This is one of a few posts dedicated to Iliad 24. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

In an earlier post, I wrote about how Priam’s journey to Achilles invokes themes of crossing to a liminal space between life and death. This space is also one where the regular boundaries between nations and peoples may not apply—it is a zone potentially open to different ways of engaging, of viewing the world. Once Priam arrives there, he receives rather specific advice from Hermes about supplicating Achilles, generating one of the most memorable scenes from ancient literature. I think that there is something special going on with how this scene achieves its impact that has something to tell us about how epic works in general and can answer in part why Aristotle thinks the Iliad is the most tragic of epics, not in form (as most assume) but in function and effect.

Let’s start with the scene

Homer, Iliad 24.477-512

Great Priam escaped the notice of [Achilles’ companions] when he entered the room

And he stood right next to him, clasping his knees and kissing his hands

Those terrible [deinas] murderous hands that had killed so many of his sons.

As when bitter ruin overcomes someone who killed a man

In his own country and goes to the land of others

To some rich man, and wonder [thambos] over takes those who see him.

So too did Achilles feel wonder [thambêsen] when he saw godlike Priam.

The rest of the people there were shocked [thambêsan] and they all looked at one another

Then Priam was begging as he addressed him.

“Divine Achilles, remember [mnêsai] your father—

The same age as I am, on the deadly threshold of old age.

The people who live around him are wearing him out,

I imagine, and there is no one there to ward off conflict and disaster.

But when that man hears that you are alive still,

He rejoices in his heart because he will keep hoping all his days

That he will see his dear son again when he comes home from Troy.

But I am completely ruined. I had many of the best sons

In broad Troy, but I think that none of them are left.

I had fifty sons when the sons of the Achaeans arrived here.

Nineteen of them were mine from the same mother,

And other women bore the rest to me in my home.

Rushing Ares loosened the limbs of many of them,

But the one who was left alone for me, who defended the city and its people

You killed as he warded danger from his fatherland,

Hektor, for whom I have home now to the Achaeans’ ships

To ransom him from you. And I am bringing endless exchange gifts.

But feel fame before the gods, Achilles, and pity [eleêson] him

Once you have remembered [mnsêsamenos] your father. I am more pitiful [eleeinoteros] still,

I who suffer what no other mortal on this earth has ever suffered,

putting the hand of the man who murdered my son to my mouth.’

So Priam spoke and a desire for mourning his father rose within him.

He took his hand and pushed the old man gently away.

The two of them remembered [tô mnêsamenô]: one wept steadily

For man-slaying Hektor, as he bent before Achilles’ feet,

But Achilles’ was mourning his own father, and then in turn

Patroklos again—and their weeping rose throughout the home.”τοὺς δ’ ἔλαθ’ εἰσελθὼν Πρίαμος μέγας, ἄγχι δ’ ἄρα στὰς

χερσὶν ᾿Αχιλλῆος λάβε γούνατα καὶ κύσε χεῖρας

δεινὰς ἀνδροφόνους, αἵ οἱ πολέας κτάνον υἷας.

ὡς δ’ ὅτ’ ἂν ἄνδρ’ ἄτη πυκινὴ λάβῃ, ὅς τ’ ἐνὶ πάτρῃ

φῶτα κατακτείνας ἄλλων ἐξίκετο δῆμον

ἀνδρὸς ἐς ἀφνειοῦ, θάμβος δ’ ἔχει εἰσορόωντας,

ὣς ᾿Αχιλεὺς θάμβησεν ἰδὼν Πρίαμον θεοειδέα·

θάμβησαν δὲ καὶ ἄλλοι, ἐς ἀλλήλους δὲ ἴδοντο.

τὸν καὶ λισσόμενος Πρίαμος πρὸς μῦθον ἔειπε·

μνῆσαι πατρὸς σοῖο θεοῖς ἐπιείκελ’ ᾿Αχιλλεῦ,

τηλίκου ὥς περ ἐγών, ὀλοῷ ἐπὶ γήραος οὐδῷ·

καὶ μέν που κεῖνον περιναιέται ἀμφὶς ἐόντες

τείρουσ’, οὐδέ τίς ἐστιν ἀρὴν καὶ λοιγὸν ἀμῦναι.

ἀλλ’ ἤτοι κεῖνός γε σέθεν ζώοντος ἀκούων

χαίρει τ’ ἐν θυμῷ, ἐπί τ’ ἔλπεται ἤματα πάντα

ὄψεσθαι φίλον υἱὸν ἀπὸ Τροίηθεν ἰόντα·

αὐτὰρ ἐγὼ πανάποτμος, ἐπεὶ τέκον υἷας ἀρίστους

Τροίῃ ἐν εὐρείῃ, τῶν δ’ οὔ τινά φημι λελεῖφθαι.

πεντήκοντά μοι ἦσαν ὅτ’ ἤλυθον υἷες ᾿Αχαιῶν·

ἐννεακαίδεκα μέν μοι ἰῆς ἐκ νηδύος ἦσαν,

τοὺς δ’ ἄλλους μοι ἔτικτον ἐνὶ μεγάροισι γυναῖκες.

τῶν μὲν πολλῶν θοῦρος ῎Αρης ὑπὸ γούνατ’ ἔλυσεν·

ὃς δέ μοι οἶος ἔην, εἴρυτο δὲ ἄστυ καὶ αὐτούς,

τὸν σὺ πρῴην κτεῖνας ἀμυνόμενον περὶ πάτρης

῞Εκτορα· τοῦ νῦν εἵνεχ’ ἱκάνω νῆας ᾿Αχαιῶν

λυσόμενος παρὰ σεῖο, φέρω δ’ ἀπερείσι’ ἄποινα.

ἀλλ’ αἰδεῖο θεοὺς ᾿Αχιλεῦ, αὐτόν τ’ ἐλέησον

μνησάμενος σοῦ πατρός· ἐγὼ δ’ ἐλεεινότερός περ,

ἔτλην δ’ οἷ’ οὔ πώ τις ἐπιχθόνιος βροτὸς ἄλλος,

ἀνδρὸς παιδοφόνοιο ποτὶ στόμα χεῖρ’ ὀρέγεσθαι.

῝Ως φάτο, τῷ δ’ ἄρα πατρὸς ὑφ’ ἵμερον ὦρσε γόοιο·

ἁψάμενος δ’ ἄρα χειρὸς ἀπώσατο ἦκα γέροντα.

τὼ δὲ μνησαμένω ὃ μὲν ῞Εκτορος ἀνδροφόνοιο

κλαῖ’ ἁδινὰ προπάροιθε ποδῶν ᾿Αχιλῆος ἐλυσθείς,

αὐτὰρ ᾿Αχιλλεὺς κλαῖεν ἑὸν πατέρ’, ἄλλοτε δ’ αὖτε

Πάτροκλον· τῶν δὲ στοναχὴ κατὰ δώματ’ ὀρώρει.

In a few posts I have riffed on my take on how storytelling works, in the world and in the Iliad, using Mark Turner’s concept of the cognitive blend from The Literary Mind. When we hear narratives, we don’t replicate them in our minds, instead we create overlays and blends between our own experiences and the stories we hear. This is part of what just happens naturally based on how stories work, but it is also a feature that facilitates sympathy and empathy.

In the speech above, I have tried to emphasize Greek words that signal poetic creation/memory (words of remembering) in setting up a parallel (Priam relating his loss to Achilles’ father’s potential loss; both heroes seeing their own pain in another. At the same time, I have focused on the affective emphasis in the passage and the set-up, in particular on feelings of “pity” and “wonder” or ‘fear”. Wonder/surprise is operative in characterizing Achilles’ response and his ability to feel pity, which in this context seems to correlate to what happens in the narrative, which is that Priam and Achilles together engage in a creative act of remembering that stems from a shared performance (Priam’s speech) but extends to their individual experiences and a very real difference in the way they internally narrativize their brief common ground.

The situation is set up in a way that prizes pity. Prior to the supplication, Hermes provides Priam with very specific instructions (Iliad 24.354-357)

“Think carefully, Son of Dardanus, this is made for careful thought:

I see a man I think would tear us apart quickly—

Let’s either escape on the horses or instead

Embrace his knees and beg him to have pity.”φράζεο Δαρδανίδη· φραδέος νόου ἔργα τέτυκται.

ἄνδρ’ ὁρόω, τάχα δ’ ἄμμε διαρραίσεσθαι ὀΐω.

ἀλλ’ ἄγε δὴ φεύγωμεν ἐφ’ ἵππων, ἤ μιν ἔπειτα

γούνων ἁψάμενοι λιτανεύσομεν αἴ κ’ ἐλεήσῃ.

And this follows a very specific mention of Zeus sending Hermes to Priam to begin with because he pitied him (“When [Zeus] saw the old man, he pitied him and / Quickly addressed his own son Hermes...”, ἐς πεδίον προφανέντε· ἰδὼν δ' ἐλέησε γέροντα, / αἶψα δ' ἄρ' ῾Ερμείαν υἱὸν φίλον ἀντίον ηὔδα, 24.354-57). And this is far from the first time where common ground is established through mourning. As I discuss in a post on book 19 and Achilles’ lament for Patroklos there, we find evidence of people witnessing witnessing others’ acts of mourning and remembering as a beginning of their own remembrance and reflections. First, the women who grieve for Patroklos turn from him to their own pains (῝Ως ἔφατο κλαίουσ’, ἐπὶ δὲ στενάχοντο γυναῖκες / Πάτροκλον πρόφασιν, σφῶν δ’ αὐτῶν κήδε’ ἑκάστη, 19.302-303), then Achilles himself moves from topic to topic, comparing his loss in one instance to other possible losses, finally inspiring the other old men to mourn along with him, using his pain kindling for their own fires of memory and loss.

Homer, Iliad 19. 309-340

“He said this and dispersed the rest of the kings,

But the two sons of Atreus remained along with shining Odysseus,

Nestor, Idomeneus, and the old horse-master Phoinix

All trying to bring him some distraction. But he took no pleasure

In his heart before he entered the jaws of bloody war.

He sighed constantly as he remembered and spoke:

‘My unlucky dearest of friends it was you who before

Used to offer me a sweet meal in our shelter

Quickly and carefully whenever the Achaeans were rushing

To bring much-lamented Ares against the horse-taming Achaeans.

But now you are lying there run-through and my fate

Is to go without drink and food even though there inside

Because I long for you. I couldn’t suffer anything more wretched than this

Not even if I learned that my father had died,

Who I imagine is crying tender tears right now in Pththia

Bereft of a son like this—but I am in a foreign land,

Fighting against the Trojans for the sake of horrible Helen.

Not even if I lost my dear son who is being cared for in Skyros,

If godlike Neoptolemos is at least still alive—

Before the heart in my chest always expected that

I alone would die far away from horse-nourishing Argos

Here in Troy, but that you would return home to Phthia

I hoped you would take my child in the swift dark ship

From Skyros and that you would show to him there

My possessions, the slaves, and the high-roofed home.

I expect that Peleus has already died or

If he is still alive for a little longer he is aggrieved

By hateful old age and as he constantly awaits

Some painful message, when he learns that I have died.”

So he spoke while weeping, and the old men mourned along with him

As each of them remembered what they left behind at home.

And Zeus [really] felt pity when he saw them mourning”

This passage helps us see as well how Achilles’ grief is metonymic for his own loss and others as well. Note how the speech’s introduction positions Achilles as mourning constantly “as he recalled” (μνησάμενος δ' ἁδινῶς...). The end of the speech reminds us that other people are listening to him as well and are changed and moved in turn by his mourning. The Greek elders mourn in addition (ἐπὶ δὲ στενάχοντο γέροντες) and not because of Patroklos, but as they recall what they have left behind (μνησάμενοι τὰ ἕκαστος ἐνὶ μεγάροισιν ἔλειπον). This repeated participle mnêsamenoi is often connected with the poetic power to remember and tell the stories of the past.

Achilles’ grief presents a narrative others see themselves in, they project their experiences into his pain and grieve alongside him, anticipating to a great part that powerful moment in book 24 when Achilles and Priam find in each other a reminder to weep for what they have individually lost. And this is clear from Priam’s own language, echoing the narrator’s Zeus: “But revere the gods, Achilles, and pity him, / thinking of your own father. And I am more pitiable still...”(ἀλλ' αἰδεῖο θεοὺς ᾿Αχιλεῦ, αὐτόν τ' ἐλέησον / μνησάμενος σοῦ πατρός· ἐγὼ δ' ἐλεεινότερός περ, 24.503-4).

This moment is a crucial confirmation of the Homeric expectation that words and experiences people hear should (and do) prompt reflection on their own lives (as well as the situation in general). The sequence also anticipates other audiences as well. A simple but extremely useful distinction from narratology (the way narratives are structured and work) is between internal and external audiences. Internal audiences are characters within a narrative who observe and (sometimes) respond to what is going on. External audiences are those outside the narrative (mostly those in the ‘real’ world).

A theoretical suggestion from this is that the responses of internal audiences can guide or often complicate the way external audiences receive the narrative. Another internal audience appears when we find out Zeus is watching the scene and he feels pity: together the women, the elders, and Zeus present a range of potential reactions for external audiences: the mortals reflect on their own lives and the losses they suffer or those to come. Zeus watches it all and feels pity and tries to do something to help, sending Athena to provide Achilles with the sustenance he will not take on his own. Here, we might even imagine the narrative offering an ethical imperative to response to other’s stories. It is not enough to think about yourself or merely to be moved to pity by seeing the reality that others may feel as deeply and painfully as you. Zeus’s model suggests that if you are in power and can do something to intervene, even something minor, when you notice another’s suffering, then you should do what you can.

The exchange between Priam and Achilles is the culmination of this narrative arc and it has individual ramifications as well as potential information for how we should understand the epic genre. One of the fascinating things in this movement is the sustained importance of pity. Scholars have taken different approaches to this. Dean Hammer (2002) has emphasized how Achilles’ view of his relation to other dominates his “ethical stance”, arguing for a transformation that allows him to feel pity for Priam because his experiences within the epic have changed how he views suffering. Graham Zanker makes a similar argument in The Heart of Achilles where he emphasizes that it is important that Achilles came to this change on his own, that the gods did not support him: His present behavior is therefore a pole apart from his cruel rejection of the supplications of men like Tros, Lykaon, and Hektor. Homeric theology allows Achilles' present generosity, or rather magnanimity, to be based on his own volition” (Zanker 1996, 120). Glenn Most (2003) has seen the thematic core of the Iliad as relying not merely on rage but on the dynamic between anger and pity. Jinyo Kim’s full study The Pity of Achilles traces the language of pity throughout the Iliad to demonstrate that this theme is part of what signals the epic’s unity. For Kim, “Achilles’ pity for Priam constitutes no incidental detail, but is instead the thematic catalyst of the reconciliation’ (2000, 12).

Marjolein Oele (2011) has suggested that when Priam and Achilles cry together they come to identify with each other in a way that anticipates Aristotle’s comments throughout his work—their unique moment isn’t merely pity, but instead it is a shared experience of suffering and wonder that helps them accomplish what Aristotle would call recognition. While most scholars see some relationship between the dramatic personae of epic and tragic performances (see especially Irene J. F. De Jong’s 2016 essay, Stroud and Robertson’s essay, or Emily Allen-Hornblower’s 2015 book), I think there has been less focus on the affective impact modeled within epic poetry. Epic’s gradual but persistent emphasis on creative acts of memory as loci for exploring one’s own experiences in a shared common frame reminds me of Aristotle’s famous focus on “pity and fear”.

Aristotle, Poetics 1449b21-27

“We’ll talk later about mimesis in hexameter poetry and comedy. For now, let’s chat about tragedy, starting by considering the definition of its character based on what we have already said. So, tragedy is the imitation (mimesis) of a serious event that also has completion and scale, presented in language well-crafted for the genre of each section, performing the story rather than telling it, and offering cleansing (catharsis) of pity and fear through the exploration of these kinds of emotions.”

Περὶ μὲν οὖν τῆς ἐν ἑξαμέτροις μιμητικῆς καὶ περὶ κωμῳδίας ὕστερον ἐροῦμεν· περὶ δὲ τραγῳδίας λέγωμεν ἀναλαβόντες αὐτῆς ἐκ τῶν εἰρημένων τὸν γινόμενον ὅρον τῆς οὐσίας. ἔστιν οὖν τραγῳδία μίμησις πράξεως σπουδαίας καὶ τελείας μέγεθος ἐχούσης, ἡδυσμένῳ λόγῳ χωρὶς ἑκάστῳ τῶν εἰδῶν ἐν τοῖς μορίοις, δρώντων καὶ οὐ δι᾿ ἀπαγγελίας, δι᾿ ἐλέου καὶ φόβου περαίνουσα τὴν τῶν τοιούτων παθημάτων κάθαρσιν.

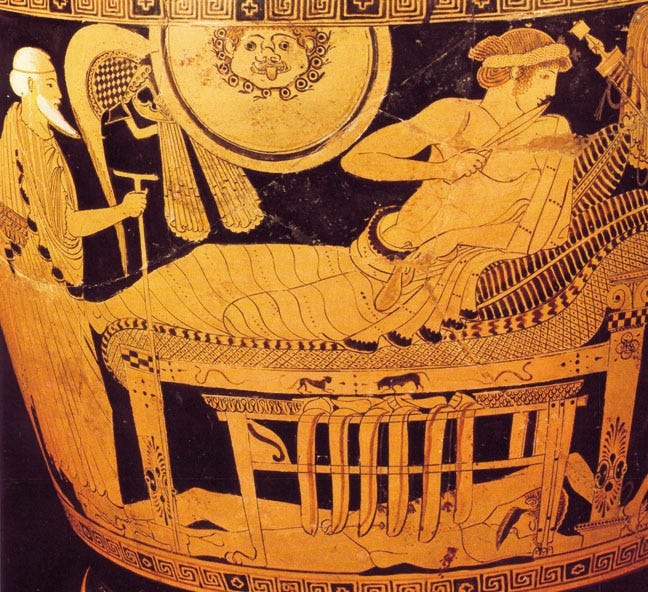

There are several other passages throughout his work where Aristotle adds to his conceptualization to include reversal (peripateia) and recognition (anagnorisis), but in the steady focus on memory/narrative (mimesis and memory), as well as the experience of pity and fear/wonder I have emphasized in book 24, I see a much stronger tragic/dramatic potential within Homer. And this is supported in part by one of the few scenes we have from the 4th century that describes the work of a rhapsode, a performer of Homeric poetry. In his dialogue, the Ion, Plato has his rhapsode describe what he feels and sees when performing Homer:

Plato, Ion 535d-e

Ion: Now this proof is super clear to me, Socrates! I’ll tell you without hiding anything: whenever I say something pitiable [ἐλεεινόν τι], my eyes fill with tears. Whenever I say something frightening [φοβερὸν ἢ δεινόν], my hair stands straight up in fear and my heart leaps!

Socrates: What is this then, Ion? Should we say that a person is in their right mind when they are all dressed up in decorated finery and gold crowns at the sacrifices or the banquets and then, even though they haven’t lost anything, they are afraid still even though they stand among twenty thousand friendly people and there is no one attacking him or doing him wrong?

Ion: Well, by Zeus, not at all, Socrates, TBH.

Socrates: So you understand that you rhapsodes produce the same effects on most of your audiences?

Ion: Oh, yes I do! For I look down on them from the stage at each moment to see them crying and making terrible expressions [δεινὸν], awestruck [συνθαμβοῦντας] by what is said. I need to pay special attention to them since if I make them cry, then I get to laugh when I receive their money. But if I make them laugh, then I’ll cry over the money I’ve lost!”

Note how Ion uses language we see in the Iliad itself and the passage where Priam and Achilles meet. Where the internal evidence of epic shows its own audiences (the women, the old men, and Zeus) internalizing and responding to the narrative, Plato’s Ion features a performer expecting the same kinds of reactions from his audience (even if for less than noble reasons). When it comes to pity in particular, Emily Allen-Hornblower suggests that “The emotional charge that comes with the act of watching a loved one suffer (or die) is directly apparent in the phraseology of the Iliad...” (2015, 26) and suggests later that Achilles’ position as a spectator during most of the epic is an important part of his development. This provides, to me, another signal of what epic audiences were expected to be doing: watching, listening, feeling, and changing in turn.

My point here has a few parts: first, I think the Iliad expects people to respond to suffering with pity that reminds them of their own suffering; second, I think the epic models this process as something that is potentially humanizing, even if it is not necessarily so; third, I think the dramatic scope within the epic combined by some evidence for similar expectations outside the epic helps to support both a dynamic model of reading for Homer itself and also a shared performative ground for epic and ancient tragedy, helping to provide a different reason for why the Iliad is the most tragic of ancient epics.

A short bibliography

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Emily Allen-Hornblower, From agent to spectator : witnessing the aftermath in ancient Greek epic and tragedy, Trends in Classics. Supplementary Volumes, 30 (Berlin ; Boston (Mass.): De Gruyter, 2015).

Irene J. F. De Jong, ‘Homer : the first tragedian’, Greece and Rome, Ser. 2, 63.2 (2016) 149-162. Doi: 10[JC1] .1017/S0017383516000036

Hammer, Dean C.. “The « Iliad » as ethical thinking: politics, pity, and the operation of esteem.” Arethusa, vol. 35, no. 2, 2002, pp. 203-235.

Heiden, Bruce. “The simile of the fugitive homicide, Iliad 24.480-84: analogy, foiling, and allusion.” American Journal of Philology, vol. 119, no. 1, 1998, pp. 1-10.

Kim, Jinyo. 2000. The Pity of Achilles: Oral Style and the Unity of the Iliad. Rowman & Littlefield.

Glenn W. Most, ‘Anger and pity in Homer's « Iliad »’, Yale Classical Studies, 32. (2003) 50-75.

Rinon, Yoav. Homer and the dual model of the tragic. Ann Arbor (Mich.): University of Michigan Pr., 2008[JC2] .

Rutherford, Richard. “Tragic form and feeling in the Iliad.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. CII, 1982, pp. 145-160. Doi: 10.2307/631133

Marjolein Oele, ‘Suffering, pity and friendship: an Aristotelian reading of Book 24 of Homer’s « Iliad »’, Electronic Antiquity, 14.1 (2010-2011) 15.

Stroud, T. A., and Elizabeth Robertson. “Aristotle’s ‘Poetics’ and the Plot of the ‘Iliad.’” The Classical World 89, no. 3 (1996): 179–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/4351783.

Zanker, Graham. 1996. The Heart of Achilles: Characterization and Personal Ethics in the Iliad. University of Michigan.