This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis. Last year this substack provided over $2k in charitable donations.

At the beginning of book 13, soon after the Trojans have broken through the Greek fortifications around their ships, Poseidon intervenes in the action and rallies the Greeks to defend themselves. The intervention, however, has a few interesting features that may reflect on how we understand the gods’ functions in epic.

The Homeric gods are simultaneously representations of divine forces/entities who may (or may not) have reflected audiences beliefs and also actors in and upon the plot of epic. By intersecting between these two domains, they can also offer metaphysical and epistemological reflections, by which I mean, the limits of what humans can do and know and what the nature of the world between mortal and god may be. This reflection is, to be fair, more an issue of refraction (to borrow Donna Wilson’s term from her 2002 book).

When it comes to divine intervention, as I have mentioned before, I think part of what we are supposed to be inspired to consider as audience members is the interplay between human agency and determinism. The feature of double determination, where actions are given divine and human causes, for example, allows us to see both how events look from the divine perspective and how they might look from a mortal one. The reason I use the word ‘refraction’ here is that Homer does not have a single or simple way the human and divine worlds engage: it shifts throughout the epic, now here and there, inviting audiences to consider different ways of framing causality, fate, and human action.

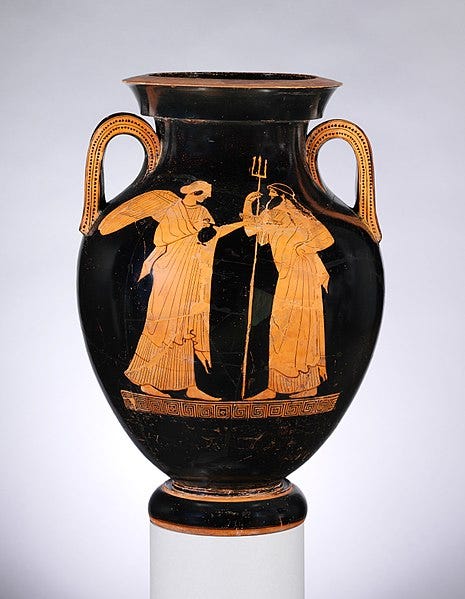

The intervention in this book introduces metanarrative features of divine presence as well. Readers have long observed that divine viewing shapes the way the audience may see the action: gods comment on mortal events, meddle in them, and train the audience’s gaze from one place to another. This scene is especially interesting because Poseidon’s action is the result of his viewing of the action alongside his rooting interest in the outcome of the game. But in addition to that, Poseidon also intervenes indirectly: he takes on the guise of a mortal and even seems to play the part by imitating what the mortal might be likely to say. As such, this seen may have mimetic implications, by which I mean it may provide insights into how Homeric poetry thinks both about the characterization of individual heroes and how it imagines audience members reading the epic’s action.

Iliad 13.39-45

“The Trojans were churning like whirlwinds or a gale

As the followed Priam’s son Hektor insatiably

Shouting, screaming—they imagined they would take

The Achaeans ships and kill all the best men among them.

But the earthshaker Poseidon who grips the land

Rose from the deep sea to urge the Argives on,

Putting on the appearance and tireless voice of Kalkhas”Τρῶες δὲ φλογὶ ἶσοι ἀολλέες ἠὲ θυέλλῃ

῞Εκτορι Πριαμίδῃ ἄμοτον μεμαῶτες ἕποντο

ἄβρομοι αὐΐαχοι· ἔλποντο δὲ νῆας ᾿Αχαιῶν

αἱρήσειν, κτενέειν δὲ παρ’ αὐτόθι πάντας ἀρίστους.

ἀλλὰ Ποσειδάων γαιήοχος ἐννοσίγαιος

᾿Αργείους ὄτρυνε βαθείης ἐξ ἁλὸς ἐλθὼν

εἰσάμενος Κάλχαντι δέμας καὶ ἀτειρέα φωνήν·

A scholion explains Poseidon’s choice as “since he was about to speak against Agamemnon on Achilles’ behalf, he is disguised as Kalkhas to make it more believable” ἐπεὶ ὑπὲρ ᾿Αχιλλέως κατὰ ᾿Αγαμέμνονος μέλλει λέγειν (sc. Ν 107—14), πρὸς τὸ πιστωθῆναι Κάλχαντι εἴκασται, schol. bT ad Il 13.45 ex. B). The scholion’s explanation here is more than a little disappointing. It reads into Poseidon’s choice the content of his subsequent speech—and not even the immediate one in which he addresses the two Ajaxes. Soon after that, he finds Teucer, and Lêitos, Pêneleon, Thoas, Dêipuros, Mêrionês, and Antilochos. With the exception of Thoas, these are not the leading lights of the Achaeans—but they are those who are left, thanks to the spate of injuries suffered in book 11. As a scholiast notes, Poseidon calls them “young men” and they are the ones who are left. The tone and content of his speech is fascinating

Iliad 13.107-114

But now [the Trojans] are fighting far from the city among the hollow shops

Thanks to the wickedness of our leader and the negligence of the army.

They are not willing to defend the shift ships because they have been struggling

With him—yet still, they are being killed alongside them.

But even if it is totally true that the cause of this

Is the hero son of Atreus, wide-ruling Agamemnon

Because he dishonored swift-footed Peleus’ son,

There is no way for us to hang back from war.

Let’s repair this quickly—the minds of good men are surely reparable.”νῦν δὲ ἑκὰς πόλιος κοίλῃς ἐπὶ νηυσὶ μάχονται

ἡγεμόνος κακότητι μεθημοσύνῃσί τε λαῶν,

οἳ κείνῳ ἐρίσαντες ἀμυνέμεν οὐκ ἐθέλουσι

νηῶν ὠκυπόρων, ἀλλὰ κτείνονται ἀν’ αὐτάς.

ἀλλ’ εἰ δὴ καὶ πάμπαν ἐτήτυμον αἴτιός ἐστιν

ἥρως ᾿Ατρεΐδης εὐρὺ κρείων ᾿Αγαμέμνων

οὕνεκ’ ἀπητίμησε ποδώκεα Πηλεΐωνα,

ἡμέας γ’ οὔ πως ἔστι μεθιέμεναι πολέμοιο.

ἀλλ’ ἀκεώμεθα θᾶσσον· ἀκεσταί τοι φρένες ἐσθλῶν.

What a speech! A scholion notes significant ambiguity in this final line because the verb ἀκεώμεθα does not have an object. A T scholion suggests it could be “the anger of Achilles, or the negligence for which he was reproaching them” (τὴν ἔριν ἢ τὴν μῆνιν ᾿Αχιλλέως, ἢ τὴν ἀμέλειαν, ἣν αὐτοῖς ὀνειδίζει, schol. T ad Hom. Il. 13.115c). The proverbial claim—that noble men have minds that are pliable—doesn’t make the matter any clearer, because it could refer to Achilles and Agamemnon, the Greeks who are holding back, or everyone. While I tend to prefer readings that preserve ambiguity, I think that the closest referent is ἡμέας (“us”), which puts the onus on the addressees without foreclosing other possibilities (e.g., the arguing jerks who started it all).

The language from the beginning of this passage is critical of the Greeks and their leadership and aims to claim common ground with the addressees while filling them with a sense of shame that it has gone this far. Poseidon is acting the part of an audience member who is fed up with action that has taken a different course than he expected. His intervention strains against “Zeus’ plan” and tries to realign the inverted action of this poem with the larger “superstory” (to use Rachel Lesser’s term) of the Trojan War. In this, we can imagine Poseidon in that role of divine voyeur, frustrated at the story he watches.

At the same time, he provides an interpretation of the events for the mortals. As a god, Poseidon has heard about Zeus’ plans—he just doesn’t care about them. Note that he does not mention divine will in this passage; instead, he focuses on the Achaean political drama. He claims that Agamemnon is to blame, which is strong language in the epic tradition, yet by lumping Achaean cowardice into the conversation, he makes the very reasonable—and persuasive—argument that the Achaean army is a lot more than one (or two) men. As an interpreter of the action of the poem, then, Poseidon passes judgment on all of the Achaeans and instrumentalizes his judgment as an act of persuasion.

Disguised as Kalkhas, Poseidon also picks a line of argumentation that will resonate with these youngest of heroes who have seen the actual best of the Achaeans sidelined by pettiness, rage, and actual martial injuries. In my reading now, Poseidon is an actor who has donned a persona to move mortals to action; at the same time, he is a performer who has taken on a role that may also speak to Homeric poetics. Can we imagine Poseidon here as echoing the choices for speeches made by Homeric singers and from this can we make deductions on how they shape and shift the content of each speech to persuade or otherwise shape audience reaction?

My intuition on this is yes. There may be a homology to explore between this scene and Thucydides famous description of how his speeches correspond to what needed to be said (or what was appropriate to the situation). One would also need to look at all of the disguised speeches in the Iliad with careful attention to the audiences targeted to explore this idea further. But Poseidon gave us a start. As a figure in a mask, interpreting the scene for us, Poseidon is an actor, a divine hypocrite (keeping in line with the original meaning of the Greek word). But the tension between the story he tells as Kalkhas and the story we see as the audience helps us understand the epic even more.

A list of all my posts on the Iliad

Other posts on Iliad 13

The Iliad's Longest Day: Starting to Make Sense of Book 13: Time and the Iliad; Temporal Structure; Chronology

Epic Narratives and their Local Sidekicks: On Cretans in Iliad 13: Epic, epichoric, and Panhellenic; Crete

A Heroic Tale Curtailed: Homeric Digressions and Iliad 13: Digressions/paranarratives or inset tales; Idomeneus; Kassandra

footnote: "Athena plays favorites while Poseidon is a team leader": does this remain true in The Odyssey? Just spit-balling here but wonder if the Iliad contains reasons for the Athena-Poseidon split of the Odyssey.

A question I had while reading this book was, how is it appropriate that Poseidon, the sea god, just happens to come to the forefront of the action when the battle reaches the seashore and the ships? Why is it appropriate for the sea god to interfere exactly at this point?

Meanwhile, Joel's translation of 39-44 brings into high relief the extent to which the Four Elements as a whole play a role in these passages: the Trojans are “like a whirlwind” (Hector is in other places described as a whirlwind). Also: “the earthshaker Poseidon who grips the land rose from the deep sea” — a lot of Elements in those lines. On top of this, we know that Hector brings fire — what's at stake here is the burning of the ships -- so all of the elements are embroiled in this battle.

You wonder if maybe the Trojans represent fire and air while the Greeks represent land and water? And yet, in later books, the rivers are on the side of the Trojans, and Hephaistos, who brings fire, is on the side of the Greeks. And Hector is not just described as being like a whirlwind but also described as being like a stone.

As to the point of Joel's post: Poseidon definitely brings an energy of his own to the way he interferes in the affairs of humankind, quite unlike Athena's energy in book 5. Athena plays favorites while Poseidon is a team leader. It is interesting that the gods present themselves as mortals (as opposed to as themselves) and must make a decision about which mortal's likeness -- what persona, what character -- they will adopt.