This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 22. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

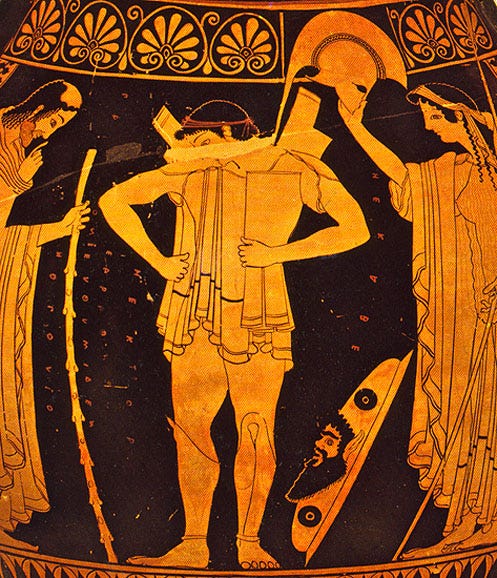

The most memorable details of Iliad 22 are probably Hektor running away from Achilles, then being tricked to facing him by Athena, and, finally, the mistreatment of his corpse before the book’s end. Before the antagonists face each other, however, Hektor has a remarkable speech where he chides himself for not taking advice to retreat within the walls earlier. He confesses that fear of shame—both for cowardice and for wasting so many Trojan lives—keeps him from returning to the city at this point.

In the final moments before he faces Achilles, when the narrative describes him as a coiled snake, Hektor imagines a different outcome. His dream-world can help us understand what happens in the rest of the book.

Iliad 22.111-128

“I wish I could put my embossed shield down

Along with my mighty helmet, then lean my spear against the wall,

And go face-to-face with blameless Achilles.

I’d promise him Helen and the possessions along with her,

Everything that Alexander took in his hollow ships

When he went to Troy, the very beginning of our conflict,

To give her back to the sons of Atreus and in addition

To divide up all the things this city has kept safe.

Then I would have an oath sworn among the Trojan elders

Not to hide anything at all, but to divide up everything,

Every possession the lovely city keeps inside.

But why does my dear heart discuss these things?

I can’t go forward and approach him—he wouldn’t pity me

Nor feel any shame at all, but he will kill me even unarmed

Just the way he would a woman, once I lay my weapons down.

There’s no way at all from oak or stone

To sweet-talk him, the way that a young woman and a young man

or a young man and a young woman sweet talk one another.”εἰ δέ κεν ἀσπίδα μὲν καταθείομαι ὀμφαλόεσσαν

καὶ κόρυθα βριαρήν, δόρυ δὲ πρὸς τεῖχος ἐρείσας

αὐτὸς ἰὼν ᾿Αχιλῆος ἀμύμονος ἀντίος ἔλθω

καί οἱ ὑπόσχωμαι ῾Ελένην καὶ κτήμαθ’ ἅμ’ αὐτῇ,

πάντα μάλ’ ὅσσά τ’ ᾿Αλέξανδρος κοίλῃς ἐνὶ νηυσὶν

ἠγάγετο Τροίηνδ’, ἥ τ’ ἔπλετο νείκεος ἀρχή,

δωσέμεν ᾿Ατρεΐδῃσιν ἄγειν, ἅμα δ’ ἀμφὶς ᾿Αχαιοῖς

ἄλλ’ ἀποδάσσεσθαι ὅσα τε πτόλις ἧδε κέκευθε·

Τρωσὶν δ’ αὖ μετόπισθε γερούσιον ὅρκον ἕλωμαι

μή τι κατακρύψειν, ἀλλ’ ἄνδιχα πάντα δάσασθαι

κτῆσιν ὅσην πτολίεθρον ἐπήρατον ἐντὸς ἐέργει·

ἀλλὰ τί ἤ μοι ταῦτα φίλος διελέξατο θυμός;

μή μιν ἐγὼ μὲν ἵκωμαι ἰών, ὃ δέ μ’ οὐκ ἐλεήσει

οὐδέ τί μ’ αἰδέσεται, κτενέει δέ με γυμνὸν ἐόντα

αὔτως ὥς τε γυναῖκα, ἐπεί κ’ ἀπὸ τεύχεα δύω.

οὐ μέν πως νῦν ἔστιν ἀπὸ δρυὸς οὐδ’ ἀπὸ πέτρης

τῷ ὀαριζέμεναι, ἅ τε παρθένος ἠΐθεός τε

παρθένος ἠΐθεός τ’ ὀαρίζετον ἀλλήλοιιν.

Hektor paints a vivid scene of disarming and meeting Achilles to make a truce. The language throughout is filled with references to pity and shame, those softer cultural correctives against the worst behavior. He also emphasizes redistributing goods, perhaps reaching back to the beginning of the epic when Achilles and Agamemnon fought over war spoils, but ultimately, Hektor knows neither his disarming nor the redistribution of goods is going to make a difference. Achilles is not merely upset, he is enraged. His loss of honor in book 1 led him to question and perhaps abandon the entire system of shame and esteem to which Hektor alludes. The death of Patroklos at Hektor’s hands, moreover, shook Achilles’ cosmic reality.

Schol. Ad Il. 22.126 bT

”There’s no way from oak or stone to sweet-talk him” to describe ridiculous ancient sayings: it is either from the generation of humans who were in the mountains, or it is because early people said they were ash-born or from the stones of Deukalion. Or it is about providing oracles, since Dodona is an oak and Pytho was a stone. Or it means to speak uselessly, coming from the leaves around trees and the waves around stones. Or it is not possible for him to describe the beginning of the human race.

<οὐ μέν πως νῦν ἔστιν> ἀπὸ δρυὸς οὐδ’ ἀπὸ πέτρης / τῷ ὀαριζέμεναι: ληρώδεις ἀρχαιολογίας διηγεῖσθαι, ἢ ἀπὸ τοῦ τὸ παλαιὸν ὀρεινόμων ὄντων τῶν ἀνθρώπων ἐκεῖσε τίκτεσθαι ἢ ἐπεὶ μελιηγενεῖς λέγονται οἱ πρώην ἄνδρες καὶ <λαοὶ> ἀπὸ τῶν λίθων Δευκαλίωνος. ἢ χρησμοὺς διηγεῖσθαι (Δωδώνη γὰρ δρῦς, πέτρα δὲ Πυθών). ἢ περιττολογεῖν, ἀπὸ τῶν περὶ τὰς δρῦς φύλλων καὶ περὶ τὰς πέτρας κυμάτων. ἢ οὐκ ἔστιν αὐτῷ τὴν ἀρχὴν τοῦ γένους διηγεῖσθαι τῶν ἀνθρώπων.

When Hektor declares that “There’s no way at all from oak or stone...” to talk to Achilles, he uses a proverbial comment to tap into a cosmic/metaphysical assertion: Achilles is beyond shame and pity, he is beyond seeing anyone else in the world as more than an obstacle to his ends. But he still ruminates and fantasizes. In my first post on book 22, I suggest that we see Hektor as frozen in that moment of fight or flight for years, wrangling with the trauma of inaction and desperation. Fabian Horn, in an article from 2018, argues similarly that Hektor exhibits a combat stress reaction along with post-traumatic stress disorder—that he runs not from death but from a world lost in fear and out of his control

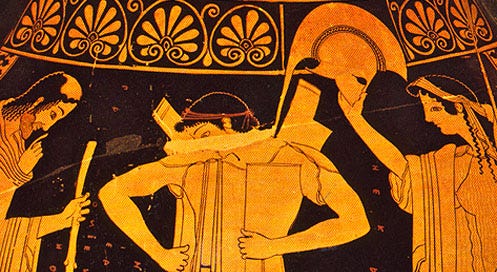

To add to these readings, I think we also need to think about what Hektor longs for, what he desires. Rachel Lesser considers Hektor and Achilles at some length in her recent book, Desire in the Iliad (2022, 208-214). In discussing lines 123-138, Lesser suggests that “When Hektor concludes, “he will kill me naked, just like a woman,” he acknowledges Achilleus’ unstoppable aggression and imagines himself as a vulnerable and passive victim” (209), emphasizing that Hektor imagines a equal relationship, one not of assault but of courtship (following Owen 1946’s observation that Hektor echoes his exchange with Andromache in that book—the language of intimate conversation Hektor uses here (e.g. ὀαρίζετον) appears there as well (cf. Il. 6.516). Such an image of romance, I think, dials back the story of the Iliad to the time before the beginning of the trouble. His repetition of youth and maiden, maiden and youth, shows him stumbling over the image, nearly trying to will it into being despite its impossibility.

Lesser argues that this erotic—in terms of courtly or romantic—language is operative throughout the faceoff between Achilles and Hektor, pervading the former’s eagerness and passion and helping us to understand the heightened language to describe Hektor and “[providing] a window into Achilleus’ psychology thatsupports the interpretation of Achilleus’ libidinal fixation on Hektor as an external displacement of his ambivalent longing for Patroklos. The final death blow to Hektor is a kind of “sexual consummation” as Achilles’ spear enters his enemy’s neck (211).

I really like the formulation of understanding Achilles’ “displacement” of his intensity for Patroklos onto the fire of his rage towards Hektor. There is a slippage that occurs in intense emotions we can observe here as Achilles identification with Patroklos moves from an acceptance of surrogacy in book 16 to a lamentation about what that surrogacy actual means in books 18 and 19 to redirecting it towards Hektor. Hektor becomes the reason Achilles lost part of himself but also a target for the emotional immensity so characteristic of Peleus’ only son. In addition to displacement, however I think there is also a kind of complementarity modeled by Hektor’s speech itself.

When Hektor imagines himself and Achilles as young lovers, he may make himself passive to Achilles’ agent, but he also positions them in a complementary stance to negotiate a different outcome to their conflict. Both in the repetition of identities near the end and in the overall scenario, Hektor imagines an egalitarian relationship where Achilles pursues him through speech, in a less aggressive and less destructive way than the actual outcome. For us as modern readers, however, it can be easy for us to misunderstand some of the assumptions attending marriage for Homeric audiences. One of the most well-known quotes about marriage from antiquity is the blessing Odysseus offers to Nausikaa in Odyssey 6 (6.180-185)

“May the gods grant as much as you desire in your thoughts,

A husband and home, and may they give you fine likemindedness,

For nothing is better and stronger than this

When two people who are likeminded in their thoughts share a home,

A man and a wife—this brings many pains for their enemies

And joys to their friends. And the gods listen to them especially”σοὶ δὲ θεοὶ τόσα δοῖεν ὅσα φρεσὶ σῇσι μενοινᾷς,

ἄνδρα τε καὶ οἶκον, καὶ ὁμοφροσύνην ὀπάσειαν

ἐσθλήν: οὐ μὲν γὰρ τοῦ γε κρεῖσσον καὶ ἄρειον,

ἢ ὅθ᾽ ὁμοφρονέοντε νοήμασιν οἶκον ἔχητον

ἀνὴρ ἠδὲ γυνή: πόλλ᾽ ἄλγεα δυσμενέεσσι,

χάρματα δ᾽ εὐμενέτῃσι, μάλιστα δέ τ᾽ ἔκλυον αὐτοί.

This passage is often viewed as a positive statement on marriage, while it also articulates a notion of justice (hurting friends/helping enemies) that is debated in Plato’s Republic as well. As James Redfield argues in his book The Locrian Maidens, the language of marriage and political stability overlap in emphasis in similarity of thought (more often homonoia). But as the story of the Odyssey shows, what this often means is the occluding of the desires and the interests of the passive/subordinate group by the values and interests of the group in power. Hektor gives up the possessions of Troy as something like a bridegift, yielding to Achilles what he wishes Achilles would desire in place of his blood and life.

There’s another angle to the moment that it took me a modern novel to see more clearly. Guy Gavriel Kay’s The Lions of Al-Rassan uses a medieval fantasy world to retell the story of Muslim Spain during the time of El Cid. Two of the primary characters, the cavalry captain Rodrigo Belmonte and the warrior/poet Ammar ibn Khairan end up on opposite sides of the war as the ‘foreigners’ are driven back across the sea. The two men start out as uneasy allies and are driven apart by diverging loyalties until they lead armies against each other.

One of the most remarkable scenes in a remarkable book comes near the end when Rodrigo and Ammar face each other on the field in single-combat. When the two approach that final moment, Kay leaves a silence to be filled by the audience: “No one escorted either man, so no one knew what it was that Rodrigo Belmonte and Ammar ibn Khairan said to each other when they stopped their horses a little distance apart, alone in the world.” Their former intimacy remains private, informing and anticipating the action to come.

The unfolding duel is watched by a woman named Jehane who loves them both. As she watches, the narrative moves and obscures their identities. One of the men thinks as the scene moves on:

It would have been pleasant, the thought came to him, to be able to lay down their weapons on the darkening grass. To walk away from this place, from what they were being made to do, past the ruins, along the river and into the woods beyond. To find a forest pool, wash their wounds and drink from the cool water and then sit beneath the trees, out of the wind, silent as the summer night came down.

As she observes this scene, Rodrigo’s wife, Miranda remembers, “But she had never, ever heard Rodrigo speak of another man—not even Raimundo, who had died so long ago—the way he’d talked about Ammar ibn Khairan during the long, waiting winter just past. The way the man sat a horse, handled a blade, a bow, devised strategies, jested, spoke of history, geography, the properties of good wine. Even the way he wrote poetry.”

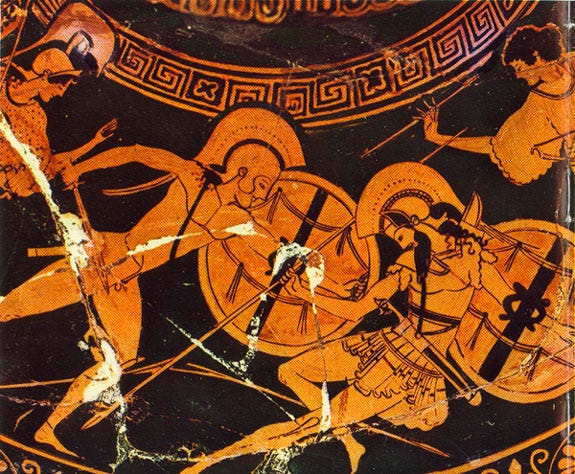

Rodrigo and Ammar are different men in many ways, but they are united in their dedication to their people and their sense of duty. When Hektor briefly imagines chatting with Achilles and sharing a world outside of war with him, I imagine him, the breaker of horses, as occupying such a complementary space, where one fills the space left by another. Indeed, as Owen Lee argues, Hektor and Achilles are both versions of heroes who change the world, who bring a new reality into being. They mirror and refract, but do not perfectly overlap. As the duel continues in The Lions of Al-Rassan, it becomes difficult to trace who strikes and who defends and, in the final moments, it is left briefly unclear which warrior survives.

The interplay of love and death, of longing and fear, in the final moments between Rodrigo and Ammar has led me to see more of what Rachel Lesser sees in Hektor’s final moments. Achilles, Patroklos, and Hektor represent something of a trans-mortal triangle, as each represents life and/or death for the others and a series of replacement and displacement that alters the world they all briefly shared. The greatness of either hero is measured by the other—Hektor’s death matters in part because of Achilles’ life, their stories are entwined in the Iliad to the point that the differences are nearly obscured. As Kay writes of the duel in The Lions of Al-Rassan: “Most of the time, eyes narrowed against the sun, Jehane could tell them apart. Not always, though, as they overlapped and merged and broke apart. They were silhouettes now, no more than that, against the last red disk of light.”

The signal difference in Lions, however, is that dreadful balance between duty and rage. The heroes of Kay’s world are driven by the loyalties to face one another; Achilles and Hektor are driven by their roles into a series of choices that upends duty and common sense and leads them both to their deaths. But in Hektor’s speech we find a different desire that anticipates the very elision Kay describes: when he speaks contra-factually of Achilles’ ability to pity him or feel shame in his treatment, he echoes the very language Priam uses of Achilles in book 24 (503-504):

“But revere the gods, Achilles, and pity him,

thinking of your own father. And I am more pitiable still…”ἀλλ’ αἰδεῖο θεοὺς ᾿Αχιλεῦ, αὐτόν τ’ ἐλέησον

μνησάμενος σοῦ πατρός· ἐγὼ δ’ ἐλεεινότερός περ

Priam, even if briefly, becomes for Achilles what rage makes impossible for Hektor: another human being whose love and brief light in the world reminds him of his own. The tragedy of Rodrigo and Ammar is that they find this in each other but then must leave it behind; Hektor and Achilles never have the time to find this in each other and Priam and Achilles are allowed only a brief glimpse before they return to their final days.

A short bibliography

Bassett, S. E.. “Achilles' treatment of Hector's body.” TAPA, 1933, pp. 41-65.

Kay, Guy Gavriel. The Lions of Al-Rassan. Viking Canada. 1995.

Jasper Griffin, ‘Achilles kills Hector’, Lampas, XXIII. (1990) 353-369.

Hadjicosti, Ioanna L.. “Hesiod fr. 212B (MW): death at the Skaean gates.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 58, no. 4, 2005, pp. 547-554.

Horn, Fabian. “The psychology of aggression: Achilles’ wrath and Hector’s flight in Iliad 22.131-7.” Hermes, vol. 146, no. 3, 2018, pp. 277-289. Doi: 10.25162/hermes-2018-0023

Lee, M. Owen. “Achilles and Hector as Hegelian heroes.” Échos du monde classique = Classical views, vol. XXX, 1981, pp. 97-103.

Lesser, Rachel. 2022. Desire in the Iliad. Oxford.

Owen, E. T. 1946. The Story of the Iliad. Toronto.

Rabel, Robert J.. “The shield of Achilles and the death of Hector.” Eranos, vol. LXXXVII, 1989, pp. 81-90.

Redfield, James R. The Locrian Maidens: Love and Death in Italy. Princeton, 2004.

Vermeule, Emily D. Townsend. “The vengeance of Achilles. The dragging of Hektor at Troy.” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, vol. LXIII, 1965, pp. 34-52.