This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 10. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

As I write about in my first post on book 10, the so-called Doloneia has given interpreters fits (why is it there at all?), but I think there are very, very good reasons to consider it part of the whole. One structural reason I argue there, is that it provides a rest and a bit of anticipation of what will come when the fighting begins again. I think there are also important thematic and compositional reasons to consider it an integral part of the Iliad.

In their commentary on book 10 of the Iliad, Casey Dué and Mary Ebbott do a great job of teasing out the meaning available from each phrase. As they discuss in their introduction, the character of Dolon, who appears as the Trojan spy in book 10, is not well-established in the tradition. Part of the way we know that is that he is introduced with a somewhat enigmatic, but detailed passage. Homeric speech introductions can be formulaic—in a way, they are a kind of type scene signaling what kind of speech should be expected. But within the regular patterns, we find room for new, even strange information. When I teach Homer, I tell students to pay particular attention to introductions because they bring in surprising yet almost always relevant information.

In television we have the concept of a ‘red-shirt’, a character from Star Trek who appears and dies shortly after being introduced. Some of them are like NPCs (non-player characters) with barely a name, but others receive longer stories, narratives that engage with the larger story in a way. Dolon’s introduction is a good example of a kind of Homeric redshirt (but he probably deserves some description that rates him a little higher than such disposable characters). And his introduction also helps us think about Homeric composition. In particular it illustrates how characterization within a speech can be anticipated by the introduction.

Hom. Iliad 10.314-317

“There was among the Trojans a certain son of Eumedes,

The divine herald, a man all about gold, all about bronze, Dolon.

He was pretty base in form, but fleet-footed,

But he was the only son after five sisters.

Then he spoke among the Trojans and to Hektor.

Hektor my heart and proud spirit urges me

To go near the shift ships and learn from them.

But come, raise your scepter to me and swear to me

That you will give the horses and the chariot decorated with bronze,

Those things that usually carry the blameless son of Peleus.

I won’t be a useless spy nor unaccomplished.

I will go straight into the army until I come

To Agamemnon’s ship where I bet that the best men

Are taking counsel over their plans whether they will leave or fight.”ἦν δέ τις ἐν Τρώεσσι Δόλων Εὐμήδεος υἱὸς

κήρυκος θείοιο πολύχρυσος πολύχαλκος,

ὃς δή τοι εἶδος μὲν ἔην κακός, ἀλλὰ ποδώκης·

αὐτὰρ ὃ μοῦνος ἔην μετὰ πέντε κασιγνήτῃσιν.

ὅς ῥα τότε Τρωσίν τε καὶ ῞Εκτορι μῦθον ἔειπεν·

῞Εκτορ ἔμ’ ὀτρύνει κραδίη καὶ θυμὸς ἀγήνωρ

νηῶν ὠκυπόρων σχεδὸν ἐλθέμεν ἔκ τε πυθέσθαι.

ἀλλ’ ἄγε μοι τὸ σκῆπτρον ἀνάσχεο, καί μοι ὄμοσσον

ἦ μὲν τοὺς ἵππους τε καὶ ἅρματα ποικίλα χαλκῷ

δωσέμεν, οἳ φορέουσιν ἀμύμονα Πηλεΐωνα,

σοὶ δ’ ἐγὼ οὐχ ἅλιος σκοπὸς ἔσσομαι οὐδ’ ἀπὸ δόξης·

τόφρα γὰρ ἐς στρατὸν εἶμι διαμπερὲς ὄφρ’ ἂν ἵκωμαι

νῆ’ ᾿Αγαμεμνονέην, ὅθι που μέλλουσιν ἄριστοι

βουλὰς βουλεύειν ἢ φευγέμεν ἠὲ μάχεσθαι.

The line of introduction itself (ἦν δέ τις ἐν Τρώεσσι Δόλων Εὐμήδεος υἱὸς) has a bit of a meandering suddenness to it: as West notes in his commentary (2011) the opening is “the means for introducing a new character. A scholiast confirms this and then explains the details prefigure what he will do in the text.

Schol. ad Hom. bT ad Il. 10.314 ex 1-3

“There’s a need for some description to explain what is unknown about the man. Nonetheless, he is the kind of person who lusts after Achilles’ horses and turns out to be a turncoat in a little bit.”

διηγήσεως ἐδέησε πρὸς τὸ σημᾶναι τὸ ἄδηλον τοῦ ἀνδρός. ὅμως τοιοῦτος ὢν τῶν ᾿Αχιλλέως ἵππων ἐρᾷ καὶ μετ' ὀλίγον προδότης γίνεται.

There are three themes in this passage: the first is Dolon’s appearance (he is ugly but fast), the second is his relationship to wealth (he likes it!), and the fourth is his status as a single son with five sisters. One scholiast quips that he has so much cash because of the dowries of his sisters! West (again, 2011) suggests that this detail is important because it increases his value in a potential ransom (Cf. Dué and Ebbott: Certainly Dolon’s wealth comes into play after his capture: when he promises Diomedes and Odysseus a great ransom (10.378–381) the traditional characteristic of his wealth indicates that he could indeed pay handsomely in exchange for his life.” As Dué and Ebbott also note, the patronymic here is an indication of some kind of traditional character.

Ancient scholars draw interesting connections between Dolon’s wealth and his interest in Achilles’ horses:

Schol T. ad Hom. Il. 10.315b ex

“All about gold”: This is because he loves gold. Or because of some other boasting he performed for gold. For being wealthy also creates a longing for the raising of horses

πολύχρυσος: καὶ ὅμως ἠράσθη κέρδους. ἢ δι' ἀλαζονείαν ἕτερόν τι παρὰ χρυσόν· τὸ γὰρ πλουτεῖν καὶ ἱπποτροφίας ἐμ-ποιεῖ πόθον.

But his appearance and his wealth are also related to his sisters and his efficacy in war:

“This shows that he is unmanly because he was raised in wealth.”

ἵνα καὶ ὡς ἐν πλούτῳ τεθραμμένος ἄνανδρος ᾖ,

Schol. In Hom. Il. 10.317b

“Because he is terribly like a woman and reckless”

ὡς γυναικοτραφὴς δειλὸς ἦν καὶ ῥιψοκίνδυνος.

Schol T. ad Hom. Il. 10.316

“He is base in his form: this is so he can sneak by you because he’s unremarkable. But he does want to be conveyed in the place of Achilles on his horses!”

εἶδος μὲν ἔην κακός: ἵνα ὡς ἄσημος λάθῃ. οὗτος δὲ ἤθελεν ἀντὶ ᾿Αχιλλέως ὀχεῖσθαι τοῖς ἵπποις.

As I have discussed in connection to Thersites, Greek physiognomy posits an overlap between looks and ethics. An ugly person, the logic goes, is also a bad person. In the mind of the scholiasts, Dolon’s wealth is a marker of Greed and corruption (which is a later belief rather than a Homeric one) and his greed indicates a craven or corruptible character. Again, Dué and Ebbott note “Dolon’s ugliness, by comparison, is not dwelled upon, and does not seem to provoke any particular strong reaction, whether ridicule, repulsion, or irritation.” I think this is a smart observation that points to the kakos (‘ugly, base’) perhaps more indicating a problematic character. The scholiasts take the mention of Dolon’s sisters as a potential indication that he is unmanly (or cowardly) because he was always with girls; while they also use wealth as an explanation for his character.

The striking combination of acknowledging that Dolon is ugly/base but swift-footed also binds him in some way to Achilles who receives a similar description twenty-two times in the epic (again, following Dué and Ebbott). I think this anticipates his speech in inviting us to compare him to Achilles before he makes the hubristic request of receiving the hero’s horses as a reward.

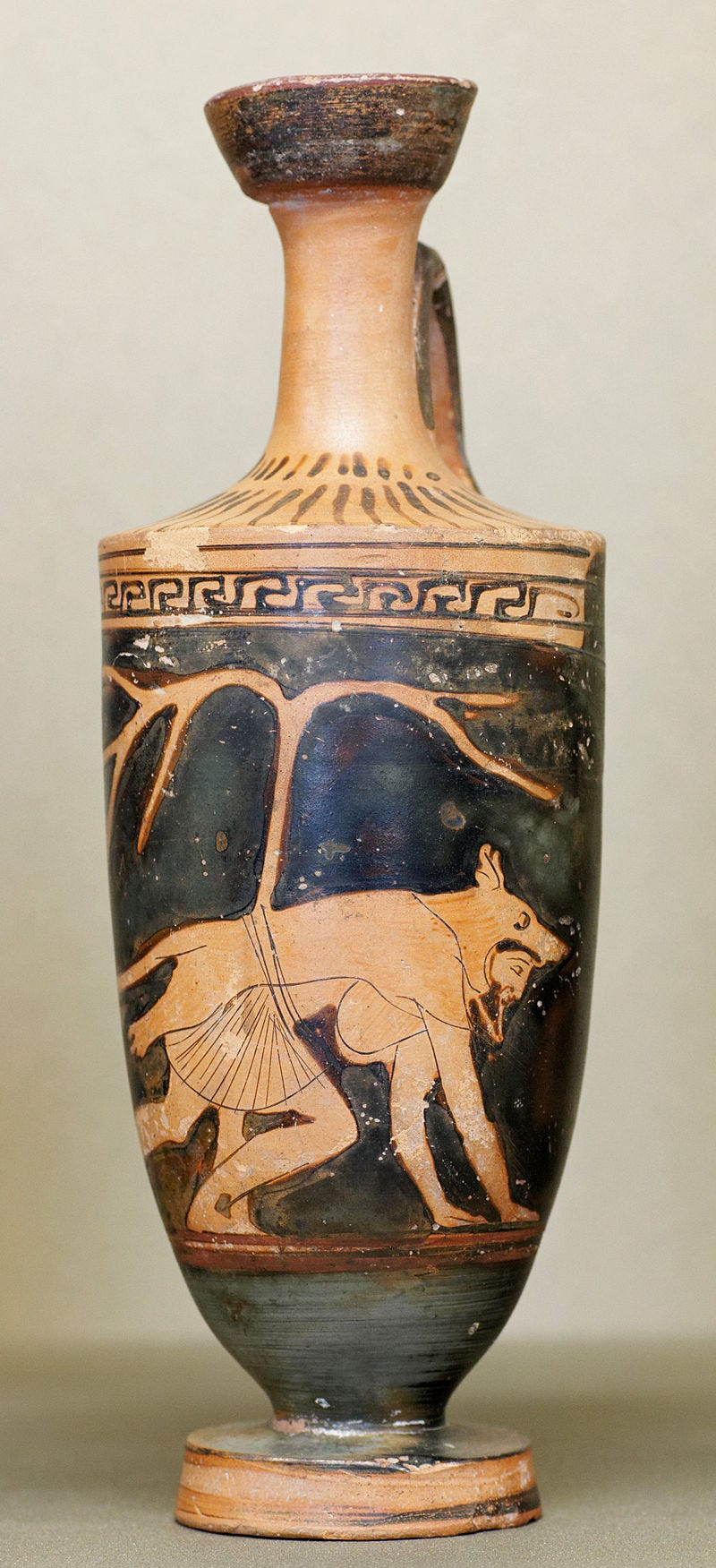

I think one could almost say that Dolon’s entire narrative is anticipated by this speech introduction and the value judgments implied therein. But this passage is not just a good overview of Homeric structures (the device of introducing a new character, value judgments for that character, anticipation of those themes) but it also implies a complexity of composition. I don’t think that we would see such correlation of speech and introduction nor such significant anticipation of a brief character’s outcome, with a passage that was not in some way repeated or traditional. What I mean by this is that the compositional ties of the Doloneia are integrated enough to suggest strongly that this is a well-structured and planned episode and has been performed on many occasions. For me, this complexity countermands any academic concern that Dolon is ‘untraditional’. (Whatever that really means: Dolon appears in unconnected images like the vase below and he is a rather different character in the Rhesus attributed to Euripides.)

Homeric poetry can introduce or adapt characters and figures to its own ends. I think Dolon here has been set up for a rather particular purpose. Dolon’s relationship to Achilles, moreover, in terms of the shared epithet and the former’s depiction as greedy and cowardly, asks us to think about heroism in response to the actions of book 9. Book 9 deconstructs our notion of Achilles as a hero and leaves us wondering what choice he will make and what he will do if he is not motivated by gold, gifts, or honor. Book 10 sets different models of heroism into play: Dolon contrasts with Diomedes and Odysseus (who are motivated by horses too, in the end!), but he also helps us think about individuals, the war, and communities. Dolon is a straight up mercenary with swift feet: his story functions to help us think about Achilles as a ‘hero’.

(If this doesn’t help explain why book 10 is important to the Iliad, I don’t know what will. Well, except for the political theme too....)

Bibliography on book 10 and the Doloneia

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Davidson, Olga Merck. “Dolon and Rhesus in the ‘Iliad.’” Quaderni Urbinati Di Cultura Classica 1 (1979): 61–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/20538562.

Dué, Casey, and Mary Ebbott. 2010. Iliad 10 and the Poetics of Ambush: A Multitext Edition with Essays and Commentary. Hellenic Studies Series 39. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Fenik, B. 1964. Iliad X and the Rhesus: The Myth. Collection Latomus 73. Brussels.

Haft, Adele J. “‘The City-Sacker Odysseus’ in Iliad 2 and 10.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 120 (1990): 37–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/283977.

Sheldon, Rose Mary. “THE ILL-FATED TROJAN SPY.” American Intelligence Journal 9, no. 3 (1988): 18–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44325966.

Stagakis, George. “DOLON, ODYSSEUS AND DIOMEDES IN THE ‘DOLONEIA.’” Rheinisches Museum Für Philologie 130, no. 3/4 (1987): 193–204. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41233632.

STEINER, D. “‘Wolf’s Justice’: The Iliadic Doloneia and the Semiotics of Wolves.” Classical Antiquity 34, no. 2 (2015): 335–69. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26362659.

West. M.L. 2011. The Making of the Iliad: Disquisition and Analytical Commentary. Oxford.

Some things on speech framing

Beck, Deborah. “Speech Introductions and the Character Development of Telemachus.” The Classical Journal 94, no. 2 (1998): 121–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3298206.

Beck, Deborah. “Odysseus: Narrator, Storyteller, Poet?” Classical Philology 100, no. 3 (2005): 213–27. https://doi.org/10.1086/497858.

Beck, Deborah. 2005. Homeric Conversation. Hellenic Studies Series 14. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Edwards, Mark W. “Homeric Speech Introductions.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 74 (1970): 1–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/310994.

Horn, Fabian. “Ἔπεα Πτερόεντα Again: A Cognitive Linguistic View on Homer’s ‘Winged Words.’” Hermathena, no. 198 (2015): 5–34. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26671604.

Riggsby, Andrew M. “Homeric Speech Introductions and the Theory of Homeric Composition.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 122 (1992): 99–114. https://doi.org/10.2307/284367.