This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 21. Here is a link to the overview of Iliad 20 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 21 follows book 20 as Achilles rampages over the battlefield in search of Hektor. As mentioned in discussing book 20, the two movements together serve both to delay the anticipated clash between Achilles and Hektor and also to depict the extremes to which Achilles’ rage will take him. Where book 20 features the hero facing another son of a goddess (Aeneas) and engages the Iliad with other heroic traditions, book 21 takes the violence to a cosmic scale. Achilles goes from slaughtering nameless young men to refusing to spare a suppliant, to fighting with gods.

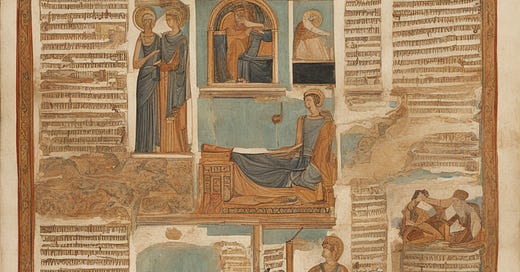

If Achilles has superhuman strength and his mênis has the potential to destabilize the universe, then book 21 dramatizes just how dangerous he is by invoking narrative themes of theomachy. His onslaught brings him into conflict with an anthropomorphized river (Skamandros) which he begins to lose, resulting in another appeal to the gods. When Hephaistos enters the fray to counter the river, it nearly breaks apart the fabric of the narrative, eliciting a battle between Athena and Ares. In this back and forth, the epic not only echoes motifs from tales of gigantomachy and titanomachy, but it uses language and imagery that may have reminded some audiences of the tales of Herakles.

At the same time, the events of book 21 recall earlier moments in the Iliad, from Achilles’ initial pleas in book 1 through the near theomachy of book 6, centered around the actions of Diomedes. Here, the gods eventually decide not to continue the fighting. When Poseidon and Apollo decline to battle one another, they confirm that there will be no proxy succession battle and there will be no cosmic disorder. The threat of Achilles is ultimately contained to the mortal realm, affirming the Iliad’s part in a narrative tradition that enacts and justifies the separation between the worlds of gods and humans.

Each of these narrative concerns adds something to the themes I have outlined in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions. Among these, however, I think book 21 speaks most directly to narrative traditions, Gods and humans, and heroism.

Judging Achilles

One of the chief challenges of the Iliad’s second half—if not of the entire epic—is establishing just what we are supposed to think of Achilles. There are no simple answers at any point in the epic as he moves from frustratingly reactive in book 1 to almost persuasively reflective in book 9 to concerned but recalcitrant in books 11 and 16 and finally a force like nothing else but a god once he returns to the battlefield. Book 20 showed that even the best of the mortals—a demigod!—is no match for Thetis’ son. Book 21 takes it one step further.

Homer, Iliad 21.17-33

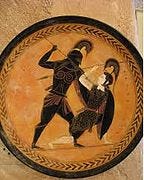

“Then godly Achilles left his spear there on the bank,

Leaning on the tamarisks and he leapt into the river,

Holding only his sword as he devised wicked deeds in his thoughts.

And he was striking constantly. An unseemly groan rose up

From the people he killed with the sword. And the water grew red with blood.

As when other fish fill the hollows of a safe harbor

When they are fleeing in front of a great-jawed dolphin

Out of fear, since it eats up whatever it catches,

So too did the Trojans cower in the currents of the terrible river

Right beneath the banks. But when he tired out his hands in the killing,

Achilles took twelve young men out of the river alive

As payback for the death of Menoitios’ son Patroklos.

He let them out and they were stunned like fawns.

He bound their hands behind them with the well-twisted belts

They were carrying themselves to cinch their tunics.

He handed them over to his attendants to take to the hollow ships.

Then he sprang back into action again, eager to murder some more.”Αὐτὰρ ὃ διογενὴς δόρυ μὲν λίπεν αὐτοῦ ἐπ’ ὄχθῃ

κεκλιμένον μυρίκῃσιν, ὃ δ’ ἔσθορε δαίμονι ἶσος

φάσγανον οἶον ἔχων, κακὰ δὲ φρεσὶ μήδετο ἔργα,

τύπτε δ’ ἐπιστροφάδην· τῶν δὲ στόνος ὄρνυτ’ ἀεικὴς

ἄορι θεινομένων, ἐρυθαίνετο δ’ αἵματι ὕδωρ.

ὡς δ’ ὑπὸ δελφῖνος μεγακήτεος ἰχθύες ἄλλοι

φεύγοντες πιμπλᾶσι μυχοὺς λιμένος εὐόρμου

δειδιότες· μάλα γάρ τε κατεσθίει ὅν κε λάβῃσιν·

ὣς Τρῶες ποταμοῖο κατὰ δεινοῖο ῥέεθρα

πτῶσσον ὑπὸ κρημνούς. ὃ δ’ ἐπεὶ κάμε χεῖρας ἐναίρων,

ζωοὺς ἐκ ποταμοῖο δυώδεκα λέξατο κούρους

ποινὴν Πατρόκλοιο Μενοιτιάδαο θανόντος·

τοὺς ἐξῆγε θύραζε τεθηπότας ἠΰτε νεβρούς,

δῆσε δ’ ὀπίσσω χεῖρας ἐϋτμήτοισιν ἱμᾶσι,

τοὺς αὐτοὶ φορέεσκον ἐπὶ στρεπτοῖσι χιτῶσι,

δῶκε δ’ ἑταίροισιν κατάγειν κοίλας ἐπὶ νῆας.

αὐτὰρ ὃ ἂψ ἐπόρουσε δαϊζέμεναι μενεαίνων.

The simile here is memorable, but it may strike modern readers as a little odd. We don’t often think of dolphins as bloody murderers. One scholion, however, expands on the comparison’s aptness based on its location.

Schol. bT Ad Hom. Il. 21.22-24

“The [elements] of the comparison work really well. On the one hand, the pursuer is on land, but those who are fleeing are pressed together into the river. The poem previously compared him to a fire and them to locusts [21.12-140]. But when the pursuer and the pursued are in the water, it harmonizes them to the newly established space.”

καλῶς τὰ τῆς παραβολῆς. ὅτε μὲν γὰρ ὁ διώκων ἐπὶ γῆς ἦν, οἱ δὲ φεύγοντες εἰς τὸν ποταμὸν συνωθοῦντο, τὸν μὲν πυρί, τοὺς δὲ ἀκρίσιν ὡμοίωσεν· ὅτε δὲ ἐν ὕδατι ὁ διώκων καὶ οἱ διωκόμενοι, πρὸς τὸν ὑποκείμενον τόπον ἡ παραβολὴ συνᾴδει.

Schol. T ad Hom. Il. 21.22

“The comparison to a dolphin is well-put. For Achilles the son of a sea-god. The narrative says “the other [fish]” because a dolphin is a fish.”

καλῶς δὲ καὶ δελφῖνι εἴκασται· θαλασσίας γὰρ δαίμονος υἱός. ὡς ἰχθύος δὲ ὄντος τοῦ δελφῖνος τὸ ἄλλοι (22) εἶπεν.

Ok, so the first scholion seems to show no interest in dolphins whatsoever. But it is interested in how the local space of the narrative corresponds to the frame of the simile. Such a ‘harmony’ between form and content directs me to think about what we can think about the correspondence between the actions Achilles undertakes and their narrative framing.

This scene, where Achilles captures the twelve Trojan youths he will sacrifice on Patroklos’ grave later on in the epic, is nearly understated compared to what happens later on in book 21. But it stands for me in the same notional space as the murder of the suitors in the Odyssey and the hanging of the enslaved women. One of my concerns for all of these scenes is how we as modern readers should receive the Homeric drama: are these scenes exploration of excessive violence, of transgressive action, or are they merely vivid depictions of the kinds of actions heroes commit in the heat of battle. To put it differently, how do we understand the Homeric narrator’s tone here. Often, when discussing the Odyssey, scholars couch Odysseus’ vengeance against the suitors and his son’s treatment of the enslaved women as justified as part of the epic’s homecoming narrative. I think this kind of reading is both insensitive to the language of Homeric poetry and naive concerning the complexity of its capacity to convey ‘traditional’ actions in a negative light.

I am certain that Odysseus’ homecoming vengeance was understood as going to far and initiating a potential endless cycle of violence. Similarly, I think that Achilles’ violence in books 21-23 is marked as going way too far, both to characterize the absolute ruin caused by his raise and also to implicitly frame the danger represented by a figure possessing so much power that he cannot be restrained by other mortals and amounts to a threat even to the gods. The story of the Iliad is not about the excellence of heroes; it is about the danger they represent and the damage they cause.

When we talk about excessive violence in the Iliad, we sometimes miss out on how the epic itself marks some of it as exceptional or transgressive. Achilles’ capture of the Trojan youths is prefaced by the narratives seemingly blithe “then he was devising wicked deeds”. The combination kaka erga implies some judgment on the part of the narrative, but kakon can at times mark a deed as merely base or ignoble. The combination with the verb mêdeto seems to invoke a pattern in the Iliad around Achilles’ actions in particular. In book 22, when Achilles is about to pierce Hektor’s ankles and drag his body around the city, he is described as “devising unseemly deeds against shining Hektor” (῏Η ῥα, καὶ ῞Εκτορα δῖον ἀεικέα μήδετο ἔργα, 22.395=23.24) and then, again, in book 23, before he actually sacrifices the twelve Trojan youths, the same phrase as in 21 appears, marking the sacrifice in particular as transgressive (...κακὰ δὲ φρεσὶ μήδετο ἔργα, 23. 176).

While the adjective modifying erga changes, there’s something in the verb in that penultimate position that marks supernatural agency. In the Odyssey, mêdeto appears in this position when ascribing the responsibility for actions to a generic god or to Zeus. In the Iliad, only Zeus (x2) and Achilles (x4) are subjects of this verb in this position and for it is localized to his sacrifice of the Trojan youths and his mistreatment of Hektor’s corpse. For Zeus, it marks Agamemnon’s ignorance about Zeus’ actual plans in book 2 (νήπιος, οὐδὲ τὰ ᾔδη ἅ ῥα Ζεὺς μήδετο ἔργα, 2.38) and Zeus’ preparations for the return to war in book 7 (παννύχιος δέ σφιν κακὰ μήδετο μητίετα Ζεὺς, 7.478).

The Iliadic use of this phrasal shape, then, makes a connection between Zeus’ prosecution of his plan within the Iliad and Achilles’ superhuman destruction. While narrative judgment in each case may be subject to some debate, it seems clear to me that the cumulative effect is to acknowledge the particular cruelty of the events of the Iliad (as requested by Achilles) and the excess of heroic action. The Homeric narrative does not clearly state that Achilles criminal acts of horror, but I cannot imagine how any attentive audience would not hear such an implication.

One scholion—and I am not sure I have understood it completely—seems to say that these scenes are motivated in part by a need to do something different, now that the Iliad has done everything it could with fighting on the plain, around the walls, and among the ships. It also adds that there’s no way “barbarians” would be worthy of fighting him, so that it makes sense to pit Achilles against gods instead.

Schol. bT ad Hom. Il. 21.18a ex

“Once he went through every kind of battle in the plain, around the fortification, and among the ships, now [the poet] has devised something new in Achilles’ onslaught in the battle along the river, not only in emphasizing the single idea, but adding new/strange compositions to the poetry. For he contrived this fourth kind of battle for the closing of his poem, since he does not see barbarians as worthy of fighting Achilles; and it ends the poem in a strange incompleteness, and he introduces the battle of the gods and the river, taking as a convenient starting point the constraint [imposed on the river] by the corpses”

πᾶσαν ἰδέαν μάχης διελθὼν ἐν τῷ πεδίῳ καὶ περὶ τὸ τεῖχος καὶ ἐν ταῖς ναυσί, καινόν τι ἐξεῦρεν ἐπὶ τῇ ᾿Αχιλλέως ἐξόδῳ τὴν παρὰ τῷ ποταμῷ μάχην,

οὐ μόνον τὴν μονοείδειαν περιϊστάμενος, ἀλλὰ καὶ καινὰς διαθέσεις ἐπεισφέρων τῇ ποιήσει· τετάρτην γὰρ ταύτην συνιστὰς μάχην ἐπὶ λήξει τῆς ποιήσεως, ἐπεὶ μὴ ἀξιομάχους οἶδε βαρβάρους ᾿Αχιλλεῖ, καὶ ἄτοπον εἰς ἀκατέργαστον λῆξαι τὴν ποίησιν, θεῶν τε μάχην παρεισάγει καὶ τὸν ποταμὸν †καθίστησιν†, εὔλογον ἀφορμὴν λαβὼν τὴν ἀπὸ τῶν νεκρῶν στένωσιν

Another makes it clear that at least some ancient readers saw the behavior as excessive.

Schol. bT ad Hom Il. 21. 27

This passage is here because he is going to introduce later the sacrifice called the dôdecad. The poem presents a great excess through this, showing that he selects the prisoners of a certain kind and number and that he binds these men together into one group, tying up their hands as if slaves captured in war.”

εἰς θυσίαν μέλλων παριστάνειν τὴν καλουμένην δωδεκάδα. μεγάλην δὲ τὴν ὑπεροχὴν διὰ τούτου παρίστησιν, ἐπιλέξασθαι αὐτὸν τοὺς αἰχμαλώτους λέγων οἵους καὶ ὅσους ἐβούλετο, εἶτα καὶ τούτους καθ' ἕνα συνδῆσαι, ὥσπερ ἀνδράποδα προτείνοντας τὰς χεῖρας (cf. Φ 30).

Reading Questions for Book 21

What does the conversation between Achilles and Lykaon contribute to themes of heroism, violence, and convention?

What does Achilles’ battle with the river add to our understanding of the Iliad?

Why do the gods fight each other directly in this book and how does this compare to other divine conflicts (e.g. in books 6, 14 and 15)?

Love the scholia.