This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations. Don’t forget about Storylife: On Epic, Narrative, and Living Things. Here is its amazon page. here is the link to the company doing the audiobook and here is the press page.

I missed a week of posting, thanks to a whirlwind of work and a trip to Winnipeg, Canada to present a talk at the Classical Association of Canada Annual Meeting. To make up for the skipped week, I will present the talk here in three parts. . The First part, on Violence and Lament, is here. For the second part, A Theoretical Interlude, go here.

Priam and Achilles

In book 24, Priam’s journey to Achilles invokes a liminal space between life and death. This space is also one where the regular boundaries between nations and peoples may not apply—a zone potentially open to different ways of engaging and viewing the world. How this scene achieves its impact informs how epic works in general and can answer why Aristotle thinks the Iliad is the most tragic of epics, not in form but in function and effect. So far, I have talked about the family-rending violence anticipated in book 6, the way laments in book 19 invite us to see witnesses to suffering understanding it by making comparison to their own lives. I have offered a simple framework of blending to explain how the structure of archaic poetry supports this. I want to turn now to the epic’s end, to think about concepts from tragedy like recognition and identification, and why the Iliad emphasizes the difficulty of Achilles’ final scene.

Homer, Iliad 24.477-512

Great Priam escaped the notice of [Achilles’ companions] when he entered the room

And he stood right next to him, clasping his knees and kissing his hands

Those terrible [deinas] murderous hands that had killed so many of his sons.

As when bitter ruin overcomes someone who killed a man

In his own country and goes to the land of others

To some rich man, and wonder [thambos] over takes those who see him.

So too did Achilles feel wonder [thambêsen] when he saw godlike Priam.

The rest of the people there were shocked [thambêsan] and they all looked at one another

Then Priam was begging as he addressed him.

“Divine Achilles, remember [mnêsai] your father—

The same age as I am, on the deadly threshold of old age.

The people who live around him are wearing him out,

I imagine, and there is no one there to ward off conflict and disaster.

But when that man hears that you are alive still,

He rejoices in his heart because he will keep hoping all his days

That he will see his dear son again when he comes home from Troy.

But I am completely ruined. I had many of the best sons

In broad Troy, but I think that none of them are left.

I had fifty sons when the sons of the Achaeans arrived here.

Nineteen of them were mine from the same mother,

And other women bore the rest to me in my home.

Rushing Ares loosened the limbs of many of them,

But the one who was left alone for me, who defended the city and its people

You killed as he warded danger from his fatherland,

Hektor, for whom I have home now to the Achaeans’ ships

To ransom him from you. And I am bringing endless exchange gifts.

But feel fame before the gods, Achilles, and pity [eleêson] him

Once you have remembered [mnsêsamenos] your father. I am more pitiful [eleeinoteros] still,

I who suffer what no other mortal on this earth has ever suffered,

putting the hand of the man who murdered my son to my mouth.’

So Priam spoke and a desire for mourning his father rose within him.

He took his hand and pushed the old man gently away.

The two of them remembered [tô mnêsamenô]: one wept steadily

For man-slaying Hektor, as he bent before Achilles’ feet,

But Achilles’ was mourning his own father, and then in turn

Patroklos again—and their weeping rose throughout the home.”τοὺς δ’ ἔλαθ’ εἰσελθὼν Πρίαμος μέγας, ἄγχι δ’ ἄρα στὰς

χερσὶν ᾿Αχιλλῆος λάβε γούνατα καὶ κύσε χεῖρας

δεινὰς ἀνδροφόνους, αἵ οἱ πολέας κτάνον υἷας.

ὡς δ’ ὅτ’ ἂν ἄνδρ’ ἄτη πυκινὴ λάβῃ, ὅς τ’ ἐνὶ πάτρῃ

φῶτα κατακτείνας ἄλλων ἐξίκετο δῆμον

ἀνδρὸς ἐς ἀφνειοῦ, θάμβος δ’ ἔχει εἰσορόωντας,

ὣς ᾿Αχιλεὺς θάμβησεν ἰδὼν Πρίαμον θεοειδέα·

θάμβησαν δὲ καὶ ἄλλοι, ἐς ἀλλήλους δὲ ἴδοντο.

τὸν καὶ λισσόμενος Πρίαμος πρὸς μῦθον ἔειπε·

μνῆσαι πατρὸς σοῖο θεοῖς ἐπιείκελ’ ᾿Αχιλλεῦ,

τηλίκου ὥς περ ἐγών, ὀλοῷ ἐπὶ γήραος οὐδῷ·

καὶ μέν που κεῖνον περιναιέται ἀμφὶς ἐόντες

τείρουσ’, οὐδέ τίς ἐστιν ἀρὴν καὶ λοιγὸν ἀμῦναι.

ἀλλ’ ἤτοι κεῖνός γε σέθεν ζώοντος ἀκούων

χαίρει τ’ ἐν θυμῷ, ἐπί τ’ ἔλπεται ἤματα πάντα

ὄψεσθαι φίλον υἱὸν ἀπὸ Τροίηθεν ἰόντα·

αὐτὰρ ἐγὼ πανάποτμος, ἐπεὶ τέκον υἷας ἀρίστους

Τροίῃ ἐν εὐρείῃ, τῶν δ’ οὔ τινά φημι λελεῖφθαι.

πεντήκοντά μοι ἦσαν ὅτ’ ἤλυθον υἷες ᾿Αχαιῶν·

ἐννεακαίδεκα μέν μοι ἰῆς ἐκ νηδύος ἦσαν,

τοὺς δ’ ἄλλους μοι ἔτικτον ἐνὶ μεγάροισι γυναῖκες.

τῶν μὲν πολλῶν θοῦρος ῎Αρης ὑπὸ γούνατ’ ἔλυσεν·

ὃς δέ μοι οἶος ἔην, εἴρυτο δὲ ἄστυ καὶ αὐτούς,

τὸν σὺ πρῴην κτεῖνας ἀμυνόμενον περὶ πάτρης

῞Εκτορα· τοῦ νῦν εἵνεχ’ ἱκάνω νῆας ᾿Αχαιῶν

λυσόμενος παρὰ σεῖο, φέρω δ’ ἀπερείσι’ ἄποινα.

ἀλλ’ αἰδεῖο θεοὺς ᾿Αχιλεῦ, αὐτόν τ’ ἐλέησον

μνησάμενος σοῦ πατρός· ἐγὼ δ’ ἐλεεινότερός περ,

ἔτλην δ’ οἷ’ οὔ πώ τις ἐπιχθόνιος βροτὸς ἄλλος,

ἀνδρὸς παιδοφόνοιο ποτὶ στόμα χεῖρ’ ὀρέγεσθαι.

῝Ως φάτο, τῷ δ’ ἄρα πατρὸς ὑφ’ ἵμερον ὦρσε γόοιο·

ἁψάμενος δ’ ἄρα χειρὸς ἀπώσατο ἦκα γέροντα.

τὼ δὲ μνησαμένω ὃ μὲν ῞Εκτορος ἀνδροφόνοιο

κλαῖ’ ἁδινὰ προπάροιθε ποδῶν ᾿Αχιλῆος ἐλυσθείς,

αὐτὰρ ᾿Αχιλλεὺς κλαῖεν ἑὸν πατέρ’, ἄλλοτε δ’ αὖτε

Πάτροκλον· τῶν δὲ στοναχὴ κατὰ δώματ’ ὀρώρει.

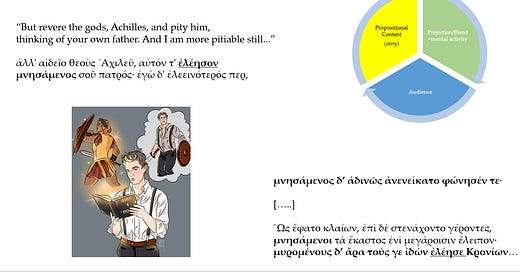

The language of the encounter between Achilles and Priam resonates with the framing I emphasized from the laments in book 19. Many of the words also signal poetic creation/memory (words of remembering) in setting up a parallel (Priam relating his loss to Achilles’ father’s potential loss; both heroes seeing their own pain in another). Note as well the affective emphasis in the passage and the set-up, in particular on feelings of “pity” and “wonder” or ‘fear”. Wonder/surprise is operative in characterizing Achilles’ response and his ability to feel pity, which in this context seems to correlate to what happens in the narrative, which is that Priam and Achilles together engage in an act of remembering that stems from a shared performance (Priam’s speech) but extends to their individual experiences and a very real difference in the way they internally narrativize their brief common ground.

There is a repeated emphasis on pity. Prior to the supplication, Hermes provides Priam with very specific instructions (Iliad 24.354-357) And this follows an invocation Zeus sending Hermes to Priam because he pitied him (“When [Zeus] saw the old man, he pitied him and / Quickly addressed his own son Hermes...”, ἐς πεδίον προφανέντε· ἰδὼν δ' ἐλέησε γέροντα, / αἶψα δ' ἄρ' ῾Ερμείαν υἱὸν φίλον ἀντίον ηὔδα, 24.354-57). Recall how the women who grieve for Patroklos turn from him to their own pains (῝Ως ἔφατο κλαίουσ’, ἐπὶ δὲ στενάχοντο γυναῖκες / Πάτροκλον πρόφασιν, σφῶν δ’ αὐτῶν κήδε’ ἑκάστη, 19.302-303), then Achilles himself moves from topic to topic, comparing his loss in one instance to other possible losses, finally inspiring the other old men to mourn along with him, using his pain as kindling for their own fires of memory and loss.

That earlier passage helps us see as well how Achilles’ grief is metonymic for his own loss and others as well. Achilles’ grief presents a narrative others see themselves in, they project their experiences into his pain and grieve alongside him. Lament becomes a way of recuperating community through not just despite loss. The exchange between Priam and Achilles is the culmination of this narrative arc and it has individual ramifications as well as potential information for how we should understand the epic genre. Central to this movement is the sustained importance of pity. Scholars have taken different approaches to this. Dean Hammer (2002) has emphasized how Achilles’ view of his relation to other dominates his “ethical stance”, arguing for a transformation that allows him to feel pity for Priam because his experiences within the epic have changed how he views suffering. Graham Zanker makes a similar argument in The Heart of Achilles where he suggests that it is important that Achilles came to this change on his own, that the gods did not support him: His present behavior is therefore a pole apart from his cruel rejection of the supplications of men like Tros, Lykaon, and Hektor. Homeric theology allows Achilles' present generosity, or rather magnanimity, to be based on his own volition” (Zanker 1996, 120). Jinyo Kim’s full study The Pity of Achilles traces the language of pity throughout the Iliad to demonstrate that this theme supports the epic’s unity. For Kim, “Achilles’ pity for Priam constitutes no incidental detail, but is instead the thematic catalyst of the reconciliation’ (2000, 12).

I agree with all of this. But I think there’s more to be found in the model of experiencing others’ grief as your own and its connection to how the epic conceives of our reaction to stories. I earlier used the word ‘dramatize’ and not accidentally: there’s something of tragic performance to this function. Marjolein Oele (2011) has suggested that when Priam and Achilles cry together they come to identify with each other in a way that anticipates Aristotle’s comments throughout his work—their unique moment isn’t merely pity, but instead it is a shared experience of suffering and wonder that helps them accomplish what Aristotle would call recognition. Here I want to pause to make a semantic and clinical distinction: any emotion or expression there of is rooted in social contexts.

Pity in English too often has a pejorative valence–it conveys a power structure as well as a sense of superiority, even contempt. But I think the pity signaled here in the Iliad is one of sympathetic remorse, rooted in the very nature of recognition and identification. While most scholars see some relationship between the dramatic personae of epic and tragic performances (see especially Irene J. F. De Jong’s 2016 essay, Stroud and Robertson’s essay, or Emily Allen-Hornblower’s 2015 book), I think there has been less focus on the affective impact modeled within epic poetry. Epic’s gradual but persistent emphasis on generative and combinatory acts of memory as loci for exploring one’s own experiences in a shared common frame reminds me as well of Aristotle’s famous focus on “pity and fear”. Consider again the emotions evoked during book 24: wonder, pity, fear.

Aristotle, Poetics 1449b21-27

“We’ll talk later about mimesis in hexameter poetry and comedy. For now, let’s chat about tragedy, starting by considering the definition of its character based on what we have already said. So, tragedy is the imitation (mimesis) of a serious event that also has completion and scale, presented in language well-crafted for the genre of each section, performing the story rather than telling it, and offering cleansing (catharsis) of pity and fear through the exploration of these kinds of emotions.”

Περὶ μὲν οὖν τῆς ἐν ἑξαμέτροις μιμητικῆς καὶ περὶ κωμῳδίας ὕστερον ἐροῦμεν· περὶ δὲ τραγῳδίας λέγωμεν ἀναλαβόντες αὐτῆς ἐκ τῶν εἰρημένων τὸν γινόμενον ὅρον τῆς οὐσίας. ἔστιν οὖν τραγῳδία μίμησις πράξεως σπουδαίας καὶ τελείας μέγεθος ἐχούσης, ἡδυσμένῳ λόγῳ χωρὶς ἑκάστῳ τῶν εἰδῶν ἐν τοῖς μορίοις, δρώντων καὶ οὐ δι᾿ ἀπαγγελίας, δι᾿ ἐλέου καὶ φόβου περαίνουσα τὴν τῶν τοιούτων παθημάτων κάθαρσιν.

There are several other passages throughout his work where Aristotle adds to his conceptualization to include reversal (peripateia) and recognition (anagnorisis), but in the steady focus on memory/narrative (mimesis and memory), as well as the experience of pity and fear/wonder I have highlighted in book 24, I see a much stronger tragic/dramatic potential within Homer. And this is supported in part by one of the few scenes we have from the 4th century that describes the work of a rhapsode, a performer of Homeric poetry. In his dialogue, the Ion, Plato has his rhapsode describe what he feels and sees when performing Homer

Plato, Ion 535d-e

Ion: Now this proof is super clear to me, Socrates! I’ll tell you without hiding anything: whenever I say something pitiable [ἐλεεινόν τι], my eyes fill with tears. Whenever I say something frightening [φοβερὸν ἢ δεινόν], my hair stands straight up in fear and my heart leaps!

Socrates: What is this then, Ion? Should we say that a person is in their right mind when they are all dressed up in decorated finery and gold crowns at the sacrifices or the banquets and then, even though they haven’t lost anything, they are afraid still even though they stand among twenty thousand friendly people and there is no one attacking him or doing him wrong?

Ion: Well, by Zeus, not at all, Socrates, TBH.

Socrates: So, you understand that you rhapsodes produce the same effects on most of your audiences?

Ion: Oh, yes I do! For I look down on them from the stage at each moment to see them crying and making terrible expressions [δεινὸν], awestruck [συνθαμβοῦντας] by what is said. I need to pay special attention to them since if I make them cry, then I get to laugh when I receive their money. But if I make them laugh, then I’ll cry over the money I’ve lost!”

Note how Ion uses language we see in the Iliad itself and the passage where Priam and Achilles meet. Where the internal evidence of epic shows its own audiences (the women, the old men, and Zeus) internalizing and responding to the narrative, Plato’s Ion features a performer expecting the same kinds of reactions from his audience (even if for less than noble reasons). When it comes to pity in particular, Emily Allen-Hornblower suggests that “The emotional charge that comes with the act of watching a loved one suffer (or die) is directly apparent in the phraseology of the Iliad...” (2015, 26) and later that Achilles’ position as a spectator during most of the epic is an important part of his development. This provides, to me, another signal of what epic audiences were expected to be doing: watching, listening, feeling, and changing in turn. Yet, there is a tension between epic as something to passively feel about and epic as a call to action. Another way to parse pity is the difference between empathy and sympathy, or, as some bioethicists have posed it, pity that enables action or pity that limits it. Empathy is feeling something like what someone else does; sympathy is sometimes described as a third person perspective, one that motivates actions based on concerns for another’s suffering. A larger question, but is the impact of mimetic art primarily aesthetic and personal, or is it ethical and communal?

I think the Iliad expects people to respond to suffering with pity that reminds them of their own suffering–empathy; second, I think the epic models this process as something that is potentially humanizing, creating a community of care where others’ experiences matter, sympathy, even if it is not necessarily so; third, I think the dramatic scope within the epic combined by some evidence for similar expectations outside the epic helps to support both a dynamic model of reading for Homer itself and also a shared performative ground for epic and ancient tragedy, helping to provide a different reason for why the Iliad is the most tragic of ancient epics.

Becoming Human

The Iliad is in part the story of ‘civilizing’ conventions of wars dismissed. What we learn from the beginning is that political institutions are not strong enough to enforce the maintenance of normative behaviors. The personal decisions of individuals–Paris before the war, Agamemnon at the beginning of the Iliad–run roughshod across principles of ransom in exchange for life that the assembled Greeks cheer for in book 1. Empathy seems here to fail; only to be reasserted after suffering. In a way, this is a restatement of Aristotle’s notion of the benefit of experiencing pity and fear: recognition and identification make it possible for us to see the self in the other. Perhaps, then, we could reposition catharsis as a communal recuperation of empathy.

But then, what can we say of the effect of art aimed to humanize? The very audiences who enjoyed the Iliad engaged in monumental violence like that in the reduction of Melos during the Peloponnesian War. The story of excessive violence in the Iliad is that of the rejection of conventions meant to make war in some way predictable and ‘acceptable’ to the combatants. The planned sexual violence of the Achaeans, the rejection of ransom-exchange, and the promotion of infanticide all come within the frame of the breakdown of political control over individual behavior. ‘Rage’ is the break from limitations enforced by social conventions; it unleashes the true hell of war and unveils the brutal, dehumanizing violence pulsating beneath the service of ‘civilization’. War reduces people to casualty numbers. But dehumanization comes before it: the refusal of reciprocal relationships, the call to eradicate a people, Achilles’ transformation into animal violence, met by the oppressed Hecuba’s wish to eat his liver raw.

Even the epic’s conclusion is compromised: the cessation of Achilles’ rage only comes through monstrous behavior (corpse-disfigurement and human sacrifice) and occurs at the personal level between a bereft father and a surrogate son whose potential for violence has ebbed through exhaustion and divine intervention. It thematically seals the epic’s arc: book 1 saw the breakdown in social convention thanks to the whims of an angry king; book 24 sees the conventions briefly reinforced, thanks to the needs of two kings in despair. Yet their attitude is not one of rejection violence or rehabilitation, but resignation to the continuing war that will take both of their lives.

In his work on human evolution and development, Michael Tomasello has foregrounded a definition of humanity in our communication and collaboration, our “shared mentality” rooted in imitative behavior and social learning alongside the development of what he calls a moral identity. In her recent work, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson shows that this is promise is not universally applied–the very practices of the west that create common culture can also define people out of humanity, by reducing them to objects, by racializing, genderizing, or otherwise categorizing other beings as outside the purview of the moral identity that defines us.

This too is a part of the Iliad’s story and its dramatic impact. The culture, practices, and relationships that define the Achaeans from the epic’s beginning also make it possible for one exceptional figure to instrumentalize, objectify, and reduce others. The poem’s thematic lesson is that once loose in the world, such a reduction in status knows no end: Achilles does not mean for Patroklos to die, but it is a direct result of his own excess and reduction of others to satisfy his story of loss. The poem’s mimetic lesson shows how it takes repeated suffering to comprehend a human world beyond oneself. The premise, I suggest, is that humanization is a process that must always be ongoing. Poetry, performance and art–the humanities–offer this promise, but require patience, observation, identification and community and for its fulfillment.

Selected Bibliography

Allen-Hornblower, Emily. 2015. From agent to spectator : witnessing the aftermath in ancient Greek epic and tragedy, De Gruyter, 2015.

Anderson, Michael J. 1997 The Fall of Troy in Early Greek Poetry and Art Oxford.

Anderson, Warren D. 1956 “Achilles and the Dark Night of the Soul.” The Classical Journal 51, no. 6: 265–68.

Austin, Emily P. 2021. Grief and the hero: the futility of longing in the Iliad. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Burgess, Jonathan. 1997. “Beyond Neo-Analysis: Problems with the Vengeance Theory.” The American Journal of Philology 118, no. 1: 1–19.

Christensen, Joel P. 2025. Storylife, On Epic, Language, and Living things. Yale.

Christensen, Joel P. 2020. The Many-Minded Man: The Odyssey, Psychology, and the Therapy of Epic. Cornell.

Cook, Erwin. 2014. “Structure as Interpretation in the Homeric Odyssey.” In Defining Greek Narrative, edited by Douglas Cairns and Ruth Scodel, 75–102. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

De Jong, Irene. J. F. 2016. ‘Homer : the first tragedian’, Greece and Rome, Ser. 2, 63.2:149-162.

Douglas, Mary. 2007. Thinking in Circles: An Essay on Ring Composition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dué, Casey. Homeric variations on a lament by Briseis. Greek Studies: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Rowman and Littlefield, 2002.

Ebbinghaus, Susanne. 2005. “Protector of the City, or the Art of Storage in Early Greece.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 125: 51–72.

Ervin, M. 1963. “A relief pithos from Mykonos”, Archaiologikon Deltion 18 (1963), pp. 37-75.

Gaca, Kathy L. 2014. “MARTIAL RAPE, PULSATING FEAR, AND THE SEXUAL MALTREATMENT OF GIRLS (Παῖδες), VIRGINS (Παρθένοι), AND WOMEN (Γνναῖκες) IN ANTIQUITY.” The American Journal of Philology 135, no. 3 (2014): 303–57.

Hammer, Dean C. 2002. “The « Iliad » as ethical thinking: politics, pity, and the operation of esteem.” Arethusa, vol. 35, no. 2: 203-235.

Heiden, Bruce. 1998 “The simile of the fugitive homicide, Iliad 24.480-84: analogy, foiling, and allusion.” American Journal of Philology, vol. 119, no. 1, 1998, pp. 1-10.

Jackson, Zakkiyah Iman. 2020. Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World. NYU.

Kim, Jinyo. 2000. The Pity of Achilles: Oral Style and the Unity of the Iliad. Rowman & Littlefield.

Lesser, Rachel. 2022. Desire in the Iliad: The Force That Moves the Epic and Its Audience. Oxford.

Lowenstam, Steven. “Patroclus' death in the Iliad and the inheritance of an Indo-European myth.” Archaeological News, vol. VI, 1977, pp. 72-76.

Lowenstam, Steven. 1981. The Death of Patroclus: A Study in Typology.

Most, Glenn W. “Anger and pity in Homer's « Iliad »’, Yale Classical Studies, 32. (2003) 50-75.

Rinon, Yoav. Homer and the dual model of the tragic. Ann Arbor (Mich.): University of Michigan Pr., 2008.

Rutherford, Richard. “Tragic form and feeling in the Iliad.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. CII, 1982, pp. 145-160.

Marjolein Oele, ‘Suffering, pity and friendship: an Aristotelian reading of Book 24 of Homer’s « Iliad »’, Electronic Antiquity, 14.1 (2010-2011) 15.

Sparkes, B. A. “The Trojan Horse in Classical Art.” Greece & Rome 18, no. 1 (1971): 54–70.

Stroud, T. A., and Elizabeth Robertson. “Aristotle’s ‘Poetics’ and the Plot of the ‘Iliad.’” The Classical World 89, no. 3 (1996): 179–96.

Tomasello, Michael. 2019. Becoming Human: A Theory of Ontogeny. Harvard.

Turner, Mark. 1996. The Literary Mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

Warwick, C. (2019). “The Maternal Warrior: Gender and Kleos in the Iliad.” American Journal of Philology 140(1), 1-28.

Warwick, C. (2019). “We Two Alone: Conjugal Bonds and Homoerotic Subtext in the Iliad. “Helios 46(2), 115-139.

Zanker, Graham. 1996. The Heart of Achilles: Characterization and Personal Ethics in the Iliad. University of Michigan.