This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 17 Here is a link to the overview of Iliad 16 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 17 of the Iliad is likely one of the most skimmed or skipped books in the reading of epic. And this is not because there is anything wrong with it! On the contrary, it is a masterpiece of expansion and suspense. I think it tends to get ignored because so much of what it does is keyed into the aesthetics of performance. The book starts with Menelas “not failing to notice the death of Patroklos” and centers around a struggle over his armor, and his body. But it also includes mourning immortal horses, Zeus inspiring a charioteer, Hektor and Aeneas chasing after horses, and Ajax defending Menelaos and Meriones as they carry Patroklos’ body away from the ships and Antilochus, Nestor’s son, rushes to tell Achilles what has happened. Book 18 starts with Achilles finding out what has happened.

At the end of book 15, the audience knows the plot of the rest of the epic. They know what will happen, but they don’t know how it will unfold. There are universes of stories to be told in the how of the events of the Iliad anticipated by Zeus: the deaths of Sarpedon, Patroklos, and Hektor could unfold in myriad ways and most audiences listening to the performance of the ‘rage of Achilles’ would know the basic plot details, but not the connective tissue between them. The 761 lines of book 17 create suspense for the audience as they await Achilles’ response, but at the same time they also provide opportunities to characterize the heroes in this specific telling of the epic and to engage with other narratives traditions. The plot of this book engages critically with the major themes I have noted to follow in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions, but the central themes I emphasize in reading and teaching book 17 are heroism, politics and Narrative Traditions.

Book 17, the Epic Cycle, and Neoanalysis

Let me start by talking about Narrative traditions. When I summarize book 17 above, I mention Menelaos, Hektor, Aeneas, and then Ajax and Antilochus. The collocation of characters here would, for many audiences, likely recall events from outside the Iliad as we know it, from narrative traditions authors like Proclus (in his Chrestomathia) and earlier scholars placed in the so-called epic cycle. As I have written about before, I think that the Epic Cycle is in many ways “a scholarly fiction.” It posits that there was a fixed group of poems that told the whole story of the Trojan War from beginning to end. I think that both the notion of telling the whole story and having one set of poems doing this work is out of touch with how performed songs worked in antiquity while also ignoring that there were many other narrative traditions that aren’t included in the small group of poems in the Trojan Cycle.

One of the reasons I am rather committed to this point of view has to do with what subsequent generations of scholars have done with the idea of the epic cycle, which is to reconstruct the content of the poems and then spend a good deal of time trying to figure out the relationship between such reconstructions and the poems we actually possess. This is dangerous in a few ways: First, almost everything we have about the so-called cycle has been preserved because of its similarity or relevance to our Homeric epics. So, we can’t trust that this material has been represented well or fully. Second, any speculation on the relationship between these reconstructions and the poems we have is complicated by the performance history of the narrative traditions that we have to try to separate from the fixed texts that have come down to us. Many different versions of the ‘rage of Achilles’ could have circulated in antiquity and influenced other poetic traditions, which in turn ended up influencing or shaping the Rage-song that survived for us.

(Elton Barker and I discuss a lot of this in our book Homer’s Thebes)

I don’t want to be dismissive of Neoanalysis entirely, however. Anyone who knows me as Homerist knows the approach gets under my skin, but I have tried to be fairer in years with what it can contribute. At its best–if it adopts a kind of epistemic humility about the actual relationship between texts we have and those we have reconstructed or lost–neoanalysis retains the ability to show us how complex the narrative backgrounds of the Iliad and the Odyssey are and how much our understanding of the poems can be enriched by thinking through these other traditions. This value is attenuated, however, by overly positivistic assertions that a specific passage in the Iliad or Odyssey was modeled on a specific moment in another poem. Such moves, I believe, underappreciate how many story traditions there were drawing on similar motifs while also failing to take into account the many possible versions of a given tradition. In addition, and this is probably what makes me the most irrational, such a positivistic approach also typically does not consider what audiences knew or could have known.

These considerations bear significantly on book 17 because it is possible to frame the book from its echoes of other narratives, foremost the struggle over Achilles’ body, rescued by Ajax, and, second, the relationship between Antilochus and Achilles in the Aithiopis. According to our ancient sources, the Aithiopis begins after the end of the Iliad and includes juicy details like Achilles allegedly falling in love with Penthesilea and killing her, only to kill Thersites too for accusing him of it. Then, Memnon, the son of Dawn, arrives to support the Trojans, kills Antilochus, which sends Achilles into another rage, that leads to him slaughtering Memnon. Once he has killed Memnon, Achilles pushes too far pursuing the Trojans into the city, and is killed by Apollo and Paris, near the very gate where Patroklos fell.

There are, from this summary, innumerable parallels between books 16 and 17 of the Iliad and the lost Aithiopis. I have shifted to the word “parallel” here instead of my usual “echo” or “resonance” because it is a visual metaphor, common in setting texts side-by-side. I am suspicious of taking such parallels too seriously because they are made up of the same very basic plot detail as Zeus’ outline of the events of the Iliad in book 15: they are just dots on a map, as yet unconnected by the detail that gives epic its force. Even if we assume that the plot of the lost Aithiopis has been faithfully transmitted and not ‘juiced’ or crafted to match the Iliad better, we have no way of knowing whether one poem or narrative tradition influenced the other and have not really developed the scholarly language to describe two closely related traditions influencing each other over time as their stories are told and retold and as they come in contact with other traditions.

We can say, I think, that the Iliad seems conscious of the importance of Antilochus and the basic details of his story (note how much he and Achilles engage in book 23, for example). We also know that the Odyssey is conscious of the fallout over the rescue of Achilles’ body and the awarding of his arms to Ajax instead of Odysseus. (Odysseus acts all surprised that Ajax won’t talk to him in the underworld!) But we can’t say with any confidence to what extent the Iliad we have relies on audience knowledge of the rescue of Achilles’ body in the drama of book 17.

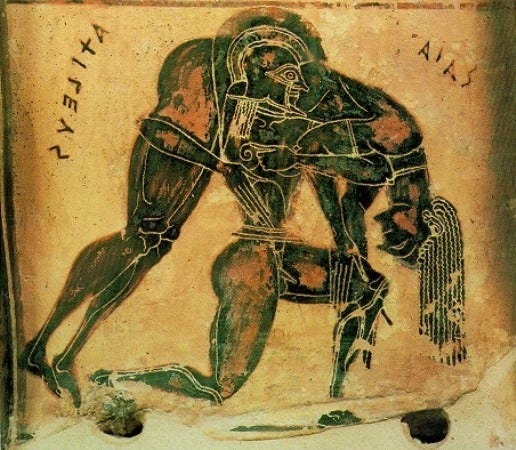

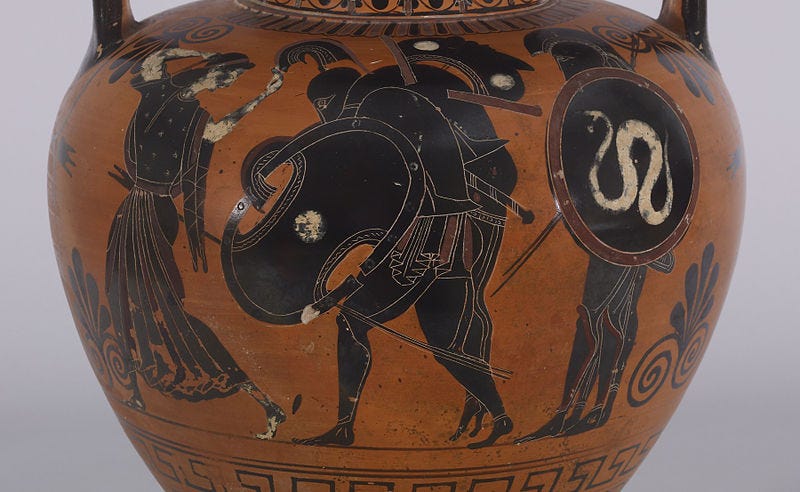

Book 17 works because of its detail, not because of its plot: the horses mourning, Menelaos striving, Hektor making some bad decisions, Glaukos laying into Hektor, the length of the expansion straining the suspension of our disbelief. All of these things put flesh on what would be pretty bare bones with just the basic outline of Achilles’ death. The rescue of Achilles’ body, indeed, was a popular motif, appearing in greek art well before the textualization of the Iliad as we know it. But it–and the judgment of the arms, and the rage of Achilles over Antilochus–all could have been episodes in a fluid and living oral tradition from which both the Iliad and the Aithiopis emerged.

(Provided, of course, we believe there was an Aithiopis with the scenes reported by Proclus, and that such summaries did not merely collocate all of the major episodes from the Trojan War later scholars dug up in order to tell the whole story.)

Some reading questions on book 17

Why is the Iliad a better epic with book 17 than without it?

What do Hektor’s actions in book 17 contribute to our understanding of his character?

Why does the narrative spend so much time on the struggle for Patroklos’ body?

A short Bibliography on the epic cycle and neoanalysis

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Barker, Elton T. E., and Joel P. Christensen. 2019. Homer's Thebes: Epic Rivalries and the Appropriation of Mythical Pasts. Hellenic Studies Series 84. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Degener, Michael. “Euphorbus’ plaint and plaits: the unsung valor of a foot soldier in Homer’s « Iliad ».” Phoenix, vol. 74, no. 3-4, 2020, pp. 220-243. Doi: 10.1353/phx.2020.0037

Fenno, Jonathan Brian. “The mist shed by Zeus in Iliad XVII.” The Classical Journal, vol. 104, no. 1, 2008-2009, pp. 1-9.

Harrison, E. L. “Homeric Wonder-Horses.” Hermes 119, no. 2 (1991): 252–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4476820.

Kozak, Lynn. “Character and context in the rebuke exchange of Iliad 17.142-184.” Classical World, vol. 106, no. 1, 2012-2013, pp. 1-14.

Moulton, C.. “The speech of Glaukos in Iliad 17.” Hermes, vol. CIX, 1981, pp. 1-8.

Neal, Tamara. “Blood and hunger in the « Iliad ».” Classical Philology, vol. 101, no. 1, 2006, pp. 15-33. Doi: 10.1086/505669

Schein, Seth L.. “The horses of Achilles in Book 17 of the « Iliad ».” « Epea pteroenta »: Beiträge zur Homerforschung : Festschrift für Wolfgang Kullmann zum 75. Geburtstag. Eds. Reichel, Michael and Rengakos, Antonios. Stuttgart: Steiner, 2002. 193-205.

West, M. L. “‘Iliad’ and ‘Aethiopis.’” The Classical Quarterly 53, no. 1 (2003): 1–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3556478.

A short Bibliography on the epic cycle and neoanalysis

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Arft, J., and J. M. Foley. 2015. “The Epic Cycle and Oral Tradition.” In Fantuzzi and Tsagalis, 78–95.

Barker, E.T.E. 2008. “ ‘Momos Advises Zeus’: The Changing Representations of Cypria Fragment One.” In Greece, Rome and the Near East, ed. E. Cingano and L. Milano, 33–73. Padova.

———. 2008. “Oedipus of Many Pains: Strategies of Contest in Homeric Poetry.”

Leeds International Classical Studies 7.2. (http://www.leeds.ac.uk/classiscs/lics/)

———. 2011. “On Not Remembering Tydeus: Diomedes and the Contest for Thebes.” Materiali e discussioni per l’analisi dei testi classici 66:9–44.

———. 2015. “Odysseus’ Nostos and the Odyssey’s Nostoi.” G. Philologia Antiqua

87–112.

Albertus Benarbé. Poetorum Epicorum Graecorum. Leipzig: Teubner, 1987.

Jonathan Burgess. The Tradition of the Trojan War in Homer and the Epic Cycle. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Cingano, E. 1992. “The Death of Oedipus in the Epic Tradition.” Phoenix 46:1–11.

———. 2000. “Tradizioni su Tebe nell’epica e nella lirica greca arcaica.” In La città

di Argo: Mito, storia, tradizioni poetiche, ed. P. A. Bernardini, 59–68. Rome.

———. 2004. “The Sacrificial Cut and the Sense of Honour Wronged in Greek

Joel Christensen. “Revising Athena’s Rage: Kassandra and the Homeric Appropriation of Nostos.” YAGE 3: 88–116.

Malcolm Davies. Epicorum Graecorum Fragmenta. Göttingen : Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, 1988.

Malcolm Davies. The Greek Epic Cycle. London: Bristol, 1989.

Fantuzzi, M., and C. Tsagalis, eds. 2014. The Greek Epic Cycle and its Ancient Reception: A Companion. Cambridge.

Margalit Finkelberg. The Cypria, the Iliad, and the Problem of Multiformity in Oral and Written Tradition, ‹‹CP›› 95, 2000, pp. 1-11.

Lulli, L. 2014. “Local Epics and Epic Cycles: The Anomalous Case of a Submerged Genre.” In Submerged Literature in Ancient Greek Culture, ed. G. Colesanti and Giordano, 76–90. Berlin and Boston.

L. Huxley. Greek Epic Poetry from Eumelos to Panyassis, Cambridge 1969.

Richard Martin. Telemachus and the Last Hero Song, ‹‹Colby Quarterly›› 29, 1993, pp. 222-240.

Jasper Griffin. “The epic cycle and the uniqueness of Homer.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 97 (1977) 39-53.

Ingrid Holmberg “The Creation of the Ancient Greek Epic Cycle”

Marks, J., ‘‘Alternative Odysseys: The Case of Thoas and Odysseus’’, TAPhA 133.2 (2003) 209-226.

Gregory Nagy. The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek poetry. Baltimore 1999.

Nagy, G., “Oral Traditions, Written Texts, and Questions of Authorship”, in: M. Fantuzzi / C. Tsagalis (eds.), Cambridge Companion to the Greek Epic Cycle, Cambridge 2015, 59-77.

Nelson, T. J., ‘‘Intertextual Agōnes in Archaic Greek Epic: Penelope vs. the Catalogue of Women’’, YAGE 5.1 (2021) 25-57.

Rutherford, I., “The Catalogue of Women within the Greek Epic Tradition: Allusion, Intertextuality and Traditional Referentiality”, in: O. Anderson / D. T. T. Haug (eds.), Relative Chronology of Early Greek Epic Poetry, Cambridge 2012, 152-167.

Albert Severyns. Le cycle épique dans l’école d’Aristarque. Paris: Les Belles Lettres 1928.

Albert Severyns. Recherches sur la Chrestomathie de Proclos. Paris: Faculté de Philosophie et Lettres, Liége, 1938.

Giampiero Scafoglio. La questione ciclica, ‹‹RPh››78, 2004, pp. 289-310.

Laura Slatkin. The Power of Thetis: Allusion and Interpretation in the Iliad. Berkeley 1991.

Michael Squire. The Iliad in a Nutshell: Visualizing Epic on the Tabulae Iliacae. Oxford: 2011.

Tsagalis, C., Early Greek Epic Fragments I: Antiquarian and Genealogical Epic, Berlin / Boston 2017.

Marco Fantuzzi and Christos Tsagalis. “Introduction: Kyklos, Epic Cycle, and Cyclic Poetry.” In M. Fantuzzi and C. Tsagalis (eds.). ACompanion to the Greek Epic Cycle and Its Fortune in the Ancient World. (Brill, 2014).

Martin L. West. The Epic Cycle: A Commentary on the Lost Troy Epics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Interested to read your thoughts. The question of when the story of Achilles' wrath reached this overall form, more or less the question of its unity, is of course fairly basic to assessing questions of parallel narratives. I happen to think there's good evidence to suggest the narratives of both Homeric poems ought to have come into focus already in the BA (or its immediate aftermath), which tends to make me a bit more skeptical of some recent neoanalytical approaches.

-Michael Clark