patterns of stories are repeated over time. Through the multiple evolutions of crab morphology, this chapter uses parallel and convergent evolution as analogies to think about narrative repetitions and similarities. The discussion focuses first on Joseph Campbell’s “monomyth” and similar approaches before turning to the Gilgamesh poems, Homeric epics, and John Prine’s “Spanish Pipedream” as specific examples. The chapter closes with a reflection on biodiversity and cultural diversity as an explanation for the so-called “Greek Miracle”.

From chapter 3

“Long before humans started writing about narratives and identifying their parts, we knew that stories had power and cultivated them for it. Human intervention has shaped narrative in much the same way as we have shaped agricultural crops and domesticated animals. Evolution does not stop because of domestication; instead it moves at a different pace and alters the agents of domestication as well. Humankind and human culture have been inalterably changed by the changes we have wrought on other species.”

Chapter Four. Going Viral: Big Deeds and Bad Fame

Chapter 4 explores the relationship between story and human culture in the world by examining kleos in Homer, Archaic Greek and Greek inscriptions from the perspective of mutualism, parasitism, and viral growth. The discussion emphasizes how the discourse of fame can have a range of outcomes for human communities.

From chapter 4

“There are two reasons why the rhetoric of fame fits well in a discussion of symbiosis. The first is that kleos narratives clearly seem to shift to fit their environment and to have a real impact on the people who tell and hear them. The second is that kleos appears to offer new life through the generation of new stories.”

Chapter Five. Symbiosis and Paradigm: What Stories Do in the World

Chapter 5 continues with biological examples of mutualism and parasitism, emphasizing a symbiotic scale and how relationships can change over time from beneficial to harmful. This chapter then provides interpretations of the Iliad and Odyssey that foreground the poems’ own understanding of how dangerous stories can be in the world. The final part of the chapter will return to how myths can go terribly wrong, discussing the hero Kleomēdēs the Astupalaian and the example of school shootings in the U.S. (especially Columbine).

From chapter 5

“If we accept that the problem of mass violence is not simply one of individual mental health but also part of a deficiency in our social order, in the long term we need to change the stories we tell about ourselves and each other; we need to educate our community about how narratives condition us; and we need to consider whether our social organization allows people to live lives of meaning.”

Conclusion. Inoculation and the Limits of Analogy

The conclusion takes the analogy of story as a living thing one step further, asking readers to think about the relationship between the stories we tell and the way we act in the world and what happens when they become parafunctional. The second part of the conclusion offers a survey of other approaches to narrative and challenges to narrativity, like that from Galen Stawson and E. M. Cioran. Authors discussed include: Jonathan Gottshalk, Mark Turner, Yuval Harari, Benjamin Labatut, Zakkiyah Iman Jackson, Peter Brooks, Angus Fletcher, Robert Shiller, Florian Fuchs, and Liu Cixin. The book closes with brief proposals for educating a world we share with narrative.

From the acknowledgements: Many people make books:

Particular parts of the book were improved in talks given at the Greek Literature and the Environment Workshop, UCSB, the University of Chicago Rhetoric and Poetics, Homer Lecture, and work presented at the Brandeis Psychology department colloquia series… Some of the ideas and passages also appeared in pieces for The Conversation or Neos Kosmos.

I owe a debt to many for help with bibliography and subjects beyond my expertise, including Joseph Cunningham, Sophus Helle, Prasad Jallepalli, Dan Perlman Seth Sanders, Claudio Sansone and Mario Telo. I cannot thank Eric Blum, Becca Frankel, and Talia Franks enough for editing and bibliographical assistance. Among the many friends who have supported my flights of fancy over the years, I would be remiss not to thank Lenny Muellner, Mimi Kramer, Justin Arft, Elton Barker, Celsiana Warwick, Julio Vega-Payne, Anna Hetherington, Paul O’Mahony, Sarah Bond, and Larry Benn, all of whom read drafts of or discussed various parts of this book and provided needed encouragement. Special thanks are due to my editor Heather Gold who provided the focus and the framework to help turn a half-baked idea into a full manuscript. Elizabeth Sylvia also provided invaluable editorial support,, and Susan Laity’s careful eye improved the book’s prose and style immeasurably.

And, as always, my spouse, Shahnaaz, deserves the final word—my belief in the future and any confidence I have starts with her.