This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 20. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Schol. T Ad Hom. Il. 20.307-8

“Some people say that [the children of Aeneas live on] through the Romans, which the poet knew from the oracles of the Sibyl, while others claim that the Aiolians expelled the descendants of Aeneas. But those who claim that Aphrodite devised the Trojan War because she knew this are wrong”

οἱ μὲν διὰ ῾Ρωμαίους φασίν, ἅπερ εἰδέναι τὸν ποιητὴν ἐκ τῶν Σιβύλλης χρησμῶν, οἱ δέ, ὅτι Αἰολεῖς ἐξέβαλον τοὺς ἀπογόνους Αἰνείου. πταίουσι δέ, ὅσοι φασὶ τοῦτο εἰδυῖαν ᾿Αφροδίτην μηχανήσασθαι τὸν Τρωϊκὸν πόλεμον.

The greater portion of book 20 is dedicated to the faceoff between Achilles and Aeneas, one I have described earlier as a kind of heroic Superman vs. Batman. (And, yes, I think this Aeneas is more Ben Affleck Batman than a Michael Keaton....). Books 20 and 21 together work to delay the inevitable meeting of Hektor and Achilles, but they also provide something of a deliberate tour through different kinds of heroism. In book 21, Achilles challenges divine beings and wrestles a river, turning into his most Heraklean self. In book 20, he faces Aeneas, a hero of a different shape altogether.

As I discuss in the earlier post, Aeneas and Achilles engage in heroic flyting that is more or less an elaborate ‘meta-flyting’. Metapoetic moments in literature invite audiences to think about the rhetorical content of the forms that are entertaining them, both in a critical way and in one that invites enjoyment from those who recognize play and engagement with other traditions. Meta-moments, when they are successful, work on different levels, responding to audience capacity to catch references to other narratives or to understand comparisons in motif, trope, and genre.

When Achilles and Aeneas meet, the audience is invited to a series of meta-motifs: the heroic boast, followed by shifts in type scenes, and hints that there is a world larger than the already very large one contained within the Iliad. For the Iliad, such moments allow it to appropriate from other traditions without becoming them, by subordinating them to its own story. (The Odyssey does this constantly too!) But the act of appropriation itself is adaptive and integrative: it always carries within it the potential for recursive doubling of meaning, for multiple, even contradictory ideological frames to coexist, in tension, producing meaning only when the audience resolves the tension by leaning toward one or the other.

When Achilles and Aeneas meet, there is a problem: Achilles is on a murderous rampage and gets to kill everyone he wants. Aeneas is the son of a goddess who is supposed to live. What in the world is the epic to do?!

Homer, Iliad 20.288-308

Then Aeneas would have struck [Achilles] as he rushed at him

With a stone in the helmet or shield, which would have projected him from ruin,

But Peleus’s son would have robbed him of his life with his sword near at hand—

If Poseidon the earth-shaker had not sharply noticed it all.

Immediately, he spoke this speak among the immortal gods:

“Shit! Truly, I have grief for great-hearted Aeneas

Who soon will go to Hades overcome by Peleus’ son,

All because he listened to the words of far-shooting Apollo,

The fool, that god will not be of any use against harsh ruin.

But why should this guy who isn’t at fault suffer grief now

Without any reason because of other people’s pain when he always

Gave cherished gifts to the gods who hold the wide sky.

But come on, let’s lead him away from death

So that Kronos’ son won’t get enraged somehow if Achilles

Kills him. It is his fate to escape

So that the race of Dardanos won’t go seedless and erased,

Dardanos whom the son of Kronos loved beyond all his children

Who were born to him from mortal women.

Kronos’ son has already turned against Priam’s offspring.

Now, mighty Aeneas will be lord over the Trojans

Along with the children of his children who will be born later on.”ἔνθά κεν Αἰνείας μὲν ἐπεσσύμενον βάλε πέτρῳ

ἢ κόρυθ’ ἠὲ σάκος, τό οἱ ἤρκεσε λυγρὸν ὄλεθρον,

τὸν δέ κε Πηλεΐδης σχεδὸν ἄορι θυμὸν ἀπηύρα,

εἰ μὴ ἄρ’ ὀξὺ νόησε Ποσειδάων ἐνοσίχθων·

αὐτίκα δ’ ἀθανάτοισι θεοῖς μετὰ μῦθον ἔειπεν·

ὢ πόποι ἦ μοι ἄχος μεγαλήτορος Αἰνείαο,

ὃς τάχα Πηλεΐωνι δαμεὶς ῎Αϊδος δὲ κάτεισι

πειθόμενος μύθοισιν ᾿Απόλλωνος ἑκάτοιο

νήπιος, οὐδέ τί οἱ χραισμήσει λυγρὸν ὄλεθρον.

ἀλλὰ τί ἢ νῦν οὗτος ἀναίτιος ἄλγεα πάσχει

μὰψ ἕνεκ’ ἀλλοτρίων ἀχέων, κεχαρισμένα δ’ αἰεὶ

δῶρα θεοῖσι δίδωσι τοὶ οὐρανὸν εὐρὺν ἔχουσιν;

ἀλλ’ ἄγεθ’ ἡμεῖς πέρ μιν ὑπὲκ θανάτου ἀγάγωμεν,

μή πως καὶ Κρονίδης κεχολώσεται, αἴ κεν ᾿Αχιλλεὺς

τόνδε κατακτείνῃ· μόριμον δέ οἵ ἐστ’ ἀλέασθαι,

ὄφρα μὴ ἄσπερμος γενεὴ καὶ ἄφαντος ὄληται

Δαρδάνου, ὃν Κρονίδης περὶ πάντων φίλατο παίδων

οἳ ἕθεν ἐξεγένοντο γυναικῶν τε θνητάων.

ἤδη γὰρ Πριάμου γενεὴν ἔχθηρε Κρονίων·

νῦν δὲ δὴ Αἰνείαο βίη Τρώεσσιν ἀνάξει

καὶ παίδων παῖδες, τοί κεν μετόπισθε γένωνται.

This passage is interesting because of the way it plays upon so many different Homeric motifs. To start, the battle scene is upended: an outcome of the fight is predicted but then denied, twice, as each hero’s next moves are anticipated, but denied. The denial proceeds through a somewhat regular motif in Homeric epic that goes by various names such as “if not-situations” (de Jong 2004, 68-71), “reversal passages” (Morrison 1992) and “pivotal contrafactuals” (Louden 1993, 181). Mabel Lang was one of the first to focus on these ‘unreal conditionals’ that provide the Homeric narrator and characters alike to express what would (or could) have happened, had events turned out different. Like English, Greek grammar marks unreal conditionals—in this case, contrary to fact—with clear signs, such as the use of specific particles in conjunction with particular verb forms (in this case, the aorist indicative in each clause with the Greek modal particle (a short word indicating that the situation is unreal) κε and introductory “if then not/unless” (εἰ μὴ).

It is one thing to describe the grammatical and semantic nature of a construction like this, however, and a wholly different thing to outline the use of a construction in a particular narrative. Unreal conditinoals in Homer seem in particular to create a space wherein Homeric epic flirts with deviating from the external constraints. Morrison, for example, argues that these scenes constitute moments where the traditional story or plot is nearly upended as Homer challenges and distinguishes himself from the tradition.

Morrison divides “reversal passages” into three types: (a) violations of the sack of Troy motif; (b) violations of the Iliad’s plot; and (c) minor variations during battle and in the funeral games (61). Lorenzo Garcia agrees that “in such instances Homer appears to challenge the very tradition in which he is working—which we may think of as a kind of “destiny” for the narrative in its own right...and asserts his own authority for the direction the narrative takes. Such events, As Gregory Nagy puts it, would be “untraditional”. Bruce Louden, however, suggests that commentators have overemphasized the tendency for this device to raise violations of the tradition. Across the 33 instances of this construction in the Iliad, 15 are “corrected” by divine intervention; 15 are addressed by mortals.

I think an undervalued aspect of the construction is its ability to draw attention to an event as contrary to patterns and expectations. It indicates a breaking of suspense and invites audiences to view this event as a course correction. In this way, a small measure of chaos is admitted into an ordered text, acknowledging the instability of narrative even as exerting control over it. This is an appropriate structure, then, for pointing to the potentially tradition-rattling encounter of Achilles and Aeneas.

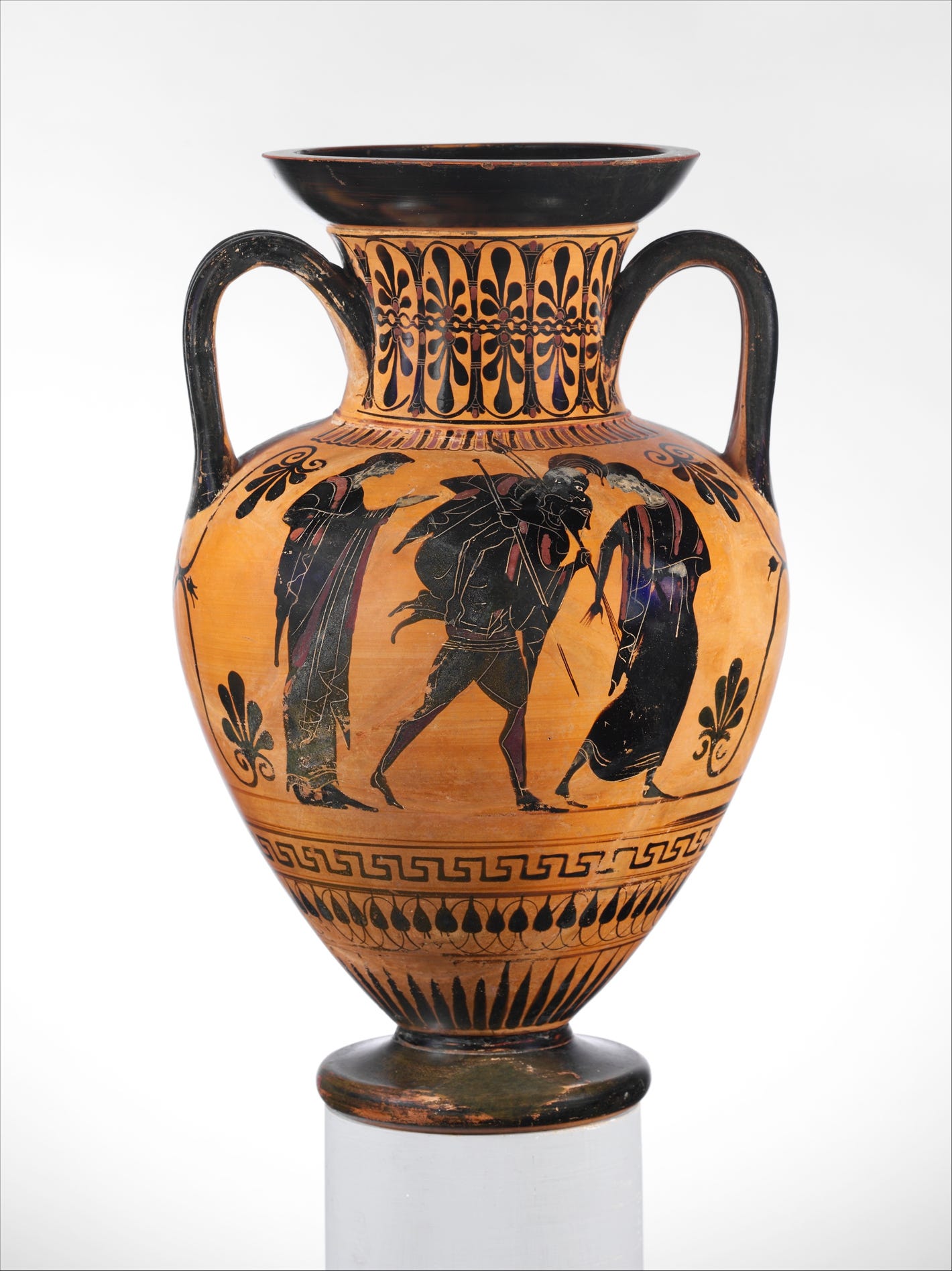

Such tension intrigues me with this case in particular because we have pretty good evidence for extra-Iliadic traditions of Aeneas surviving the fall of Troy from archaeological and iconographic evidence. There are black figure vases from the sixth century BCE that depict Aeneas carrying his father Anchises from Troy. The Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, which centers Anchises, appears to be one of the ‘older’ hymnic tradition; yet in this speech, Poseidon focuses on the future and omits such a reference to the past. The iconography and this speech both point to Aeneas’ survival as a basic fact of the narrative universe, but other than that there is no good reason to imagine these passages as in any way responding to each other, unless we imagine the Homeric epic as leaning away from such a common image, doing the very Homeric thing of making its own space and meaning in between the immutable lines of the larger tradition. As I usually emphasize, there’s no good reason to insist that the images and text are engaging directly with each other or existing in some sort of a temporal—therefore interpretive—hierarchy rather than to understand them as both variations on a shared narrative theme. Instead, it is interesting to go through the process in multiple directions, leaving space as well for the stories we have lost in between.

Divine interest in supporting fate—if we can call it that rather than the narrative instrumentalization of divinity to allow the story to both diverge and converge with what is known—leads me to some final observations on this speech. The presence and the absence of the gods are both felt keenly here. For example, a scholiast asks why Aphrodite isn’t the one to save him and answers it is because she is afraid of Athena ( ἡ ᾿Αφροδίτη τὸν υἱὸν οὐ σῴζει; δέδιεν ᾿Αθηνᾶν, Schol. T ad Il. 20.291a1). When Poseidon worries about the impact of Apollo’s words on Aeneas, I wonder if we can imagine a general anxiety about how the ‘words of Apollo (prophecy and poetry especially) may lead people to ruin.

There may also be wordplay as well around the name Achilles or at least the importance of ‘grief’ for the plot. Poseidon notes that akhos (“grief, woe”), a word often associated with etymologies of Achilles (e.g akhos + laos, “woe for the people”) comes over him when he hears about Aeneas and that Aeneas is suffering because of “other peoples akhos”. I may be so bold as to suggest that Poseidon feels the very same reaction that audiences might be feeling at this moment but also in response to the events of the Iliad. At the same time, he is extending the impact of the same emotion on ‘players’ in the epic itself: akhos drives the plot of the Trojan War, but it also reshapes the plot of the Iliad even as it flirts with diverging from that larger narrative structure.

But we are not yet done with emotional responses to these. In discussing the earlier passage in book 20 where Zeus claims that he is going to sit apart taking pleasure in watching the unfolding events, I suggested that king of gods and men derived this feeling from the sense that the narrative was moving toward a particular end, to a closure he had anticipated, if not arranged. Here, Poseidon notes Zeus’ potential displeasure at a particular outcome’s failure: Zeus will “be angry”( κεχολώσεται) if Achilles should kill Aeneas. Kholos, as I discuss in other posts, drawing on Thomas Walsh’s work, is anger that is socially motivated, among peers. It is an operative word in the conflict between Achilles and Agamemnon in book 1, strife among the gods in books 13-15, and during the funeral games in book 23. (It contrasts, in a complementary way, with menis, which tends to signal rage at cosmic disorder, as Lenny Muellner argues). Indeed, to connect this back to the introductory form, the “pivotal contrafactual”, Tyler Flatt has argued that this structure appears in moments where we may be expected to consider the overlap between the need to mourn and the need to hear further narrative. Poseidon’s concern for Zeus’ emotions foreground the affective nature of narratives that go where we don’t want them to go.

It is almost as if Zeus is presented as both audience and author of the narrative unfolding and, while we could imagine him as indicating the swings of the poem’s external audience, we could also frame this theologically. Zeus is something like an especially keen game master (or DM, dungeon master for the older crowd). He knows where he wants the story to go: he takes pleasure in the players finding their way there, and gets angry when they try to change his plans.

A Short bibliography

BECK, DEBORAH. “EMOTIONAL AND THEMATIC MEANINGS IN A REPEATING HOMERIC MOTIF: A CASE STUDY.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 138 (2018): 150–72. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26575923.

Bouxsein, Hilary. “That Would Have Been Better: Counterfactual Conditions in Homeric Character Speech.” Mnemosyne 73, no. 3 (2020): 353–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26989141.

De Jong, Irene J. F. Narrators and Focalizers: The Presentation of the Story in the Iliad. 2nd Edition. London: Bristol, 2004.

Tyler Flatt. “Narrative Desire and the Limits of Lament in Homer.” The Classical Journal 112, no. 4 (2017): 385–404. https://doi.org/10.5184/classicalj.112.4.0385[JC1] .

Garcia, Lorenzo F., Jr. 2013. Homeric Durability: Telling Time in the Iliad. Hellenic Studies Series 58. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Lang, Mabel L.. “Unreal conditions in Homeric narrative.” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, vol. XXX, 1989, pp. 5-26.

Bruce Louden. “Pivotal Contrafactuals in Homeric Epic.” Classical Antiquity 12 (1993) 181-98.

James V. Morrison. Homeric Misdirection: False Predictions in the Iliad. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1992.

—,—. “Alternatives to the Epic Tradition: Homer’s Challenges in the Iliad.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 122 (1992) 61-71.

Muellner, Leonard. 1996. The Anger of Achilles: Mênis in Greek Epic. Cornell.

Nagy, Gregory. The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. Revised ed. Baltimore. Orig. pub. 1979. 1999

SAUSSY, HAUN. “WRITING IN THE ‘ODYSSEY’: EURYKLEIA, PARRY, JOUSSE, AND THE OPENING OF A LETTER FROM HOMER.” Arethusa 29, no. 3 (1996): 299–338. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26309735.

Walsh, Thomas. Feuding Words, Fighting Words: Anger in the Homeric Poems. Washington, D. C.: Center for Hellenic Studies. 2005

> Across the 33 instances of this construction in the Iliad, 15 are “corrected” by divine intervention; 15 are addressed by mortals.

What happens in the remaining cases?