This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 13. Here is a link to the overview of book 11 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 13 of the Iliad is the continuation of a day of fighting that begins with book 11 and does not actually end until book 18 (see below for more). Where book 12 so the momentous breaching of the Achaean Wall and book 14 features the seduction of Zeus, 13 turns out to appear a little more forgettable. Part of this is because of the steady wounding of the most prominent Greeks that prompted Achilles to send Patroklos to investigate in book 11. The suffering of the Greeks is all part of Zeus’ plan to honor Achilles….as the story goes.

But another reason for this plot is political: despite how many of their captains fall, the Achaeans still seem to have more leaders to stand in place of the wounded and lead on the battle. Book 13 presents something of an aristeia for the Cretan commander Idomeneus, who rallies the Greeks along with Meriones. Their resistance to the Trojan onslaught is facilitated in part by Poseidon (who is opposing Zeus, as surreptitiously as the god of oceans and earthquakes can do anything) and the contrasting dysfunction of the Trojan leadership. In service of this last subplot, book 13 also features another conversation between Hektor and his advisor Polydamas.

The plot of this book engages critically with the major themes I have noted to follow in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions, but the central themes I emphasize in reading and teaching book 13 are Politics, Gods and Humans and Narrative Traditions.

Counting Days, Making Space in the Iliad

As Grace Erny summarizes in her 2020 article on Iliad 13, this book has given interpreters fits. The structure isn’t as ‘geometric’ as book 6, it doesn’t have the same punch as book 12, and there’s no signature episode like we get in book 14. Erny argues that Idomeneus and Meriones in this book function as parallels–if not stand-ins–for the absent Achilles and Patroklos. (An argument I find pretty convincing.) She also adds that the emphasis on their identity as Cretans reveals important reflections of historical knowledge about Crete and its relationship with the rest of Greece (something else I find convincing). What I think we need to consider more of is why this content appears at this point during the epic.

Book 13 is pretty much just over the mid-point of the epic. The fact that as an audience we are treated to this second or third string of Achaean leaders indicates just how bad things are going for the Greeks and may in fact put a strain on our attention (which may explain in part both the somewhat odd and jocular tone of the Cretan captains as well as the flirtation with other narrative traditions and possibilities: the near-miss of having Aeneas face Idomeneus or the somewhat belated advice Polydamas offers to Hektor to rally his troops. Book 13 tests the limits of the Achaeans, the story, and audience patience.

I must confess that my comments in this regard are rooted almost entirely in my own history of frustration with these books: in a way, books 13-15 of the Iliad are not that different from books 13-15 in the Odyssey. Audiences know what needs to happen (Patroklos needs to go to Achilles in the Iliad; Odysseus needs to meet Telemachus in the Odyssey) but the narrative increases our suspense and expands the consequences of what is about to happen by fleshing out this narrative world.

One of the scholarly interventions that helped me see these books differently in the Iliad is J. S. Clay’s Homer’s Trojan Theatre. The book does a great job of laying out the stability and accuracy of movements and space depicted within the battlebooks. The visualization Clay provides on her website demonstrates how well-thought out the process is. The actions of books 12-17 are not just about delaying the inevitable or increasing our suspense, they also reveal a sophisticated narrative plan and advance important themes (like those of politics).

But I also think that the potential of these books to exhaust is important for the emotional aims of the epic as well. If Clay’s emphasis on the consistency of Homeric spatial reference helps us understand how thoroughly coordinated these events are, thinking about the passage of time can help us better understand how the audience moves through the poem as one of the combatants.

When I talk about time in the Iliad, I usually just blithely say that the Iliad is metonymically related to the Trojan War, it represents the larger themes and concerns of 10 years through 50 some odd days of war. The temporal breakdown in the Iliad, however, is more complicated than that by far. There are several online discussions of how many days there are in the Iliad and how we should split them up. (and another here!)

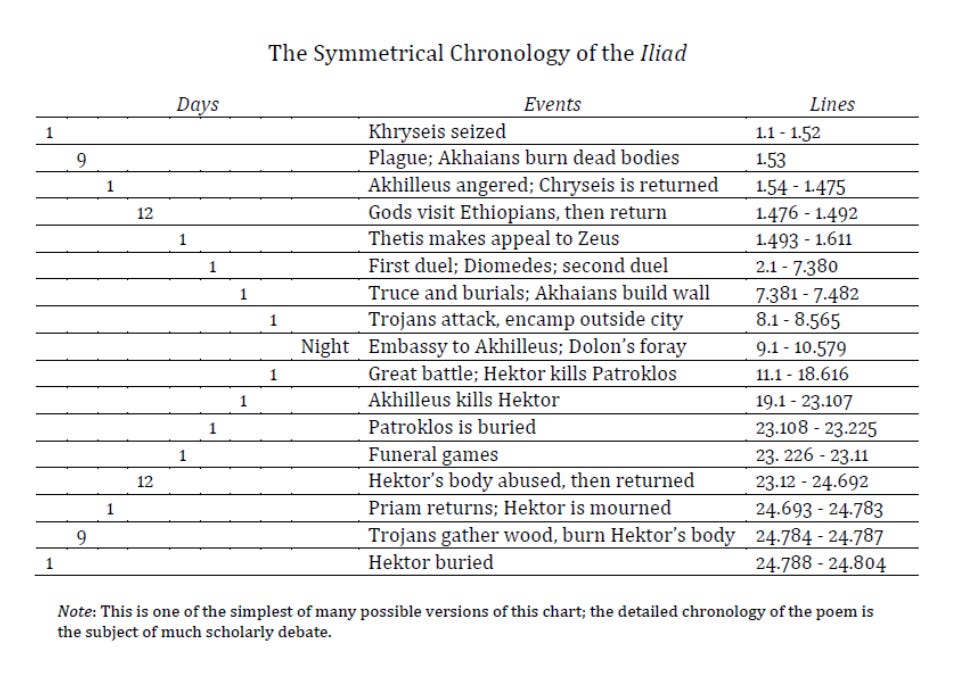

Here is an old fashion chart that splits them evenly across units of 11 days

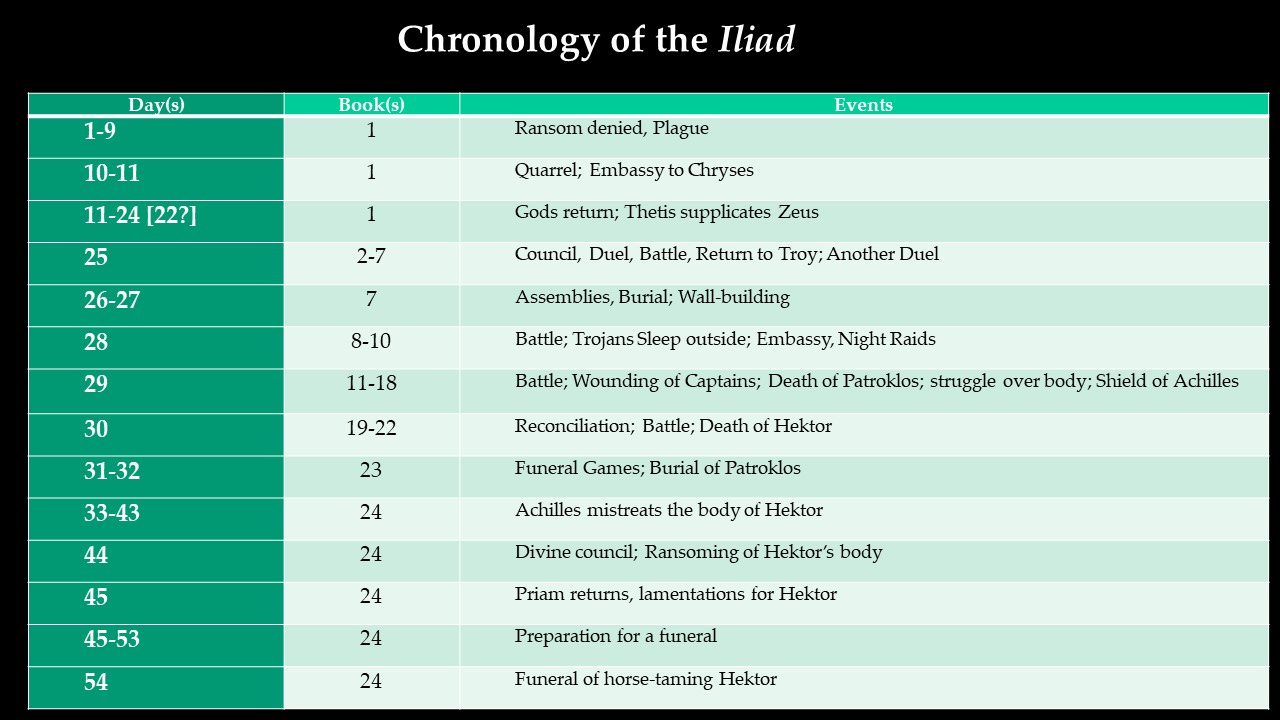

I think this is useful, but it doesn’t give a sense of the narrative weight to the way the time is spent. I am a big fan of this chart by Edward Mendelson that attempts to show the passage of time is split in a symmetrical way. Ultimately, I think the chronology is nearly symmetrical, but not exactly as Mendelson lays out.

Below I have tried my own hand at making some sense of the chronology. The important thing is how much narrative weight goes into a single day. Narratology instructs that there is an important difference between “story time” (the sequence and events of a story as they are experienced by the characters, if they were laid out as just a sequence) and “narrative time”, the way the particular narrative arranges them and how they are experienced by the audience.

Most narrative time we experience is significantly edited or altered from ‘story time’ or the time of ‘real life’. With the exception of experiments or shticks like the television show 24, we rarely encounter narratives that try to match the time of the telling to what might be the ‘real’ time of the events. I think we may want to start considering the battlebooks of the Iliad as an early attempt to do so.

The fight from books 11-18 is fully one third of the epic, but it is only one day of the 54 referenced in the poem. Even if we only focus on the 12 fuller days that are depicted in the epic (leaving aside the 42 days glossed over in summary), we have 1/3 the epic endeavoring to describe 1/12 of the time that passes.

The narrative structure, I think, serves to show how time dilates during war–how it expands and contracts and shifts our experience of night and day. At the same time, it places an important narrative emphasis on the events that it contains: the suffering of the Achaeans requested by Achilles in book 1, culminating in the death of his own friend Patroklos and the re-tasking of Achilles’ rage to the Trojans from his own people. This attempt to bring story time and narrative time into alignment has an emotional impact on audiences, as they struggle to keep up with the action, to stay engaged, and to wade through the fog of war in anticipation of something (clearly) significant happening.

A Few further references for Iliadic chronology and narratology

Foster, B. O. “The Duration of the Trojan War.” The American Journal of Philology 35, no. 3 (1914): 294–308. https://doi.org/10.2307/289413.

Grethlein, J. (2006) Das Geschichtsbild der Ilias: eine Untersuchung aus phänomenologischer und narratologischer Perspektive, Göttingen

de Jong, I. J. (2004 [1987]) Narrators and focalizers: the presentation of the story in the Iliad, Bristol.

de Jong, I. J. and Nünlist, R. (eds.) (2007) Time in ancient Greek literature, Leiden and Boston.

Scott, John A. “The Assumed Duration of the War of the Iliad.” Classical Philology, vol. 8, no. 4, 1913, pp. 445–56. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/262533. Accessed 3 Jan. 2024.

Taplin, O. (1992) Homeric soundings: the shaping of the Iliad, Oxford: Clarendon.

Reading Questions for Book 13

How do Poseidon’s actions in book 13 change the way we think about the gods in the Iliad?

What does the conversation between Polydamas and Hektor in this book contribute to the political theme?

How do the depictions of Idomeneus and Aeneas change how we think about the Greek and Trojan Armies?

I will follow up with longer posts about Idomeneus, Crete, Aeneas, and Trojan Politics.

A starting bibliography on Book 13

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Cramer, David. “The wrath of Aeneas: Iliad 13.455-67 and 20.75-352.” Syllecta classica, vol. 11, 2000, pp. 16-33.

Erny, Grace. "Iliad 13, Homer’s Cretan Heroes, and “Cretan Exceptionalism”." Phoenix, vol. 74 no. 3, 2020, p. 197-219. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/phx.2020.0036.

Fenno, Jonathan Brian. “The wrath and vengeance of swift-footed Aeneas in Iliad 13.” Phoenix, vol. 62, no. 1-2, 2008, pp. 145-161.

Friedman, Rachel Debra. “Divine dissension and the narrative of the « Iliad ».” Helios, vol. 28, no. 2, 2001, pp. 99-118.

Kotsonas, Antonis. “Homer, the archaeology of Crete and the « Tomb of Meriones » at Knossos.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 138, 2018, pp. 1-35. Doi: 10.1017/S0075426918000010

McClellan, Andrew M.. “The death and mutilation of Imbrius in Iliad 13.” Yearbook of Ancient Greek Epic, vol. 1, 2017, pp. 159-174. Doi: 10.1163/24688487-00101007

Panegyres, Konstantine. “Ὄρεϊ νιφόεντι ἐοικώς: Iliad 13.754-755 revisited.” Mnemosyne, Ser. 4, vol. 70, no. 3, 2017, pp. 477-487. Doi: 10.1163/1568525X-12342271

Saunders, Kenneth B.. “The wounds in Iliad 13-16.” Classical Quarterly, N. S., vol. 49, no. 2, 1999, pp. 345-363. Doi: 10.1093/cq/49.2.345