This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 19. Here is a link to the overview of Iliad 18 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

The 19th book of the Iliad joins books 17 and 18 in postponing Achilles’ return to war and the transfer of his rage from the Achaeans to Hektor. While it is certainly true that the further delaying of the main event creates suspense in audiences, it would be a mistake to insist that this is all the book does. One of the important tasks for book 19 is to resolve the political conflict among the Greeks just enough to get them to return to battle. Thematically, however, it is too early in the plot to dispense with political themes altogether. So the book we get is an odd combination of ‘reconciling’ Agamemnon and Achilles and preparing the rest of the Greeks for battle.

In between these plot points there’s a little more, of course. Achilles tries not to fully engage with the public resolution, but must; he tries to avoid joining the community, and despite Odysseus’ attempts to convince them, he remains apart from them even while confirming he is a part of them. Once the public reconciliation is over, we get to hear Briseis speak for the first time in the epic, Achilles’ horses neigh, I mean, weigh in on affairs, and Athena ‘juices’ Achilles up with nektar and ambrosia because he refuses to eat until he has avenged his friend’s death. Oh, in the middle of all of this Agamemnon gives his most rhetorically effective speech in the epic. And soon after Achilles laments Patroklos again, did I mention that his horse tells him that he’s doing to die?

Each of these sections adds something to the themes I have outlined in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions. Among these, however, I think book 19 speaks most directly to narrative traditions, politics and heroism.

The Stories We Tell; the Stories We Are

One of the things that is most remarkable about the political exchange at the beginning of Iliad 19 is the way the first two significant speeches engage with concerns about stories and storytelling. Achilles arrives and seems to indicate that he understands that he and Agamemnon are in a narrative other people will talk about in the future and then Agamemnon tells a story to explain/excuse his own behavior that may also contain a coded message about how to understand his relationship with Achilles.

Achilles starts the conversation:

Homer, Iliad 19.56-64

‘Son of Atreus, was this really better at all

for you and me, that we, even though we were upset,

raged with heart-rending strife because of a girl?

I wish that Artemis had killed her among the ships with an arrow

on that day when I took her after destroying Lurnêssos;

that way, so many Achaians wouldn’t have bitten the dust

at the hands of wretched men while I was raging.

That was more profitable for Hektor and the Trojans, but I think

that the Achaians will remember your and my strife for a long time.’᾿Ατρεΐδη ἦ ἄρ τι τόδ’ ἀμφοτέροισιν ἄρειον

ἔπλετο σοὶ καὶ ἐμοί, ὅ τε νῶΐ περ ἀχνυμένω κῆρ

θυμοβόρῳ ἔριδι μενεήναμεν εἵνεκα κούρης;

τὴν ὄφελ’ ἐν νήεσσι κατακτάμεν ῎Αρτεμις ἰῷ

ἤματι τῷ ὅτ’ ἐγὼν ἑλόμην Λυρνησσὸν ὀλέσσας·

τώ κ’ οὐ τόσσοι ᾿Αχαιοὶ ὀδὰξ ἕλον ἄσπετον οὖδας

δυσμενέων ὑπὸ χερσὶν ἐμεῦ ἀπομηνίσαντος.

῞Εκτορι μὲν καὶ Τρωσὶ τὸ κέρδιον· αὐτὰρ ᾿Αχαιοὺς

δηρὸν ἐμῆς καὶ σῆς ἔριδος μνήσεσθαι ὀΐω.

One of the things I emphasize about this passage in an article about strife and epic is that the repeated use of eris indicates something of a ‘titling’ function. There are other epic motifs and traditions that are marked by this word and when Achilles uses it with a word for recalling/remembering, he is giving the impression that his actions will be part of someone else’s story. This is the kind of compressed language that is used to mark stories that are part of the klea andrôn discussed in posts on book 9. I think that Achilles is showing that he knows other people are already using his actions as a cautionary tale even as the Iliad is anticipating or announcing its own status as a paradigmatic narrative. In conjunction with this, Achilles offers an interpretation for internal and external audiences: this whole conflict was foolish because it was over a girl. And, it was better for their opponents. The reference to a “girl” is ambiguous to the point that any reasonable audience member could make the leap from the plot of the Iliad to the cause of the whole war.

So, Achilles’ speech metapoetically positions the Iliad as the kind of tale people should be judging for its effects on the world and which people should recall to make sense of their own lives or to use as a (counter)-example for their choices. This swift sequence prepares the audience for thinking about narrative interactions and how individuals and events in one story (or life) can map onto another to bring the meaning of both into relief.

And with this priming action made, Agamemnon arrives for his most dynamic speech of the epic. Once Achilles makes his statement, he basically insists on letting bygones be bygones because he wants to take the fast track to large-scale slaughter. The problem with this is that Agamemnon needs to go through the performance of reconciliation to reestablish his authority over Achilles before they return to war. Agamemnon ruminates a bit on public speaking—after making a show of not being able to stand because of his injury suffered in battle, and then launches into a dizzying and remarkable speech

‘Atê is the oldest daughter of Zeus, the one who blinds everyone,

the ruinous one—her feet are light, for she never touches

the ground, instead she walks over the heads of men

and harms people as she goes, therein she binds one or another.

For, even Zeus indeed was once blinded, even though they say

that he is the best of men and gods; but really, Hera

since she’s female, deceived him with tricky-thoughts

on that day when Alkmene was about to give birth

to powerful Herakles in well-garlanded Thebes.

Truly, Zeus was boasting among all the gods then:

‘Hear me all you gods and all you goddesses

so that I may speak what the heart in my chest bids.

Today labor-bringing Eileithuia will show to the light of day

a man who will rule over all those who live around him,

an offspring of men who is also from my bloodline.’

Queen Hera, who was deceit-minded, then addressed him:

‘You lie and will not ever bring a completion to your plan.

Come now, swear a strong oath to me, Olympian,

that the man will really rule over all his neighbors

who on this day falls between the feet of a woman

from men who are offspring from your blood.’

So she spoke, but Zeus did not notice that she was being deceitful,

and he swore a great oath and thereupon was much blinded.

Then Hera leapt up and left the peak of Olympos

and quickly came to Achaian Argos where she found then

the strong wife of Sthenelos the son of Perseus

who was bearing a dear child and he was at his seventh month;

she led him to the life even though he was premature

and stopped the labor of Alkmene—she held back Eileithuia.

Then, she herself went as a messenger and addressed Zeus, Kronos’ son:

‘Zeus-father who delights in lightning, I will put a word in your thoughts;

for already a fine man who will rule over the Argives has been born,

Eurystheos, the child of Sthenelos, Perseus’ son,

your offspring—it is not unseemly for him to rule the Argives.’

So she spoke and a sharp grief cut through his deep mind.

Immediately he grabbed Atê by her well-tressed head

as he raged in his thoughts and swore a great oath

that she who blinds all would never come again

to Olympos and the starry sky.

As he said this he threw her from starry heaven,

once he had his hands around her, and she soon came to the works of men.

He lamented her always whenever he saw his own dear son

taking up the unseemly work of labors under Eurystheos.

So I too, when again and again great Hektor of the shining helm

was destroying the Argives near the prows of the ships,

I was not able to forget Atê by whom I was first blinded.

But since I was blinded and Zeus deprived me of my wits,

I wish to reconcile and to give a shining ransom.’

Zeus starts with a story about “Atê” that seeks to exculpate him for his actions. At some level, we can accept his claim as being as verifiable as claiming “the devil made me do it” but he expands the comparison to say that even Zeus was blinded by Atê. So far, he makes the implicit claim that he is like Zeus and should be pardoned a disastrous mistake because even the king of the universe has screwed up. But then he shifts the tale, and this is where I think most people miss the point.

In the story Agamemnon tells, the specific instance of Zeus’ blindness was in boasting about the birth of a son who was going to be greater than everyone else. Hera tricked him into swearing an oath about it, and then through this oath and her machinations it turned out that Eurystheos—a distant descendent—was born in the appointed place of Herakles—the demigod destined to be the best hero ever. The story explains how even the king of the gods can lose control over the situation (as Agamemnon did) but it also offers what I see as a coded apology or explanation to Achilles about their situation.

The conflict in book 1 set a traditional king with a lot of power against a powerful demigod. Part of their conflict arose from a struggle over their respective honors given the difference in their implicit authority (Agamemnon) based on nobility of birth and place and their acquired authority, based on ability and performance. Achilles loses faith in the entire system of honor and in the Achaean community itself when his disproportionally extraordinary abilities are not matched with proportionally exceptional honors.

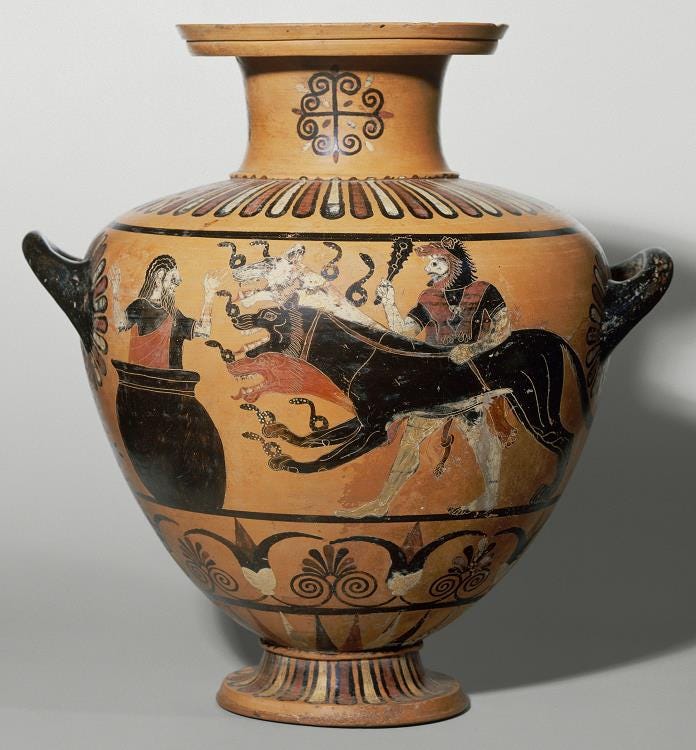

Of course, that last sentence is an overstatement. Achilles loses his wits in book 1 when he discovers that his ability and performance cannot safeguard him against abuse by someone of lesser ability in a greater position of power. When Agamemnon tells the story of Zeus’ mistake, he focuses on a similar injustice: even though Herakles is better by birth and ability, the exigencies of chance and fate set him as subordinate to a lesser man of greater political position. But beyond that is the issue of Herakles himself: he serves Eurystheos because of his own mistakes and excesses (and the anger of Hera). But, we can’t overlook the fact that Agamemnon/Eurystheus suffers in this equation too.

So one interpretation of Agamemnon’s story is that he means for Achilles to understand that the two of them are in analogous positions, that while Achilles is the greater warrior and more exceptional man, Agamemnon is the “kinglier”. Their positions are neither of their faults, but both of their responsibilities to understand. Whether the internal audience of the poem comprehends these comparisons and whether or not Achilles himself is meant to understand the implication that he too, like Herakles, suffers because of his own actions, cannot be known. But the comparisons sit there in space and time, waiting for us to hear them resonate.

A short Bibliography on Achilles and Agamemnon in Iliad 19

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Barker, Elton and Christensen, Joel. “Even Heracles had to die: Homeric « heroism », mortality and the epic tradition.” Trends in Classics, vol. 6, no. 2, 2014, pp. 249-277.

Deborah Beck. Homeric Conversation. Washington, D.C.: Center for Hellenic Studies, 2005.

Bolter, J. D.. Achilles' return to battle. A structural study of Books 19-22 of the Iliad. Univ. of North Carolina Chapel Hill, 1977.

Christensen, Joel P.. “« Eris » and « epos »: composition, competition, and the domestication of strife.” Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic, vol. 2, 2018, pp. 1-39. Doi: 10.1163/24688487-002010

Davies, Malcolm. “Agamemnon's apology and the unity of the Iliad.” Classical Quarterly, vol. 45, no. 1, 1995, pp. 1-8. Doi: 10.1017/S000983880004163X

Davies, Malcolm. “« Self-consolation » in the « Iliad ».” Classical Quarterly, N. S., vol. 56, no. 2, 2006, pp. 582-587. Doi: 10.1017/S0009838806000553

Gazis, George Alexander. Homer and the poetics of Hades. Oxford: Oxford University Pr., 2018.

Heath, John. “Prophetic horses, bridled nymphs: Ovid's metamorphosis of Ocyroe.” Latomus, vol. 53, 1994, pp. 340-353.

Johnston, Sarah Iles. “Xanthus, Hera and the Erinyes : (Iliad 19.400-418).” TAPA, vol. CXXII, 1992, pp. 85-98.

Dieter Lohmann. Die Komposition der Reden in der Ilias. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1970.

Richard P. Martin. The Language of Heroes: Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989.

Postlethwaite, Norman. “Akhilleus and Agamemnon: generalized reciprocity.” Reciprocity in ancient Greece. Eds. Gill, Christopher, Postlethwaite, Norman and Seaford, Richard A. S.. Oxford: Clarendon Pr., 1998. 93-104.

Rinon, Yoav. “A tragic pattern in the « Iliad ».” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. 104, 2008, pp. 45-91.

Strauss Clay, Jenny. “Agamemnon's stance: (Iliad 19. 51-77).” Philologus, vol. 139, no. 1, 1995, pp. 72-75.

Donna F. Wilson. Ransom, Revenge, and Heroic Identity in the Iliad. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.