This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 22. Here is a link to the overview of Iliad 21 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 22 has three basic parts, creating suspense before the final face-off between Achilles and Hektor; the faceoff itself followed by the mistreatment of Hektor’s body; and the first responses to Hektor’s death, culminating in Andromache’s first lament. In the first part, Hektor ignores pleas from his parents to return to the city and speaks to himself; the second part presents a famous and somewhat confusing (in terms of motivation) duel between Hektor and Achilles; and the third features some of the most emotional speeches in the epic.

Each of these narrative concerns adds something to the themes I have outlined in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions. Among these, however, I think book 22 speaks most directly to heroism, gods and humans, and friends and family.

All of the segments in book 22 are deeply interdependent. Understanding Hektor’s behavior may be one of the most important interpretive challenges in approaching book 22. A simile before he speaks may help us start.

Homer, Iliad 22.93-98

“As a serpent awaits a man in front of its home on the mountain,

One who dined on ruinous plants [pharmaka], and a dread anger overtakes him

As it coils back and glares terribly before his home.

So Hektor in his unquenchable [asbestos] fury [menos] would not retreat,

After he leaned his shining shield on the wall’s edge.

He really glowered as he spoke to his own proud heartὡς δὲ δράκων ἐπὶ χειῇ ὀρέστερος ἄνδρα μένῃσι

βεβρωκὼς κακὰ φάρμακ᾽, ἔδυ δέ τέ μιν χόλος αἰνός,

σμερδαλέον δὲ δέδορκεν ἑλισσόμενος περὶ χειῇ:

ὣς Ἕκτωρ ἄσβεστον ἔχων μένος οὐχ ὑπεχώρει

πύργῳ ἔπι προὔχοντι φαεινὴν ἀσπίδ᾽ ἐρείσας:

ὀχθήσας δ᾽ ἄρα εἶπε πρὸς ὃν μεγαλήτορα θυμόν

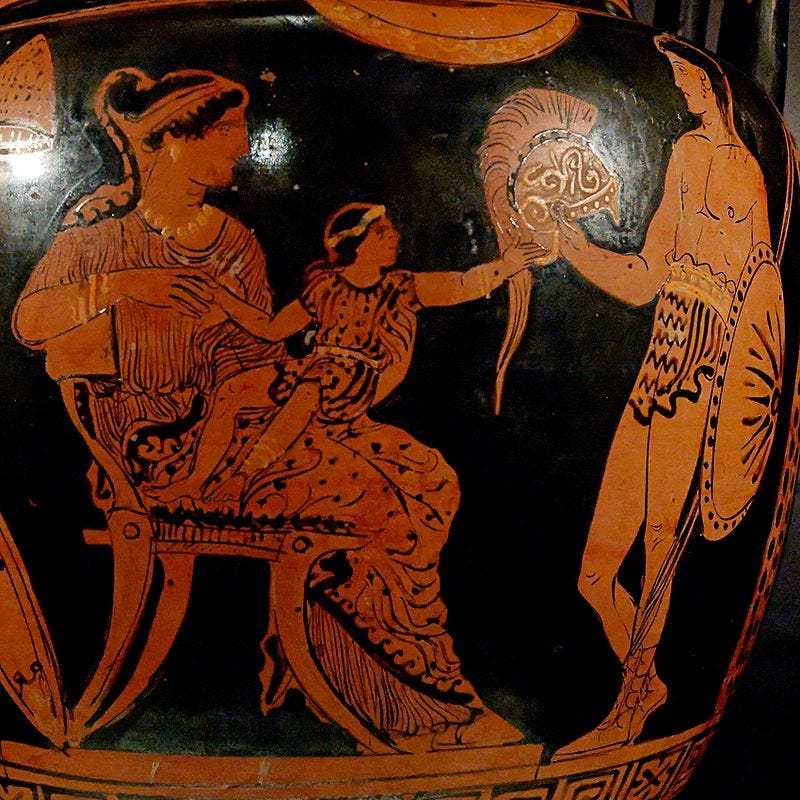

As he stands before the walls of his city in book 22, Hektor is compared to a snake, coiled to strike an intruder. This moment of anticipation of violence is prolonged as Hektor turns away from the pleas of his family not to face Achilles. In a moment marked by the repeated speech introduction “ (ὀχθήσας δ᾽ ἄρα εἶπε πρὸς ὃν μεγαλήτορα θυμόν), Hektor ruminates, and worries despite what the opening simile anticipates. He resolves to face Achilles, but then immediately changes his mind: “When Hektor noticed Achilles, a tremor overtook him and he could not bear to wait for him / but he left the gates behind and left in flight” Ἕκτορα δ᾽, ὡς ἐνόησεν, ἕλε τρόμος: οὐδ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ἔτ᾽ ἔτλη / αὖθι μένειν, ὀπίσω δὲ πύλας λίπε, βῆ δὲ φοβηθείς).

What happens between the end of Hektor’s speech and his choice to run from Achilles? Very few people who read or write about the Iliad can make great sense of Hektor. His traditional character is part of James Redfield’s widely cited The Tragedy of Hektor (1975) and his strange engagement with his advisor Polydamas–with whom he argues on three separate occasions–is seen as a function of the limits of Trojan politics but rarely as evidence of the emotional response of an actual human being.

Indeed, throughout the Iliad, Hektor’s behavior can be hard to parse, and so much harder to defend. He is harsh to his brother, but within limits; his kindness to Helen and joy in his son seems ill-fit to his rejection of Andromache’s advice. In war, he seems relentless, speaking repeatedly of glory and the alternating chance of war, while pursuing an offensive onslaught that seems either wholly irrational or an artificial hastening of the war’s ultimate plot. Sure, we see the man-killing Hektor in all his unquenchable fury, but there are questions: he barely fights Ajax to a draw in book 7; he needs the help of another man and a god to slay Patroklos in book 16; he must be tricked to face Achilles when the final conflict awaits him.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I started to think of Hektor as someone marked by prolonged uncertainty and torturous anticipation. In a way, we have lived in our own kind of siege over the past year: often unable to leave our homes, afraid of what days and weeks would bring, and plagued beyond all else by uncertainties that undermined many things we held to be true, even sacred. I started to think of Hektor and the Trojans as living this way not for one year, but for nine, hearing of the deaths or abductions of family members in other cities, seeing no way to break out. Before the beginning of the epic we know, Hektor spent nine years pacing the walls of his city, unable to fight off his enemies yet unable to flee. Until, of course, the Iliad’s action lets him break free.

Fight, Flight, or Freeze

In the third edition of his The Body Bears the Burden: Trauma, Dissociation, and Disease (2014), Robert Scaer looks at the cycle of arousal and rest that characterizes the function of our nervous system in response to crisis or danger. In simple terms, we can think of the fight or flight response which triggers different neurotransmitters to prepare for rapid response: in a resting state, our bodies are prepared for and more efficient at digesting and storing nutrients and also at processing and storing knowledge of facts and events (13). The fight/flight response puts us in a high-energy nervous state, raising blood-pressure and moving blood into our muscular system.

Such a shifting of biological resources is an essential survival tool. But when we experience prolonged arousal without release or resolution we can become locked in or frozen, establishing an unstable state that may look immobile but may actually be “rapid and exaggerated sympathetic/parasympathetic oscillation (15). To put it in other words: when we face a crisis situation we can neither fight nor flee, our “freeze” reaction is a parafunctional cycling through the same fight/flight and resting process over and over again. In this state, our minds can become “numb and dissociated” and our vascular and digestive systems suffer.

As Scaer outlines (15-16), Animals often show remarkable responses to this freeze (a “discharge”) that can include convulsions and more in an instinctive attempt to restore “autonomic homeostasis” (16), that is, stability. Human beings, however, rarely show such ‘rests’ to discharge the trauma and reset the body. Such an inability to resolve the freeze moment, it seems, compounds the long term dangers of physical responses to trauma and the likelihood that memories of the events will incite similar physical responses, a return to a traumatized state. Scaer argues that many chronic diseases may be rooted in the reshaping of our brains by trauma and the inability of our conscious minds to distinguish between now and traumatizing events.

Reading Hektor’s Trauma

When we see Hektor before the walls of Troy, he is “coiled” like a snake (elissomenos) and he wouldn’t retreat because of his unquenchable heart. Note that I translate that participle clause ἄσβεστον ἔχων μένος causally. This is, of course, a significant choice, but I think a well-motivated one. This is the only time in Greek epic when menos—one’s energy, life force—is described as asbestos, “inextinguishable, unsatisfiable”. The adjective appears to mark extreme or powerful expressions of emotion as in describing the laughter of the gods at Hephaistos (1.599) or war cries of groups as they engage in battle (11.500, 11.530; 13.169; 13.450; 16.267). In the Odyssey, asbeston twice modifies kleos (4.584; 7.133). This word seems to describe extreme moments of pitch, or aggression with a sense of duration. But as Lorenzo Garcia argues in his Homeric Durability, asbestos marks things that ultimately cannot endure: what the sound of a laugh or a war-cry share in common with Hektor’s menos is an unsustainable intensity. In addition, the adjective marks something that is public, shared, or heard by others. Here, the asbeston menos is something private, a massive, unsustainable thing somehow contained within a single person.

The simile compares Hektor to an animal coiled for attack; in describing his refusal to retreat, the narrative uniquely describes the energy driving him; the speech introduction that follows places him in a motif of deliberation over fighting or fleeing. Speeches introduced by the formula “He really glowered as he spoke to his own proud heart” (ὀχθήσας δ᾽ ἄρα εἶπε πρὸς ὃν μεγαλήτορα θυμόν) are dramatic representations of deliberation—moments that happen in an instant but are unfolded in the time of performance to allow audiences to consider the inner workings of heroic minds. The simile of the serpent creates extra space and invites audiences to consider the space between the image of the coiled snake and Hektor’s actions: it is as much about how Hektor is the snake and how he is not.

For mortals, the moment of deliberation seems to be that very freeze before the selection of fight or flight: at 11.404-410, Odysseus, caught alone in battle worries about being overcome as the battle rages around him. At 17.90, Menelaos pauses in the defense of Patroklos’ body, afraid to face Hektor alone. At 18.5, Achilles is paralyzed by fear that something has happened to Patroklos and later at 20.143, Achilles finds himself perplexed at the sudden disappearance of Aeneas who has been rescued by the gods. At 21.552, Agenor the son of Antenor pauses mid-battle to decide to run or face Achilles.

The participle characterizing the speech, okhthêsas, moreover, expresses anger or resentment and may be an iterative of ekhthomai, that same root that gives us Greek words for hostility and enmity. Especially when combined with the asseverative particle ἄρα, this verb communicates an inward wrath at a choice with no good options. It is the coiling of anticipation, of loss, and of a loss of control. It is, I think, a formulaic marker for the process of navigating between fight and flight. In its pairing with the opening simile, it marks Hektor in that same moment, in an extended freeze. His resolution, however, contrasts with the other scenes: Hektor ends up acting contrary to his choice to stand.

Hektor’s menos, his anger, is a reflex of his loss of control and of his longing for something to be different. Andromache anticipates this when she speaks to him in book (6.407-409):

“Divine one, your menos will destroy you and you do not pity

Your infant child and my wretched fate, the one who will soon

Be your widow. For the Achaeans are on their way to kill you…”δαιμόνιε φθίσει σε τὸ σὸν μένος, οὐδ’ ἐλεαίρεις

παῖδά τε νηπίαχον καὶ ἔμ’ ἄμμορον, ἣ τάχα χήρη

σεῦ ἔσομαι· τάχα γάρ σε κατακτανέουσιν ᾿Αχαιοὶ

Hektor’s drive to protect those he cares for most is the very thing that separates him from them, that unites them only in loss and longing. This calls to my mind the work of my friend, Emily Austin, who has written a book foregrounding the thematic importance of loss and longing (pothos) in the Iliad: it is the sudden absence that motivates Achilles’ menis. I think it is also the unconquerable fire that keeps Hektor from ever truly being still.

Thinking about the fight/flight/freeze complex as described by Scaer helps us confirm the poetic function of a Homeric formula: it also serves to invite audiences into a mind navigating a moment of crisis, of choice or judgment (hence Greek krisis) over running away or facing danger. In combination with a striking simile and a strange description of Hektor’s menos, this pattern also helps us see what can happen when the deliberation fails, when the freeze prolongs. Hektor’s menos is overloaded, it is too thoroughly interiorized, coiled inside him, breaking him from within.

Hektor, Fighting and Fleeing

Almost 15 years ago, Elton Barker and I wrote an article about debates over fight or flight in the New Archilochus Poem and Homer. In it, we argued that both Homer and Archilochus were engaged in a tradition of poetic debate about the merits of fight or flight, transcending our narrow concepts of genre and operating ahierarchically, that is, prioritizing neither Homer nor Archilochus, but providing evidence of debate and reflection over time. I don’t think we’re wrong, still; but I do think that this debate is about more than drama and poets: it is about representing human emotion and cognition.

Broadly speaking, Scaer’s framework and my own experience makes me think that we need to rethink Hektor’s behavior throughout the epic and the depiction of Trojan responses to the war in general, allowing more richness to the emotive and cognitive content. There are thematic ties that tell a story of their own.

When Hektor speaks to Andromache in book 6, he anticipates the shame he worries about in book 22 and considers his wife’s suffering after his death. He expresses a characteristic fatalism when he dismisses Andromache to her weaving, saying, “I claim that there is no one who has escaped his fate, / whether a good person or a bad one, after they are born” (μοῖραν δ’ οὔ τινά φημι πεφυγμένον ἔμμεναι ἀνδρῶν, /οὐ κακὸν οὐδὲ μὲν ἐσθλόν, ἐπὴν τὰ πρῶτα γένηται, 6.488-489).

Perhaps it is too much to read into this passage to say that Hektor thinks flight is impossible (he does…), but it certainly helps explain his subsequent actions: keeping the Trojan army out on the field at night in book 8, breaking through the Greek fortifications despite a bad omen in book 12, and refusing to return to the defense of the city in book 18. When Polydamas calls for them to retreat, Hektor continues to insist Zeus is on their side and declares, “I will not flee him from the ill-sounding battle, but I will stand / against Achilles either to win great strength or to be taken myself. War is common ground and the one who kills is killed” (…οὔ μιν ἔγωγε / φεύξομαι ἐκ πολέμοιο δυσηχέος, ἀλλὰ μάλ’ ἄντην /στήσομαι, ἤ κε φέρῃσι μέγα κράτος, ἦ κε φεροίμην / ξυνὸς ᾿Ενυάλιος, καί τε κτανέοντα κατέκτα, 18.306-309).

When Hektor freezes in the choice to fight or flee in book 22, he knows there is no other option. In his speech, he often surprises modern audiences with a wish that he and Achilles could exchange pledges like young lovers and wishes neither would have to die even as he admits that shame would prevent him from retreat. It is as if Hektor has a handful of cards and is repeatedly flipping through them, looking for one that will change a fate he knows cannot be changed. He goes back through his own stories, perhaps stopping at his conversation with Andromache and thinking about what he loses, what he needs, and the absence of choices remaining to him. At the end, he returns to that deceptive idea, that fate alternates and he just might win the day (εἴδομεν ὁπποτέρῳ κεν Ὀλύμπιος εὖχος ὀρέξῃ, 130).

The Trojans in Trauma

Of course, there’s not a single way to think about this moment. David Morris in his 2015 The Evil Hours notes that Freud theorized that war neuroses came from an internal conflict between self preservation and responsibility to honor and comrades (15). As Jonathan Shay adds in his Achilles in Vietnam, trauma undermines “the cohesion of consciousness” (1995,188). And this fragmentation has been born out by neurobiological studies since.

The additional thing to think about for Hektor and for us, is that the impact of trauma can be increased by duration. What if we think of the Trojan leader as coiled for nine years, as representing a people besieged, constantly poised between the need to fight and the desire for an impossible flight. The repeated suppression of the fight or flight choice, the prolonged freeze would be traumatizing neurobiologically. It would change the way Hektor’s mind and body worked.

I do want to be careful to say that I am not saying the Greeks would have seen it this way precisely, but rather that there is clearly a traditional marker through the collocation of simile, deliberative introduction, and the invitation to the audience to linger with Hektor for a moment (the freeze) that modern observers have seen as having both psychological and neurobiological components. Ancient audiences would have seen their own peers shaped and reshaped by similar traumas and their poems show evidence of understanding the long term impact experiences like isolation, betrayal, and helplessness can have on the working of human minds (think of Philoktetes, Ajax, Odysseus, and others like Klytemnestra and Medea in tragedy).

So, this is not a positivistic reading saying “this thing is definitely that” but more that our modern scientific discourse has outlined a space of behavior that traditional poetics found meaningful too and that the correlation between these observations may help us understand something about Hektor others have missed. But I think this is bigger than Hektor: it may be about the Trojans, a people besieged, as a whole.

In the traditional story of the Trojan War, the story of the horse seems all but ridiculous (ok, it is ridiculous). But what if we considered the Trojan willingness to accept a clear trap, to engage in such extreme denial, as a function of their collective trauma? We are no strangers to large parts of our population refusing to accept what others see as fact, in engaging in clearly self-destructive behavior because it adheres so much more closely to what they want to be true and reality causes them so much pain.

In Greek myth, trouble tends to run in families and cities, traveling from father to son and grandson until the whole line is used up. This too resounds with what we have learned over the past century. We know trauma can be passed down three generations. Large-scale studies of oppressed populations show greater evidence of trauma related behaviors (depression, suicide, drug use) in the grand-children of those who suffered abuse and displacement than their peers. And these responses may be about more than the power of discourse and socialization. There’s growing evidence for the reshaping of DNA as a result of trauma. Our ancestors’ experiences may impact those parts of our DNA that inform our mental health and shape our responses to traumatic events in our lives.

Trauma impacts our physical health; it impedes learning and new memories; it alters how we respond to crisis; untreated, it deprives us of even instinctual advantages. The Iliad’s story of the Trojan War gives its audiences traumatized warriors and families on both sides. It shows people fraying then unraveling under the pressures of long term conflict. And it provides us with vignettes of men and women trying to make sense of the world as everything they know breaks down. When Hektor tries to face his death, but then runs, the traditional language and its images unfold a human mind at its most intense moment of crisis.

Over the past few years, I have often found myself arguing about what the humanities are, about what they are good for. A poem like the Iliad is not some timeless relic, a perfect object to be worshipped for the unmixed good it can bring. But it is a deeply complex inheritance, a poem that gives us the opportunity to move between what we know and see now and what others experienced thousands of years ago. By tracing out the story of Hektor’s mind and his body’s burden, we may find just a little help in learning how to carry our own.

Short bibliography on Hektor

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know. Follow-up posts will address kleos and Trojan politics

Clark, Matthew. “Poulydamas and Hektor.” College Literature 34, no. 2 (2007): 85–106. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25115422.

Combellack, Frederick M. “Homer and Hector.” The American Journal of Philology 65, no. 3 (1944): 209–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/291490.

Farron, S. “THE CHARACTER OF HECTOR IN THE ‘ILIAD.’” Acta Classica 21 (1978): 39–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24591547.

Horn, Fabian. “The psychology of aggression: Achilles’ wrath and Hector’s flight in Iliad 22.131-7.” Hermes, vol. 146, no. 3, 2018, pp. 277-289. Doi: 10.25162/hermes-2018-0023

Lynn Kozak, Experiencing Hektor: Character in the Iliad. Bloomsbury Classical Studies Monographs. London; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. xiv, 307.

Hillary Mackie. Talking Trojan: Speech and Community in the Iliad . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1996.

Van der Mije, Sebastiaan Reinier. “Bad herbs: the snake simile in Iliad 22.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 64, no. 3, 2011, pp. 359-382. Doi: 10.1163/156852511X505079

W. R. Nethercut. “Hektor at the Abyss.” Classical Bulletin 49 (1972) 7-9.

Oele, Marjolein. “Priam’s despair and courage: an Aristotelian reading of fear, hope, and suffering in Homer’s « Iliad ».” Logoi and muthoi : further essays in Greek philosophy and literature. Ed. Wians, William. SUNY Series in Ancient Greek Philosophy. Albany (N. Y.): State University of New York Pr., 2019. 297-317.

Pantelia, Maria C. “Helen and the Last Song for Hector.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 132, no. 1/2 (2002): 21–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20054056.

Pucci, Pietro. “Divine protagonists in the « Iliad »: Hector’s death in book 22.” Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic, vol. 1, 2017, pp. 175-205.

Ready, Jonathan L.. “Iliad 22.123-128 and the erotics of supplication.” The Classical Bulletin, vol. 81, no. 2, 2005, pp. 145-164.

James Redfield. Nature and Culture in the Iliad: The Tragedy of Hektor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975.

Scott, John A. “The Parting of Hector and Andromache.” The Classical Journal 9, no. 6 (1914): 274–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3287165.

Scott, John A. “Paris and Hector in Tradition and in Homer.” Classical Philology 8, no. 2 (1913): 160–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/262449.

Traill, David A. “Unfair to Hector?” Classical Philology 85, no. 4 (1990): 299–303. http://www.jstor.org/stable/269583.