Reminder: all proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

One of the most iconic scenes of the Iliad is the exchange between Glaucus and Diomedes in book 6. This scene comes in the middle of book 6, in part as a delaying technique while Hektor travels into the city. But it also continues part of the plot in book 6, where Diomedes wounded Athena and was warned not to attack any of the other gods.

Diomedes: Il. 6.123-129

“Bestie, who are you of mortal humans?

For I have never seen you before in this ennobling battle.

But now you stride out far ahead of everyone

In your daring—where you await my ash-wood spear.

Those who oppose my might are children of miserable parents!

But, if you are one of the immortals come down from the sky,

I don’t wish to fight with the sky-dwelling gods!”τίς δὲ σύ ἐσσι φέριστε καταθνητῶν ἀνθρώπων;

οὐ μὲν γάρ ποτ’ ὄπωπα μάχῃ ἔνι κυδιανείρῃ

τὸ πρίν· ἀτὰρ μὲν νῦν γε πολὺ προβέβηκας ἁπάντων

σῷ θάρσει, ὅ τ’ ἐμὸν δολιχόσκιον ἔγχος ἔμεινας·

δυστήνων δέ τε παῖδες ἐμῷ μένει ἀντιόωσιν.

εἰ δέ τις ἀθανάτων γε κατ’ οὐρανοῦ εἰλήλουθας,

οὐκ ἂν ἔγωγε θεοῖσιν ἐπουρανίοισι μαχοίμην.

Glaukos, 6.145-151

“Oh, you great-hearted son of Tydeus, why are you asking about pedigree?

The generations of men are just like leaves on a tree:

The wind blows some to the ground and then the forest

Grows lush with others when spring comes again.

In this way, the race of men grows and then dies in turn.

But if you are willing, learn about these things so you may know

My lineage well—many are the men who know me.”Τυδεΐδη μεγάθυμε τί ἢ γενεὴν ἐρεείνεις;

οἵη περ φύλλων γενεὴ τοίη δὲ καὶ ἀνδρῶν.

φύλλα τὰ μέν τ’ ἄνεμος χαμάδις χέει, ἄλλα δέ θ’ ὕλη

τηλεθόωσα φύει, ἔαρος δ’ ἐπιγίγνεται ὥρη·

ὣς ἀνδρῶν γενεὴ ἣ μὲν φύει ἣ δ’ ἀπολήγει.

εἰ δ’ ἐθέλεις καὶ ταῦτα δαήμεναι ὄφρ’ ἐὺ εἰδῇς

ἡμετέρην γενεήν, πολλοὶ δέ μιν ἄνδρες ἴσασιν

This scene certainly leaves an impression on people. One of my best friends spent years scheming to re-stage this scene on a paintball field. After may abortive events, some of us laid down covering fire so he and another could meet an exchange their equipment midfield. It was hilarious. And unsafe. But hilarious.

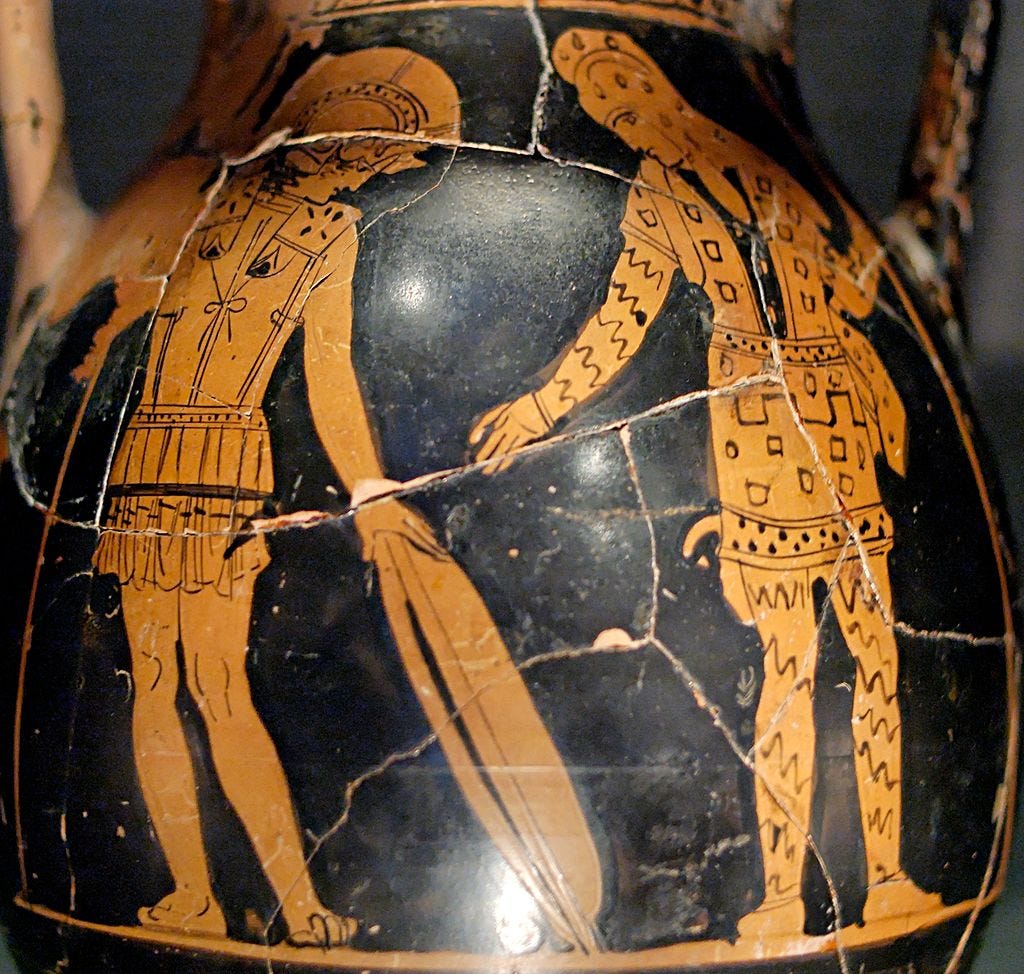

The exchange between these two heroes is marked by three things (among others!): (1) the establishment of xenia–the reciprocal exchange of hospitality–as an inheritable principle; (2) Glaukos’ telling of the story of Bellerophon (which establishes the aforementioned xenia status); and (3) the exchange of armor to signal their continuing friendship.

The exchange is marked with a strong note of judgment by the Homeric narrator.

Homer, Iliad 6.230-236

“Let’s exchange armor with one another so that even these people

May know that we claim to be guest-friends from our fathers’ lines.”So they spoke and leapt down from their horses,

Took one another’s hands and made their pledge.

Then Kronos’s son Zeus stole away Glaukos’ wits,

For he traded to Diomedes golden arms in exchange for bronze,

weapons worth one hundred oxen traded for those worth nine.”τεύχεα δ’ ἀλλήλοις ἐπαμείψομεν, ὄφρα καὶ οἷδε

γνῶσιν ὅτι ξεῖνοι πατρώϊοι εὐχόμεθ’ εἶναι.

῝Ως ἄρα φωνήσαντε καθ’ ἵππων ἀΐξαντε

χεῖράς τ’ ἀλλήλων λαβέτην καὶ πιστώσαντο·

ἔνθ’ αὖτε Γλαύκῳ Κρονίδης φρένας ἐξέλετο Ζεύς,

ὃς πρὸς Τυδεΐδην Διομήδεα τεύχε’ ἄμειβε

χρύσεα χαλκείων, ἑκατόμβοι’ ἐννεαβοίων.

Ancient commentators were intrigued by this judgment.

Schol. ad. Il. 6.234b ex.

“Kronos’ son Zeus took Glaukos’ wits away”. Because he was adorning him among his allies with more conspicuous weapons. Or, because they were made by Hephaistos. Or, as Pios claims, so that [the poet?] might amplify the Greek since they do not make an equal exchange—a thing which would be sweet to the audience.

Or, perhaps he credits him more, that he was adorned with conspicuous arms among his own and his allies. For, wherever these arms are, it is a likely place for an enemy attack.”

ex. ἔνθ’ αὖτε Γλαύκῳ <Κρονίδης> φρένας ἐξέλετο: ὅτι κατὰ τῶν συμμάχων ἐκόσμει λαμπροτέροις αὐτὸν ὅπλοις. ἢ ὡς ῾Ηφαιστότευκτα. ἢ, ὡς Πῖος (fr. 2 H.), ἵνα κἀν τούτῳ αὐξήσῃ τὸν ῞Ελληνα μὴ ἐξ ἴσου ἀπηλ<λ>αγμένον, ὅπερ ἡδὺ τοῖς ἀκούουσιν. T

ἢ μᾶλλον αἰτιᾶται αὐτόν, ὅτι λαμπροῖς ὅπλοις ἐκοσμεῖτο κατὰ ἑαυτοῦ καὶ τῶν συμμάχων· ὅπου γὰρ ταῦτα, εὔκαιρος ἡ τῶν πολεμίων ὁρμή. b(BE3E4)

I always thought that Glaukos got a raw deal from interpreters here. Prior to the stories Diomedes and Glaukos tell each other, Diomedes was just murdering everyone in his path. Glaukos—who already knew who Diomedes was before he addressed him—tells a great tale, gives Diomedes his golden weapons, and actually lives to the end of the poem. I think this is far from a witless move. And, if the armor is especially conspicuous, maybe the plan-within-a-plan is to put a golden target on Diomedes’ back.

But let’s back up a bit to make a few points:

Diomedes does not know who Glaukos is; Glaukos definitely knows who Diomedes is.

Everyone among the Trojans knows that Diomedes has been tearing it up in the field and that few can meet him.

Diomedes prefaces his question of Glaukos’ identity by telling him a story of how Lykourgos messed with the gods and regretted it, providing a bit of a proverbial lesson by concluding that no one lasts long “once they have become hateful to the gods” (ἦν, ἐπεὶ ἀθανάτοισιν ἀπήχθετο πᾶσι θεοῖσιν, 6.140).

Then, Glaukos tells an elaborate tale about his ancestry that links up with Diomedes’ grandfather, concluding that Bellerophon “became hateful to the gods” (using the same language as Diomedes at line 200)

This narrative confirms Diomedes’ sentiment that anyone can fall out of favor, while also bulking up Glaukos’ heroic profile and providing him an out clause (xenia)

Just as everyone knows who Diomedes is, they also seem to know his famous father as one of the failed Seven against Thebes

So, when Diomedes says that he doesn’t remember his father (222), we might be able to argue that Glaukos is counting on this: Diomedes knows some object left behind in his family’s home, but cannot confirm or deny the story Bellerophon says.

In my work on the Odyssey (The Many Minded Man: the Odyssey, Psychology and The Therapy of Epic) I argue, following authors like Lisa Zunshine and Palmer, that good storytellers exhibit mind-reading, by which they mean the ability to “ascribe states of minds to others and [themselves]”. While this is seen by modern authors as a sign of sophistication in novels, I think it is something we can see in the case of effective liars and persuaders like Odysseus. I summarize (2020, 150):

For Lisa Zunshine, the ability to ascribe to someone else “a certain mental state on the basis of her observable action” (2006:6)—what she calls “mind-reading”—is both an essential skill for “construct[ing] and navigat[ing] our social environment” and a foundational quality for the creation of fiction and literature.2 Such an ability is in part what makes Odysseus a great story-teller and a narrative agent; but it also allows him to subjugate and use others.

In short, I think there is a reading of Glaukos’ use of Bellerophon’s narrative that shows it works similarly to Odysseus’ lies: he weaponizes a story to achieve a complex outcome. In Glaukos’ case, he establishes a hereditary relationship with Diomedes that allows him to avoid fighting the most dangerous person on the battlefield.

Some things to read on book 6

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Alden, M. J. “Genealogy as Paradigm: The Example of Bellerophon.” Hermes, vol. 124, no. 3, 1996, pp. 257–63. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4477146

Donlan, Walter. “The Unequal Exchange between Glaucus and Diomedes in Light of the Homeric Gift-Economy.” Phoenix, vol. 43, no. 1, 1989, pp. 1–15. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1088537. Accessed 2 Oct. 2023.

Fineberg, Stephen. “Blind Rage and Eccentric Vision in Iliad 6.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), vol. 129, 1999, pp. 13–41. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/284423.

Gaisser, Julia Haig. “Adaptation of Traditional Material in the Glaucus-Diomedes Episode.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, vol. 100, 1969, pp. 165–76. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2935907.

Harries, Byron. “‘Strange Meeting’: Diomedes and Glaucus in ‘Iliad’ 6.” Greece & Rome, vol. 40, no. 2, 1993, pp. 133–46. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/643154.

Lowry, Eddie R.. “Glaucus, the leaves, and the heroic boast of Iliad 6.146-211.” The ages of Homer: a tribute to Emily Townsend Vermeule. Eds. Carter, Jane P. and Morris, Sarah P.. Austin (Tex.): University of Texas Pr., 1995. 193-203.

Palmer, Alan. 2010. Social Minds in the Novel. Columbus.

Scodel, Ruth. “The Wits of Glaucus.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), vol. 122, 1992, pp. 73–84. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/284365.

Tracy, Catherine. “The Host’s Dilemma: Game Theory and Homeric Hospitality.” Illinois Classical Studies, no. 39 (2014): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5406/illiclasstud.39.0001.

Traill, David A. “Gold Armor for Bronze and Homer’s Use of Compensatory TIMH.” Classical Philology, vol. 84, no. 4, 1989, pp. 301–05. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4620748

Walcot, Peter. “Χρύσεα χαλκείων. A further comment.” Classical Review, vol. XIX, 1969, pp. 12-13. Doi: 10.1017/S0009840X00328311

Zunshine, Lisa. 2006. Why We Read Fiction: Theory of Mind and the Novel.

Columbus.

Makes perfect sense. By the way, I taught a course on Homer to incarcerated students last semester through Wesleyan University and assigned some of your work. Glad to see you here on Substack.