This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 7. Here is a link to the overview of book 6 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 7 can be split into three basic parts: an initial scene where the gods Apollo and Athena decide to orchestrate a duel; the centerpiece of the book which is duel between Hektor and Ajax; and the final third of the book which includes political assemblies among the Trojans and the Greeks that result in a brief armistice for the burial of the dead. The Achaeans, following Nestor’s guidance, use this moment as an opportunity to construct defensive barriers in front of their ships, since this is the first time in the conflict that the Trojans have pushed close enough to threaten them. The book ends with Poseidon grumbling that these new walls may become more famous and lasting than the walls he and Apollo built around the city of Troy.

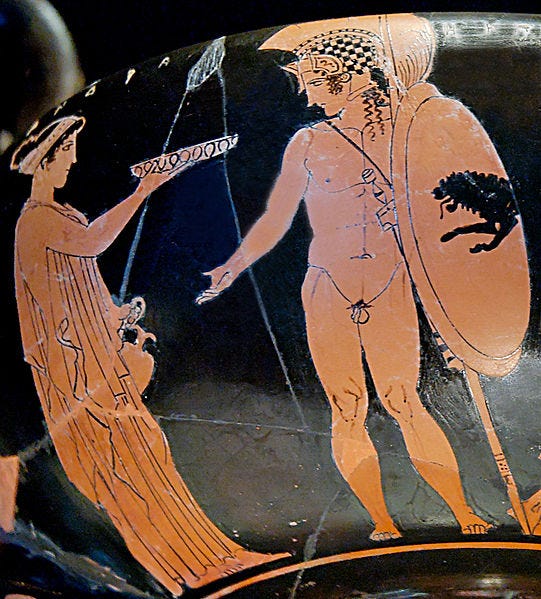

Each of the major scenes in book 7 contributes critically to some of the major themes I have noted to follow in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions. But the central themes I emphasize in reading and teaching book 5 are gods and humans, heroism, and politics. The opening conceit where the gods arrange the action of the book calls into question human decision making, agency, and free will; Hektor’s speech to challenge the Achaeans to a duel frames his few of heroic fame (kleos); and the Trojan assembly, followed by the delivery of a proposal to the Achaean assembly, provides a unique opportunity to compare Trojan and Achaean politics.

Homeric Heroes and Their Decisions

Classic debates from the 20th century about Homeric poetry from the secondary through the post-graduate level involve some variation on the relationship between fate and free will. When it comes to heroic behavior and divine intervention, this can get a bit involved: there are situations that seem somewhat clear (as when Athena pulls Achilles back by the hair in book 1 to keep him from drawing his sword and killing Agamemnon) and those that are less clear (in the same book, the narrative assertion that Hera inspired Achilles to call the assembly is not supported by any other evidence).

Evaluating these situations can be difficult for the audience external to the poem because we have nearly synoptic knowledge on what is going on. At times, we see the gods directly intervening and telling characters to do this and then the humans eventually realize they have been duped (see Athena as Deiphobos with Hektor in book 22); while in others, there are levels of obfuscation as when Zeus sends a ‘false’ dream to Agamemnon that promises him the Achaeans will be victorious on the following day, to which Agamemnon responds by ‘testing’ his army (in book 2).

Distinguishing between what the narrator reveals to us, what is revealed to internal audiences (including Homeric mortals), and what is held back helps us see that there is a lot of complexity in how and why decisions are made. Human beings are not without some agency: While everything in the Iliad may be part of Zeus’ plan, no divinity seems to cause Agamemnon to reject Chryses’ ransom and insult Achilles in book 1, even though he seems to make some claim to that effect in book 19; nor does any god inspire Achilles to ask Zeus to honor him by making the Achaeans suffer.

At a broader thematic level, then, Homeric heroes make important choices. Within the action of the epic and its interwoven plot, however, there are moments in which the gods seem more in control than others. Where Homeric characters seem ignorant of that fact, we see what scholars have called “double motivation” (or determination, or causality), following Albin Lesky. These moments offer interesting insights into Homeric views on human psychology, on theology, and on the limits of human knowledge about their own actions and motivations. On one level, we can see how human characters in the Iliad can use divine action as an excuse or explanation for their own behavior, without any clear reason for doing so. On another level, Homeric epic leaves ample room for reading different deterministic world views into the epic narrative.

I think the clearest guide for thinking about this comes from epic itself, this time the Odyssey. Near the beginning of the epic as he looks down on the mortal Aigisthus, who, despite divine advice to the contrary, has shacked up with Klytemnestra and helped murder Agamemnon, Zeus opines (Od. 1.32-34):

“Mortals! They are always blaming the gods and saying that evil comes from us when they themselves suffer pain beyond their lot because of their own recklessness.”

ὢ πόποι, οἷον δή νυ θεοὺς βροτοὶ αἰτιόωνται.

ἐξ ἡμέων γάρ φασι κάκ’ ἔμμεναι• οἱ δὲ καὶ αὐτοὶ

σφῇσιν ἀτασθαλίῃσιν ὑπὲρ μόρον ἄλγε’ ἔχουσιν

As I argue in my book on the Odyssey, I think this is a programmatic statement for the epic, inviting audiences to think about to what extent mortal decisions do impact their fate. And I don’t think this is all negative: if we can make our lives worse through our foolishness, certainly the opposite should be true, that we can ameliorate our fates through prudence.

Athena tells Apollo they should rouse Hektor to challenge one of the Achaeans to a one on one battle. The narrative information we get makes the causality somewhat clear, but not without some challenge (Il. 7.43-45).

“So he spoke, and gray-eyed Athena did not disobey.

Then the dear child of Priam, Helenos, understood in his heart

Their plan, which was really pleasing to the gods as they planned.”

῝Ως ἔφατ', οὐδ' ἀπίθησε θεὰ γλαυκῶπις ᾿Αθήνη.

τῶν δ' ῞Ελενος Πριάμοιο φίλος παῖς σύνθετο θυμῷ

βουλήν, ἥ ῥα θεοῖσιν ἐφήνδανε μητιόωσι·

A scholion explains that this means he “thought of it through his prophetic power, not because he heard their voices. (Schol, D ad Il. σύνθετο θυμῷ: ὅτι μαντικῶς συνῆκεν οὐκ ἀκούσας αὐτῶν τῆς φωνῆς. As an audience, we know that the gods thought of this, but here we see that Hektor does not know where the plan comes from and we could interpret Helenos as independently coming up with an idea that the gods considered too.

Some guiding questions for Book 7

What is the impact of the different assembly scenes (Greek vs. Trojan)?

What purpose does the duel between Ajaz and Hektor serve?

How does this book help to characterize Agamemnon and Menelaus?

A short bibliography on Homeric decision making and ‘double motivation’

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Allan, William. “Divine Justice and Cosmic Order in Early Greek Epic.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 126 (2006): 1–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30033397.

Finkelberg, Margalit (1995) “Patterns of Human Error in Homer.” JHS 115: 15-28.

Gaskin, Richard. “Do Homeric Heroes Make Real Decisions?” The Classical Quarterly 40, no. 1 (1990): 1–15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/639307.

Lesky, Albin (1961) Gottliche und Menschliche Motivation im Homerischen Epos. Winter, Universitätsverlag: Heidelberg

Andrew Porter. “Human Fault and ‘[Harmful] Delusion’ (Ἄτη) in Homer.” Phoenix 71, no. 1/2 (2017): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.7834/phoenix.71.1-2.0001.

Scodel, Ruth. "Homeric Attribution of Outcomes and Divine Causation." Syllecta Classica 29 (2018): 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1353/syl.2018.0001.

Segal, Charles. 1994. Singers, Heroes and Gods in the “Odyssey.” Ithaca.

Sharples, R. W. “‘But Why Has My Spirit Spoken with Me Thus?’: Homeric Decision-Making.” Greece & Rome 30, no. 1 (1983): 1–7. http://www.jstor.org/stable/642739.

Teffeteller, Annette. “Homeric Excuses.” The Classical Quarterly 53, no. 1 (2003): 15–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3556479.

Additional bibliography for book 7

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know. Follow-up posts will address kleos and Trojan politics

Castiglioni, Barbara. “Menelaus in the « Iliad » and in the « Odyssey »: the anti-hero of πένθος.” Commentaria Classica, vol. 7, 2020, pp. 219-232.

Christensen, Joel P.. “Trojan politics and the assemblies of Iliad 7.” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, vol. 55, no. 1, 2015, pp. 25-51.

Davies, M.. “Nestor's advice in Iliad 7.” Eranos, vol. LXXXIV, 1986, pp. 69-75.

Duban, J. M.. “Les duels majeurs de l'Iliade et le langage d'Hector.” Les Études Classiques, vol. XLIX, 1981, pp. 97-124.

Finglass, Patrick J.. “The ending of Iliad 7.” Philologus, vol. 150, no. 2, 2006, pp. 187-197.

Finkelberg, Margalit. “The sources of Iliad 7.” Colby Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 2, 2002, pp. 151-161.

Kullmann, Wolfgang. “Gods and Men in the Iliad and the Odyssey.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 89 (1985): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/311265.

Maitland, Judith. “Poseidon, Walls, and Narrative Complexity in the Homeric Iliad.” The Classical Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 1, 1999, pp. 1–13. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/639485. Accessed 17 Nov. 2023.

Roisman, Hanna M. “Nestor the Good Counsellor.” The Classical Quarterly 55, no. 1 (2005): 17–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3556237.

Strauss Clay, Jenny. “Homer’s epigraph: Iliad 7. 87-91.” Philologus, vol. 160, no. 2, 2016, pp. 185-196.

Trapp, Richard L. “Ajax in the ‘Iliad.’” The Classical Journal 56, no. 6 (1961): 271–75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3294852.