This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 23. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 23, as I discuss in the first post, revisits political and heroic themes from books 1 and 2 and offers an opportunity for the epic’s participants and audience alike to reconsider issues of honor, distribution, and institutional order through Achilles’ chairmanship of the funeral games for Patroklos. Often these games are seen as “filler” or a digression following the violence and deaths of books 20-23; but as many others have noted, the whole book is a matter of ritual performance with deep ties both to the material experiences of ancient audiences and to myth in general.

One of the harder things for modern audiences to sense is the extent to which Patroklos’ death in the Iliad is anticipation of or in surrogacy for Achilles’ outside of the Iliad (usually located in the lost cyclic poem the Aethiopis). As I have written about before, I get a little nervous about some of the approaches that fall under the scholarly rubric of “neoanalysis”—the general approach that explores how the Iliad relates to ‘prior’ or, in better cases, ‘other’ narrative traditions. It makes me anxious because, while in its best form it can provide us with an idea of how the Iliad absorbs and responds to other motifs and stories, it too often provides the impression of hierarchical relationships between tales and that certain episodes were fixed in specific ‘poems’ to which ancient audiences had access.

There’s a lot of uncertainty in such assumptions about the relationship among various narratives and what audiences knew. When it comes to the funeral games in particular, this approach surfaces because they are often seen as an echo/doubling/recapitulation of/model for the funeral games for Achilles. As a general rule, I am not opposed to the idea that there is a significant relationship between the episodes, I just think it more likely that an epic grammar of funeral games developed around retelling of tales that centered the death of a great hero and, further, that the depictions of the burial honors for Patroklos and Achilles were so interdependent in their development over time that any ancient audience member would be hard-pressed to articulate clearly where one began and another ended.

This presupposes the timelessness of performance, the space that is created outside a hierarchy of what story was told when by the ever pressing now of the story being told. I think part of the power of the Iliad’s funeral games resides in how much we understand them as anticipating Achilles’ own death and burial. But given how much Achilles is central in the games and how thorough the political theme is, it is really hard to imagine how to evaluate this power. We would need to know what audiences knew, and that is at some level impossible.

Before we get to the games, however, we have the issue of the burial itself. One of the surprising things about book 23 is its setup: most people remember the elaborate games; I think far fewer remember clearly the continued mutilation of Hektor’s body at the book’s beginning, the slaughter of the 12 Trojan youths, or Patroklos appearing as a ghost to chide Achilles for not burying him already.

Homer, Iliad 23.59-92

Peleus’ son was lying there on the strip of the much-resounding sea,

Groaning deeply among the many Myrmidons,

In a cleared space where the waves were lapping at the sand.

There sleep found him, softening the concerns in his heart,

Once it fell around him, sweet. His powerful limbs were exhuasted

From chasing Hektor toward windy Troy.

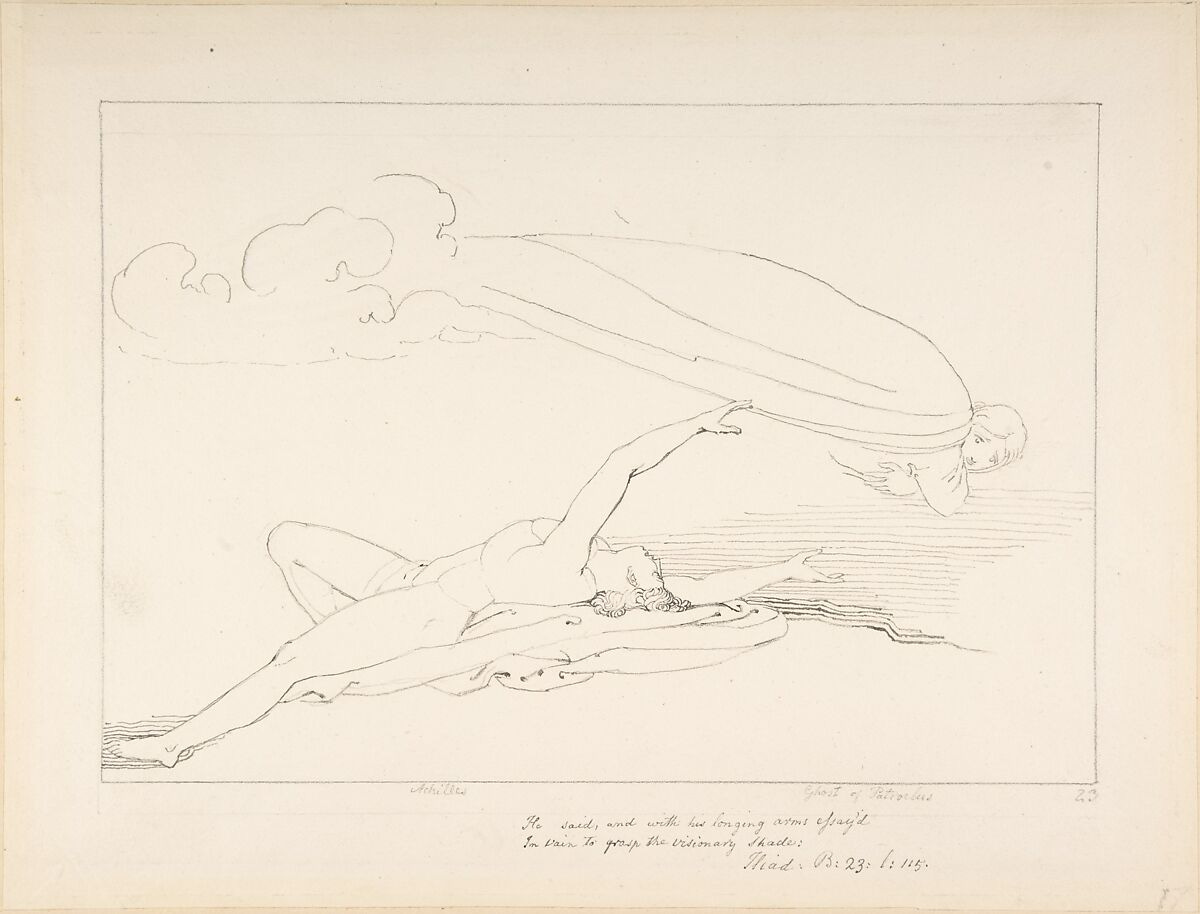

Then the soul of pitiful Patroklos arrived

Alike to himself in every way, in size and his beautiful eyes-

His voice too, and he had similar clothes enveloping him.

He stood above Achilles’ head and addressed him.

“You are sleeping? Then you have forgotten me, Achilles.

You were never careless when I was alive, but now I am dead.

Bury me as quickly as possible so I can enter Hades’ gates.

The souls, those little ghosts of worn out men, are holding me far off—

They will not allow me to join them beyond the river at all,

But I am wandering like this through the home of wide-gated Hades.

Give me your hand too. I am in sorrow, since I will never again

Return from Hades, once you have granted me fire.

We will never again sit alive, apart from our dear companions,

Making our own plans together. Now a hateful fate has

Swallowed me whole, the allotment given as I was born.

This is your fate too, Achilles, even though you are like the gods,

To die in front of the walls of the wealthy Trojans.

But I am going to tell you something, I’ll ask you, if you’ll listen.

Don’t keep my bones apart from yours, Achilles,

But just as we were raised together in your home,

When I was just a young child and Menoitios send me

From Opoeis to your home because of a painful murder,

On that day when I killed the son of Aphidamas, the fool I was,

I did it unwillingly, sent into a rage over a game of dice.

Then the horseman Peleus welcomed me into your home

And raised me in a kind way and named me your attendant.

So have one vessel safeguard our bones together,

A golden chamber with two handles, the one your mother gave you.”ἦλθε δ’ ἐπὶ ψυχὴ Πατροκλῆος δειλοῖο

πάντ’ αὐτῷ μέγεθός τε καὶ ὄμματα κάλ’ ἐϊκυῖα

καὶ φωνήν, καὶ τοῖα περὶ χροῒ εἵματα ἕστο·

στῆ δ’ ἄρ’ ὑπὲρ κεφαλῆς καί μιν πρὸς μῦθον ἔειπεν·

εὕδεις, αὐτὰρ ἐμεῖο λελασμένος ἔπλευ ᾿Αχιλλεῦ.

οὐ μέν μευ ζώοντος ἀκήδεις, ἀλλὰ θανόντος·

θάπτέ με ὅττι τάχιστα πύλας ᾿Αΐδαο περήσω.

τῆλέ με εἴργουσι ψυχαὶ εἴδωλα καμόντων,

οὐδέ μέ πω μίσγεσθαι ὑπὲρ ποταμοῖο ἐῶσιν,

ἀλλ’ αὔτως ἀλάλημαι ἀν’ εὐρυπυλὲς ῎Αϊδος δῶ.

καί μοι δὸς τὴν χεῖρ’· ὀλοφύρομαι, οὐ γὰρ ἔτ’ αὖτις

νίσομαι ἐξ ᾿Αΐδαο, ἐπήν με πυρὸς λελάχητε.

οὐ μὲν γὰρ ζωοί γε φίλων ἀπάνευθεν ἑταίρων

βουλὰς ἑζόμενοι βουλεύσομεν, ἀλλ’ ἐμὲ μὲν κὴρ

ἀμφέχανε στυγερή, ἥ περ λάχε γιγνόμενόν περ·

καὶ δὲ σοὶ αὐτῷ μοῖρα, θεοῖς ἐπιείκελ’ ᾿Αχιλλεῦ,

τείχει ὕπο Τρώων εὐηφενέων ἀπολέσθαι.

ἄλλο δέ τοι ἐρέω καὶ ἐφήσομαι αἴ κε πίθηαι·

μὴ ἐμὰ σῶν ἀπάνευθε τιθήμεναι ὀστέ’ ᾿Αχιλλεῦ,

ἀλλ’ ὁμοῦ ὡς ἐτράφημεν ἐν ὑμετέροισι δόμοισιν,

εὖτέ με τυτθὸν ἐόντα Μενοίτιος ἐξ ᾿Οπόεντος

ἤγαγεν ὑμέτερον δ’ ἀνδροκτασίης ὕπο λυγρῆς,

ἤματι τῷ ὅτε παῖδα κατέκτανον ᾿Αμφιδάμαντος

νήπιος οὐκ ἐθέλων ἀμφ’ ἀστραγάλοισι χολωθείς·

ἔνθά με δεξάμενος ἐν δώμασιν ἱππότα Πηλεὺς

ἔτραφέ τ’ ἐνδυκέως καὶ σὸν θεράποντ’ ὀνόμηνεν·

ὣς δὲ καὶ ὀστέα νῶϊν ὁμὴ σορὸς ἀμφικαλύπτοι

χρύσεος ἀμφιφορεύς, τόν τοι πόρε πότνια μήτηρ.

The sequence of events that leads up to this speech is remarkable enough that a scholiast felt the need to comment on the sudden change. At one moment, we are witnessing Achilles mourning on the sea, and then he is asleep and a dream is looming over him.

Schol. bT ad Hom. Il. 23.65a

“The sudden change is credible: for, after Achilles’ lamentations, the poet has devised something rather new, and he has provided words for someone who died through a dream.”

πιθανὴ ἡ περιπέτεια· μετὰ γὰρ τοὺς ᾿Αχιλλέως θρήνους ἐξεῦρέ τι καινότερον, καὶ τῷ τετελευτηκότι λόγους περιτιθεὶς διὰ τοῦ ὀνείρου.

The language the scholiast uses here—peripateia—is reminiscent of the terminology Aristotle uses for tragedy. In Greek drama, from an Aristotelian perspective, the peripateia is a reversal, a sudden inversion of fate or outcomes that (sometimes) drives audience and/or character towards a recognition (anagnorisis). The sudden turnabout here is nearly akin to a divine intervention. Patroklos appears, but as George Gazis notes, he is not an envoy of the dead in the same way that is represented in book 11 of the Odyssey. Instead, he appears as a dream. The immediacy of it and the rapid transition leaves us little time to think about the other dream in the Iliad, the false dream sent by Zeus in book 2 to persuade Agamemnon to lead his people to war that day (in part to honor Achilles’ request and advance the ‘plan’ of the Iliad).

I bring up that first dream for thematic and structural reasons. Thematically, dreams elsewhere are sent by the gods. Here, we have no agent, no spoken reason. Unbidden, a supernatural force appears to Achilles and confirms his course of action, providing additional information to the audience. It is tempting to read this, as some do, as an exploration of Achilles’ guilt rather than a literal ghost in a dream; but the vividness and detail leads me to believe that ancient audiences would have taken this as a literal dream. Again, thematically, this makes sense for where we are in the epic.

Dreams and sleep are often paired in early Greek myth as moving between the realms of the seen (the world of the living/day) and the unseen (the underworld/night). Achilles, moreover, has been depicted directly and indirectly as separated from the realm of the living, so much so that when Priam travels to meet him in Iliad 24, he is guided by Hermes, whose role as the psychopompos (the “marshal of souls”) is to guide the dead to Hades’ realm. Perhaps we can imagine Achilles in a space where the fabric between the realms is thinning, frayed, and Patroklos can reach him thanks to their indelible bond, stretching across life’s final boundary.

(Although, to be fair, this sounds a bit too much like a tagline for the movie Ghost.)

Whether we see Patroklos as an actual ghost or an outlet for Achilles’ conscience, the speech provides some background for their relationship and an implicit critique of Achilles. The story Patroklos tells about how they came to know one another is explained in another scholion.

Schol. D ad Il. 12.1 [see Apollodorus 3.13.8]

“Menoitios’ son Patroklos grew up in Opos in Locris but was exiled for an involuntary mistake. For he killed a child his age, the son of the memorable Amphidamas Kleisonumos, or, as some say, Aianes, because he was angry over dice. He went to Phthia in exile for this crime and got to know Achilles there because of his kinship with Peleus. They cemented a deep friendship with one another before they went on the expedition against Troy. This story is from Hellanicus.”

Μενοιτίου ἄλκιμος υἱός] Πάτροκλος ὁ Μενοιτίου τρεφόμενος ἐν ᾿Οποῦντι τῆς Λοκρίδος περιέπεσεν ἀκουσίωι πταίσματι· παῖδα γὰρ ἡλικιώτην ᾿Αμφιδάμαντος οὐκ ἀσήμου Κλ<ε>ισώνυμον, ἢ ὥς τινες Αἰάν<ην>, περὶ ἀστραγάλων ὀργισθεὶς ἀπέκτεινεν· ἐπὶ τούτωι δὲ φυγὼν εἰς Φθίαν ἀφίκετο, κἀκεῖ κατὰ συγγένειαν Πηλέως ᾿Αχιλλεῖ συνῆν. φιλίαν δὲ ὑπερβάλλουσαν πρὸς ἀλλήλους διαφυλάξαντες ὁμοῦ ἐπὶ ῎Ιλιον ἐστράτευσαν. ἡ ἱστορία παρὰ ῾Ελλανίκωι.

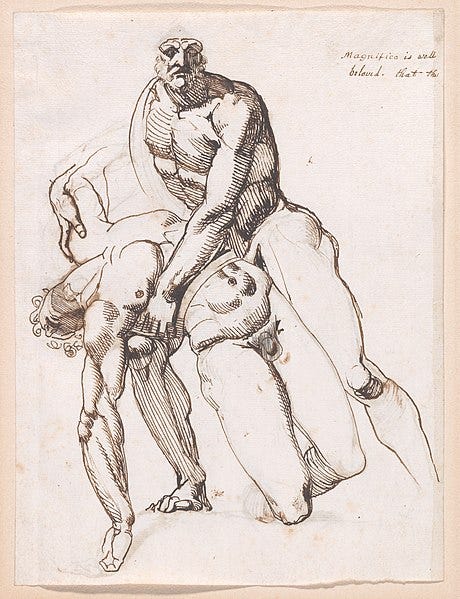

The detail I think is really interesting here and in the speech is that Achilles and Patroklos were brought together by a rage-induced mistake that shattered one community only to create a new one. Patroklos starts out by telling Achilles that he is still suffering, that he cannot rest because Achilles has not cared for his body. Achilles’ rage, then, has been entirely for himself. It had no hope of raising the dead and only has increased the amount of bodies to be buried.

Patroklos reminds Achilles of his own story only after he asks him to make sure that their bones are interred together in one vessel. When he reminds Achilles of how they came to be together, he uses a thematic word for anger (kholôtheis) that should remind audiences of all the damage anger has done in the Iliad’s world. I suspect that Patroklos’ story redounds on Achilles as well, inviting him (and us) to think about the other actions undertaking “unwillingly” and their outcomes, the way Achilles’ anger led him to pray for his people to suffer, the way his people suffering meant Patroklos’ death too.

The point, I think, is an analogical one: the union in death following rage and its ruin is a remaking of life, but in a final fashion. Just as Patroklos’ childhood error led to an adolescent life with Achilles, so too will Achilles’ adult mistake still lead to a kind of eternal life with Patroklos. It is a small solace and no replacement for a life together, but it is something. And it is something Achilles, now, has to create on his own. If there is a peripateia in this moment, it is to be found both in the plot (a move from lament to action) and in the character who drives the plot.

The blending of the Achilles and Patroklos in death—both through the metaphorical overlapping of tales and the literal blending of bones—should remind us of the powerful themes of surrogacy that bind Achilles and Patroklos further together. In this near-final articulation, however, I wonder how much we need to consider Achilles response and the subtle narrative revelation that Achilles reached out to him, but could not grab him, because his spirit “like smoke”. Achilles’ request for an embrace is unfulfilled, yet he turns almost immediately to start the process of burial.

One of the things I emphasize when talking about Achilles’ amazing second lament for Patroklos is that he still seems to be expressing his own sense of loss primarily. This is, of course, a realistic representation of grieving and I may be mistaken in believing that it is only a step toward a broader sense of loss in the world. When my father died suddenly at 61, I don’t know that I started to grieve for what he lost until years later and it was prompted mostly by feelings of joy, tempered by his absence. In times of loss I have come to think more about what the missing miss out on: for my father and his mother, getting to see my children born and grow, taking joy at their joy in the world, and comfort with a world born anew through them.

In my reading of the multiple audiences to Achilles’ speech about his disappointed expectation that Patroklos would be the one to live on and take his place in the world, I think the Iliad is anticipating the epic’s end, when Achilles ever so briefly sees Priam as real through their intersecting yet separate pain. Part of the point of dramatic narrative, I think, is to give us an access to a world outside ourselves, to help us fill our bodies and minds with others’ light and love, both so we can be more unto ourselves and we can make a better world alongside others because we know they are real.

But even this approach, as magnanimous as it might sounds, runs the risk of instrumentalizing others’ pain for the sake of individual gain. Just as easily as someone can mourn what a loved one misses out on, we could take the opposite corollary, to celebrate all they will not suffer. Such a pessimistic view is not far off from the so-called “wisdom of Silenus,” that the best fortune is not to live long or die in glory, but never to have been at all.

And yet, for all it’s apparent logic, this seems too bleak. An epic so invested in showing us the power of loss, can’t possibly be telling us that a superior alternative is never feeling love at all.

A short Bibliography on the Ghost of Patroklos

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Anderson, Warren D. “Achilles and the Dark Night of the Soul.” The Classical Journal 51, no. 6 (1956): 265–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3292885.

Arft, J., and J. M. Foley. 2015. “The Epic Cycle and Oral Tradition.” In Fantuzzi and Tsagalis, 78–95.

Emily P. Austin, Grief and the hero: the futility of longing in the Iliad. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021.

Jonathan Burgess. The Tradition of the Trojan War in Homer and the Epic Cycle. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Fantuzzi, M. 2012. Achilles in Love. Oxford.

Devereux, George. “Achilles' «suicide » in the Iliad.” Helios, vol. VI, no. 2, 1978-1979, pp. 3-15.

G

azis, George Alexander, 'The Dream of Achilles', Homer and the Poetics of Hades (Oxford, 2018; online edn, Oxford Academic, 24 May 2018), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198787266.003.0003, accessed 19 Mar. 2024.

Lesser, Rachel. 2022. Desire in the Iliad: The Force That Moves the Epic and Its Audience. Oxford.

Lowenstam, Steven. “Patroclus' death in the Iliad and the inheritance of an Indo-European myth.” Archaeological News, vol. VI, 1977, pp. 72-76.

Mouratidis, Ioannis. “Anachronism in the Homeric games and sports.” Nikephoros, vol. III, 1990, pp. 11-22.

MUELLNER, L. Metonymy, Metaphor, Patroklos, Achilles. Classica: Revista Brasileira de Estudos Clássicos, [s. l.], v. 32, n. 2, p. 139–155, 2019. DOI 10.24277/classica.v32i2.884

Mylonas, George E. “Homeric and Mycenaean Burial Customs.” American Journal of Archaeology 52, no. 1 (1948): 56–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/500553.

Paschalis, Sergios. “The Epic Hero as Sacrificial Victim: Patroclus and Palinurus.” Hermathena, no. 199 (2015): 135–58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26921696.

Rengakos, Antonios. “Aethiopis.” The Greek Epic Cycle and its ancient reception : a companion. Eds. Fantuzzi, Marco and Tsagalis, Christos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pr., 2015. 306-317.

Roller, Lynn E. “Funeral Games in Greek Art.” American Journal of Archaeology 85, no. 2 (1981): 107–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/505030.

Russo, Joseph. "The Ghost of Patroclus and the Language of Achilles". Euphrosyne: Studies in Ancient Philosophy, History, and Literature, edited by Peter Burian, Jenny Strauss Clay and Gregson Davis, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2020, pp. 209-222. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110605938-012

Warwick, C. (2019). We Two Alone: Conjugal Bonds and Homoerotic Subtext in the Iliad. Helios 46(2), 115-139. https://doi.org/10.1353/hel.2019.0007.

Malcolm M. Willcock, ‘The funeral games of Patroclus’, Proceedings of the Classical Association, LXX. (1973) 36.