This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 14. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

As I mention in the first post about Iliad 14, the book provides a structure that is built around three basic movements: the crisis of leadership among the Achaeans, resolved by Diomedes; a rallying of the Greeks on the field, led by Poseidon; the Dios apate, or deduction of Zeus, including Hera’s preparations and their Idaean assignation.

These scenes are connected both in terms of plot and theme around resistance to Zeus’ plan: the Greek captains rally and correct Agamemnon to maintain some unity; Poseidon intervenes to help the Greeks resist (and even wound) Hektor; and Hera, in coordination with Poseidon, distracts Zeus in order to support their resistance. Altogether, these three movements take us from the very serious human challenges of the opening panic, through a somewhat surreal but still ‘epic’ battle scene mixed with the gods, until it terminates in a comic, other-worldly Romantic tryst. There’s a unity and a wholeness to the book that reminds me of the three-movements in book 6.

Such neatness, if it can be called such, invites questions about design and the relationship between the parts of the Iliad and the whole. Anyone who picks up a translation of either epic today finds them neatly divided into 24 books each (even though the Iliad is 3000 lines longer than the Odyssey. What makes this a little suspicious is that in ancient Greek, the books are named after the 24 available letters of the alphabet. It is highly unlikely, moreover, that the division of books was established in the Archaic and classical period since once the Greeks adopted the 22 letters of the Phoenician alphabet, local dialects often had more than 24 letters (including variations like qoppa, digamma) and would assign received symbols (those we know for psi, ksi, and khi) to different sounds. Indeed, the standard Ionic alphabet was not adopted in Athens until after the Peloponnesian War (c. 403 BCE).

Pseudo-Plutarch, De Homero 2.4

“Homer has two poems: the Iliad and the Odyssey, each of them is divided into the number of letters in the alphabet, not by the Poet himself, but by the scholars in Aristarchus’ school.”

Εἰσὶ δὲ αὐτοῦ ποιήσεις δύο, ᾿Ιλὰς καὶ ᾿Οδύσσεια, διῃρημένη ἑκατέρα εἰς τὸν ἀριθμὸν τῶν στοιχείων, οὐχ ὑπὸ αὐτοῦ τοῦ ποιητοῦ ἀλλ' ὑπὸ τῶν γραμματικῶν τῶν περὶ ᾿Αρίσταρχον.

So just how and where the book divisions of the Homeric epics came from has been something of a hot topic from time to time. The major arguments are:

The book divisions were there from the beginning, because the alphabet was adopted to write Homer down

The book divisions are features of smaller performance units

The book divisions were a product of Hellenistic editing, following the adoption of a regular alphabet and the impetus to present standard, synoptic versions of epic

The book divisions were a result of the process of dictating the poems: each one represents a day’s dictation, or something like that.

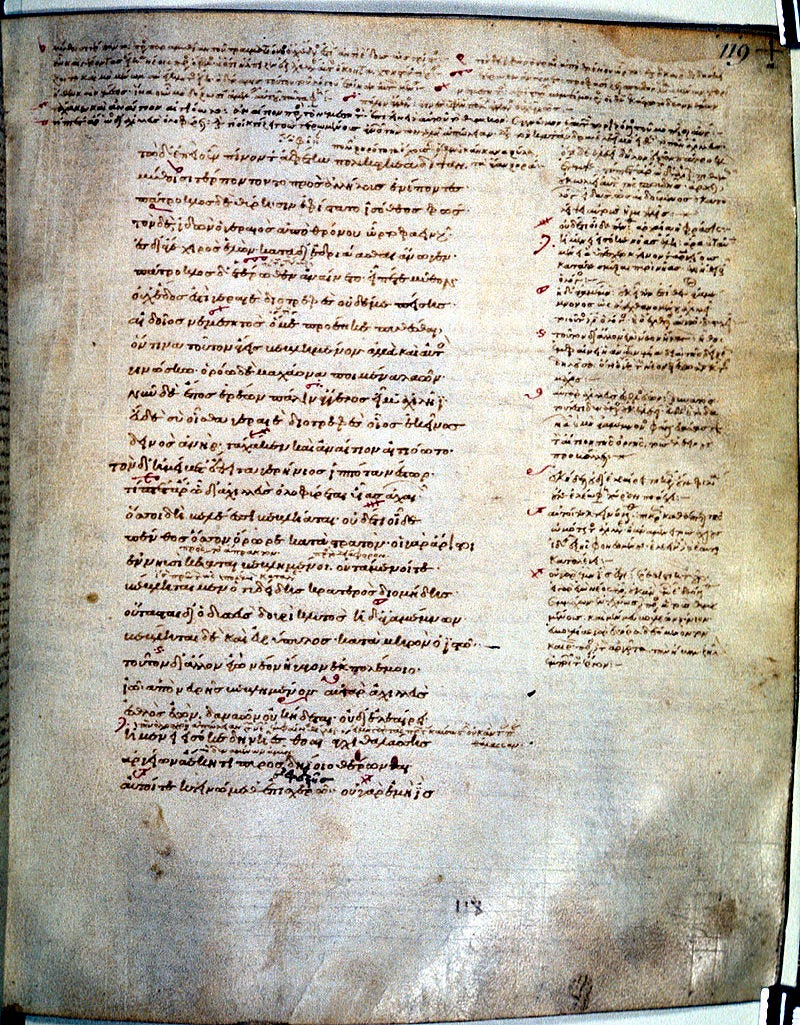

Part of an eleventh-century manuscript, "the Townley Homer". The writings on the top and right side are scholia.

What people call the ‘books’ of the Iliad often reveal some of their assumptions about their nature. Note, the passage above does not use the word biblion (although it is implied, I think). Other titles such as scrolls or rhapsodies see the performance units as possibly relating to scripts or readily performable episodes. I also worry about to what extent some of these models are divorced from the material reality of (1) the cost of transcription and copying and (2) a reading public accustomed to performance of epic.

There are challenges with each approach: we have no evidence of Alphabetic book distinctions before the Hellenistic period (when earlier authors talk about Homeric passages, they focus on episodes); we don’t have any evidence for book divisions as performance units, since many of the episodes referred to as potential performance pieces occupy parts of books rather than their whole; we have only anecdotal evidence supporting the creation of book divisions by Hellenistic editors, and that evidence is 3-5 centuries after the fact; and we have no direct evidence for the dictation and recording of the poems. Another early testimony about the book-divisions, discussed by Rene Nunlist, shows that early scholars emphasized the unity of the whole poems and saw the book divisions as sometimes artificial interventions.

The details of the arguments are interesting too. But here’s a summary of the issues from Steve Reece (2003):

2) All at once about ten years ago a great amount of attention began to be paid to the book divisions in the Homeric epics; more specifically, to how the twenty-four book divisions in our inherited texts of the Iliad and Odyssey are related to the historical performance units of these songs. The debate remains unresolved. On one end are those who regard the book divisions as reflections of breaks in the historic performance of an eighth- or seventh-century BCE bard. On the other end are those who regard them as Alexandrian—a result of serendipity (the fact that there are 24 letters in the Ionian alphabet) and, to a lesser degree, of the physical features of text-making during the Hellenistic period (the typical length of a papyrus roll). Somewhere in between are those who trace the book divisions to the first writing down of the epics in connection with their performance at one of the Greater Panathenaic Festivals in Athens in the late sixth century. Whenever, and for whatever reason, they occurred, most of the book divisions seem to have been chosen judiciously, coinciding with breaks in the narrative. Yet some clash with scene divisions, cutting right through a narrative segment or even a type-scene (e.g., Il. 5-6, 6-7, 18-19, 20-21; Od. 2-3, 3-4, 6-7, 8-9, 12-13, 13-14, 20-21). Hence there has developed some consensus among Homeric scholars that in performance a division into three or four major "movements" is to be preferred to the twenty-four book units. As a practical matter, I encourage my students to read through the book divisions of Homer, just as I encourage them, in their reading of other oral narratives, to disregard the artificial divisions imposed by textualization (verse, section, chapter, book divisions)—in the New Testament Gospels, for example. Not only does this practice better replicate the original performance units, but it also allows the modern reader to detect patterns and themes in the epic that are obfuscated by overadherence to book divisions. A recent and excellent summary of the debate on book divisions, with full appreciation of its implications for oral poetics, is Jensen 1999.

Scholars like Bruce Heiden (following others) argue with some efficacy for the structure of each book. Heiden argues (1998, 69)

“ The analysis will first consider the placement of the twenty-three 'book divisions'. It will show that all the scenes that immediately precede a 'book division' manifest a common feature, namely that they scarcely affect forthcoming events in the story. All the scenes that follow a book division' likewise display a common characteristic: these scenes have consequences that are immediately felt and continue to be felt at least 400 lines further into the story. Therefore, all of the twenty-three 'book divisions' occur at junctures of low-consequence and high consequence scenes. Moreover, every such juncture in the epic is the site of a 'book division'.

The second stage of the analysis will examine the textual segments that lie between ‘book divisions', i.e., the 'books' of the Iliad. It will show that in each 'book' the last event narrated is caused by the first, as are most of the events narrated in between. But the last event seldom completes a program implied by the first. Thus the 'books' of the Iliad display internal coherence, but only up to a point. They do not furnish a strong sense of closure. Instead their outline is marked by a sense of diversion in the narrative at the beginning of each.”

I think that close readings of many of the books bears out some of Heiden’s argumentation here, but the problem is what the cause of this is, by which I mean is this a feature of our efforts as interpreters and the impact that the Iliad’s contents have had on the history of literature in its wake shaping our expectations or is this a matter of intentional design.

Steve Reece, in a later piece, emphasizes that approaches like this in general double down on ignoring the performance origins of the poems (2011, 300-301):

“We may acknowledge the orality of Homeric epic, we may refer to it as performance, we may pay obeisance to the study of comparative oral traditions, but we remain addicted to our printed texts, our book divisions and line numbers, our apparatus critici, our concordances and lexica. We rarely try to reconstruct or even imagine a production of an epic performance.”

A combination of the work of Minna Skafte Jensen, Jonathan Ready, and Reece’s own fine essay ventures to imagine the performance context, but the first two tie it to the formation of the texts we have as well. (It is Jensen in her seminal debate from 1999 who suggests the book units are the product of a day’s transcription.)

Simonides, fr. 6.3

“Simonides said that Hesiod is a gardener while Homer is a garland-weaver—the first planted the legends of the heroes and gods and then the second braided them together into the garland of the Iliad and the Odyssey.”

Σιμωνίδης τὸν ῾Ησίοδον κηπουρὸν ἔλεγε, τὸν δὲ ῞Ομηρον στεφανηπλόκον, τὸν μὲν ὡς φυτεύσαντα τὰς περὶ θεῶν καὶ ἡρώων μυθολογίας, τὸν δὲ ὡς ἐξ αὐτῶν συμπλέξαντα τὸν᾿Ιλιάδος καὶ Οδυσσείας στέφανον.

By take on the major issues presented here is that the final three approaches are reconcilable from an evolutionary perspective. The evolutionary model for the creation of the Homeric epics (on which, see Nagy 2004 and Dué 2018), posits a movement from greater flexibility to greater fixity over time. If we imagine Homeric epic already existing notionally between episodic performances and monumental events involving multiple singers, we can see these episodes more or less coalescing around smaller performance units that could be stitched together in grander performance contexts. Any process of textualization would necessarily include stages of dictation and transcription providing performance units that were largely coherent as a whole and which would present different levels of internal coherency based in the individual performance. As the whole cultural phenomenon was transferred from performance contexts around the Greek speaking world to the libraries of the Hellenistic cities, they would achieve a textual fixity and polish that would harden, where possible, the joins between books.

Just as in my metaphor for the cultivation of crops or trees, Homeric poetry would have been adapted and shaped over time by the performance context, the intervention of transcription and textualization, and the actions of editors imposing regularity and uniformity typical of literary traditions.

Other explanations require a textual culture for the poems at a much earlier period. This model, as well, helps to explain the unified, yet still organic and largely asymmetric shape of a book like Iliad 14.

A starter bibliography on Homeric Book Divisions

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Bachvarova, Mary R. 2016. From Hittite to Homer: The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Campbell, Malcolm. “Apollonian and Homeric Book Division.” Mnemosyne 36, no. 1/2 (1983): 154–56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4431214.

Dué, Casey. 2018. Achilles Unbound: Multiformity and Tradition in the Homeric Epics. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

G. P. Goold. “Homer and the Alphabet.” Transactions of the American Philological Association, 91:272-91.

Graziosi, Barbara. 2002. Inventing Homer. Cambridge.

Bruce Heiden. “The Placement of ‘Book Divisions’ in the Iliad.” Journal of Hellenic Studies, 118:68-81.

Minna Skafte Jensen. "Dividing Homer: When and How Were the Iliad and the Odyssey Divided into Songs?" Symbolae Osloenses, 74:5-91.

Nagy, Gregory. 2004. Homer’s Text and Language. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Nünlist, René. “A Neglected Testimonium on the Homeric Book-Division.” Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 157 (2006): 47–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20191105.

Barry B. Powell. Homer and the Origin of the Greek Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Presss

Ready, Jonathan. 2019. Orality, Textuality, and the Homeric Epics. 2019.

Reece, Steve. "Homeric Studies." Oral Tradition, vol. 18 no. 1, 2003, p. 76-78. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/ort.2004.0035.

Reece, Steve. 2011. “Toward an Ethnopoetically Grounded Edition of Homer’s Odyssey.” Oral Tradition, 26/2 (2011): 299-326.