This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 16. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Patroklos’ death is one of the most important moments in the Iliad: it advances the plot by redirecting Achilles’ rage toward Hektor and it also engages in some critical themes. The details of how he dies have caused consternation over the years: Apollo strips him of his armor, Eurphorbus wounds him, and then Hektor moves in for the kill. All of this happens after Patroklos has pushed too far, ignoring Achilles’ advice from the beginning of the book and dismissing repeated warnings from Apollo. In doing so, Patroklos engages in what later authors might call hubris in two ways: he oversteps his bounds, arrogating to himself honor and glory destined for Achilles, and he does so despite somewhat direct intervention from the gods.

One of the more important questions in thinking through the end of book 16 is how this depiction of Patroklos’ death informs our reading of Hektor and Achilles. In addition, Patroklos’ demise furnishes further material for thinking through determination and agency in epic: Zeus has previously prophesied Patroklos’ death, thereby making it fated; and, yet, the epic also takes pains to show that Patroklos is in part liable for his own suffering. This is all part of the famous ‘double determination’ that characterizes the pairing of human decisions and behavior within the larger arc of the narrative tradition and divine fate.

Three more topics jump out at me when I look at the final exchange of Patroklos’ life: (1) the Homeric narrator’s direct address to the hero; (2) the ensuing controversies about his actual death; and (3) his brief prophetic power and Hektor’s response.

Homer, Iliad 16. 843-863

“O Patroklos you horseman, then you addressed him, succumbing to weakness:

Now already you are boasting a lot—for Zeus, the son of Kronos

Gave victory to you along with Apollo, and they overcame me

With ease. They are the ones who stripped the armor from my shoulders.

If twenty who are the likes of you had opposed me

They all would have died here, overcome by my spear.

But ruinous fate killed me a long with Leto’s son

And, from men, Euphorbus. You are the third to kill me.

I will tell you something else and keep it in your thoughts.

You’re not going to be here very long yourself, but death

And its overwhelming fate already are standing near you:

To die at the hands of Achilles, Aeacus’ blameless grandson.’

So he spoke and death’s end covered him as he spoke.His soul went flying from his limbs and went to Hades

Lamenting their fate, because they left behind manliness and youth.

As he died, glorious Hektor addressed him:

“Patroklos, why are you prophesying my death to me?

Who knows if Achilles, the child of nice-haired Thetis

May die, struck first by my spear?”

So Hektor spoke and he drew his bronze spear from the wound

Pressing down with his foot as he pushed him away.”Τὸν δ' ὀλιγοδρανέων προσέφης Πατρόκλεες ἱππεῦ·

ἤδη νῦν ῞Εκτορ μεγάλ' εὔχεο· σοὶ γὰρ ἔδωκε

νίκην Ζεὺς Κρονίδης καὶ ᾿Απόλλων, οἵ με δάμασσαν

ῥηιδίως· αὐτοὶ γὰρ ἀπ' ὤμων τεύχε' ἕλοντο.

τοιοῦτοι δ' εἴ πέρ μοι ἐείκοσιν ἀντεβόλησαν,

πάντές κ' αὐτόθ' ὄλοντο ἐμῷ ὑπὸ δουρὶ δαμέντες.

ἀλλά με μοῖρ' ὀλοὴ καὶ Λητοῦς ἔκτανεν υἱός,

ἀνδρῶν δ' Εὔφορβος· σὺ δέ με τρίτος ἐξεναρίζεις.

ἄλλο δέ τοι ἐρέω, σὺ δ' ἐνὶ φρεσὶ βάλλεο σῇσιν·

οὔ θην οὐδ' αὐτὸς δηρὸν βέῃ, ἀλλά τοι ἤδη

ἄγχι παρέστηκεν θάνατος καὶ μοῖρα κραταιὴ

χερσὶ δαμέντ' ᾿Αχιλῆος ἀμύμονος Αἰακίδαο.

῝Ως ἄρα μιν εἰπόντα τέλος θανάτοιο κάλυψε·

ψυχὴ δ' ἐκ ῥεθέων πταμένη ῎Αϊδος δὲ βεβήκει

ὃν πότμον γοόωσα λιποῦσ' ἀνδροτῆτα καὶ ἥβην.

τὸν καὶ τεθνηῶτα προσηύδα φαίδιμος ῞Εκτωρ·

Πατρόκλεις τί νύ μοι μαντεύεαι αἰπὺν ὄλεθρον;

τίς δ' οἶδ' εἴ κ' ᾿Αχιλεὺς Θέτιδος πάϊς ἠϋκόμοιο

φθήῃ ἐμῷ ὑπὸ δουρὶ τυπεὶς ἀπὸ θυμὸν ὀλέσσαι;

῝Ως ἄρα φωνήσας δόρυ χάλκεον ἐξ ὠτειλῆς

εἴρυσε λὰξ προσβάς, τὸν δ' ὕπτιον ὦσ' ἀπὸ δουρός.

Apostrophe in Homer

Whenever I read Homer with people, they will invariably ask why the Homeric narrator uses direct address to a few select characters. The appeal to Patroklos as if in conversation is not a result of a translator’s choice: in the Greek, epic uses the vocative form for Patroklos’ name (i.e., the case ending for a direct address) and 2nd person verbs for the action (the singular “you” forms). Among literary devices, direct-address to a character/person not present is called apostrophe. (It shares the name with the punctuation mark because both the sign and the action are “turning away”, which is the meaning of the Greek word.) As early as Ps. Plutarch’s On Homer, we have the identification of the trope as apostrophe and the idea articulated that it “moves with pathos and makes an impact on the audience.” (ὅπερ ἰδίως ἀποστροφὴ καλεῖται. τῷ δὲ παθητικῷ κινεῖ καὶ ἄγει τὸν ἀκροώμενον, 620-621 )

Several characters in Homer receive this treatment, but only two receive it repeatedly: Patroklos in the Iliad and Eumaios in the Odyssey. The general argument I have always shared for this is that the act creates a sense of identification or sympathy with the the character addressed in Homer, setting them and their experiences aside from the rest of the narrative as something special. From a narratological perspective, Irene J. F. De Jong has classed apostrophe as a kind of metalepsis, that is a device that breaks down the narrative, that draws the audience and narrator together to see the actions in a different way. The effect is both to single the apostrophized character out for special attention and to bring the audiences closer to the experience, to immerse them in it, as Rutger Allan suggests.

The repeated effect in book 16 may draw the audience closer to Patroklos and his decision making, while also increasing the emotional effect of his death and preparing us for Achilles’ extreme response. In addition, I think it contrasts with the treatment of Hektor who seems to inspire so much sympathy among modern audiences. What is the impact of the expressed narrative sympathy for Patroklos on our response to Hektor’s characterization?

He is not even third! Hektor’s Contribution to Patroklos’ Death

I think that one of the under-emphasized themes of books 16 and on is the diminishment of Hektor. While he is posed as late as book 9 as a man-slaying menace, threatening the whole of the Achaean fleet, he is wounded in book 14, resuscitated in book 15, and only allowed to make his critical contribution to the plot after his ally Sarpedon has died, and after Patroklos has pushed the Trojans almost back into the city itself.

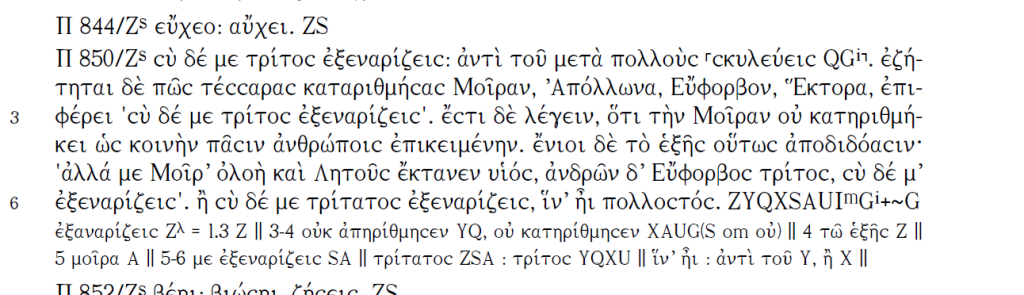

Patroklos notes that Hektor was only third in line to kill him. The D scholia preserve some additional commentary on Hektor’s achievement:

“We need to look at how the count isn’t four including Fate, Apollo, Euphorbos, and Hektor, when Patroklos says “you are killing me third!”. People are saying that he is not counting Fate because she is common for all mortals. Some claim that Patroklos just indicated this when he listed it as he does....these really means he’s last [πολλοστός]”

Hektor’s killing of Patroklos triggers the plot sequence that ends Hektor’s life but it also reshapes our view of his character Steven Lowenstam argues that Patroclus’ death can be shown to reveal ambivalence about excellence in warfare. I think the scene definitely undermines conventional notions of heroism and that it does so by showing Patroklos’ excess and emphasizing Hektor’s limitations.

As William Allan shows, Patroklos’ death anticipates Hektor’s fall in important ways, but it also apparently informs our understanding of the relationship between the Iliad and the lost Aithiopis. Achilles’ eventual death thanks to Paris and Apollo is predicted later in the Iliad. Some authors have argued that it is prefigured in Euphorbus as a doublet for Paris. According to our ancient sources, Achilles’ death actually occurred in the lost Aithiopis. Allan’s discussion about the correlations between these death scenes is nuanced: He suggests that we don’t need to imagine the Iliad or the Aithiopis copying each other: the scenes could be based on conventional patterns, or (and this is my take) they could both be echoing earlier versions of their own narrative traditions (see Jonathan Burgess’ article on this too.)

One of the important motifs Allan focuses on is Euphorbus’ role in the death: while some have seen him as a doublet of other figures, Allan argues that the Homeric narrative gives him an actual backstory: Menelaos killed his brother Hyperenor in book 14 and Hektor is often paired with Polydamas, whose relationship with Hektor I have suggested is a good index for Homeric politics. Hektor’s killing of Patroklos is in a way diminished by his ranking as third in the killers (after Apollo and Euphorbus). The cumulative effect of book 16, one might say, is to emphasize human folly and overreaching. Both Patroklos and Hektor go farther than they are supposed to.

The Prophecy

A traditional motif from early Greek culture is the idea that souls about to die gain some power of prophecy because o their proximity to the divide between mortal and immortal realms

Schol. T in Hom. Il. 16.851

“This is the belief expressed by the poet: souls that are about to make a transition have something of prophetic power. For once they have come closer to divine nature, they get some foreknowledge of what is to come.”

δόγμα ἐστὶ τοῦτο τῷ ποιητῇ ὥστε ἀπαλλασσομένας τὰς ψυχὰς ἔχειν τι μαντικώτερον· πλησίον γὰρ ἤδη τῆς θείας φύσεως γινομένη ἡ ψυχὴ προγινώσκει τι τῶν μελλόντων.

When Hektor dies, he too will provide a prophecy to his killer and will be rejected in a similar way. Hektor’s response here repeats the Trojan refrain that who knows whether they will live or die. Hektor very well suspects what his fate is, as he makes clear in book 6. His articulation of the idea that he may have a puncher’s chance of beating Achilles is different at this moment than when he dismisses his advisors or rallies the Trojans earlier. Here, Hektor is talking to a man as he dies and we have no evidence that anyone else is listening. Hektor’s denial here can be seen either as a taunt for the departing Telemachus or a desperate continuation of his previous attempts to persuade others that their cause is not doomed.

While I think the context is ambiguous–Hektor can be seen as cruelly boastful or in desperate denial–I do think that the characterization is disambiguated by subsequent actions: Hektor foolishly takes up Patroklos’ armor in book 17; he fails to rescue Sarpedon’s body for Glaukos; he refuses to tale his army back to the city as Polydamas advises in book 18; and he is hemmed in by Achilles until he is forced to face him in book 22. At that moment, Hektor expresses his regret. In a way, his narrative arc is a shadow cast by Patroklos’ death: they both fight beyond their fate and die by divine fiat outside the walls of Troy.

Patroklos’ dying taunt of Hektor and Hektor’s subsequent dismissal of his prophecy unite them in a kind of pathos that relativizes and undermines any claims of glory. Patroklos’ ‘great deeds’ transgress and surpass his friends advice and he dies with only the promise of glory to come. Hektor is denied the accomplishment himself. And all that is left in this wake is a heroic rage that does little to elevate the human condition.

A short Bibliography on the end of Iliad 16

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Allan, Rutger. “Metaleptic apostrophe in Homer: emotion and immersion.” Emotions and narrative in ancient literature and beyond: studies in honour of Irene de Jong. Eds. De Bakker, Mathieu, Van den Berg, Baukje and Klooster, Jacqueline. Mnemosyne. Supplements; 451. Leiden ; Boston (Mass.): Brill, 2022. 78-93. Doi: 10.1163/9789004506053_006

Allan, William. “Arms and the man: Euphorbus, Hector, and the death of Patroclus.” Classical Quarterly, N. S., vol. 55, no. 1, 2005, pp. 1-16. Doi: 10.1093/cq/bmi001

Block, E.. “The narrator speaks. Apostrophe in Homer and Vergil.” TAPA, vol. CXII, 1982, pp. 7-22.

Burgess, Jonathan Seth. “Beyond neo-analysis: problems with the vengeance theory.” American Journal of Philology, vol. 118, no. 1, 1997, pp. 1-19. Doi: 10.1353/ajp.1997.0011

Christopoulos, Menelaos. “Patroclus and Elpenor: dead and unburied.” Ο επάνω και ο κάτω κόσμος στο ομηρικό και αρχαϊκό έπος: από τα πρακτικά του ΙΓ’ Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου για την « Οδύσσεια » : Ιθάκη, 25-29 Αυγούστου 2017. Eds. Christopoulos, Menelaos and Païzi-Apostolopoulou, Machi. Ithaki: Kentro Odysseiakon Spoudon, 2020. 163-174.

De Jong, Irene J. F.. “Metalepsis in ancient Greek literature.” Narratology and interpretation: the content of narrative form in ancient literature. Eds. Grethlein, Jonas and Rengakos, Antonios. Trends in Classics. Supplementary Volumes; 4. Berlin ; New York: De Gruyter, 2009. 87-115.

Karakantza, Efimia D.. “Who is liable for blame ? : Patroclus’ death in book 16 of the « Iliad ».” Έγκλημα και τιμωρία στην ομηρική και αρχαϊκή ποίηση : από τα πρακτικά του ΙΒ' διεθνούς συνεδρίου για την Οδύσσεια, Ιθάκη, 3-7 Σεπτεμβρίου 2013. Eds. Christopoulos, Menelaos and Païzi-Apostolopoulou, Machi. Ithaki: Kentro Odysseiakon Spoudon, 2014. 117-136.

Lowenstam, Steven. “Patroclus' death in the Iliad and the inheritance of an Indo-European myth.” Archaeological News, vol. VI, 1977, pp. 72-76.

Parry, A.. “Language and characterization in Homer.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. LXXVI, 1972, pp. 1-22.