In the first book of the Iliad, Nestor attempts to intervene in the conflict between Achilles and Agamemnon. He eventually tells both men to simmer down—Achilles should act insubordinately and Agamemnon shouldn’t take Briseis. Neither of them listen to him. The reason—beyond the fact that neither of them are in a compromising state of mind—may in part be because of the story Nestor tells.

Il. 1.259–273

“But listen to me: both of you are younger than me; for long before have I accompanied men better than even you and they never disregarded me. For I never have seen those sort of men since, nor do I expect to see them; men like Perithoos and Dryas, the shepherd of the host, and Kaineus and Exadios and godly Polyphemos and Aigeus’ son Theseus, who was equal to the gods; indeed these were the strongest of mortal men who lived—they were the strongest and they fought with the strongest, mountain-inhabiting beasts, and they destroyed them violently. And I accompanied them when I left Pylos far off from a distant land when they summoned me themselves; and I fought on my own. No one could fight with them, none of those mortals who now are on the earth. Even they listened to my counsel and heeded my speech.”

ἀλλὰ πίθεσθ'· ἄμφω δὲ νεωτέρω ἐστὸν ἐμεῖο·

ἤδη γάρ ποτ' ἐγὼ καὶ ἀρείοσιν ἠέ περ ὑμῖν

ἀνδράσιν ὡμίλησα, καὶ οὔ ποτέ μ' οἵ γ' ἀθέριζον.

οὐ γάρ πω τοίους ἴδον ἀνέρας οὐδὲ ἴδωμαι,

οἷον Πειρίθοόν τε Δρύαντά τε ποιμένα λαῶν

Καινέα τ' ᾿Εξάδιόν τε καὶ ἀντίθεον Πολύφημον

Θησέα τ' Αἰγεΐδην, ἐπιείκελον ἀθανάτοισιν·

κάρτιστοι δὴ κεῖνοι ἐπιχθονίων τράφεν ἀνδρῶν·

κάρτιστοι μὲν ἔσαν καὶ καρτίστοις ἐμάχοντο

φηρσὶν ὀρεσκῴοισι καὶ ἐκπάγλως ἀπόλεσσαν.

καὶ μὲν τοῖσιν ἐγὼ μεθομίλεον ἐκ Πύλου ἐλθὼν

τηλόθεν ἐξ ἀπίης γαίης· καλέσαντο γὰρ αὐτοί·

καὶ μαχόμην κατ' ἔμ' αὐτὸν ἐγώ· κείνοισι δ' ἂν οὔ τις

τῶν οἳ νῦν βροτοί εἰσιν ἐπιχθόνιοι μαχέοιτο·

καὶ μέν μευ βουλέων ξύνιεν πείθοντό τε μύθῳ·

Ancient commentators praise Nestor elsewhere for his ability to apply appropriate examples in his persuasive speeches:

Schol. Ad Il. 23.630b ex. 1-6: “[Nestor] always uses appropriate examples. For, whenever he wants to encourage someone to enter one-on-one combat, he speaks of the story of Ereuthaliôn (7.136-56); when he wanted to rouse Achilles to battle, he told the story of the Elean war (11.671¬–761). And here in the games for Patroklos, he reminds them of an ancient funeral contest."

ex. ὡς ὁπότε κρείοντ'<—᾿Επειοί>: ἀεὶ οἰκείοις παραδείγμασι χρῆται· ὅταν μὲν γάρ τινα ἐπὶ μονομάχιον ἐξαναστῆσαι θέλῃ, τὰ περὶ ᾿Ερευθαλίωνα (sc. Η 136—56) λέγει, ὅταν δὲ ᾿Αχιλλέα ἐπὶ τὴν μάχην, τὰ περὶ τὸν ᾿Ηλειακὸν πόλεμον (sc. Λ 671—761)·

καὶ ἐν τοῖς ἐπὶ Πατρόκλῳ ἄθλοις παλαιοῦ ἐπιταφίου μέμνηται ἀγῶνος.

The scholia also assert that such use of stories from the past is typical of and appropriate to elders:

Schol. ad Il. 9.447b ex. 1-2 : “The elderly are storytellers and they persuade with examples from the past. In other cases, the tale assuages the anger..."

μυθολόγοι οἱ γέροντες καὶ παραδείγμασι παραμυθούμενοι. ἄλλως τε ψυχαγωγεῖ τὴν ὀργὴν ὁ μῦθος.

Not just elders of course! Singers and teachers are positioned as authorities who should (and do) use narrative examples to form the characters of the young (the first comment comes in response to Achilles’ playing of the lyre; the second comment is prompted by Phoinix’s tale of Meleager presented to Achilles in the 9th book of the Iliad:

Schol. A ad. Il. 9.189b ex. 1-2: “Klea andrôn: [this is because] it is right to be ever-mindful of good men. For singers make their audiences wise through ancient narratives.”

ex. κλέα ἀνδρῶν: ὅτι ἀειμνήστους δεῖ τοὺς ἀγαθοὺς εἶναι· οἱ γὰρ ἀοιδοὶ διὰ τῶν παλαιῶν ἱστοριῶν τοὺς ἀκούοντας ἐσωφρόνιζον.

Schol. ad Il. 9.447b ex. 1-2 : “The elderly are storytellers and they persuade with examples from the past. In other cases, the tale assuages the anger…”

μυθολόγοι οἱ γέροντες καὶ παραδείγμασι παραμυθούμενοι. ἄλλως τε ψυχαγωγεῖ τὴν ὀργὴν ὁ μῦθος.

For Nestor’s speech, the ancient critics do concede that there is some rhetorical grace in the elder’s choice of detail:

Schol. bT ad Il. 1.271c ex. 3-5: “[Nestor] does not mention that Peleus [Achilles’ father] was Agamemnon’s friend so that he doesn’t appear to be rebuking Achilles if his father obeyed him some, but he does not.”

Πηλέως δὲ οὐκ ἐμνήσθη ὡς ᾿Αγαμέμνονος φίλος, ἵνα μὴ δοκῇ ἐλέγχειν ᾿Αχιλλέα, εἴ γε ὁ πατὴρ αὐτοῦ τι πέπεισται, ὁ δὲ οὔ.

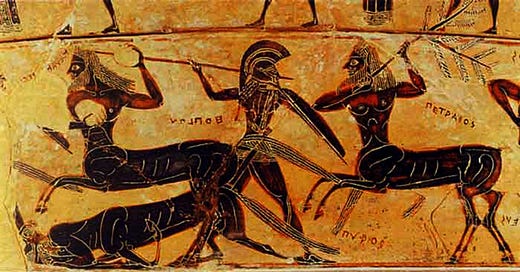

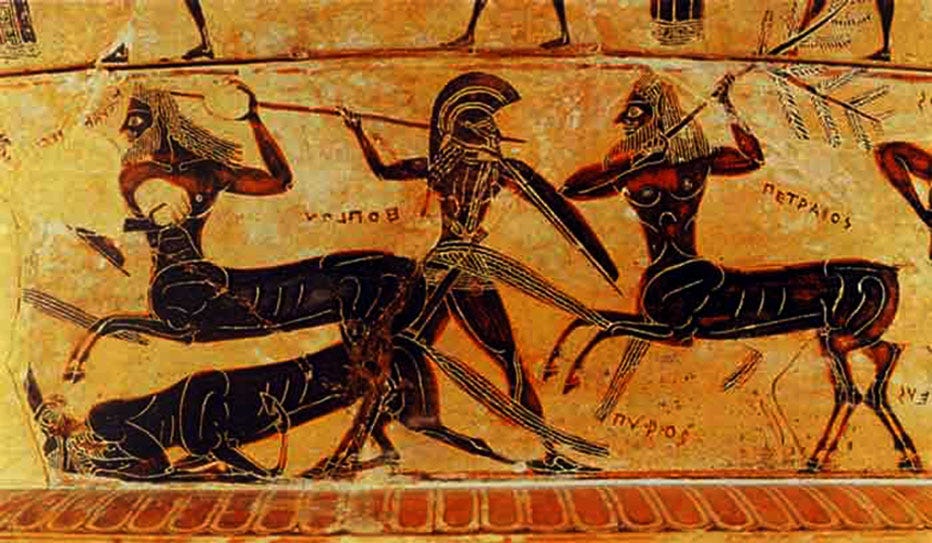

But in explaining the details of Nestor’s speech—that he is alluding to the mythical battle of the Lapiths vs. the Centaurs—the scholiast may hit upon part of the problem of Nestor’s example:

Schol. bT ad Il. 1.266 ex 1-2: “These were the strongest men: but they were the strongest in competing against the remaining beasts”.

<κάρτιστοι δὴ κεῖνοι—ἀπόλεσσαν:> κάρτιστοι μὲν οὗτοι τῶν ἀνδρῶν· ἐκεῖνοι δὲ κράτιστοι πρὸς τὰ λοιπὰ συγκρινόμενοι θηρία.

Unlike Nestor’s other tales, this one does not fit the context. He uses it in an attempt to establish his own heroic bona fides. But what his audience(s) hear is some rambling tale about fighting beasts they are not fighting. The conflict is between men who are supposed to be on the same side.

As an aside, Xenophanes would prefer we avoid talking about Centaurs altogether:

Xenophanes, fr. B1 13-24

“First, it is right for merry men to praise the god

with righteous tales and cleansing words

after they have poured libations and prayed to be able to do

what is right: in fact, these things are easier to do,

instead of sacrilege. It is right as well to drink as much as you can

and still go home without help, unless you are very old.

It is right to praise a man who shares noble ideas when drinking

so that we remember and work towards excellence.

It is not right to narrate the wars of Titans or Giants

nor again of Centaurs, the fantasies of our forebears,

Nor of destructive strife. There is nothing useful in these tales.

It is right always to keep in mind good thoughts of the gods.”χρὴ δὲ πρῶτον μὲν θεὸν ὑμνεῖν εὔφρονας ἄνδρας

εὐφήμοις μύθοις καὶ καθαροῖσι λόγοις,

σπείσαντάς τε καὶ εὐξαμένους τὰ δίκαια δύνασθαι

πρήσσειν• ταῦτα γὰρ ὦν ἐστι προχειρότερον,

οὐχ ὕβρεις• πίνειν δ’ ὁπόσον κεν ἔχων ἀφίκοιο

οἴκαδ’ ἄνευ προπόλου μὴ πάνυ γηραλέος.

ἀνδρῶν δ’ αἰνεῖν τοῦτον ὃς ἐσθλὰ πιὼν ἀναφαίνει,

ὡς ἦι μνημοσύνη καὶ τόνος ἀμφ’ ἀρετῆς,

οὔ τι μάχας διέπειν Τιτήνων οὐδὲ Γιγάντων

οὐδὲ Κενταύρων, πλάσμα τῶν προτέρων,

ἢ στάσιας σφεδανάς• τοῖς οὐδὲν χρηστὸν ἔνεστιν•

θεῶν προμηθείην αἰὲν ἔχειν ἀγαθήν.

Post-Script:

In a later post, I will talk more about what I see as some of the most important themes to emphasize when working with students on the Iliad. One of them is the way Homeric poetry positions itself in relation to other narrative traditions.

A commonly recognized feature in the speeches of Homer’s heroes is the offering of an example from another mythical tradition, called a paradeigma. In particular, paradeigmata provide an opportunity to think about how Homeric characters relate to stories from their own past and make sense of their present. At the same time, they also provide opportunities for audiences to think about how the Iliad might be used as a paradigm for their lives.

My personal take is that the Iliad is particularly interested in where examples from other narratives create dissonance with the contexts to which they are compared. This example from book one in the Iliad is a clear one; but the epic ends with such an example as well when Achilles provides the paradigm of Niobe to Priam in order to convince him to eat. The epic is, in my opinion, engaged from beginning to end in getting audiences to think about just how effective extant narratives are as models for the challenges they face in the world outside the story. And, I think, it anticipates its own use as a problematic model for others, clearly when Achilles says (19.64–65): “This was better for the Hektor and the Trojans: I think that the Achaeans will remember our strife for a long time.” (῞Εκτορι μὲν καὶ Τρωσὶ τὸ κέρδιον· αὐτὰρ ᾿Αχαιοὺς / δηρὸν ἐμῆς καὶ σῆς ἔριδος μνήσεσθαι ὀΐω)

Major Iliadic Paradeigmata

1.259–274 Nestor’s tale of the Lapiths and Centaurs

1.393–407 Thetis’ rescue of Zeus

4.370–400 Agamemnon’s Tale of Tydeus

5.382–404 Dionê’s list of gods harmed by mortals

6.130-140 Diomedes on Lykourgos and Dionysus to Glaukos

7.124–160 Nestor’s one-on-one combat);

9.524–605 Phoinix’s Meleager Tale

11.669–762 Nestor’s story to Patroklos

14.315–328 Zeus’ Erotic Catalogue

15.18–30 Zeus’ Warning to Hera

18.394–405 Thetis’ rescue of Hephaestus;

19. 90–144 Agamemnon’s tale of Atê, Zeus and the birth of Herakles

[23.629–643 Nestor’s Reminiscence]

24.596–620 Achilles’ tale of Niobê

Andersen (1987) on paradeigmata: primary, secondary, and tertiary functions

1. Persuasion of one character by another

2. Reflection of the main story

3. Modeling of reading the epic as a whole; cf. Nagy 2009, 54: “[Homeric] poetry actually demonstrates how myth is activated”

Some things to read on paradeigmata

Andersen, Øivind. 1987. “Myth Paradigm and Spatial Form in the Iliad.” In Homer Beyond Oral Poetry: Recent Trends in Homeric Interpretation, edited by Jan Bermer and Irene J. F. De Jong. John Benjamins.’

Barker, Elton T. E. and Christensen, Joel P. 2011. “On Not Remembering Tydeus: Agamemnon, Diomedes and the Contest for Thebes.” MD: 9–44.

Brenk, F. 1984 “Dear Child: the Speech of Phoinix and the Tragedy of Achilles in the Ninth Book of the Iliad.” Eranos, 86: 77–86.

Braswell, B. K. 1971. “Mythological Innovation in the Iliad.” CQ, 21: 16-26.

Clark, Matthew. 1997. “Chryses’ Supplication: Speech Act and Mythological Allusion.” Classical Antiquity, 17: 5–24.

Combellack, F.M. 1976. “Homer the Innovator.” CP 71: 44-55.

Edmunds, L. 1997. Myth in Homer, in A New Companion to Homer, edited by I. Morris and B. Powell, 415–441. Leiden.

Held, G. 1987. “Phoinix, Agamemnon and Achilles. Problems and Paradeigmata.” CQ 36: 141-54.

Martin, Richard. 1989. The Language of Heroes: Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Ithaca.

Minchin, Elizabeth. 1991. “Speaker and Listener, Text and Context: Some Notes on the Encounter of Nestor and Patroklos in Iliad 11.” CW 84: 273-285.

Nagy, Gregory. 1996. Homeric Questions, Austin.

---,---. 2009. “Homer and Greek Myth.” Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology, 52–82.

Pedrick, V. 1983. “The Paradigmatic Nature of Nestor’s Speech in Iliad 11.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Society, 113:55-68.

Tierney, William G. 1989. Curricular Landscapes, Democratic Vistas: Transformative Leadership in Higher Education New York: Praeger.

Toohey, Peter. 1994. “Epic and Rhetoric.” In Persuasion: Greek Rhetoric in Actions edited by Ian Worthington. London: Routledge: 153–75.

Willcock, M.M. 1967. “Mythological Paradeigmata in the Iliad.” Classical Quarterly, 14:141-151.

____,____. 1977, Ad hoc invention in the Iliad, HSCP 81:41–53.

Yamagata, Naoko. 1991. “Phoinix’s Speech: Is Achilles Punished?” Classical Quarterly, 41:1-15.