This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 10. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

As I have implied in the last two posts, confusion about whether or not Iliad 10 is an essential part of the epic is rooted in part to different concepts of textuality, fixity, and unity. The primary issues scholars have with book 10 are (1) we have a scholion saying it is “Homer’s” but not “part of the Iliad, (2) the action of the book does not advance the main part of the story; and (3) the events of the book are not mentioned in other books. To this, we can add (4) West’s insistence that “Nothing suggests that the story of the night foray and the killing of Rhesos had any traditional basis. Rhesos achieves nothing at Troy and therefore has no place in the war.”

Each of these points relies in some way on core assumptions about what the Iliad is. Qualm 4 posits that a story requires traditional basis to be part of our Iliad. This is not at all true of a lot of the Iliad and patently absurd in the face of our limited evidence. The Iliad is best where it capitalizes on a tension between what people think they know about the Trojan War and what happens in the poem. For issue #3: there are also many, many parts of the epic that are not mentioned anywhere else in the poem. For #1, well, ancient scholiasts say lots of things: perhaps Iliad 10 was not a well-known and common part of the Iliad as some audiences knew it: but it has been around and part of our poem long enough that Alexandrian scholars framed it as a Peisistratean interpolation. All of our texts of the Iliad went through some kind of an Athenian ‘recension’!

The only substantial argument I can see is #2, that the book does not advance the main part of the story. This is an entirely subjective statement, supposing that there is a main story to advance and, further, that “advancing the story” is the chief purpose of any book of the epic. As I discuss in an earlier post, I think that book 10 does important work in creating suspense after book 9 and the embassy to Achilles; in addition, Dolon himself offers some interesting echoes of Achilles.

Thinking about those echoes has made me reflect again on exactly how book 10 “advances” the poem. It is not necessarily about the action—since the death of Dolon, Rhesos, and the loss of those marvelous horses does not change the balance of the war at all. But the actions do advance the plot of the epic.

Let me address this by starting from the first line of the poem: Μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω ᾿Αχιλῆος. “Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles.” I think we are so familiar with this opening that we forget it could have gone another way. Imagine knowing about Achilles as a man of rage, a demigod with superhuman strength and overflowing emotions. In art, he appears poised in a game with his cousin, killing Penthesileia, ambushing Troilos, abusing Hektor’s body. His rage may have been primarily known as a reaction to the death of Patroklos (in the Iliad) or over Antilokhos (in the lost Aethiopis). The opening line could have introduced any number of a range of stories.

Here’s a translation of the proem that goes through it line by line:

Goddess, sing the rage of Achilles, the son of Peleus,

The ruinous [rage] which made countless griefs for the Achaeans

And sent many stout souls to Hades

And made the heroes’ bodies pickings for the dogs

And all the birds, while Zeus’ plan was being fulfilled,

From the time indeed when those two first stood apart in conflict

The son of Atreus, lord of men, and shining Achilles.

Note how new details are added with each line. We don’t actually hear who suffers from Achilles’ rage until halfway through the second line. Audiences hearing this version of the story of Achilles’ rage may not have been shocked at its focus, but they certainly would have been clued in to the fact that this song is not necessarily about the death of a friend. This is a poem about Achilles’ anger against his own people and the deaths he causes among them. It becomes about his friend’s death because Achilles causes it.

So let’s go back to book 10. Or, let’s start a little earlier: book 8 ends a day of fighting with the trojans camping outside their city for the first time in the war. This act prompts Agamemnon to suggest going home, but results in political assembly and council to send the embassy to Achilles. This action and the embassy itself is a product of a political consensus, of group activity. When Achilles refuses, the group does not fracture. The main players—Diomedes, Nestor, Odysseus, and Agamemnon—maintain the Achaean coalition despite Achilles’ absence.

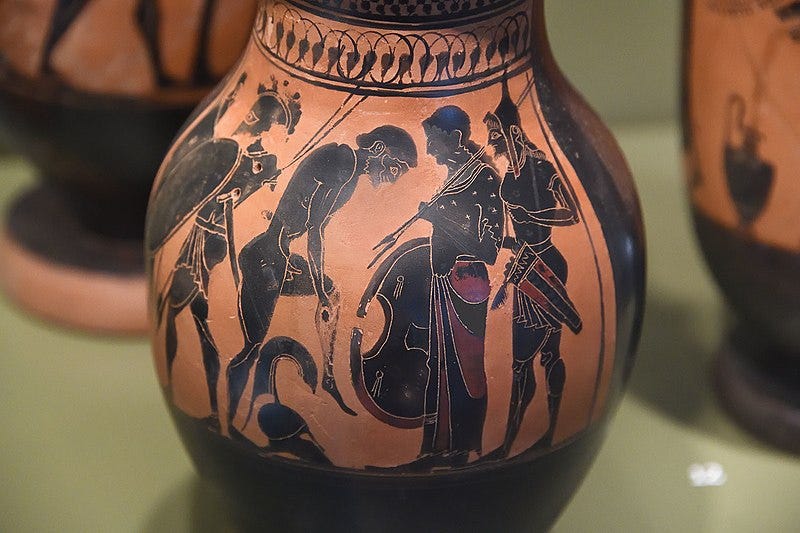

Book 10 continues this long night and the action of book 9. Everyone else goes to sleep, but Agamemnon stays away, stressed about what he’s going to do. He tosses, looking from the Trojan fires to the ships, and calls Nestor to make a plan to protect the Greeks. Nestor gathers the captains together and suggests reconnaissance to see if the Trojans are really going to stay outside the walls. He offers a small prize and the promise of glory in exchange, after describing the task. Diomedes volunteers: a bunch of others do too, but Diomedes picks Odysseus.

Contrast this with what happens on the Trojan side: Hektor is depicted as keeping the Trojans awake at night, calling the best of them together, and then starting with a promise of pay, a “big gift”: the best horses among the Achaeans. Hektor does this without support from a council; Dolon goes forward alone, without help, wholly motivated by the promise of the prize he will receive in return.

These scenes contrast in the way that the assemblies of book 7 do: they show a more collective-focused, collaborative leadership for the Achaean than the authoritarian, limited politics of the Trojans. In this case, in particular, the outcomes of the actions matter as much as the characterization. Dolon’s isolation and vulnerability contrasts with Diomedes and Odysseus.

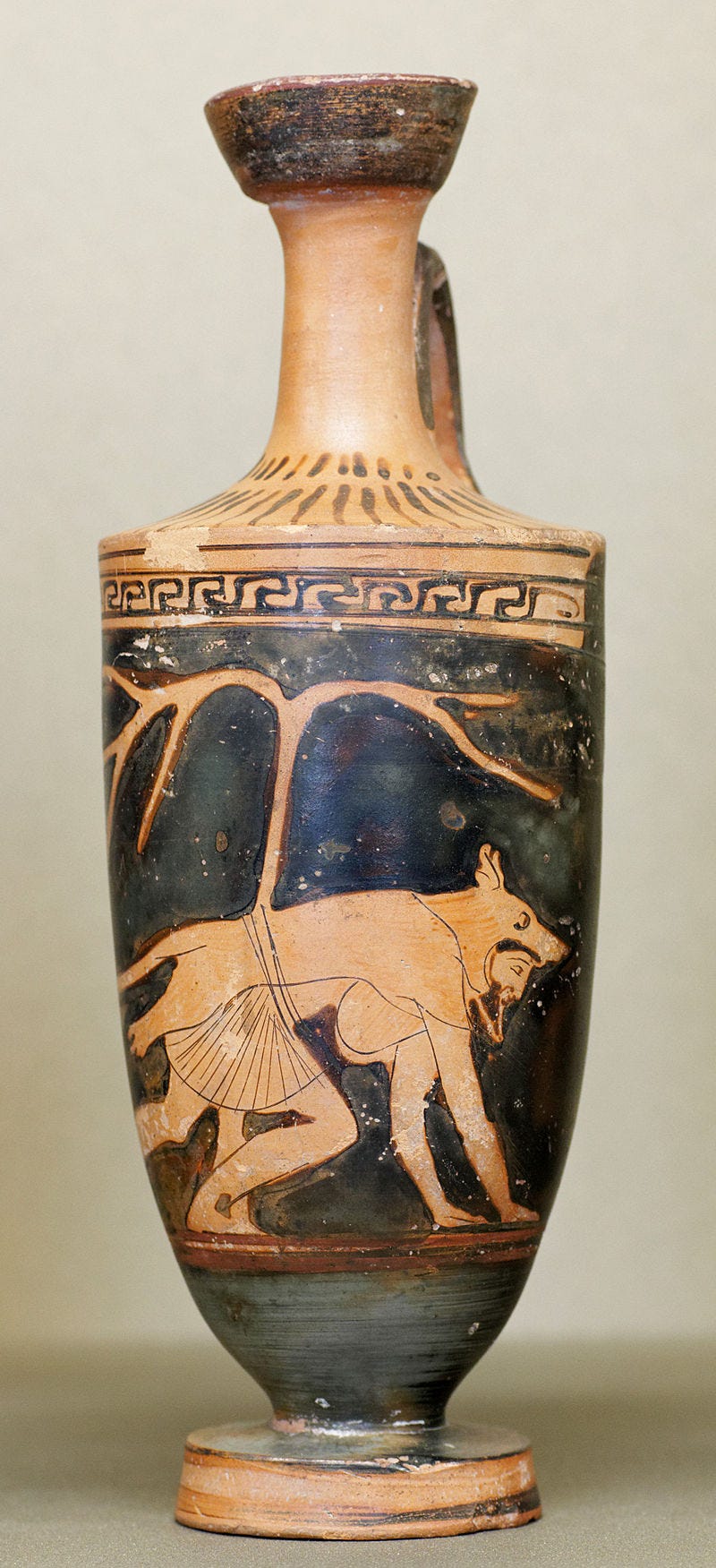

And his ‘swift feet’ but “wicked form” (ὃς δή τοι εἶδος μὲν ἔην κακός, ἀλλὰ ποδώκης) may just be a subtle commentary on Achilles, who stands alone during book 10 while his people face the danger he put them in. As a method of ‘advancing the Iliad,” this certainly engages critically with the epic’s themes of politics and heroism. I think it may also engage with the “rage of Achilles” as well. As Lenny Muellner, my first Greek teacher, argues in his book The Anger of Achilles that mênis is a sanctioning response against the violation of cosmic order—and for Achilles it separates him from friendship, from friends. Dolon’s echoing of Achilles may thus be far from accidental: book 10 provides another opportunity to reflect on the importance of communities and friendship.

Like Achilles, Dolon stands alone. Unlike Achilles, he meets a quick death, because, while he may be swift-footed, but he’s far from divine. And the point of book 10 is in part thinking through these contrasts.

Bibliography on book 10 and the Doloneia

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Davidson, Olga Merck. “Dolon and Rhesus in the ‘Iliad.’” Quaderni Urbinati Di Cultura Classica 1 (1979): 61–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/20538562.

Dué, Casey, and Mary Ebbott. 2010. Iliad 10 and the Poetics of Ambush: A Multitext Edition with Essays and Commentary. Hellenic Studies Series 39. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Fenik, B. 1964. Iliad X and the Rhesus: The Myth. Collection Latomus 73. Brussels.

Haft, Adele J. “‘The City-Sacker Odysseus’ in Iliad 2 and 10.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 120 (1990): 37–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/283977.

Sheldon, Rose Mary. “THE ILL-FATED TROJAN SPY.” American Intelligence Journal 9, no. 3 (1988): 18–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44325966.

Stagakis, George. “DOLON, ODYSSEUS AND DIOMEDES IN THE ‘DOLONEIA.’” Rheinisches Museum Für Philologie 130, no. 3/4 (1987): 193–204. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41233632.

STEINER, D. “‘Wolf’s Justice’: The Iliadic Doloneia and the Semiotics of Wolves.” Classical Antiquity 34, no. 2 (2015): 335–69. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26362659.

West. M.L. 2011. The Making of the Iliad: Disquisition and Analytical Commentary. Oxford.