Spears and Stones will Break Your Bones But Words Will Always Shape You

Aeneas' Speech to Achilles in Iliad 20

This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 20. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

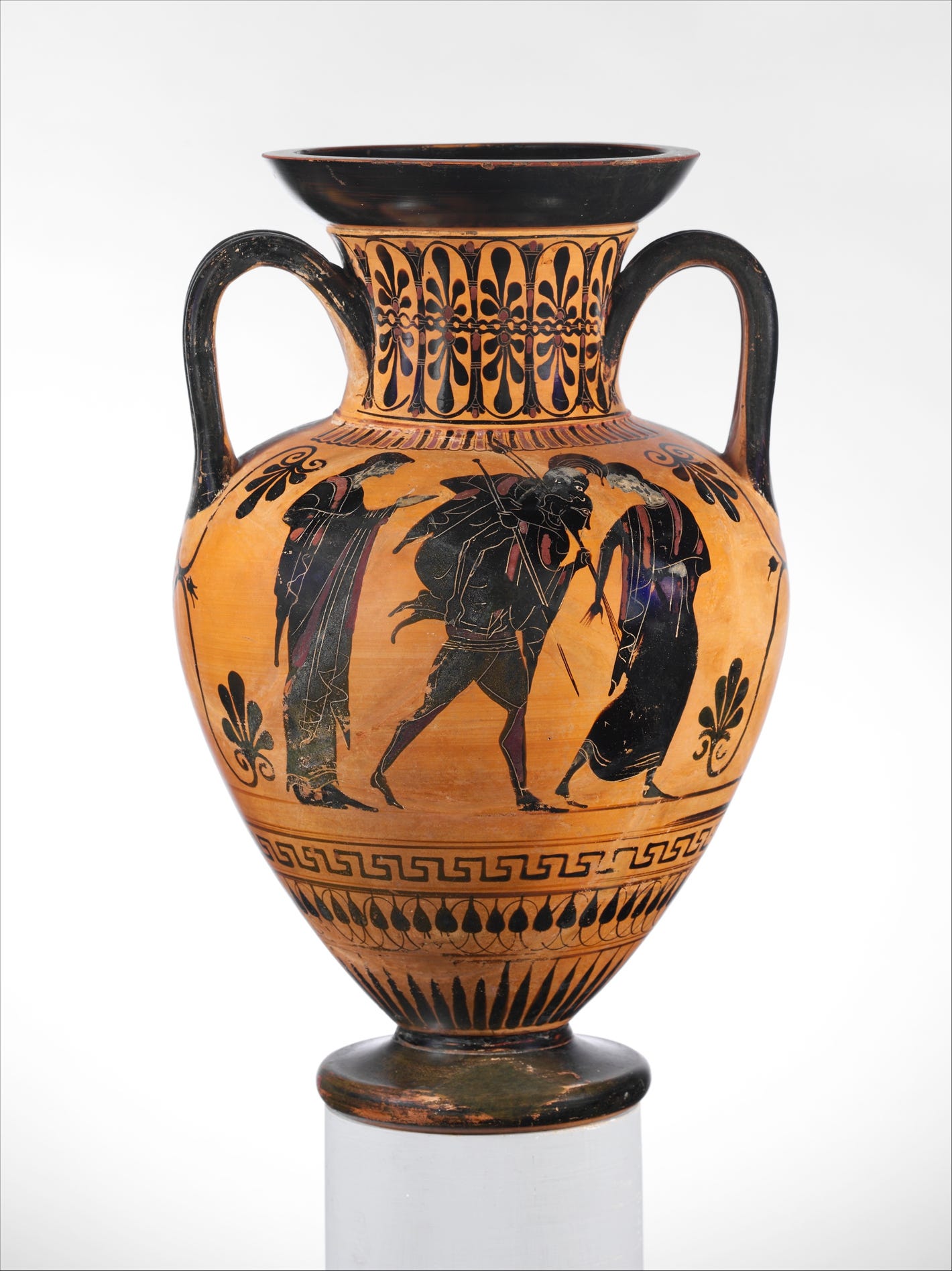

As I mention in the first post on book 20, the larger part of the book is dedicated to the faceoff between Achilles and Aeneas, which is, as the tradition would have it, not their first. The two heroes are well-matched for the clear reason that they both have divine mothers and the less clear reason that they are both subordinate to lesser kings and may be experiencing frustration or displacement thanks to this (see Cramer 2000 and Fenno 2008 on Aeneas’ rage; Nagy 1979 on the episode in general). But this passage also brings into conflict heroes on radically different paths: one of them will die Troy falls; the other will live beyond them, despite his own desires.

It is fair to wonder what this episode brings to the epic. Some have imagined families tracing their lineage back to Aeneas having an undue effect on the formation of the Iliad as we have it. Others have seen thematic ties exploring similar heroes and their place in the universe, as part of epic’s movement towards the mortal world. This encounter certainly primes audiences to think about what kind of man Achilles is in comparison to others and it provides a fine transition to the otherworldly events of Iliad 21 even as it delays the progression of the plot towards Hektor’s death. I suspect it does all of these things while also reflecting on the power of narratives to shape the world and our perspectives on it.

Homer, Iliad 20. 199-258

Aeneas answered him and spoke:

Son of Peleus, Don’t expect to frighten me off with words

Like I am a little child, son of Peleus. I myself know well

How to utter insults and threats.

We know each other’s families; we know each other’s parents,

Listening to the older famous stories [epea] of mortal beings—

But you have never seen my parents with your eyes nor have I seen yours.

People say that you are the offspring of blameless Peleus,

From fine-haired Thetis the sea-nymph, your mother.

But I claim that I am the son of great-hearted Anchises

And my mother is Aphrodite.

Now one set of parents will mourn their dear child

Today. For I don’t think that we will wear out battle

Making some kind of distinction from each other with childish words.

But if you want, learn these things too, so that you may know

my lineage, many men know me indeed.Cloud-gathering Zeus fathered Dardanos first.

He founded Dardanis, since sacred Troy was not yet

Populated by mortal people in the plain,

But they were inhabiting the foothills of many-ridged Ida.

Dardanos fathered a son, king Erikthonios

Who became the richest of mortal men.

He had three thousand horses pastured in his land,

Mares who delighted in their tender foals.

The wind Boreas started to long for some of them as they were grazing

And he took the form of a dark-haired stallion and laid down beside them.

They became pregnant and gave birth to twelve foals.

Whenever these offspring would leap over the fertile land,

They would fly without breaking the fruit of the grain;

But when they went leaping over the wide back of the sea,

They used to run on the tops of the waves of the salty-grey.

Erikhthonios fathered Trôs, the lord of the Trojans.

In turn there were three blameless children born from Tros:

Ilos, Assarakos, and divine Ganymede

Who was the most beautiful of all mortal human beings.

The gods snatched him up to be their wine-bearer

Because of his beauty, so he could stay among the immortals.

Ilos then fathered a blameless son, Laomedon;

Laomedon then fathered Tithonos and Priam and then

Lampos and Klutios and Iketon, offshoot of Ares.

Assarakos fathered Kapus, and he fathered the child Anchises.

Then Anchises fathered me and Priam fathered shining Hektor.

I claim to be of this lineage and bloodline.

Zeus increases and diminishes the excellence of men

However he wishes—for he is mightiest of all.But come, let’s not say these things any longer, like children

Who have stopped in the middle of a violent fight.

It is easy for both to hurl out reproaches,

To very many that a hundred-benched ship couldn’t bear the burden.

The mortal tongue is sharp and has every kind of speech

In full supply: the field of words is expansive this way and that.

Whatever kind of thing you can say, you can hear that kind of thing too.

But why really is it necessary for the two of us to reproach

Each other with insults and slander facing one another

Like women who are enraged over some heart-consuming strife,

Going out into the middle of the street to harangue one another

With true things and not. Anger compels them to say these things too.Don’t try to turn me away from courage with words when I am eager

To face you directly with bronze. Come closer now

Let’s take a taste of one another with our bronze spears.”

Aeneas’ speech exchange needs to be understood in part through the framework of the kind of speech in which he is engaging, in this case neikos or what scholars have called “flyting”. The term flyting is typically used to apply to a stylized form of boasting, threats, and insults that appear in Northern European heroic poetry (e.g. Beowulf). Richard Martin argues in his 1989 The Language of Heroes that the genre of aggressive speech marked by reflexes of the noun neikos (“strife, conflict”) share a performative and competitive domain with Homeric poetry itself. So dynamic speakers like Achilles, Aeneas, and others who use narratives from the past are creative and generative in a way the Homeric narrator is. As Jon Hesk summarizes (2006), Homeric flyting follows basic rules—such as not undermining one’s own martial prowess—but that the best speakers bend and break the rules, as with any dynamic and creative genre. And it may be a part of the flyting genre to dismiss the flyting genre—the first rule of Flyte club is you have to talk about flyte club.

Other exchanges show some ambivalence about the efficacy of words instead of wounds—consider the exchanges between Tlepolemos and Sarpedon in book 5 as another example of heroic sons bragging about divine parents. But battlefield performances may also be an opportunity for warriors to imagine and even create different ‘worlds’: consider how the similar genealogical narratives provided by Diomedes and Glaukos in Iliad 6 allow the heroes not to fight one another.

Hesk argues, further, that Aeneas’ speech in response to Achilles functions in a way as “anti-flyting” (or, at least, an instance of what he calls “meta-flyting”). Then structure of this speech is built around three basic parts, linked with a repeated complaint about speaking like children, and then expanded into a dismissal of what they are doing by comparing them to women in the street. In these moves, Aeneas casts their shared actions as un-heroic, comparing them to children and women the way Diomedes denigrates Paris when he shoots him in the foot in book 11. Yet, as in that example, the truth of the matter is that the words don’t change the reality: Paris may not have killed Diomedes, but for all the latter’s bluster, he still needs to retreat from battle.

Aeneas creates a ring structure in his speech that minimizes the language with which he is engaging even as he uses the form to an immediate effect: he calls boastful speech childish twice, then provides a lengthy genealogy that emphasizes his paternal line, not the line of his divine mother, and then closes by questioning the genre again. His genealogy is, as Hesk observes, the most extensive in the Iliad. After delivering it, Aeneas calls the form of the speech childish for a third time, but expands on what he means: he says it is easy to hurl out reproaches and people can say anything they want to say at all. He then shifts to comparing them to women in the street, insulting each other with “true things and not” conceding that they are driven by anger, whatever they say. I have long been intrigued by this speech: I suspect that Aeneas’ emphasis on his paternal genealogy may be aimed at indicating the greater nobility of his family over Achilles’ and his close connection with the city of Troy. As Jon Hesk suggests, Aeneas is responding in part to Achilles’ earlier taunt that he is not Priam’s son.

At the same time, Aeneas’ gesture to the multiplicity of stories available and the willingness of people to say anything, true or false, combined with his emphasis on his mortal genealogy, may downplay both his and Achilles’ divine parentage. After he acknowledges that that people claim are both children of goddesses, Aeneas’ narrative becomes one he presents as genealogical fact, while Achilles’ background is relegated to other peoples’ stories. Ultimately, Aeneas plays the delicate game of criticizing a speech genre even while fully engaging in it. And his speech is memorable and forceful, all the more appropriately since Apollo advised him to meet Achilles in the first place. And, ultimately, as other readers have noted, Achilles’ taunts are proved false by the narrative: Aeneas does not die.

Hesk concludes that Aeneas’ speech “is geared toward the subtle undermining of Achilles as a specific individual in relation to what we know about his character and verbal traits from the rest of the poem” (2006). He builds on some work by Gregory Nagy who has argues that the Iliad admits a different epic tradition into its narrative where Aeneas was a central character (1979, 265-275). When Achilles and Aeneas face each other in battle, there can be no definitive outcome because they are bound by the ‘rules’ of the narrative tradition: Achilles cannot die by Aeneas’ hands and Aeneas must survive to lead the Trojan survivors after the fall of the city. And, yet, the desire to have them meet at all is the fulfillment of the desire for something like a ‘crossover’ episode. This is Superman vs. Batman. No one reasonable believes that the latter could actually defeat the former except under very specific circumstance; and everyone knows that at some point, both of them need to be returned to their own stories.

Again, according to Nagy, a central feature of Aeneas as a character pay have been his ability to craft blame and praise in speech, reflected in his name Aineias, which Nagy links to the word ainos (for praise). In telling a different story about the world, one that makes it focused on mortal genealogy, I suspect that Aeneas may be writing Achilles out of history and imagining a post-heroic world for himself where being a child of a goddess is less important than carrying on a family story.

Much of this makes me reconsider another ‘meta-flyting’ moment in the Iliad and that is when Hektor pauses before facing Achilles and admits he wishes he and Achilles could just talk to each other like young lovers. We may imagine Hektor ruminating over the limits of flyting and the martial performance of speech. His genealogy and story-telling is of little use in the conflict he is about to face. Yet, if they were allowed to speak under different rules, the outcome might be different.

A Short Bibliography for Iliad 20

Andrews, P. B. S.. “The falls of Troy in Greek tradition.” Greece and Rome, vol. XII, 1965, pp. 28-37. Doi: 10.1017/S0017383500014753

Ballesteros, Bernardo. “On « Gilgamesh » and Homer: Ishtar, Aphrodite and the meaning of a parallel.” Classical Quarterly, N. S., vol. 71, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1-21. Doi: 10.1017/S0009838821000513

Beck, Bill. “Harshing Zeus’ μέλω: reassessing the sympathy of Zeus at Iliad 20.21.” American Journal of Philology, vol. 143, no. 3, 2022, pp. 359-384. Doi: 10.1353/ajp.2022.0015

Cramer, David. “The wrath of Aeneas: Iliad 13.455-67 and 20.75-352.” Syllecta classica, vol. 11, 2000, pp. 16-33.

Fenno, Jonathan Brian. “The wrath and vengeance of swift-footed Aeneas in Iliad 13.” Phoenix, vol. 62, no. 1-2, 2008, pp. 145-161.

Hesk, Jon. “Homeric flyting and how to read it: performance and intratext in Iliad 20.83-109 and 20.178-258.” Ramus, vol. 35, no. 1, 2006, pp. 4-28.

Konstan, David. “Homer answers his critics.” Electryone, vol. 3, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1-11.

D. Lohmann, Die Komposition der Reden in der Ilias (Berlin 1970).

Martin, Richard P.. The language of heroes : speech and performance in the Iliad. Myth & poetics. Ithaca (N. Y.): Cornell University Pr., 1989.

Pucci, Pietro. “Theology and poetics in the « Iliad ».” Arethusa, vol. 35, no. 1, 2002, pp. 17-34.

Reece, Steve Taylor. “σῶκος ἐριούνιος Ἑρμῆς (Iliad 20. 72): the modification of a traditional formula.” Glotta, vol. 75, no. 1-2, 1999, pp. 85-106.

Smit, Daan W.. “Achilles, Aeneas and the Hittites : a Hittite model for Iliad XX, 191-194 ?.” Talanta , vol. XX-XXI, 1988-1989, pp. 53-64.

P. M. Smith, ‘Aineiadai as patrons of Iliad XX and the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite’, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, LXXXV. (1981) 17-58.

Wakimoto, Yuka. “Aeneas in and before the « Iliad ».” Journal of Classical Studies, vol. 45, 1997, pp. 28-39.