This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 9. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. This post is a partial excerpt/adaptation from a book called Storylife: On Epic, Narrative, and Living Things, coming out from Yale in late 2024

One debate that attends Iliad 9, but which speaks more to issues of Homeric composition than the interpretation of book 9 as we have it, are the forms of the words that describe the movement of the heralds and the embassy from the Achaean camp in general to Achilles’ dwellings. The passage where this occurs shows what appears to be an inconsistent use of word forms, mixing dual and plural forms in a way that makes it unclear to whom is being referred.

This debate can be somewhat incoherent without knowing a little bit about Ancient Greek language. Early Greek at some point in its history had a full system of nominal and verbal endings for what we call the dual number. To add to the number distinction between singular (I/ you, alone / she, he, it) and plural (We / you all / they), both Greek and Sanskrit have a dual form to describe pairs of things acting together: eyes, twins, people, etc. And these dual forms exist for the different ‘persons’: 1st person: we (two); 2nd person: the two of you, you (two); 3rd person: the two (people, things, etc). In most cases the sounds marking the dual is quite distinct: the combination wo in two and the long vowel in both are good examples of the vestigial dual persisting in English.

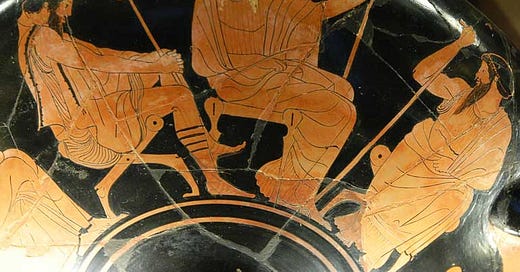

Classical Greek retained a limited use of the dual and Homeric Greek preserves it here and there. The most striking place where it shows up in the Iliad is in describing the movement of two heralds from one place to another. So, when Agamemnon sends heralds to retrieve the captive woman Briseis from Achilles in book 1 of the Iliad, we find dual forms for their pronouns and their verbal endings.

Let me start by setting out the problem. In Iliad 9, Achilles has been withdrawn from the conflict for 8 books of the epic and the situation looks pretty dire for the Achaeans. Agamemnon, at the advice of the elderly Nestor, sends an embassy to Achilles to plead with him to return, offering him compensation and further promises as inducement. Here’s the passage in English and Greek, with relevant plural forms in bold and dual forms in bold italics (Iliad 9.168-198):

Homer, Iliad 9.168-198

Let Phoinix, dear to Zeus, lead first of all

And then great Ajax and shining Odysseus.

And the heralds Odios and Eurubates should follow together.

Wash your hands and have everyone pray

So we can be pleasing to Zeus, if he takes pity on us.So he spoke and this speech was satisfactory to everyone.

The heralds immediately poured water over their hands

And the servants filled their cups with wine.

And then they distributed the cups to everyone

And then they made a libation and drank to their fill.

They left from Agamemnon’s, son of Atreus’ dwelling.

Gerenian Nestor, the horseman, was giving them advice,

Stopping to prepare each one, but Odysseus especially,

How to try to persuade the blameless son of Peleus.The two of them went along the strand of the much-resounding sea,

Both praying much to the earth-shaker Poseidon

That they might easily persuade the great thoughts of Aiakos’ grandson.

When the two of them arrived at the ships and the dwellings of the Myrmidons

They found him there delighting his heart with a clear-voiced lyre,

A well-made, beautiful one, set on a silver bridge.

Achilles stole it when he sacked and destroyed the city of Eetion.

He was pleasing his heart with it, and was singing the famous tales of men.

Patroklos was sitting there in silence across from him,

Waiting for Aiakos’ grandson to stop singing.The two of them were walking first, but shining Odysseus was leading.

And they stood in front of him. When Achilles saw them, he rose

With the lyre in his hand, leaving the place where he had been sitting.

Patroklos rose at the same time, when he saw the men.

As he welcomed those two, swift-footed Achilles addressed them.“Welcome [you too]–really, dear friends two have come–the need must be great,

When these two [come] who are dearest of the Achaeans to me, even when I am angry.”Φοῖνιξ μὲν πρώτιστα Διῒ φίλος ἡγησάσθω,

αὐτὰρ ἔπειτ’ Αἴας τε μέγας καὶ δῖος ᾿Οδυσσεύς·

κηρύκων δ’ ᾿Οδίος τε καὶ Εὐρυβάτης ἅμ’ ἑπέσθων.

φέρτε δὲ χερσὶν ὕδωρ, εὐφημῆσαί τε κέλεσθε,

ὄφρα Διὶ Κρονίδῃ ἀρησόμεθ’, αἴ κ’ ἐλεήσῃ.

῝Ως φάτο, τοῖσι δὲ πᾶσιν ἑαδότα μῦθον ἔειπεν.

αὐτίκα κήρυκες μὲν ὕδωρ ἐπὶ χεῖρας ἔχευαν,

κοῦροι δὲ κρητῆρας ἐπεστέψαντο ποτοῖο,

νώμησαν δ’ ἄρα πᾶσιν ἐπαρξάμενοι δεπάεσσιν.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ σπεῖσάν τ’ ἔπιόν θ’ ὅσον ἤθελε θυμός,

ὁρμῶντ’ ἐκ κλισίης ᾿Αγαμέμνονος ᾿Ατρεΐδαο.

τοῖσι δὲ πόλλ’ ἐπέτελλε Γερήνιος ἱππότα Νέστωρ

δενδίλλων ἐς ἕκαστον, ᾿Οδυσσῆϊ δὲ μάλιστα,

πειρᾶν ὡς πεπίθοιεν ἀμύμονα Πηλεΐωνα.Τὼ δὲ βάτην παρὰ θῖνα πολυφλοίσβοιο θαλάσσης

πολλὰ μάλ’ εὐχομένω γαιηόχῳ ἐννοσιγαίῳ

ῥηϊδίως πεπιθεῖν μεγάλας φρένας Αἰακίδαο.

Μυρμιδόνων δ’ ἐπί τε κλισίας καὶ νῆας ἱκέσθην,

τὸν δ’ εὗρον φρένα τερπόμενον φόρμιγγι λιγείῃ

καλῇ δαιδαλέῃ, ἐπὶ δ’ ἀργύρεον ζυγὸν ἦεν,

τὴν ἄρετ’ ἐξ ἐνάρων πόλιν ᾿Ηετίωνος ὀλέσσας·

τῇ ὅ γε θυμὸν ἔτερπεν, ἄειδε δ’ ἄρα κλέα ἀνδρῶν.

Πάτροκλος δέ οἱ οἶος ἐναντίος ἧστο σιωπῇ,

δέγμενος Αἰακίδην ὁπότε λήξειεν ἀείδων,

τὼ δὲ βάτην προτέρω, ἡγεῖτο δὲ δῖος ᾿Οδυσσεύς,

στὰν δὲ πρόσθ’ αὐτοῖο· ταφὼν δ’ ἀνόρουσεν ᾿Αχιλλεὺς

αὐτῇ σὺν φόρμιγγι λιπὼν ἕδος ἔνθα θάασσεν.

ὣς δ’ αὔτως Πάτροκλος, ἐπεὶ ἴδε φῶτας, ἀνέστη.

τὼ καὶ δεικνύμενος προσέφη πόδας ὠκὺς ᾿Αχιλλεύς·

χαίρετον· ἦ φίλοι ἄνδρες ἱκάνετον ἦ τι μάλα χρεώ,

οἵ μοι σκυζομένῳ περ ᾿Αχαιῶν φίλτατοί ἐστον.

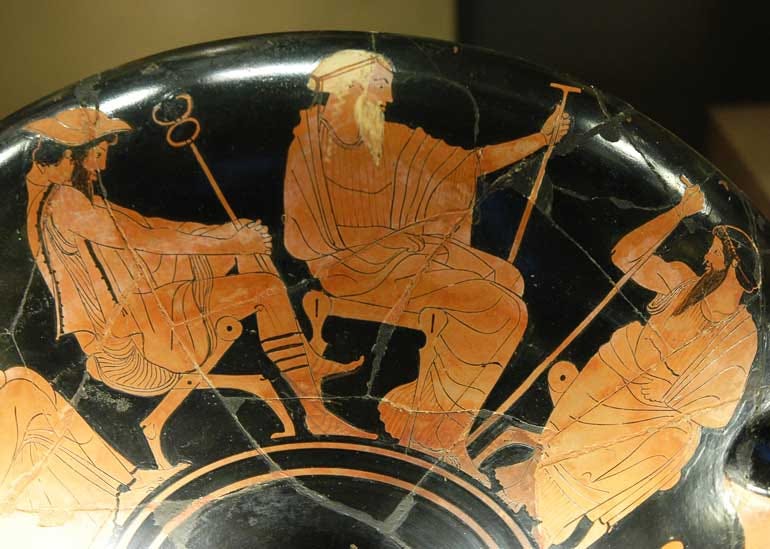

The embassy includes three speakers, Odysseus, Achilles’ older ‘tutor’ Phoenix, and his cousin, the powerful warrior, Ajax the son of Telamon. The two heralds accompany them as well. Yet the pronouns and verbal forms that describe them move between dual and plural forms. The grammarian responds that this is incorrect because there are at least five entities involved here. Modern responses over the past century have been:

The text needs to be fixed, the duals have come from an older/different version of the poem that had a smaller embassy (with several variations)

The traditional use is imperfect, the dual is being used for groups. Some scholiasts suggest that audiences would have just used the dual for the plural

The dual herald scene is merely formulaic and has been left in without regard for changes in the evolution of the narrative

The text is focalized in some way, showing Achilles (e.g.) refusing to acknowledge the presence of someone he dislikes (Odysseus, see Nagy 1979) or focusing on two people he does like (Phoenix and Ajax, Martin 1989)

The text is jarring on purpose, highlighting that something is wrong with this scene

Ancient commentators seem less bothered by the alternation in forms: an ancient scholiast suggests that the first dual form refers to Ajax and Odysseus because Phoinix hangs back to get more instruction from Nestor (Schol ad. Il. 9.182). Of course, this interpretation doesn’t even try to explain what happened to the actual heralds who were sent along with the embassy. Yet the interaction of forms seems to give some support to a complex reading. The number and entanglement of the forms makes interpolation seem unlikely (if not ludicrous) as an explanation. Consider, for example this brief passage from book 7 where heralds step forward to stop the duel between Ajax and Hektor:

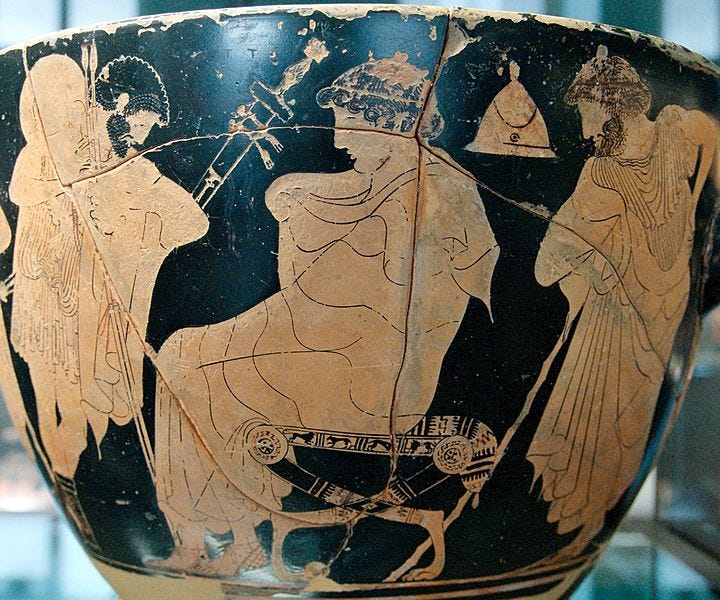

Homer Iliad 7.279-282

“Dear children, don’t wage war or fight any more.

Cloud-gathering Zeus loves you both,

And you are both warriors. All of us here certainly know this.

Night is already here: it is good to concede to night too.”μηκέτι παῖδε φίλω πολεμίζετε μηδὲ μάχεσθον·

ἀμφοτέρω γὰρ σφῶϊ φιλεῖ νεφεληγερέτα Ζεύς,

ἄμφω δ’ αἰχμητά· τό γε δὴ καὶ ἴδμεν ἅπαντες.

νὺξ δ’ ἤδη τελέθει· ἀγαθὸν καὶ νυκτὶ πιθέσθαι.

Here we have a lone plural form (polemizete) paired with a dual imperative (makhesthon). The manuscript traditions show some effort to change the dual imperative to a plural to match with the first polemizete, but no record that I can see of attempts to correct the plural to a dual. Plural forms can apply to two. Indeed, in many cases where there are multiple dual forms used in a passage there tends to be frequent recourse to plurals.

But the issue here is not a plural form being used for two figures, but the unclear antecedents for the dual forms as they are. It is not common for dual forms to be applied to more than two figures. I have presented the responses above in a sequence that I see as both historical (in terms of traditions of literary criticism) and evolutionary. The first response–that the text is wrong–assumes infidelity in the transmission from the past and entrusts modern interpreters with the competence to identify errors and ‘correct’ them. The second response moves from morphological to functional, positing that ancient performers might have ‘misused’ the dual for present during a period of linguistic change. Neither of these suggestions are supported by the textual traditions which preserve the duals.

The final three answers depend upon the sense of error explored in the first two: first, a greater understanding of oral-formulaic poetry extends the Parryan suggestion that some forms are merely functional and do not express context specific meaning (#3) while the second option models a complex style of reading/reception that suggests the audience understands the misuse of the dual to evoke the internal thoughts/emotions of the character Achilles in one way or another. The third explanation is harder to defend based on how integrated the dual forms are in the passage: the dual is used to describe travel to Achilles’ tent, then the scene shifts to Achilles playing a lyre and Patroklos waiting for him to stop followed again by dual forms with what seems like an enigmatic line “and so they both were walking forth, and shining Odysseus was leading” (tō de batēn proterō, hēgeito de dios Odusseus).

Ancient commentary remains nonplussed: Odysseus is first of two, the line makes that clear, and Phoinix is following somewhere behind. Nagy’s and Martin’s explanations are attractive and they respond well to the awkward movement between dual and plural forms as well as Achilles’ specific use of the dual in hailing the embassy with a bittersweet observation. I like the idea of taking these two together, leaving it up to audiences to decode Achilles’ enigmatic greeting.

Responses #4 and 5 are not necessarily exclusive. The final option builds on the local context of the Iliad and sees the type scene as functioning within that narrative but with some expectation that audiences know the forms and the conventions. As others have argued, the use of the duals to signal the movement of heralds is traditional and functional in a compositional sense because it moves the action of the narrative from one place to another. In the Iliad, the herald scene marks a movement from one camp to another, building on what I believe is its larger conventional use apart from composition which is to mark the movement from one political space, or one sphere of authority to another. When Agamemnon sends the heralds in book 1 to retrieve Briseis, the action as well as the language further marks Akhilles’ separation from the Achaean coalition. In book 9, the situation remains the same–Akhilles is essentially operating in a different power-structure–but the embassy is an attempt to address the difference. The trio sent along with the heralds as ambassadors are simultaneously friends and foreign agents. Appropriately, the conventional language of epic reflects this tension by interposing the duals and reflecting the confused situation.

Most of the responses above except for the first two are valid from the perspective of ancient audiences. The first two explanations–that the text is wrong or the usage is wrong–selectively accept the validity of some of the text but not that they find challenging for interpretive reasons or assume a simplicity on the part of ancient audiences (and many generations in between). The subsequent responses, however, credit a creative intention rather than the collaborative ecosystem of meaning available to Homeric performance.

In the telling of epic tales, it may well have been customary to manipulate conventional language through creative misuse; and yet, if audiences are not experienced enough of the forms or attentive enough to the patterns, such usage would not likely be sustained. Audiences (like the ancient scholar) imagine Phoinix lagging behind, or Achilles focusing just on one character, or sense the pattern of alienation and separation that makes it necessary to treat Achilles as a foreign entity and not an ally. So, while the text relies on audience competency with epic conventions, this specific articulation also allows for depth of characterization in this moment: The final three interpretive options cannot be fully disambiguated. Although we may argue for greater weight to the typological argument–that audiences would understand the complicated marking of Achilles as a potential enemy through this disjuncture–we cannot dismiss the tension between that larger structural meaning and the immediate force of Achilles’ speech, inviting us to see the use of the dual as a character choice.

Bibliography

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know. See Lesser 2022 for the most recent recent bibliography and discussion. Cf. Griffin 1995: 51–53. Scodel 2002: 160–71 and Louden 2006: 120–34 represent more recent readings.

Griffin, Jasper. 1995. Iliad, Book Nine. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kazazis, Deborah B. & Kazazis, John N. (1991). Iliad 9, the duals and Homeric compositional technique. Επιστημονική Επετηρίδα της Φιλοσοφικής Σχολής [του Αριστοτελείου Πανεπιστημίου Θεσσαλονίκης]. Tεύχος Τμήματος Φιλολογίας, 1, 11-45.

Lesser, Rachel H. 2022. Desire in the Iliad. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Louden, D. Bruce (2002). Eurybates, Odysseus, and the duals in Book 9 of the « Iliad ». Colby Quarterly, 38(1), 62-76.

Louden, D. Bruce (2006). The « Iliad » :: structure, myth, and meaning. Baltimore (Md.): Johns Hopkins University Pr.

Martin, Richard. 1989. The Language of Heroes: Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Nagy, Gregory. 1979. The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Scodel, Ruth. 2002. Listening to Homer: Tradition, Narrative, and Audience. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Segal, Charles (1968). The embassy and the duals of Iliad ix,182-198. Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, IX, 101-114.

Thornton, Agathe. “Once Again, the Duals in Book 9 of the Iliad.” Glotta 56, no. 1/2 (1978): 1–4. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40266418.

Wyatt, William F. “The Embassy and the Duals in Iliad 9.” The American Journal of Philology 106, no. 4 (1985): 399–408. https://doi.org/10.2307/295192.