A few weeks ago, when I first announced the the plan for this substack, I declared I would soon start providing a post per book of the Iliad per week after first providing a series of posts about reading and teaching epic including one on the polyphonic nature of Homeric poetry, another providing tools for engaging with the Greek itself, one providing some background to the so-called “Homeric Problem[s]”, and then, finally one that provides eight concrete pieces of advice for reading the Iliad, One subject untouched–and which I may leave unaddressed–is the relationship between history and Homeric poetry. This is a personal preference for me, since I see the Homeric epics as mostly a fantasy of the past from which questions about the historicity of the Trojan War are primarily distractions. [See below for some resources on this topic].

Anyone who knows me would be unsurprised that I set out to start talking about the Iliad and took rather long to get to the point. Once, probably in 2003 or so, my wife asked me to tell her what the epic was about. After 45 minutes or so, she interrupted me and asked me what point of the poem I was talking about. She was somewhat unamused that I had not yet finished book 1.

Anyone who knows the Iliad well should not find this surprising. The epic is filled with action; but even the ‘simple’ scenes are full of associated meanings, replete with potential resonances, and deeper meanings based on what one knows (or think they know). On top of this there are thousands of years of interpretive traditions and engagements that are labyrinthine enough to make Reddit seem linear.

So, one of the things I find to be useful when teaching Homer or guiding people through the Iliad is to focus on a handful of themes. By nature of both the structure of the poem and the character of its plot, the Iliad presents a series of interwoven themes that ebb and flow as the epic progresses to its end. To return to the musical composition analogy I use in another post, I think it is helpful to imagine certain melodies or movements introduced early in the epic and reintroduced for new meaning and contrast as the plot moves us from one notional position to another. The repetition here is far from simple iteration: each return to familiar language and ideas is a repetition with difference: the audience and the characters are changed by the events that unfold, and the combination and reintroduction of themes in the changing contexts has a complicating if not generative effect.

I hope to highlight activations of these themes in posts on each book, but before I start on that project, I want to summarize them and anticipate their major movements. As a note, there are sub-themes I consider more like contributing motifs (e.g. ransom, xenia, mourning) or imagery (e.g. water, fire, laughter); and some of the themes I emphasize may be better posed as subordinate in some way. I think readers and teachers are free to identify and explore other themes as well. The five themes I like to emphasize are (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans); (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions. I will give brief introductions to each in this post and follow up with additional references when I focus on these themes in subsequent posts.

Politics

“Really, may I be called both a coward and a nobody

If I yield every fact to you, whatever thing you ask”ἦ γάρ κεν δειλός τε καὶ οὐτιδανὸς καλεοίμην

εἰ δὴ σοὶ πᾶν ἔργον ὑπείξομαι ὅττί κεν εἴπῃς· Homer, Iliad 1

As everyone knows from the beginning of the Iliad, the epic is not about the Trojan War, it is a story set within it. It is, according to its own proem, a tale of how Achilles’ rage brought ruin on his own people. The Iliad is intensely political in that it asks questions about where authority should come from, who should wield it, how they should wield it, and what the consequences of dysfunctional politics may be. The primary ‘melody’ in this movement is of the conflict between Agamemnon and Achilles, but this reverberates through questions of how the war is prosecuted by the Greeks, how they maintain their coalition, and how their experimental polity compares to the governance of Olympos and and the politics of the city of Troy.

There has been a lot written about the political conflicts among the Greeks but much less on Trojan politics and even less on divine political arrangements. I have argued more than once that to really get into the political questions of the Iliad, we need to understand that the epic explores politics on three separate stages (the Greeks, Trojans, and Gods) that are both comparative and contrastive. The major political treatments of the Greeks occur in books 1, 2, 4, 9, 19, and 23. (People often miss that the Funeral Games of Patroclus are an attempt by Achilles to explore different allocations of goods and power). Trojan politics are really emphasized in books 2 (briefly in the catalogue of ships), in the contrast of assemblies in book 7, in the depiction of Hektor in books 6, 8, 12, 13, 18, 22 (especially in his engagement with Polydamas). The politics of the Gods are explored in assemblies/exchanges in books 1, 4, 8, 15, 16, and 24.

Heroism

“Homer made Achilles the best man of those who went to Troy, Nestor the wisest, and Odysseus the most shifty.”

φημὶ γὰρ Ὅμηρον πεποιηκέναι ἄριστον μὲν ἄνδρα Ἀχιλλέα τῶν εἰς Τροίαν ἀφικομένων, σοφώτατον δὲ Νέστορα, πολυτροπώτατον δὲ Ὀδυσσέα. Plato, Hippias Minor

“May I not die without a fight and without glory but after doing something big for men to come to hear about”

ὴ μὰν ἀσπουδί γε καὶ ἀκλειῶς ἀπολοίμην, ἀλλὰ μέγα ῥέξας τι καὶ ἐσσομένοισι πυθέσθαι. Homer, Iliad 7 [Hektor speaking]

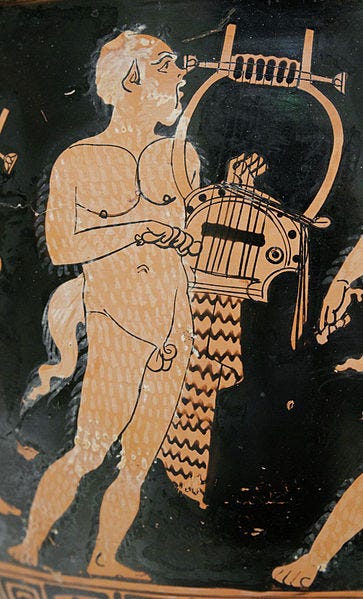

It is really hard to talk about the Homeric epics without talking about “heroism”. I start by explaining to students that, rather than evoking notions of virtue and self-sacrifice, in epic poetry a “hero” can mean three things: (1) a person in their full bloom of strength (in accord with the etymology shared with the name Hera); (2) a member of the generation before ours, the race of Heroes as described in Hesiod’s Works and Days; or (3) a figure who follows a narrative pattern of withdrawal and return (see Oedipus, Perseus, etc. Note, I am not using the language Campbell’s Hero’s Journey.). Homeric heroes, as Erwin Cook describes them, are not savior figures, but are instead figures who suffer and cause suffering. These three ideas are oversimplifications as well: there is a religious/cult aspect to heroes outside the worlds of the poems, explored well by scholars like Greg Nagy.

I think that the Iliad emphasize that heroes are dangerous to communities and that the Iliad and Odyssey together work in concert to provide an etiology for the destruction of the race of heroes, a justification for their absence from our world, and an exploration of how we value human beings across sub-themes like words/deeds, community/individuals, destruction/construction, mortality and immortality, etc. There is almost no book of the Iliad that doesn’t address heroism in some way, but the chief ones follow Achilles and Hektor with some interludes treating characters like Aeneas (5 and 22), Sarpedon (12 and 16), or Lykaon (21). For Achilles and Hektor, see especially Books 1, 6, 9, 11, 16, 22, and 24

Gods and Humans

“Whenever the poet turns his gaze to divine nature, then he holds human affairs in contempt.”

ὅταν δὲ ἀποβλέψῃ εἰς τὴν θείαν φύσιν ὁ ποιητής, τότε τὰ ἀνθρώπινα πράγματα ἐξευτελίζει Scholion to Homer

As Barbara Graziosi and Johannes Haubold argue in their book Homer: The Resonance of Epic, the Homeric epics are part of a sequence with Hesiodic poetry that traces “cosmic history” from the foundation of the universe to the lives of archaic Greek audience. Part of this movement in Homer is to establish metaphysical ‘baselines’, the differences between gods and human beings, and what to expect from the human lives. The Iliad helps to explain why the worlds of gods and humans should be more separate, explores the relationship between divine will and human agency, and also provides a backdrop for the shared beliefs and customs of the Greeks that we might call ‘religion’ today.

The depiction of the gods can be difficult because they are at once characters in the narrative and reflections of actual Greek beliefs. Ancient and modern critics have been troubled by the less-than-positive depiction of the gods (Xenophanes and Heraclitus famously complained about it). But the general literary view is that the gods provide the framework for underscoring the importance of human behavior. Gods can misbehave, they can cheat, and lie and commit adultery because they are immortal. They don’t face the same level of consequences that human beings do because they have virtually limitless opportunities to screw up and try again. In line with the theme of heroism, the treatment of mortality and immortality in the Iliad helps audiences to understand that human lives have meaning because they are limited.

Interactions between the gods and humans happen throughout the epics, but some of the most critical moments are when the gods intervene in human actions or reflect on them in Books 1, 4, 8, 15, 16, 23, 24. Of chief importance among these are the speeches of Zeus, the discussion about the death of Sarpedon, and the final divine assembly in book 24 that (re-)establishes the primacy of burial and mourning rites.

Family & Friends

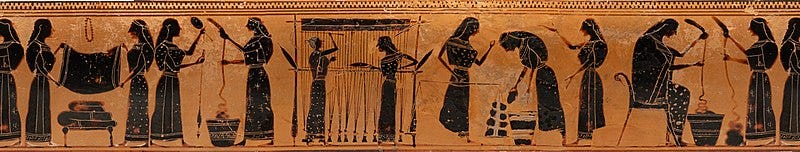

Throughout the themes I have already discussed, the sub-theme or motif of violence is dominant. Indeed, one way of thinking about the Iliad is that it is a prolonged invitation to think about war and when to fight. The answer I think it gives is that we should fight to defend the people we love and for little else. Sub-themes within this are women and children in Homer and the relationship between Achilles and Patroklos. Indeed, just as violence could be its own theme, so too could the treatment and experience of women in Homeric epic. I generally discuss these topics as a group because they orbit around Homeric treatments of heroes, politics, and violence. The place of friends and enslaved women is central to the political questions of book 1, but we see them both especially in the depiction of Trojan families. Book 6 is a powerful opportunity to think about life during wartime for non-combatants, as are the laments of books 18 and 24.

Narrative Traditions

One of the topics I have long been most interested in is how Homeric epic relates to other narrative traditions. (This is the motivating question at the core of the book I wrote with Elton Barker, Homer’s Thebes). I provide an overview of some of these issues in my post on Centaurs, but I think the question of how Homeric epic appropriates from and responds to other mythical narratives is key to understanding its composition, the date of its composition, and its eventual pre-eminence. A simple place to start is with the stories Homeric heroes tell (the paradeigmata), but there are moments of engagement with other traditions in nearly every line of Homeric epic. How we think about these engagements–whether they are allusions, intertexts, or something else–are important questions in current Homeric scholarship that also reflect how we think about the making of meaning and storytelling in general. One of the things I really like to emphasize is that the Iliad seems very conscious not just of other story traditions but of its own status as a story to be used as a (counter-)model for their lives.

Some resources for thinking about Homer and History.

There are some good sources that give us a start on the Homeric epics’ relationship with history. I like the multiple perspectives provided by the edited volume Archaeology and the Homeric Epics,. Readers will find some disagreement in major scholarly approaches, but most counsel caution: see Kurt Raaflaub’s article “Homer, the Trojan War, and History,” Trevor Bryce’s “The Trojan War: Is there Truth Behind the Legend,” Susan Sherratt’s “The Trojan War: History or Bricolage?”, Korfmann’s, Latacz’s and Hawkins’ “Was There a Trojan War?”