This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 2. Here is a link to the overview of book 1 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

The second book of the Iliad can be split into three basic sections: the so-called diapeira (Agamemnon’s testing of the troops); the assembly speeches following the rush to the ships in response to the ‘test’ (the protest of Thersites, followed by the speeches of Odysseus and Nestor); and the Catalogue of Ships). Each of these scenes contributes critically to the some of the major themes I have noted to follow in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions.. But the central themes I emphasize in reading and teaching book 2 are politics and narrative traditions.

The first half of book 2 essentially addresses the political problems set into play in book 1: Agamemnon tests his men to see if they are still dedicated to the mission and they run away. Thersites appears to channel some of Achilles’ dissent from book 1 and to act as a scapegoat for that political fracture. When he is literally beaten out of the assembly by Odysseus, it opens up space for Odysseus and Nestor in turn to refocus their efforts, reemphasize their collective goals, and reconstruct Agamemnon’s authority. (Disclosure, I have written on Agamemnon’s test and the debates around it and have some opinions.) I have included a bibliography on Thersites below. I will provide a later post about Agamemnon’s so-called test.

The result of this series of events is clear if you trace the similes of in book 2: the Achaeans start compared to images of clashing and conflict and end up compared to unified forces of nature directed against a common goal. This resolves in part some of the political tension in book 1, but does not address Achilles’ absence fully. The actions of the Achaean assembly are sufficient to return the coalition to war with a unified front, but insufficient to winning there. As part of the larger political theme, this helps to illustrate that the political resilience of the Achaeans, despite their bloody internecine conflict, resides in the multiple leaders who work together.

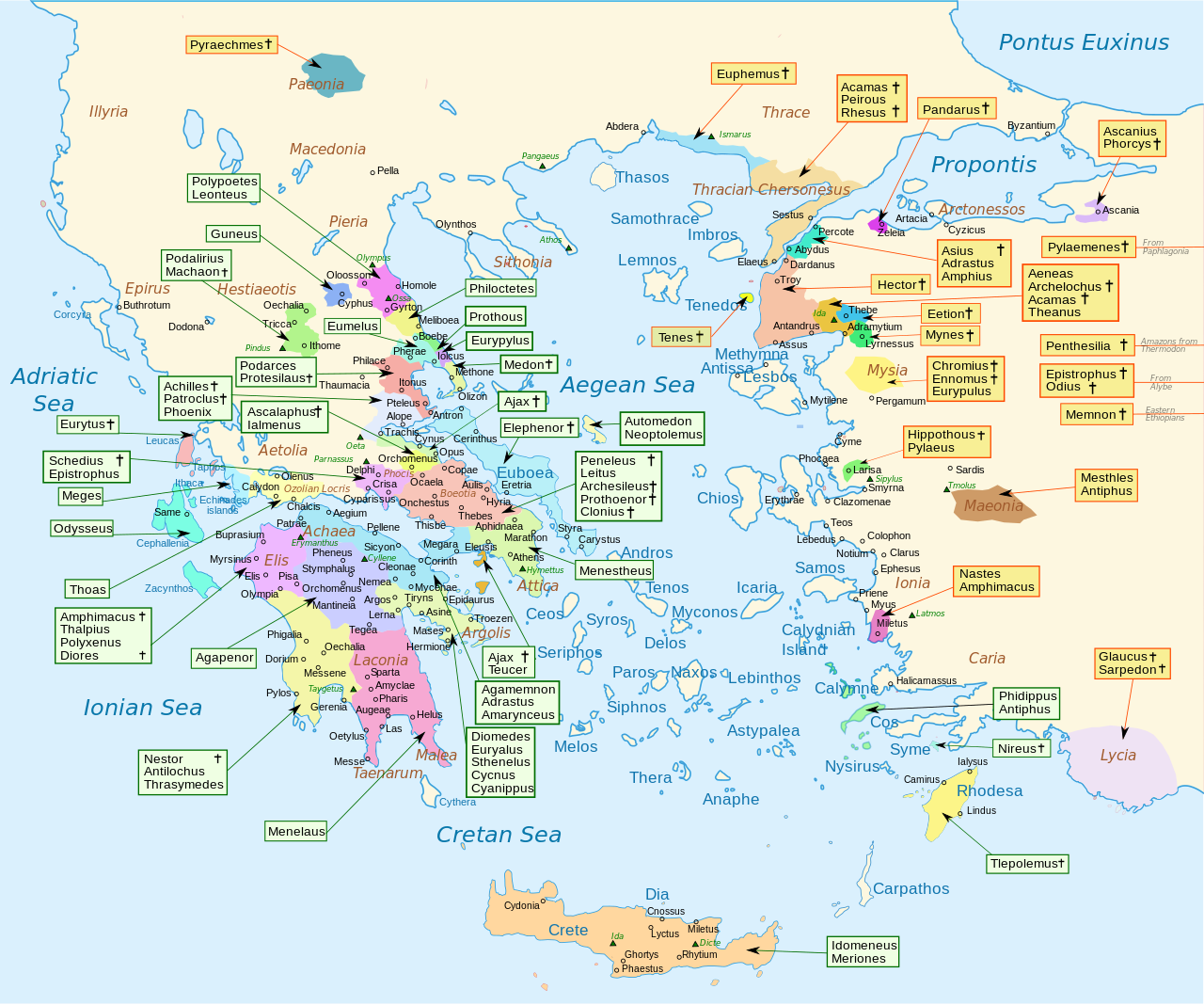

The unity at the end of the assemblies translates in part to a throwback to the beginning of the war in the performance of the Catalogue of Ships. Strictly speaking, a catalogue of all the participants in the war begins in a very different narrative, not recited nine years after its beginning. I suspect that the Catalogue was a popular motif in antiquity and was integrated into our Iliad both as a recognition of this and as a reflection of its audiences geographical knowledge and political realities. I think this interactive map of the catalogue is really fascinating and worth playing around with. Here’s a list of all the contingents with some links

In addition to being a fascinating reflection on the interaction between mythical space and the lived geography of antiquity, the catalogue is also evidence of how our Homeric epic engages with other versions of its own story and the larger Trojan War narrative in general. The catalogue clearly predates the action of the epic–figures like Philoktetes are listed as being elsewhere or dead (Protesilaos)–and the contents help us to understand the political dynamics: as Nestor puts it in book 1, Agamemnon is powerful politically because he rules over more people.

But the catalogue is also a lesson in how epic narrative works. Every figure is a potential story, a genealogy or a tragedy waiting to be unveiled. At the same time, the catalogue is an opportunity to silence other traditions by leaving them unmentioned, something Elton Barker and I examine in Homer’s Thebes.

Previous generations of scholars might have bracketed the catalogue as being imported from another poem or tradition. I think its position in this book following the reconstitution of the experimental Achaean polity is a brilliant ‘literary’ response to the particular challenge of creating an authoritative Trojan War poem. It makes sense to have a retrospective overview of the war at this point: The test itself raises the question of the stakes of the war; Odysseus and Nestor remind us of its beginning and the anticipated length; and the catalogue itself returns us from the theme of Achaean politics to the war in general. The inclusion of ‘traditional’ material both appropriates other narratives and instrumentalizes them. In effect, the larger mythical storyscape becomes a footnote to the story being told. And the catalogue is re-tunes the audience for the confrontation with the Trojans in book 3. In addition, this use of narrative material extraneous to the timeline of this particular plot also sets the audience up for even more surprising ‘flashbacks’: a duel between Paris and Menelaos (after 9 years!) and Helen’s description of the Greek heroes from the walls of Troy (the so-called Teikhoskopia).

Often left out of discussions of the Catalogue are the Trojans, who get their own list at 2.816-877. As Eunice Kim has recently argued, there is an art and message to this section that helps us to understand Hektor and the Trojans in general. So, make sure you read it to the end! Hilary Mackie’s book Talking Trojan, also has a nice treatment of this section and Benjamin Sammons’ The Art and Rhetoric of the Homeric Catalogue provides a great overview and fine bibliography on this type of poetry in general.

Book 2 touches upon other themes as well. Zeus’ intervention to send Agamemnon a false dream at the beginning of book 2 engages with questions about his “plan” as well as notions of human will and divine fate (so, Gods & Humans) and the inset heroic narratives of the catalogue provide many different ways to think about local heroes and larger traditions (Heroism).

Some guiding questions

What does the Diapeira do and how does it respond to the conflict of Iliad 1?

How do we understand Thersites’ dissent and its treatment?

How would you characterize Nestor and Odysseus in this book?

What are the impact(s) of the catalogue of ships?

Bibliography on Thersites

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

BARKER, ELTON. “ACHILLES’ LAST STAND: INSTITUTIONALISING DISSENT IN HOMER’S ‘ILIAD.’” Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society, no. 50 (2004): 92–120. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44696692.

Brockliss, W. 2019. “Out of the Mix: (Dis)ability, Intimacy, and the Homeric Poems.” Classical World 113: 1–27.

Christensen, J. (2021). Beautiful Bodies, Beautiful Minds: Some Applications of Disability Studies to Homer. Classical World 114(4), 365-393. https://doi.org/10.1353/clw.2021.0020.

Robert Kimbrough. “The Problem of Thersites.” The Modern Language Review 59, no. 2 (1964): 173–76.

Lowry, E. R. 1991 Thersites: A Study in Comic Shame.

Marks, Jim. 2005. “The Ongoing Neikos: Thersites, Odysseus, and Achilleus.” AJP 126:1–31.

Postlethwaite, N. “Thersites in the Iliad.” Greece & Rome 35: 83-95.

Rockwell, Kiffin. “THERSITES.” The Classical Outlook 56, no. 1 (1978): 6–6. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43933965.

Rose, M. L. 2003. The Staff of Oedipus: transforming disability in ancient Greece. Ann Arbor.

ROSE, PETER W. “THERSITES AND THE PLURAL VOICES OF HOMER.” Arethusa 21, no. 1 (1988): 5–25.

Rosen, R. M. 2003. “The Death of Thersites and the Sympotic Performance of Iambic Mock-ery.” Pallas 61:21–136.

Stuurman, Siep. “The Voice of Thersites: Reflections on the Origins of the Idea of Equality.” Journal of the History of Ideas 65, no. 2 (2004): 171–89. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3654205.

Thalmann, W. G. 1988. “Thersites: comedy, scapegoats and heroic ideology in the Iliad.” TAPA 118:1-28.

Thomson, R. G.. 1997. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. New York.

Williams, B. 1993. Shame and Necessity. Berkeley and Los Angeles