This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations. Don’t forget about Storylife: On Epic, Narrative, and Living Things. Here is its amazon page. here is the link to the company doing the audiobook and here is the press page.

There’s a proverb attributed to the Spartan Aristodemus–but also to the poet Alcaeus– “a man is [his] money and no one poor is noble or honored” (χρήματ᾿ ἄνηρ, πένι-/ χρος δ᾿ οὐδ᾿ εἴς πέλετ᾿ ἔσλος οὐδὲ τίμιος; Alcaeus, fragment 360, 3). The line deserves some glossing for those who don’t know a lot of Greek. The ancient word for money here is khrêmata, the plural of the word for “thing”. If we could imagine that this might not mean money the way we imagine it, we could translate this more as “a man is his stuff”, or, more broadly, “you are what you own”.

We don’t actually get this line directly from Alcaeus or Aristodemus, however. It shows up in the epinician poet Pindar and is recording in the scholia to that poet as being proverbial

“Thrasyboulos: people in the past

Used to climb onto the chariot

Of the gold-crowned Muses

Armed with a fame-bringing lyre.

Then they would quickly aim their sweet-voiced hymns

At the boys–whoever was cute and

in that sweetest summer season

Of well-throned Aphrodite.That’s because the Muse wasn’t yet

Too fond of profit nor yet

A working girl.

And sweet songs

From honey-voiced Terpsichore

Weren’t yet sold as pricey tricks.So now she invites us to remember

The word of the Argive that’s closest

To the truth: “Money,

A man is his money”–

As someone claims when he’s lost

His possessions along with his friends.”Οἱ μὲν πάλαι, ὦ Θρασύβουλε,

φῶτες, οἳ χρυσαμπύκων

ἐς δίφρον Μοσᾶν ἔβαι-

νον κλυτᾷ φόρμιγγι συναντόμενοι,

ῥίμφα παιδείους ἐτόξευον μελιγάρυας ὕμνους,

ὅστις ἐὼν καλὸς εἶχεν Ἀφροδίτας

εὐθρόνου μνάστειραν ἁδίσταν ὀπώραν.

ἁ Μοῖσα γὰρ οὐ φιλοκερδής

πω τότ᾿ ἦν οὐδ᾿ ἐργάτις·

οὐδ᾿ ἐπέρναντο γλυκεῖ-

αι μελιφθόγγου ποτὶ Τερψιχόρας

ἀργυρωθεῖσαι πρόσωπα μαλθακόφωνοι ἀοιδαί.νῦν δ᾿ ἐφίητι <τὸ> τὠργείου φυλάξαι

ῥῆμ᾿ ἀλαθείας <⏑–> ἄγχιστα βαῖνον,

“χρήματα χρήματ᾿ ἀνήρ”

ὃς φᾶ κτεάνων θ᾿ ἅμα λειφθεὶς καὶ φίλων.

Here’s the scholion to this poem that explains the repetition χρήματα χρήματ᾿ ἀνήρ.

Schol. Pind. Isthm. 2. 17 (iii 215–16 Drachmann)

“Money, money is the man.” This is counted among proverbs by some, but it is a saying of Aristodemus as Chrysippus reports in his work On Proverbs. Pindar does not name this Aristodemus, but instead makes it clear when he says where he is from, he says only his country, that he is Argive. But Alcaeus names both the man and his country, not Argos but Sparta. For he says that Aristodemos said it smartly in Sparta when he explained, “money is the man, no one poor is noble nor honored”

χρήματα, χρήματ' ἀνήρ: τοῦτο ἀναγράφεται μὲν εἰς τὰς παροιμίας ὑπ' ἐνίων, ἀπόφθεγμα δέ ἐστιν ᾿Αριστοδήμου, καθάπερ φησὶ Χρύσιππος ἐν τῷ περὶ παροιμιῶν. τοῦτον δὲ τὸν ᾿Αριστόδημον Πίνδαρος μὲν οὐ τίθησιν ἐξ ὀνόματος, ὡς προδήλου ὄντος ὅς ἐστιν ὁ τοῦτο εἰπών, μόνον δὲ ἐσημειώσατο τὴν πατρίδα, ὅτι ᾿Αργεῖος· ᾿Αλκαῖος δὲ (fr. 49) καὶ τὸ ὄνομα καὶ τὴν πατρίδα τίθησιν, οὐκ ῎Αργος, ἀλλὰ Σπάρτην· ὣς γὰρ δή ποτέ φασιν ᾿Αριστόδημον ἐν Σπάρτᾳ λόγον οὐκ ἀπάλαμνον εἰπεῖν· χρήματ' ἀνήρ· πενιχρὸς δὲ οὐδεὶς πέλετ' ἐσλὸς οὐδὲ τίμιος

There’s a great blog post about this that lays it all out here.

Many-moneyed Men

I want to linger for a minute on the fragment while thinking about Homer. The words χρήματ' ἀνήρ· πενιχρὸς δὲ οὐδεὶς πέλετ' ἐσλὸς οὐδὲ / τίμιος provide a way for thinking about the elision of character and attributes in the epic’s first book and, by doing so, for reconsidering how the Iliad invites audiences to think about material wealth, identity, and the obligations between individuals and their communities

Let’s start with the first two words, a nominal sentence χρήματ' ἀνήρ. Today, we translate it as “money is the man,” or” man is money” when it could also mean something like “a man is his things–so no one poor is noble nor honored”. As a Homerist, I cannot help but hear these lines and think of Iliad 1 where the value statements of esthlos (“noble, good”) and timios (“honored”) are asserted and reinterpreted during conversations Agamemnon complains that Calchas’ speech is never “good” (esthlon, 1.08) and the gods worry about the feast being disrupted by strife, depriving them of “noble pleasure” (1.576). Achilles accuses Agamemnon of expecting the Achaeans to “gather up honor [timê]” for him and Menelaos (1.159), while Agamemnon points out that others will honor him (timêsousi, 1.175) and Nestor later asserts that the two men are not of the same honor (timês, 1.278) and Achilles asks Thetis to ensure that Zeus will provide honor for him (timên, 1.353) to make up for his lost esteem.

Focusing on just the terms translated here as “noble” and “honor” leaves out an essential metaphorical step in the fragment. The slight to Achilles’ timê is concrete–he, the narrator, and others point to the removal of his prize possession (geras), the captured woman Briseis, as an alteration of his esteem. A way to rephrase the situation in book 1 might be: a man is his things [geras]: and no one poor is noble or honored. So, by depriving Achilles of a thing, Agamemnon has undermined his social standing as well as his esteem.

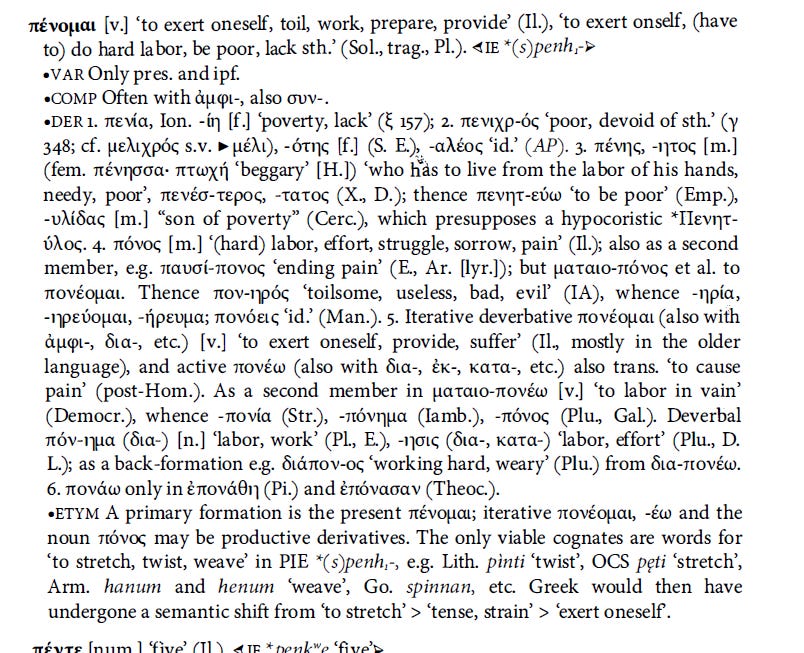

The social standing part probably needs a little more attention. To gloss this with one more step, the word for poor, penikhros, is derived from a verbal root that has to do with toil and work. The semantic range is likely that people who have to labor are not already worth the goods that would qualify them for a specific class and a level of honor. (Or, more generously, if you don’t have wealth, you need to work; there’s also the additional resonance of ponos as suffering to consider.)

But wait, there’s more: it isn’t just that a person is their money, it is a gendered man who is defined by his possessions and in the world of the Iliad, possessions include other people, especially women. It would, then, not be an unfair reading of the Iliad’s view of the Trojan War that, just as Achilles loses honor by being deprived of Briseis, so too Menelaos lost honor when Helen departed.

Origins, Thoughts

So, what happens in Iliad 1 is, to my taste, crystallized in the fragment attributed to Alcaeus. I can phrase what I think is important in this in two ways: first, I posed this as an elision between a metaphorical esteem (timê) and its concrete representation (geras), both of which are additional symbolic indications of a person’s value and class (i.e., whether or not they need to work). The second way to put it is that there is a collapse of signifier and signified and then a subsequent replacement of the thing itself by its symbolic representation.

In these moves, the money/things cease to be a symbol of a person’s value or worth and end up becoming first a representation of the person and then the persons in fact.. The shifting is not insignificant for the plot of the Iliad: one way to read Achilles’ speeches in book 9 is as a probing of that very collapse between esteem (fame, reputation, social position) and the things that are supposed to represent it. His rejection of the gifts promised by the embassy is in part a rejection of the proposition that, regardless of what you do in the world, your worth is defined by the possessions other people permit you to have.

This interpretive thread interests me for two reasons: first, it provides, as I start to indicate above, a slightly different way of reading Achilles’ alienation and the Iliad’s reflection on heroism, politics, and human communities. The second reason resides in the history of ideas, or, perhaps better, a notional genealogy of the values explored in Homer and how they are selected and received in subsequent generations.

I have been inspired by scholars who have recently explored the origins of certain aspects of modern culture in epic. Edith Hall has argued that the Iliad’s extractive and consumptive relationship with the environment foreshadows and informs modernity’s destruction of the environment. Similarly, Jackie Murray and Patrice Rankine have traced modern approaches to race and enslavement back to ancient epic, in its casualization of class violence, proto-racialization with races of heroes and demigods, and the implicit cultural structure that facilitates the domination of one person over another based on gender, class, and race.

When I look at the extreme inequality of late-stage capitalism, its subverting of participatory systems of governance, and the casual violence it perpetuates both domestically and internationally, I can’t help but follow the model of these scholars and look for the history of the values that enable and encourage our current march toward self-destruction. There is a symbolic harmony as well between a system of human value that equates persons with things and downgrades actual human labor and the extractive and exploitative systems of oppression and environmental devastation. One could argue that the Iliad contains the structures and ideas that have led to the rampant inequality and extractive expansion characteristic of modern, state-abetted capitalism.

The Structures of Poems and (mis)Reading

The final sentence of the last paragraph, however, is not the whole story. It would be simplistic to say that epic is the root of modern capitalism. It would be better, but still insufficiently nuanced, to say that epic reflects the roots of our modern world. Instead, I would return to what I have written before that Homeric epic is both a product and producer of culture. It reflects and embeds a system of values in its own narrative, but not without pressing on them, questioning them, and asking audiences to do the same.

In an article in the Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic (2018), I argue that early Greek epic both embeds a thematic pattern in its narratives and is shaped by the basic aesthetics of that pattern. Homer and Hesiod both provide themes of strife (eris, neikos) issuing from conflicts over the division or distribution of goods (dasmos), and requiring a judgment or resolution (krisis) that also expects audiences to make additional determinations through the act of interpretation. The conflict of Hesiod’s Theogony is in part resolved by the stabilization and concretization of divine timai and gerai when Zeus assigns rights and spheres of influence to the gods.

The problem is that stability is not possible for human communities because we are constantly in a process of change. There is death-cult aspect to what is on offer in the Iliad that relates to this problem. Achilles, as he famously articulates it, is offered the choice of a long life in ignominy or a short one with kleos aphthiton. The vegetal aspect of the adjective “imperishable” here is important: this kind of kleos cannot wither and die like the mortal substance it is linked too. The transformation from a moneyed-man who can lose the tokens of esteem that become that esteem itself into an eternal tale strives in part to face the challenge of the continual redistribution of human life. Yet, as I have suggested elsewhere (most recently, Storylife, chapter 4), Achilles doesn’t make that choice and no one in the Iliad seems to support such a vision for kleos, with the exception of figures who have no other option (like Hektor).

The discussion of kleos, however, is something of an aside. What early Greek poetry shows is that the distribution of things creates conflict that leads to the need for human beings to make judgment about the world, both in terms of the division of goods and the meaning of human life relative to that distribution. If we follow the thematic arcs of both epics, they challenge a simplistic approach to wealth–that man is indeed his possessions–but they do not fundamentally question whether or not a human being can and should be a possession contributing to someone else’s honor; or whether it is right to commit violence and end human lives for excess wealth (although the Iliad shows that’s pretty stupid).

Each epic does ask us to think about the tension between how someone is valued in a community for their wealth and power and what they actually do in the world. This doesn’t undercut the notion that a person is what they possess; instead, it acknowledges the structure of a world where many accept that definition and asks audiences to see the fundamental limitations of attaching a person’s worth to the things they own.

A few thins to read

Brown, Adam. “Homeric talents and the ethics of exchange.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 118, 1998, pp. 165-172. Doi: 10.2307/632237

Christensen, Joel P. “Eris and Epos: Composition, Competition and the ‘Domestication’ of Strife.” YAGE 2: 1–39.

De Cristofaro, Luigi. “Reading the raids : the sacred value of the spoils : some considerations on Il., 2, 686-694, Il., 9, 128-140 and Il., 19, 252-266.” Rivista di Cultura Classica e Medioevale, vol. 61, no. 1, 2019, pp. 11-41. Doi: 10.19272/201906501001

Murray, Jackie. 2021 “Race and Sexuality: Racecraft in the Odyssey” in Denise McCoskey, ed., Bloomsbury Cultural History of Race. Volume 1: Antiquity. 137-156

Mark Peacock, Introducing Money. Economics as social theory 33. London; New York: Routledge, 2013. xii, 212. ISBN 9780415539883. $45.00 (pb).

Rankine, Patrice. “Odysseus as Slave: The Ritual of Domination and Social Death in Homeric Society,” in Reading Ancient Slavery, eds. Richard Alston, Edith Hall, and Laura Proffitt. New York: Bristol, 2011: 34-50.

Ready, Jonathan L. (2007). “Toil and Trouble: the acquisition of spoils in the « Iliad ». TAPA, 137(1), 3-43.

Seaford, Richard, Money and the Early Greek Mind: Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy, Cambridge University Press, 2004, 382pp, $28.99 (spbk), ISBN 0521539927.

Wealth/Economy in Homer

Adamo, Sara. “ un posto per Omero ?.” Incidenza dell’Antico, vol. 20, 2022, pp. 221-233.

Brown, Adam. “Homeric talents and the ethics of exchange.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 118, 1998, pp. 165-172. Doi: 10.2307/632237

Christensen, Joel P.. “Eris and Epos: composition, competition, and the domestication of strife.” Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic, vol. 2, 2018, pp. 1-39. Doi: 10.1163/24688487-00201001

Fox, Rachel Sarah. Feasting practices and changes in Greek society from the Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age. BAR. International Series; 2345. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2012.

Haubold, Johannes (2000). Homer's people: epic poetry and social formation. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Pr.

Jones, Donald W.. “The archaeology and economy of Homeric gift exchange.” Opuscula Atheniensia, vol. 24, 1999, pp. 11-24.

Karanika, Andromache. Voices at work: women, performance, and labor in ancient Greece. Baltimore (Md.): Johns Hopkins University Pr., 2014.

Kelly, Adrian. “ Iliad 9.381-4.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 59, no. 3, 2006, pp. 321-333. Doi: 10.1163/156852506778132400

Kolb, Frank. “ a trading center and commercial city ?.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 108, no. 4, 2004, pp. 577-613.

Korfmann, Manfred. “ archaeological evidence for the period of Troia VI/VII.” Classical World, vol. 91, no. 5, 1997-1998, pp. 369-385.

Koutrouba, Konstantina and Apostolopoulos, Konstantinos. “Home economics in the Homeric epics.” Πλάτων, vol. 52, 2001-2002, pp. 191-208.

Lewis, David M.. “The Homeric roots of helotage.” From Homer to Solon : continuity and change in archaic Greece. Eds. Bernhardt, Johannes C. and Canevaro, Mirko. Mnemosyne. Supplements; 454. Leiden ; Boston (Mass.): Brill, 2022. 64-92. Doi: 10.1163/9789004513631_005

Lyons, Deborah J.. “ ideologies of marriage and exchange in ancient Greece.” Classical Antiquity, vol. 22, no. 1, 2003, pp. 93-134. Doi: 10.1525/ca.2003.22.1.93

Murray, Sarah C.. The collapse of the Mycenaean economy: imports, trade, and institutions, 1300-700 BCE. New York: Cambridge University Pr., 2017.

Olsen, Barbara A.. “The worlds of Penelope : women in the Mycenaean and Homeric economies.” Arethusa, vol. 48, no. 2, 2015, pp. 107-138.

Piquero Rodríguez, Juan. “« Blood-money » : la compensación por homicidio en la Grecia micénica.” Δῶρα τά οἱ δίδομεν φιλέοντες : homenaje al profesor Emilio Crespo. Eds. Conti Jiménez, Luz, Fornieles Sánchez, Raquel and Jiménez López, María Dolores. Madrid: Ed. de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 2020. 221-229.

Rose, P. W.. Class in archaic Greece. Cambridge Books Online. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Pr., 2012.

Scodel, Ruth. “Odysseus' dog and the productive household.” Hermes, vol. 133, no. 4, 2005, pp. 401-408.

Seaford, Richard A. S.. Money and the early Greek mind: Homer, philosophy, tragedy. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Pr., 2004.

Tandy, David W.. Warriors into traders: the power of the market in early Greece. Classics and contemporary thought; 5. Berkeley (Calif.): University of California Pr., 1997.

Thomas, Carol G.. “Penelope's worth ; looming large in early Greece.” Hermes, vol. CXVI, 1988, pp. 257-264.

Van Wees, Hans (1992). Status warriors : war, violence and society in Homer and history. Amsterdam: Gieben.