This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 22. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Once Achilles kills Hektor and starts to mistreat his body, the narrative provides the clearest judgment on his acts as possible by marking the treatment as shameful (ἀεικέα μήδετο ἔργα.) and then moving from his excess to the responses of the epic’s internal audience. Almost too late do we as the external viewers of the horror realize that Hektor’s death has been witnessed by his people and members of his family. In an echo of the first part of the book, we hear from Priam and then Hecuba as they begin their laments. The structure is in a way an expansion of the rhetorical rising tricolon: Priam and Hecuba are followed by a much longer segment that moves us toward Andromache.

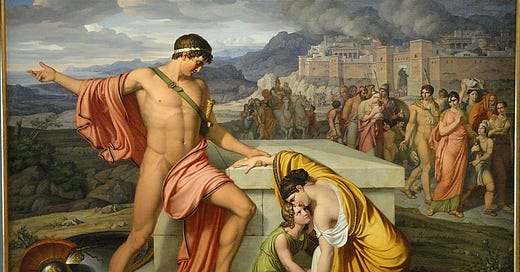

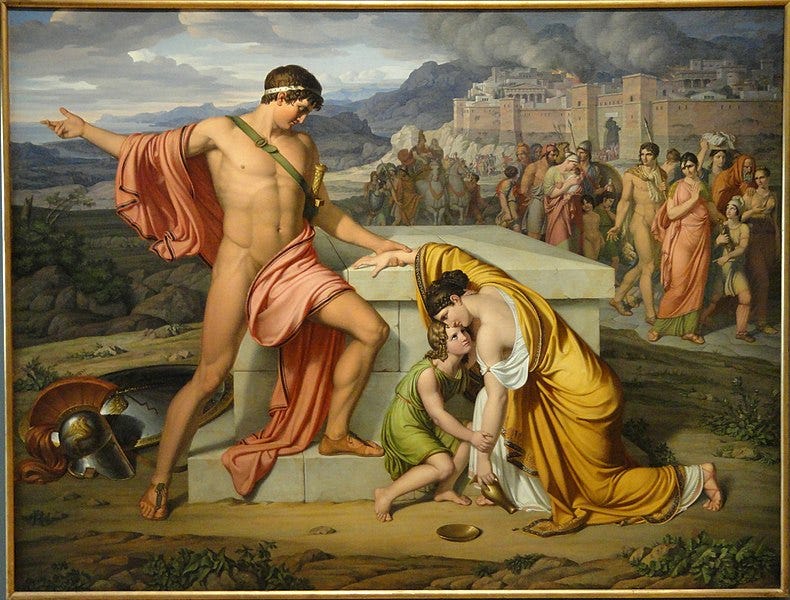

Andromache, as some audience members might recall, was last seen in book 6 when she was sent by Hektor back to her weaving. We find her near the end of book 22 weaving still. When the narrative takes us to her, she is calling for a bath to be drawn for her husband. But when she hears the sounds from without, she freezes, dropping the weaving from her hands. In a scene Charles Segal has described as an anagnorisis (the word Aristotle uses for recognition or realization in tragedy), Andromache is overcome, she faints, and needs the help of her attendants to go outside. She removes her veil, and is compared to a maenad “in a state of ecstatic frenzy” (as Christos Tsagalis puts it).

The prolonged setup accompanied by the description of grief’s impact on her body introduces one of the most remarkable speeches in Homer. Once so complex and moving, that if the epic’s political and reciprocal themes were not still left to be resolved, this might be the poem’s true end.

Iliad 22.482-507

“And now you go under the hidden places of the earth to Hades’ home,

But you leave me in hateful grief, a widow in our home—

And your child too, still an infant, the one we bore

You and I, ill-fated, Hektor, you will not be of any use to him

Since you have died, and he won’t be to you.For even if he should escape the Achaeans’ war of many tears,

Still there would be toil and griefs for this child afterward.

For others will deprive him of his lands.The day that makes a child an orphan separates him from his peers.

He looks down all the time; his cheeks are covered in tears;

And the child goes in need to his father’s friends,

Asking one for a cloak and another for a tunic.

He holds out his little cup while they pity him—

He can moisten his lips but never fill his hunger.A luckier child chases him from the feast,

Striking him with his hands and laying into him with words:

“Go away—your father doesn’t dine with us.”And the cheerful child will return to his widowed mother,

Astyanax, who used to eat only marrow and the rich fat

Of sheep as he sat on his father’s needs.

Then when sleep would come over him, he would stop playing

And rest on a bed in the arms of a nurse, his heart full

Of everything good on that soft bed.But now, he would suffer much once he has lost this dear father,

Astyanax, as the Trojans call him as a nickname,

For you alone defended their bulwarks and great walls.”νῦν δὲ σὺ μὲν ᾿Αΐδαο δόμους ὑπὸ κεύθεσι γαίης

ἔρχεαι, αὐτὰρ ἐμὲ στυγερῷ ἐνὶ πένθεϊ λείπεις

χήρην ἐν μεγάροισι· πάϊς δ’ ἔτι νήπιος αὔτως,

ὃν τέκομεν σύ τ’ ἐγώ τε δυσάμμοροι· οὔτε σὺ τούτῳ

ἔσσεαι ῞Εκτορ ὄνειαρ ἐπεὶ θάνες, οὔτε σοὶ οὗτος.

ἤν περ γὰρ πόλεμόν γε φύγῃ πολύδακρυν ᾿Αχαιῶν,

αἰεί τοι τούτῳ γε πόνος καὶ κήδε’ ὀπίσσω

ἔσσοντ’· ἄλλοι γάρ οἱ ἀπουρίσσουσιν ἀρούρας.

ἦμαρ δ’ ὀρφανικὸν παναφήλικα παῖδα τίθησι·

πάντα δ’ ὑπεμνήμυκε, δεδάκρυνται δὲ παρειαί,

δευόμενος δέ τ’ ἄνεισι πάϊς ἐς πατρὸς ἑταίρους,

ἄλλον μὲν χλαίνης ἐρύων, ἄλλον δὲ χιτῶνος·

τῶν δ’ ἐλεησάντων κοτύλην τις τυτθὸν ἐπέσχε·

χείλεα μέν τ’ ἐδίην’, ὑπερῴην δ’ οὐκ ἐδίηνε.

τὸν δὲ καὶ ἀμφιθαλὴς ἐκ δαιτύος ἐστυφέλιξε

χερσὶν πεπλήγων καὶ ὀνειδείοισιν ἐνίσσων·

ἔρρ’ οὕτως· οὐ σός γε πατὴρ μεταδαίνυται ἡμῖν.

δακρυόεις δέ τ’ ἄνεισι πάϊς ἐς μητέρα χήρην

᾿Αστυάναξ, ὃς πρὶν μὲν ἑοῦ ἐπὶ γούνασι πατρὸς

μυελὸν οἶον ἔδεσκε καὶ οἰῶν πίονα δημόν·

αὐτὰρ ὅθ’ ὕπνος ἕλοι, παύσαιτό τε νηπιαχεύων,

εὕδεσκ’ ἐν λέκτροισιν ἐν ἀγκαλίδεσσι τιθήνης

εὐνῇ ἔνι μαλακῇ θαλέων ἐμπλησάμενος κῆρ·

νῦν δ’ ἂν πολλὰ πάθῃσι φίλου ἀπὸ πατρὸς ἁμαρτὼν

᾿Αστυάναξ, ὃν Τρῶες ἐπίκλησιν καλέουσιν·

οἶος γάρ σφιν ἔρυσο πύλας καὶ τείχεα μακρά.

In describing this speech from a narratological perspective, Rebecca Muich notes that even in her grief, Andromache seems to recede into her narrative, imagining someone else’s pain, creating a scene where “her own experiences do not figure into [the] story” (14). Her focus on Hektor’s place in book 6 and his absence in this first speech “seeks to stress the father’s role in grounding a child within a community” (14) and indicates, in part, that Andromache cannot see past the personal loss to her family unit and see the impact on the whole city (contrasting with Hektor’s earlier emphasis on his responsibility to the people).

I was profoundly moved by this speech for its vividness and terrible irony long before I was a parent myself. The first time I read this passage in Greek as I prepared for my PhD exams, I wept while completing it. As a parent now, I struggle even to think about reading it. The terrible irony of course is that Astyanax is actually killed by the victors before he can suffer the deprivations his mother predicts, although she does fear this fate:

Iliad 24.732–738

“You, child, will also either follow me

Where you will toil completing the wretched works

Of a cruel master or some Achaean will grab you

And throw you from the wall to your evil destruction

Because he still feels anger at Hektor killing his brother

Or father or son, since many a man of the Achaeans dined

On the endless earth under Hektor’s hands.”… σὺ δ’ αὖ τέκος ἢ ἐμοὶ αὐτῇ

ἕψεαι, ἔνθά κεν ἔργα ἀεικέα ἐργάζοιο

ἀθλεύων πρὸ ἄνακτος ἀμειλίχου, ἤ τις ᾿Αχαιῶν

ῥίψει χειρὸς ἑλὼν ἀπὸ πύργου λυγρὸν ὄλεθρον

χωόμενος, ᾧ δή που ἀδελφεὸν ἔκτανεν ῞Εκτωρ

ἢ πατέρ’ ἠὲ καὶ υἱόν, ἐπεὶ μάλα πολλοὶ ᾿Αχαιῶν

῞Εκτορος ἐν παλάμῃσιν ὀδὰξ ἕλον ἄσπετον οὖδας.

In the popular tradition the one who carries out the killing of Astyanax is Odysseus, that ‘hero’ of that other epic who gets to go home to his own son and father. If the way we talk about and treat our enemies dehumanizes them—and us—what does it mean when we murder, torture, or harm children? This is not an ‘academic’ question in the Iliad. As I discuss in a post on book 6, transgressive violence– ‘war crimes’--is central to the epic’s exploration of what rage and revenge does to people. When Agamemnon tells his brother they will kill even children in the wombs, it anticipates Astyanax’s future death and increases the pain we feel for Andromache in book 6.

In the future Andromache imagines, Astyanax is marginalized even among his own people by the loss of his father–he loses his status, his friends, and his former happiness. But in a foreign land, he loses all hope of happiness–he is a slave to another if he is lucky to be alive. The reality is, of course, worse–given that nearly every account of what happens in the sack of Troy (or after) has Astyanax dying terribly.

And the future is not much better for Andromache. Her pairing with Hektor as Achilles’ opposite is matched with her possession by Achilles’ son, Neoptolemos, who is awarded her in his father’s stead. Andromache bears children to the son of her husband’s killer (and her story is explored in different ways in Euripides’ Andromache and Trojan Women.

In a moving article, Franco Maiullari suggests that taking three of Andromache’s speeches together helps us see here as a character suffering from trauma: first, the loss of her family (brothers, father, mother), described in dialogue in book 6; second, this speech from book 22, when she is described as in some kind of a trance before her speech. Maiullari focuses on Andromache’s collapse and the narrative’s description of her as nearly deed. And then, in the speech herself, her emphasis on her son instead of herself shows her fixating, looking away from the grief, but perhaps projecting her own experience as an orphan to her child’s future. The third speech is her final lament for Hektor, where she revisits many of the same themes, in a tighter, charged fashion. Maiullari suggests that Astyanax becomes a stand-in for both parents and, perhaps, for the lost future of the city: “Astyanax is the symbol of a childhood that will always remain in its potential state: a tragic repeated destiny for the mother and an unfulfilled promise for the father” (2016, 26).

Andromache’s imagined future hurts even more than it should because even this vision of suffering is less grievous than Astyanax’s actual death and Andromache’s passage into slavery and the sexual violence it implies. The image of the lonely child, separated from his peers is an echo of Andromache at that moment, bereft of her only family, looking forward to a future of begging and shame.

But it will be one without this precious son. And in the end, I think this is what we should take away from the Iliad–how violence destroys cities, how it takes away all that is good, and how the promises of goods and glory are empty and hollow in the face of irreparable loss. While we know all too well that the ability is about heroes and their futile rage, recent books by Emily Austin and Rachel Lesser remind us that epic is also about loss and desire for what can never be returned.

Children dying in war, murdered when they should be playing and dreaming, should be an unforgivable sin. They represent so many futures foreclosed, so much hope and potential undone for reasons that have nothing to do with them. But what is violence apart from unreasonable, unforgivable loss? The Iliad shows us this through the deaths of Patroklos, Hektor, and the future death of this child, the “lord of the city” through whose singular future we grieve the collapse of an entire people.

A short bibliography

Biondi, Francesca. “Il velo di Andromaca in Il. 22, 468-472 : analisi della tradizione esegetica antica.” Giornale Italiano di Filologia, vol. 69, 2017, pp. 11-25. Doi: 10.1484/J.GIF.5.114572

Emily P. Austin, Grief and the hero: the futility of longing in the Iliad. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021.

Dimock, Wai Chee. “After Troy: Homer, Euripides, total war.” Rethinking tragedy. Ed. Felski, Rita. Baltimore (Md.): Johns Hopkins University Pr., 2008. 66-81

Casey Dué. 2002. Homeric Variations on a Lament by Briseis.

Easterling, Patricia E.. “The tragic Homer.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies of the University of London, vol. XXXI, 1984, pp. 1-8. Doi: 10.1111/j.2041-5370.1984.tb00524.x

Karanika, Andromache. “Women’s tangible time: perceptions of continuity and rupture in female temporality in Homer.” Narratives of time and gender in antiquity. Eds. Eidinow, Esther and Maurizio, Lisa. London ; New York: Routledge, 2020. 13-27.

LEFKOWITZ, MARY R. “The Heroic Women of Greek Epic.” The American Scholar 56, no. 4 (1987): 503–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41211464.

Lesser, Rachel. 2022. Desire in the Iliad: The Force That Moves the Epic and Its Audience. Oxford.

Lohmann, Dieter. Die Andromache-Szenen der Ilias. Ansätze und Methoden der Homer-Interpretation. Spudasmata; XLII. Hildesheim: Olms, 1988.

Maiullari, Franco. “Andromache, a post-traumatic character in Homer.” Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica, N. S., no. 113, 2016, pp. 11-27.

Muich, Rebecca. “Focalization and Embedded Speech in Andromache’s Iliadic Laments.” Illinois Classical Studies, no. 35–36 (2011): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5406/illiclasstud.35-36.0001.

Segal, Charles. “Andromache's anagnorisis. Formulaic artistry in Iliad 22.437-476.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. LXXV, 1971, pp. 33-57.

Tsagalis, Christos. 2008. The Oral Palimpsest: Exploring Intertextuality in the Homeric Epics. Hellenic Studies Series 29. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.