This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 24. Some of the material near the end is from a book coming out at the end of this year from Yale University Press, Storylife: On Epic, Narrative, and Living Things. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

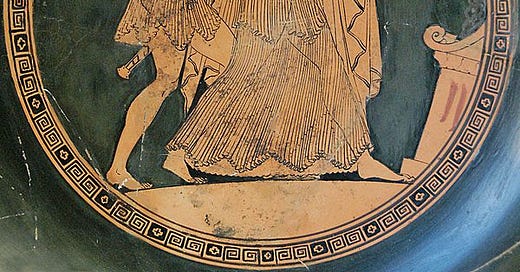

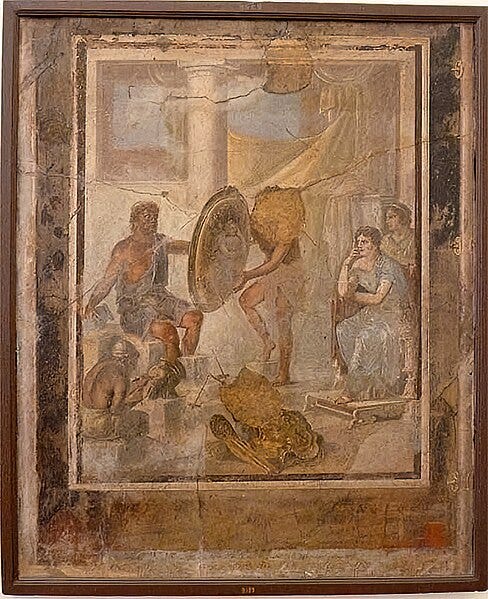

In an earlier post, I wrote about Priam’s journey to Achilles as a passage to a liminal space, but one dominated by death. This katabasis, guided by Hermes, is part funerary procession and part dream-like reverie. But before Priam starts his night-time crossing of the battlefield, we get to see Achilles in his place with his mother, who tries ever so briefly to remind him of life.

Homer, Iliad 24.128-37

Then his queen mother sat very close to him,

And she reached him with her hand as she spoke and named him:

“My child, how long will you consume your heart

Mourning and grieving [akheuon] and thinking nothing of food

Or bed. It is a good thing to have sex with a woman—

For you will not live much longer, since already now

Do death and strong fate stand right beside you.

But listen to me quickly, for I am here as a messenger from Zeus.

He says that the gods are angry with you, and that he

Is especially enraged of all the gods, because you are keeping

Hektor [hektor ekheis] along the curved ships in your crazy thoughts—

You do not let him go. Come now, let him go. Take payment for his corpse.”ἣ δὲ μάλ’ ἄγχ’ αὐτοῖο καθέζετο πότνια μήτηρ,

χειρί τέ μιν κατέρεξεν ἔπος τ’ ἔφατ’ ἔκ τ’ ὀνόμαζε·

τέκνον ἐμὸν τέο μέχρις ὀδυρόμενος καὶ ἀχεύων

σὴν ἔδεαι κραδίην μεμνημένος οὔτέ τι σίτου

οὔτ’ εὐνῆς; ἀγαθὸν δὲ γυναικί περ ἐν φιλότητι

μίσγεσθ’· οὐ γάρ μοι δηρὸν βέῃ, ἀλλά τοι ἤδη

ἄγχι παρέστηκεν θάνατος καὶ μοῖρα κραταιή.

ἀλλ’ ἐμέθεν ξύνες ὦκα, Διὸς δέ τοι ἄγγελός εἰμι·

σκύζεσθαι σοί φησι θεούς, ἑὲ δ’ ἔξοχα πάντων

ἀθανάτων κεχολῶσθαι, ὅτι φρεσὶ μαινομένῃσιν

῞Εκτορ’ ἔχεις παρὰ νηυσὶ κορωνίσιν οὐδ’ ἀπέλυσας.

ἀλλ’ ἄγε δὴ λῦσον, νεκροῖο δὲ δέξαι ἄποινα.

As I have mentioned in earlier posts on book 24, we find themes and motifs from book 1 echoed and closed as the epic nears its end. This speech makes a few of these moves clearer. Where book 1 has (1) Achilles get angry (using forms of kholos) after (2) a ransom has been refused to a father leading to him sending (3) Thetis as a messenger to Zeus with (4) a request/plan from Achilles, book 24 could be seen to invert it insofar as it has (1') Zeus angry over (2') Achilles not releasing/ransoming a body then (3') sending Thetis as a messenger (4') to give Achilles a plan from Zeus. But, then, this inversion flattens out to focus on the relieving of the kholos (which Thomas Walsh has argued is anger over social disorder) through the acceptance of apoina (the ransom from book 1).

Thetis’ speech also has some interesting word play that relies on etymologies. Major names in the Homeric tradition have some pretty opaque etymological origins. But folk etymologies (really any ‘false’ etymologies that are important to the reception of myths in performance) are viable objects of study both for what they tell us about Greek thoughts on language and for what they tell us about the life of myths outside our extant poems. Some of these are ridiculous–as in “lipless Achilles” or the story of an Odysseus who was born on the road in the rain. But they all tell us something about how audiences responded to traditional tales.

This speech has two points that may remind us of traditional identities before the beginning of the end of the tale. First, consider the verb/noun combination: “you are holding Hektor” (hektor ekheis). This could be a play on the meaning of Hektor’s name as “the protector” coming from a reflex of the verb ekhô (“to have, hold”) the ringing sound of Hektor ekheis may remind audiences of the irony/inversion of the man who held everything together being held prisoner, holding up the resolution of the poem by the opponent who ended his life. Second, while the speech introduction anticipates that Thetis will “name” her child, she does not, but characterizes him with a participle akheuôn, “grieving” that may remind audiences of his name’s etymology.

As Gregory Nagy has emphasized, Achilles’ name, made up of roots for “grief/woe” (akhos) and the “army/people/host” (laos) likely indicates a traditional association between the hero and pain. Some scholars have emphasized that akhos’ semantic field may also include “fear” and that his name may be important as well for his role as a lord among the dead (see Holland 1993). The major adjustment I would make here is to note yet again that we cannot know what audiences knew, but we can deduce from the internal evidence of poets like Homer and Hesiod that they were well-versed in etymological word-play and not averse to revisionist or ahistorical takes.

For me, this indicates that audiences over time (and even those in the same space) might ‘read’ Achilles’ name differently: he could be a man of sorrow, because of his own suffering; he could be one of grief, because he feels it and causes it; he could also be a cult-figure god of death, depending on what audiences knew and expected. As we can see from the Iliad, his realization in a single epic can embrace all of these identities on a continuum, as he moves from feeling akhos among/because of the people, to inspiring akhos among and across many people, to being the focal point for the experience of grief and its resolution.

One of the topics I have not written about at length in this series of posts is on the identity and the importance of the character Thetis. This omission is mostly due to my belief that nearly everything important about Thetis has already been said by Laura Slatkin in her (now classic) book The Power of Thetis. Slatkin’s book wasn’t the first of Homeric scholarship I read as an undergraduate (Richard Martin’s The Language of Heroes and Lenny Muellner’s The Meaning of Homeric EUKHOMAI Through Its Formulas have that privilege) but it is the first I ever read cover to cover without much of a pause. I took it with me on the train ride from Boston to NYC when I went on my PhD admissions interview at NYU. It changed the way I thought about the Iliad and about how to write scholarship in general. It is a sustained look at the way the Iliad integrates and toys with traditional narratives about a figure like Thetis without always acknowledging them. As a close reading of the epic, Slatkin’s book gives a glimpse into the complexity of the narrative backgrounds that make Homeric epic possible alongside an elegant demonstration of how to interpret the constant shifting ground between the story being told and the (possible) worlds it relies on.

In commenting on this passage, Slatkin summarizes “ Thetis must accept the mortal condition of Achilles, of which, as Isthmian 8 explains, she is the cause. This acceptance means the defusing of μῆνις, leaving only ἄχος. It is thus comprehensible thematically that Thetis should be the agent of Achilles’ returning the body of Hektor, of his acceptance not only of his own mortality but of the universality of the conditions of human existence as he expounds them to Priam in Book 24.” As she argues in this chapter, the Iliad in a way presupposes Thetis’ own mênis over the death and loss of her son as part of its overall thematic framework: “The Iliad is about the condition of being human and about heroic endeavor as its most encompassing expression. The Iliad insists at every opportunity on the irreducible fact of human mortality, and in order to do so it reworks traditional motifs, such as the protection motif, as described in Chapter 1. The values it asserts, its definition of heroism, emerge in the human, not the divine, sphere.” As such, I take this scene as a kind of ‘hand-off’, a turn away from the mother’s rage and the realm of the immortal, to focus ever more closely on human life.

And this is part of what Thetis does in her comments to her son. While it may seem somewhat awkward to have your mother encouraging you to have sex, there’s a symbolic sense to this. As a mother, Thetis has unique knowledge about her child’s mortality. Because she is immortal, however, this knowledge is terribly wrapped up with the anticipation that she will witness his death and live with the loss forever. One could, perhaps, see Thetis’ advice as coded for reproduction, looking to continue Achilles’ life through yet another surrogate. But I think instead there’s far more a sense of resignation and a message for all mortals. Death is inevitable, whether it comes today or forty years from now, postponing engaging in the matters of living is always a mistake.

In a rather naive paper earlier in my career, I explored the similarities in the treatment of life, death and the rhetoric of immortal fame in the Iliad and the Gilgamesh poems. One of the shared themes focused on is a turn that happens in both traditions when a woman on the margins of life gives advice to the main character to enjoy life while it lasts. Part of my inspiration for this was Thetis’ advice to Achilles and the way it seems to resonate with one variant in the Gilgamesh narrative.

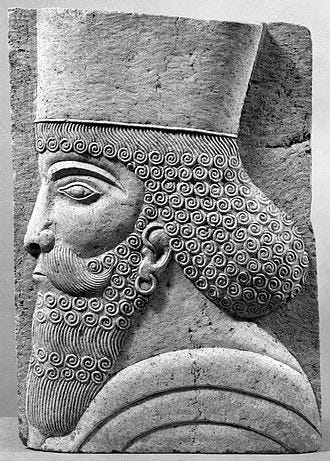

In a fragment from the Old Babylonian version of the Gilgamesh story, Gilgamesh recounts to the boatman Ur-Shanabi his experiences with Shiduri, the innkeeper. In the standard version of the story, the innkeeper/barmaid bars the door and excludes Gilgamesh. In a Tablet from Sippar, dated to the 18-17th century BCE, Shiduri listens to Gilgamesh’s lament and responds:

But you, Gilgamesh, let your belly be full,

enjoy yourself always by day and by night!

Make merry each day,

Dance and play day and night!

Let your clothes be clean,

let your hair be washed, may you bathe in water!

Gaze on the child who holds your hand,

Let your wife enjoy your repeated embrace.’ (Sippar Tablet III 6-13; Trans. George 1999, 124.)

This passage, in a way, echoes the famous epitaph attributed to Ashurbanipal in the Greek tradition, “I keep whatever I ate, the insults I made, and the joy / I took from sex”. And it has a pattern familiar to what we see in the Iliad:

1 Woman on sea/margins

2 Hears heroic lament

3 Gives advice about enjoying life (eating and sex)

The advice given about enjoying life echoes also sentiments from the biblical Enoch and Qoheleth (Ecclesiastes). In a book coming out from Yale at the end of this year, I look at these passages using frameworks from evolutionary biology to think about their possible interactions.

We could easily imagine a general diffusion of the motif throughout the eastern Mediterranean. The pattern of ideas in the heroic context makes this comparison striking. But too often our interest in comparing cultural elements like this resides in creating a kind of theoretical genealogy that establishes the originary nature of one text over another. I think it is better to start from an agnostic position regarding hierarchy and focusing instead on what we learn from differences and what we can surmise of the immediate function of narrative elements for their audiences (who are likely wholly ignorant of cultural diffusion over time).

A significant difference between the two scenes, however, is the emphasis on children in the Gilgamesh fragment. Such an acknowledgement is not absent from the Homeric epics, but it is downplayed–perhaps pointedly–in the Iliad where the loss of children and parents is repeatedly lamented. I think the similarities are due in part to(1) human mortality and our consciousness of it and (2) a trope of investing women with special knowledge about life and death. Consider, as comparison, the lyrics from John Prine’s “Spanish Pipedream” (1971). The narrative of this song presents a soldier who goes to a bar and encounters a dancer/stripper who gives repeated advice to his disenchantment:

Blow up your TV

Throw away your paper

Go to the country

Build you a home

Plant a little garden

Eat a lot of peaches

Try an’ find Jesus on your own

The chorus repeats between verses until on the third round it turns from the quoted advice into a statement of action:

We blew up our TV

Threw away our paper

Went to the country

Built us a home

Had a lot of children

Fed ’em on peaches

They all found Jesus on their own

Here, the turning away from news and the noise is a withdrawal from martial life, from the chaos of worldly events. Prine’s narrator moves on from his youthful uncertainty to a life of food, presumably sex, and caring for offspring. Each of the three examples provide advice about abandoning mourning, providing what has been called “a prescription for healing”. Now, while one might suggest that John Prine was familiar with the Old Babylonian version of Gilgamesh or Thetis’ advice in the Iliad, I would argue instead that his narrative is a reflex of ‘traditional’ advice relying on a cultural structuration of gender and an attitude towards death that is similar enough to that of the ancient eastern Mediterranean to yield themes that seem familiar.

Achilles, on the seashore, becomes a locus of shifting meaning, like so many elements in Homeric poetry. At this moment, when death stands literally and figuratively around him, his mother reminds him and us that this case is always so for mortal beings. Whether we are looking ahead for days or years, the end that comes is final and, in the words of Ashurbanipal, all we take with us is the memory of the things we did. Thetis centers this, perhaps unsettingly so, prior to the epic’s most memorable moment and the beginning of the creation of Hektor’s immortal renown through his funerary laments. Everything in book 24, this suggests, should be considered from the perspective of the life we have, always under the shadow of the death that will never leave us.

Short bibliography

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Abusch, Tzvi. 2001. “The Development and Meaning of the Epic of Gilgamesh: An Interpretive Essay.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 121 (4): 614–22.

———. 2015. Male and Female in the Epic of Gilgamesh: Encounters, Literary History, and Interpretation. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

Bachvarova, Mary R. 2016. From Hittite to Homer: The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Christensen, Joel P. 2008. “Universality or Priority? The Rhetoric of Death in the Gilgamesh Poems and the Iliad.” In Quaderni Del Dipartimento Di Scienze Dell’Antichità e Del Vicino Oriente Dell’Università Ca’ Foscari, 4, edited by E. Cingano and L. Milano, 179–202. Padova: S.A.R.G.O.N.

George, A.R. 1999. The Epic of Gilgamesh. New York: Penguin Books.

———. 2003. The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2007. “The Epic of Gilgamesh: Thoughts on Genre and Meaning.” In Gilgameš and the World of Assyria, edited by J. Azize and N. Weeks, 37–66. Leuven: Peeters.

Helle, Sophus. 2021. Gilgamesh: A New Translation of the Ancient Epic. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Higbie, Carolyn. 1995. Heroes’ Names, Homeric Identities. Ann Arbor.

Holland, G. B. 1993. "The Name of Achilles: A Revised Etymology." Glotta 71:

Hommel, H. 1980. Der Gott Achilleus. Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften 1980.1. Heidelberg: Winter.

Kanavou, Nikoletta. The Names of Homeric Heroes : Problems and Interpretations, De Gruyter, Inc., 2015

Konstantopoulos, Gina, and Sophus Helle. 2023. The Shape of Stories: Narrative Structures in Cuneiform Literature. Leiden: Brill.

Herrero de Jáuregui, Miguel. “Priam's catabasis: traces of the epic journey to Hades in Iliad 24.” TAPA, vol. 141, no. 1, 2011, pp. 37-68. Doi: 10.1353/apa.2011.0005

Nagy, G. 1979. The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

John Peradotto. Man in the Middle Voice: Name and Narration in the Odyssey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990

Pryke, Louise M. 2019. Gilgamesh. London: Routledge.

Walsh, Thomas. Feuding Words, Fighting Words: Anger in the Homeric Poems. Washington, D. C.: Center for Hellenic Studies. 2005