As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

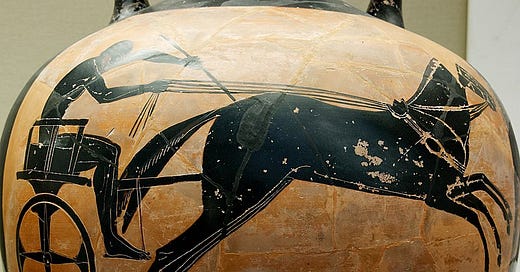

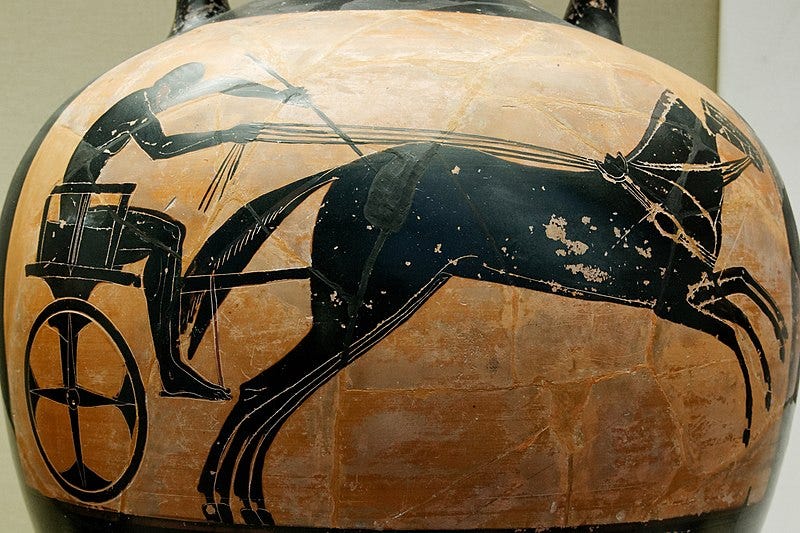

As I discussed in the general post on book 8, this book is bookended by speeches from Zeus. Book 8 invites some conclusion because its structure seems rather dissolute or unsure: between Zeus’ speeches is a confusing battle scene that starts with Nestor wrecking his chariot and Diomedes rescuing him, near the end of the book, Hektor reigns supreme and nearly kills Nestor and Diomedes. On either side of this action, Hera and Athena flirt with intervening before Zeus’ stops them and rearticulates the plot.

In important ways, these scenes prepare us for the crisis that motivates the return to Achilles in book 9; but they also act somewhat retrospectively, reinforcing the the themes of the epic’s first third, including Zeus’ control over the action, his managing of the other gods’ defense, and the raising up of other Achaeans, like Diomedes and Nestor, in the face of a vacuum of leadership. Such recapitulations and thematic ‘turning’, I suggest, supports the idea that book 8 is something of a potential stopping point in performance. Even if such thematic reinforcement does not exclusively serve the halting of a performance, at the very least it refocuses the plot on the “plan of Zeus”, the suffering of the Achaeans, and the absence of Achilles.

Such arguments for narrative coherence, however, have often met resistance in Homeric scholarship. In his article “On the “Importance of Iliad book 8”, Erwin cook addresses the scene where Diomedes rescues Nestor from his wrecked chariot. As he notes, many have argued that the scene is modeled on something allegedly included in the lost poem the Aithiopis and that, since the Aithiopis was ‘later’ than the Iliad, that this scene is not a proper part of book 8 and is therefore some sort of a later addition (an interpolation). Cook shows how this book reminds audiences of Zeus’ plan for Achilles and activates the theme of grief (Homeric akhos) repeatedly in its service. He concludes “Homer has marshaled the considerable resources at his disposal, including his inherited traditions and narrative art, with the twin objectives of inspiring akhos in his audience and thereby heightening the emotional drama of the pivotal scene that leads to the embassy to Akhilleus in the next book.”

The late Martin West, probably one of the most famous and successful Hellenists in the Anglophone world over the past two or generations, became a strong proponent of neoanalysis in the latter part of his career. This approach takes its final form in the two Making of.. Books publishing by Oxford (Making of the Iliad and The Making of the Odyssey), which set out to isolate the ‘original’ version of each poem as it was composed (even written) by individual poets, before the texts were ruined by editors and later scholars. (Not to mention time…). While West’s brilliance as an editor and commentator (his editions of Hesiod have not been surpassed in 60 years) certainly gained these arguments an immediate audience, their reception was not universally positive. In a review of his Iliad book, Bruce Heiden starts by quipping “Despite its misleading title, The Making of the Iliad is not about the Iliad. Its subject matter is an unattested, completely imaginary archaic Greek hexameter poem whose development as a work-in-progress M. L. West sketches in some detail.”

West’s approach is likely the most extreme version of a resuscitation of the analytical approach to Homer. This approach was dominant in the 19th century as scholars struggled with inconsistencies in epic language and plot and the vicissitudes of textual transmission. The scholarship of this school was so rigorous and convincing that by the 1920s, the opposing “Unitarians” were largely discredited as romantics and fools. Of course, the rise of oral-formulaic theory with the work of Milman Parry and Albert Lord changed this story by providing a different way to think about the art of Homeric language and composition. But West would not be the only scholar and reader frustrated by the next half-century of work endeavoring to explore or “prove” Homeric orality.

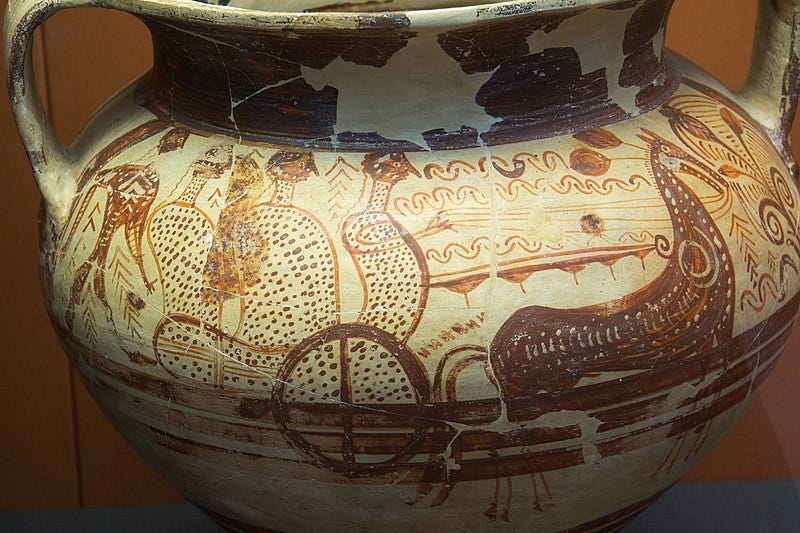

At one significant level, the return to neoanalysis provides permission to think about the way the Homeric epics we have were influenced by other story traditions (in part, the topic of my book with Elton Barker, Homer’s Thebes). As is clear from Cook’s discussion of the chariot scene in Iliad 8, the Iliad is replete with scenes that echo, draw on, or otherwise engage with what we think we know from other narrative traditions. There are, however, significant challenges to this approach: First, there’s a circularity in what we know about these traditions because they are by and large preserved as part of the commentary tradition on the Iliad and the Odyssey (by which I mean the majority of what we know about poems from the epic cycle and other epic traditions remain only in connection with the Homeric epics).

Second, there is a danger to the assumption that a shared narrative pattern necessarily shows direct connection. As Elton and I argue in our first article together (“Flight Club….”), a shared element could be evidence of influence in either direction, of both traditions drawing on a common antecedent, or, as is more likely, of something much more complicated. In an oral performance tradition, different versions of stories play off one another, creating similarity and difference in a cycle whose end products are nearly impossible to disentangle. Neoanalysis–like analysis before it, can yield a simplistic judgment on relationships between texts: “The level of specificity and correspondence assumed by neoanalytical studies relies on levels of fixity and repetition characteristic of literary texts and not oral traditions.” (As we put it in Homer’s Thebes see Marks 2008:9–11 criticizes neoanalysis for a diachronic approach that betrays a “source and recipient model” (10))

Now, this is not to claim by any means that neoanalysis has little to offer. A sophisticated approach to the relationship between poetic traditions can demonstrate quite effectively how shared diction, motifs, and narrative patterns are used to create different narrative traditions. There is, I think, ample space for a performance based kind of analytical reading of ancient myth and poetry. And I think some scholars like Bruno Currie or Thomas Nelson are nearing that (even if the reliance on allusion gives me the screaming fantods). One of the things that is interesting about neoanalysis is a tendency to try to “establish the priority of the non-Homeric material” ( Kelly 2012:227).

In general, I have no qualms with showing Homeric poetry stands at the end of a tradition rather than the beginning (because, well, I think it works that way). My wariness comes more from the positivistic approach that identifies Homer with something we don’t have, except in scholarship on Homer and in prizing a one-to-one correspondence between a passage in Homer and another text without considering the steps in between, the various versions of either tradition that may have existed, or other lost narratives that shaped the Homeric ones we are trying to contextualize.

But the primary qualm I have developed with neoanalysis and similar approaches over the years is that it is too firmly situated in the business of authorship and too little concerned with the experiences of audiences. This is, to a great extent, my discomfort with the language of allusion as well: in its worst examples, the identification of allusion functions to illustrate the cleverness and knowledge of the critic beyond the realistic operations of the narrative. Neoanalysis and similar approaches do too little to show to what extent audiences were aware of similarities between performed texts. They engage in what I playfully deride as “supply side poetics”, imagining that the full weight of the meaning of poetry comes from what the author wanted it to mean and not from what audiences are willing and able to entertain.

In Homer’s Thebes Elton and I have a home-made graphic illustrating the way meaning making is modeled here: it leaves too little room for audience engagement, misinterpretation, and the mechanics of reception. In addition, it is too insensitive to the potential for multiple versions of ‘traditional’ narratives building off one another, cannibalizing themselves, and competing for attention in an iterative process.

When it comes to Iliad 8, the structure seems to so well articulate prior themes and set the audience up for the return to the political themes of book 9. Note as well that Diomedes and Nestor are crucial to the beginning of that book, too, creating a bridge between the human action of books 8 and 9. Zeus and Hektor are similarly absent from the later book, despite the clear influence they still wield over its action. It is interesting to consider how these plots may have been similar to other stories, but I think one can see that audiences can enjoy the Iliad without any knowledge of this controversy at all.

Almost as if Homeric epic transcends the need for any other stories at all….

Short bibliography on Neoanalysis

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Burgess, Jonathan. “Beyond Neo-Analysis: Problems with the Vengeance Theory.” The American Journal of Philology 118, no. 1 (1997): 1–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1562096.

Cook, Erwin F. “On the ‘Importance’ of Iliad Book 8.” Classical Philology 104, no. 2 (2009): 133–61.

Currie, B. 2016. Homer’s Allusive Art. Oxford.

Danek, G. 1998. Epos und Zitat: Studien zur Quellen der Odyssee. Vienna.

Kakridis, J. T. 1949. Homeric Researches. Lund.

Kelly, A. 2006. “Neoanalysis and the Nestorbedrängnis: A Test Case.” Hermes 134: 1–25.

Kelly, Adrian. 2007. A Referential Commentary and Lexicon to Homer, “Iliad” VIII. Oxford.

Kelly, Adrian. 2012. “The Mourning of Thetis: ‘Allusion’ and the Future in the Iliad.” In F. Montanari, A. Rengakos, and C. Tsagalis, 211–256. Leiden.

Kullmann, W. 1960. Die Quellen der Ilias. Wiesbaden.

———. 1984. “Oral Poetry Theory and Neoanalysis in Homeric Research.” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 25:307–324.

Kullmann, Wolfgang. “Gods and Men in the Iliad and the Odyssey.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 89 (1985): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/311265.

———. 2002. “Nachlese zur Neoanalyse.” In Realität, Imagination und Theorie, ed. A. Rengakos, 162–176. Stuttgart.

Marks, J. R. 2008. Zeus in the Odyssey. Hellenic Studies 31. Washington, DC.

Nelson, Thomas J. 2023. Markers of Allusion in Archaic Greek Poetry. Cambridge (Cambridge University Press).

READY, JONATHAN L. Review of NEOANALYSIS AND HOMER, by F. Montanari, A. Rengakos, and C. Tsagalis. The Classical Review 63, no. 2 (2013): 321–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43301410.

WEST, MARTIN. “The Homeric Question Today.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 155, no. 4 (2011): 383–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23208780.

Willcock, M. M. . 1997. “Neo-Analysis.” In Morris and Powell 1997:174–189.