This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 10. Here is a link to the overview of book 9 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 10 (also called the “Doloneia”) takes into the Achaean and Trojan camps at night after the embassy to Achilles. Both sides are worried about what the other might do, so they send out volunteers to spy. Diomedes and Odysseus meet the Trojan Dolon during their scouting and force him to reveal information about the Trojan troop positions before they kill him. They slaughter some Trojan allies in their sleep and steal their horses. The plot of this book engages critically with the major themes I have noted to follow in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions, but the central themes I emphasize in reading and teaching book 9 are politics, heroism, and narrative traditions.

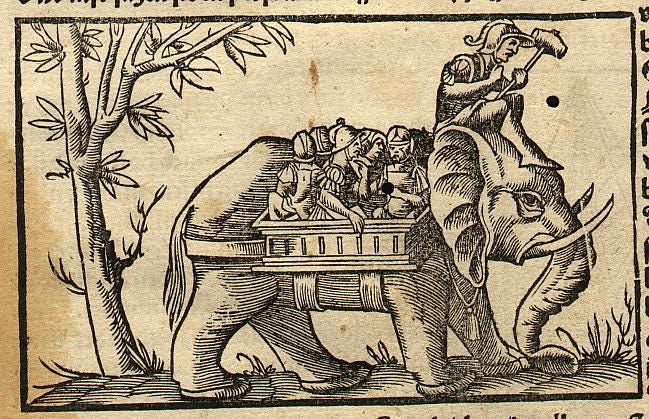

Among all other topics, I find the political contrast between the ‘volunteers’ on both sides to be telling; and I also think there is a lot to say about differences in characterization between the Homeric Hektor in this book and his appearance in the Rhesus attributed to Euripides. But before we can even begin to consider those topics, there is a massive war elephant in the room.

Is Book 10 Homeric?

Schol. T Ad Hom. Il. 10b 1 ex

“People say that this book was privately composed by Homer and was not part of the Iliad, but that it was added to the poem by Peisistratos.”

ex.(?) φασὶ τὴν ῥαψῳδίαν ὑφ' ῾Ομήρου ἰδίᾳ τετάχθαι καὶ μὴ εἶναι μέρος τῆς ᾿Ιλιάδος, ὑπὸ δὲ Πεισιστράτου τετάχθαι εἰς τὴν ποίησιν.

Walter Leaf, in his commentary on the Iliad quotes this scholion and cites two common reasons that ‘modern’ scholars have accepted the ancient commentary as gospel because the action does not advance the main story and the contents of the book are not mentioned elsewhere in the epic. The ancient scholar, however, does not insist that the book does not belong to ‘Homer’, but instead is a separate story, added by Peisistratos during the so-called Athenian recension.

Martin West in The Making of the Iliad, writes “It is the almost unanimous (and certainly correct) view of modern scholars that this rhapsody is an insertion in Il. by a different poet. The conclusion is based on several considerations:” He later adds: “Nothing suggests that the story of the night foray and the killing of Rhesos had any traditional basis. Rhesos achieves nothing at Troy and therefore has no place in the war.”

These conclusions—from the ancient scholars through to the modern day—betray essential assumptions about what a complete poem is and willfully (in the case of West) dismiss a model of composition that admits change in the performance tradition. Andrew Ford, in his review of West’s 2011 book, marks this dismissal as a disagreement or difference:

“West’s ultimate objective is the text made by that unus maximusque poeta who must stand— nihil ex nihilo fit —as the source of the Iliad. It is easy enough to point out that this corresponds to no empirical reality but is West’s abstraction from the data; but this is only to say that, like any interpreter, West must construct the text as he construes it. Nagy’s ultimate concern, equally ideal, is the Tradition, the ever-evolving medium that generated (in a Chomskyan sense) Homeric poetry.5 Hence the difference between them is not simply whether “Homer” wrote but what textualization means. West insists that once the oral versions of the Iliad were written down, the usual processes of textual transmission took over, calling for traditional philological approaches. In Nagy’s sweeping vision, transcription itself is part of the tradition and variation in the written sources is the continuing operation of the system of oral poetics. For Nagy, this system is what needs representing and is best represented as a multi-text. A consequence of this broad view is that P’s poem must be recognized as an “authentic” multiform by an undoubted master of the style (call him W if you like), though Nagy would deny it (and any version) originary status.”

I don’t know how much there is for me to add to this conversation, except that even West concedes the antiquity of both Book 10 and its inclusion in all major manuscripts from antiquity. I think Casey Dué and Mary Ebbott have pretty much made the best case for the traditionality of the Iliad 10 in their Iliad 10 and the Poetics of Ambush: A Multitext Edition with Essays and Commentary. (If you have time, read it: it lays out a detailed view of ‘texts’ in a multiform system and counters well arguments about the propriety of the ambush (it is perfectly ‘heroic’!), the traditionality of the figures (Rhesos is super traditional, Dolon, less so; but for the Iliad and our evidence, what does that really mean), and the utility of taking a multitext approach (do it, it is useful).

Gimmick Episodes and Narrative Contexts

I want to offer another avenue of support, drawing on the basic proposition of the scholion, that “the Doloneia is Homer’s, but someone else added it to this poem.” Part of what I have been suggesting in my re-read of the Iliad—and, indeed, in my teaching over the years—is that we need to distinguish between different ways of experiencing Greek epic for ancient audiences. Ancient audiences rarely read the epic in its entirety and prior to the 4th century BCE, I suspect most still enjoyed epic in performance. The opportunities for monumental performances—those that presented the ‘whole’ story—would have been rare. The majority of epic performances would likely have been based on episodes. Any major festival performance, like those we reconstruct for the Panathenaia (the major Athenian festival) would have invited maximalist versions of the Iliad or the Odyssey. I think monumental efforts to transcribe and transmit the epic would have been similar.

So part of my interest in looking at Book 10 is what it does: it is, in a way, a classic “side quest”, what some might call a gimmick episode or a theme episode, as in Angel’s “Smile Time”, when everyone gets turned into a puppet or Buffy’s “Once More with Feeling”, one of a group of wonderful musical episodes in fantasy/scifi television. As a viewer I adore these episodes, even though they rarely contribute to the overall plot arc. They allow show creators to experiment with different forms and ideas and they let audience members luxuriate in the extension of the fantasy world. I think there’s a very real connection between fan fiction and engagement with popular narrative and the “throw away” episodes that take us all off the clock. We get to linger a bit in the world slightly turned upside down, yet still in the knowledge that we will return to the story, eventually.

Something I have written about a few times is the tension in our drive to get to the end of a narrative and our desire for a story to never really end. Gimmick episodes expand the boundaries of a tale and temporality feed that latter desire. One of the things that has only recently occurred to me is how much the context for the reception of a story conditions how permeable the narrative boundaries are. A recent tweet sent me into a reverie.

I spent a fair amount of time in graduate school not reading Homer or doing school work but instead either binging DVD seasons of shows like Buffy, Angel, The Wire while also impatiently waiting for the next episode of The Sopranos or Battlestar Galactica. The arc-driven drama of the later seasons of Buffy or every season of The Wire made side-quest episodes useful: they relieve some of the stress of the narrative lurching forward (I am staring at you, LOST) while they also create suspense and anticipation at the delay of the major tale. Modern television, post streaming, is designed for a different pace: for binge watching and money saving. Major shows have gone from 22 episodes to 12 to 8 (and even fewer). And when we cut away the ‘fat’, we lose the ability to linger in the tale, to explore its world more broadly, to luxuriate in the fictions we create together. Instead, we are driven almost mercilessly towards the conclusion of the plot and the question we all end up asking: what do we watch next!?

If this analogy has value for Homer, I think it is in thinking about that tension between the whole story and the enjoyment of the parts. When we used to enjoy long form narrative television an hour a week, separated by conversation, speculation, surprises, and anticipation, we had more time for a narrative lark, be it a miscue or a standalone piece that allowed for expansion and experimentation. The episodes of the Iliad, I think, reflect that kind of archipelago mapping: distinct miniature narratives, held together by the single journey we take through them.

The Doloneia (book 10) maintains the same characters, advances some essential Iliadic plots, and contributes to the whole by (1) allowing some downtime after the intensity of book 9, (2) suspending the resumption of the action, and (3) allowing us to see characters who aren’t Achilles engaging with each other and the field of battle in surprising ways. It may not be all about the rage of Achilles, but book 10 makes us feel the impact of his rage all the more.

Some Reading Questions for Book 10

What are the motivations for night raids from either side?

What are some of the implications of the characterization and then the treatment of Dolon?

How is Iliad 10 consonant with the themes of the rest of the Epic?

Bibliography on book 10 and the Doloneia

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Davidson, Olga Merck. “Dolon and Rhesus in the ‘Iliad.’” Quaderni Urbinati Di Cultura Classica 1 (1979): 61–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/20538562.

Dué, Casey, and Mary Ebbott. 2010. Iliad 10 and the Poetics of Ambush: A Multitext Edition with Essays and Commentary. Hellenic Studies Series 39. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Fenik, B. 1964. Iliad X and the Rhesus: The Myth. Collection Latomus 73. Brussels.

Gaunt, D. M. “The Change of Plan in the ‘Doloneia.’” Greece & Rome 18, no. 2 (1971): 191–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/642655.

Haft, Adele J. “‘The City-Sacker Odysseus’ in Iliad 2 and 10.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 120 (1990): 37–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/283977.

Sheldon, Rose Mary. “THE ILL-FATED TROJAN SPY.” American Intelligence Journal 9, no. 3 (1988): 18–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44325966.

Stagakis, George. “DOLON, ODYSSEUS AND DIOMEDES IN THE ‘DOLONEIA.’” Rheinisches Museum Für Philologie 130, no. 3/4 (1987): 193–204. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41233632.

STEINER, D. “‘Wolf’s Justice’: The Iliadic Doloneia and the Semiotics of Wolves.” Classical Antiquity 34, no. 2 (2015): 335–69. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26362659.

West. M.L. 2011. The Making of the Iliad: Disquisition and Analytical Commentary. Oxford.

WEST, MARTIN. “The Homeric Question Today.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 155, no. 4 (2011): 383–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23208780.

A lot of this seems to be about heritability of both wealth and forms of wealth, and personal characteristics. Dolon's dad is a herald, someone who conveys information between unconnected parties, which is what Dolon proposes to do. A herald also brokers deals, as Nestor and Odysseus have just tried to do in book 9 and as Dolon is now trying to do on his own behalf. Dolon's being an only son with 5 sisters implies that femininity is a thing his father passes on.

There's also a counterpoint about wealth between 9 and 10. Agamemnon is clearly rich beyond belief given the payoff he offers Achilles, but the wealth is in well built towns and their associated sheep and cattle, as well as gold and tripods and horses and Lesbian women, whereas Dolon has merely much gold and much bronze. There's a parallel here with old money/new money snobbery in the US and UK. Rich dukes and founding fathers good, nouveaux riches bad.

And thank you for the scholiast on the correlation between wealth and horse breeding. Compare the microphilotimios in Theophrastus Characters 21 who goes to the agora "forgetting" that he is still wearing his spurs.