This post is a basic introduction to reading Iliad 23. Here is a link to the overview of Iliad 22 and another to the plan in general. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Book 23 of the Iliad provides a break in the relentless action following Achilles’ return. It is entirely dedicated to the honoring of Patroklos, both through his burial and the funeral games in his honor. But I suspect that many audiences miss out on the sustained rituals for Patroklos because the games become such an engrossing distraction. The book starts with a reminder that Patroklos remains unburied (through a conversation with a ghost!), then moves through the preparations for his cremation and burial, and then proceeds through a long series of athletic contests in his honor. Along the way, we have some human sacrifice when Achilles kills the twelve Trojan youths he selected in book 21 to slaughter over Patroklos’ pyre.

Iliad 23 is actually anything but fun and games, even if it appears to be a bit of a diversion (or what some have dismissed as a “mere interlude”). The burial is an important part of heroic honors for the dead, yet is marked by a strange sacrifice and the ongoing mutilation of Hektor’s corpse; the games echo the political questions of Iliad 1, 2, 9, and 19; and the funeral games themselves may also be engaging with traditions both of the death of Patroklos outside the Iliad and of the games that were held following Achilles’ death. As such, each of part the book adds something to the themes I have outlined in reading the Iliad: (1) Politics, (2) Heroism; (3) Gods and Humans; (4) Family & Friends; (5) Narrative Traditions. Among these, however, I think book 21 speaks most directly to politics, heroism, and narrative traditions.

Contextualizing the Funeral Games

Funeral games are an important context in Greek narrative from myths around the foundation of the four major Panhellenic contests (Olympian, Nemean, Pythian, and Isthmian games) to providing settings and inflection points for myths in general.. Funeral games feature in narrative traditions around Thebes (especially Oedipus and Laius) and Pelias (which leads to the voyage of Jason and the Argonauts) and extend to less well-known traditions like those of Erginos of Orchomenos. Of course, by the classical age, games had become a significant ritualized part of aristocratic culture in Greece.

It is that groundedness of athletic contests in elite/aristocratic culture that can provide some perspective for modern audiences to understand how ancient audiences saw games in the Homeric epics. In the Archaic and Classical periods, Panhellenic games developed as the context for aristocrats from individual city states to compete against each other outside of war, to assert/establish their worth vis a vis their peers (for themselves and for people back in their cities), and to explore a shared elite culture across city-boundaries. Athletic competitions are the kinds of things that ‘heroes’ do when they aren’t in war or some civil conflict.

There’s some disagreement about how much of what is represented would have been at home in the world of Homeric audiences. Ioannis Mouratidis suggests that the Iliad includes material from the oral tradition going all the way back to the Mycenaen age but including elements through the Archaic age as well, reflecting the movement from an autocratic model to the city-state that shaped the perspectives of most ancient audiences. Jonas Grethlein adds to this the recognition that the burial and the games are ritual acts too---as such, they are doubly removed from political ‘reality’ but serve even more as a metanarrative device, another mirror to allow internal and external audiences to work through interpretations of the epic.

As such, games in ancient Greek culture and in Homeric epic are never just play—they are opportunities to create and establish individual identities in a competitive yet not destructive context. Within Homer, then, the games provide a familiar, albeit likely still fantastic, context for ancient audiences while also offering a context for participants in epic to revisit the political rancor of book 1. As William Scott (1997) notes, the games create a cooperative atmosphere where Achilles is in charge to enforce a particular order of games and of valuing other people. In its structures and discussions, however, it corresponds both to the break of Iliad 1 and the reunification of the Achaean assembly in book 2 (As Richardson points out [1993, 164-6]. Cf. Whitman 1958, 261-4). As several scholars have point out, there is a close connection between the institutional structure of the assembly throughout the Iliad and context of the Funeral Games. See, for example, Wilson 2002, 57 and Hammer 2002, 134ff. Deborah Beck (2005, 233-41) makes explicit the connection between the Achaean assembly and the funeral games.

The games function both as a space for re-imagining politics and for putting Achilles in a position to lead. For the former, Hammer offers five reasons for this (Hammer 1997, 14-16; cf. Ulf 2004.): (1) The burial rites are performed by the Achaeans as a community; (2) The subsequent games performed at the gravesite of a dead hero evokes cult-hero practices; (3) Public challenges regarding prize distribution are offered and answered; (4) Formal procedures for adjudicating disputes appear; and (5) Zeus is invoked as a guarantor of distribution in a different way. Good analyses of the games (see below) look at the way the disputes between characters are played out, the language they use, and what happens when someone intervenes or mediates.

While some see Iliad 23 as a collective effort to reimagine Greek political activity (see, e.g. Donlan 1979), many others have seen the games as being particular to Achilles’ efforts to rethink and rework the events that dominated the epic’s beginning. Kenneth Kitchell (1998) argues that Achilles’ settlement of the disputes in the games as well as his treatment of the wrestling match and spear-contest illustrate his profound character change while Oliver Taplin has suggested that “one of the main poetic functions of the funeral games [is] to show Achilles soothing and resolving public strife, instead of provoking and furthering it” (1992, 253). Recently, Adrian Kelly has emphasized that the funeral games are the last opportunity for Achilles to demonstrate excellence in speaking and action, straining for that heroic ideal of surpassing everyone. And the results, according to Kelly, are mixed: “It is entirely fitting, then, that Achilles’ arbitrations in the Funeral Games show his shortcomings, and his exceptionalism, all too clearly, both in terms of what he does and what others achieve without him” (108).

As I will discuss in one of the subsequent posts about this book, the funeral games for Patroklos are a fantasy of political redistribution that help audiences think through just how difficult it is to resolve the tensions left over from book 1. If they demonstrate anything, it is that maintaining a status quo without coercive violence is hard work, but perhaps a more possible goal than a world where everyone is valued as they think they should be.

Reading Questions for book 23

How does the conversation with Patroklos’ ghost shape our understanding of his relationship with Achilles?

How does Achilles run the funerary games?

How do the debates in the games reflect/refract the conflicts of book 1

Short bibliography on the Funeral games

n.b this is not an exhaustive bibliography. If you’d like anything else included, please let me know.

Deborah Beck. Homeric Conversation. Washington, D.C.: Center for Hellenic Studies, 2005.

Walter Donlan. “The Structure of Authority in the Iliad.” Arethusa 12 (1979) 51-70.

Dunkle, Roger. “Nestor, Odysseus, and the μῆτις-βίη antithesis. The funeral games, Iliad 23.” Classical World, vol. LXXXI, 1987, pp. 1-17.

Ellsworth, J. D.. “Ἀγων νεῶν. An unrecognized metaphor in the Iliad.” Classical Philology, vol. LXIX, 1974, pp. 258-264.

Elmer, D.F. (2013). The Poetics of Consent: Collective Decision Making and the Iliad. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press., https://doi.org/10.1353/book.21075.

Garland, R.S.J. “‘GERAS THANONTON’: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE CLAIMS OF THE HOMERIC DEAD.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, no. 29 (1982): 69–80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43646122.

Grethlein, Jonas. “Epic narrative and ritual: the case of the funeral games in Iliad 23.” Literatur und Religion: Wege zu einer mythisch-rituellen Poetik bei den Griechen. Eds. Bierl, Anton, Lämmle, Rebecca and Wesselmann, Katharina. MythosEikonPoiesis; 1.1-2. Berlin ; New York: De Gruyter, 2007. 151-177.

Dean Hammer.“ ‘Who Shall Readily Obey?” Authority and Politics in the Iliad.” Phoenix 51 (1997) 1-24.

Kelly, Adrian. “Achilles in control ? : managing oneself and others in the Funeral Games.” Conflict and consensus in early Greek hexameter poetry. Eds. Bassino, Paola, Canevaro, Lilah Grace and Graziosi, Barbara. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pr., 2017. 87-108. Doi: 10.1017/9781316800034.005

Kenneth F. Kitchell. “‘But the mare I will not give up’: The Games in Iliad 23.” The Classical Bulletin 74 (1998) 159-71.

Mouratidis, Ioannis. “Anachronism in the Homeric games and sports.” Nikephoros, vol. III, 1990, pp. 11-22.

Mylonas, George E. “Homeric and Mycenaean Burial Customs.” American Journal of Archaeology 52, no. 1 (1948): 56–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/500553.

Rengakos, Antonios. “Aethiopis.” The Greek Epic Cycle and its ancient reception : a companion. Eds. Fantuzzi, Marco and Tsagalis, Christos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pr., 2015. 306-317.

Nicholas Richardson. The Iliad: A Commentary. Volume VI: Books 21-24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Roller, Lynn E. “Funeral Games in Greek Art.” American Journal of Archaeology 85, no. 2 (1981): 107–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/505030.

Scott, William C.. “The etiquette of games in Iliad 23.” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, vol. 38, no. 3, 1997, pp. 213-227.

H. A. Shapiro, Mario Iozzo, Adrienne Lezzi-Hafter, The François Vase: New Perspectives (2 vols.). Akanthus proceedings 3. Kilchberg, Zurich: Akanthus, 2013. 192; 7, 47 p. of plates.

Oliver Taplin. Homeric Soundings: The Shape of the Iliad. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Christoph Ulf. “Iliad 23: die Bestattung des Patroklos und das Sportfest der “Patroklos-Spiele”: zwei Teile einer mirror-story.” in Herbert Heftner and Hurt Tomaschitz (eds.). Ad Fontes! Festschrift für Gerhard Dobesch zum 65 Geburtstag am 15. September 2004. Wien: Phoibos, 2004, 73-86.

Cedric Hubbell Whitman. Homer and the Heroic Tradition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Malcolm M. Willcock, ‘The funeral games of Patroclus’, Proceedings of the Classical Association, LXX. (1973) 36.

Donna F. Wilson. Ransom, Revenge, and Heroic Identity in the Iliad. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

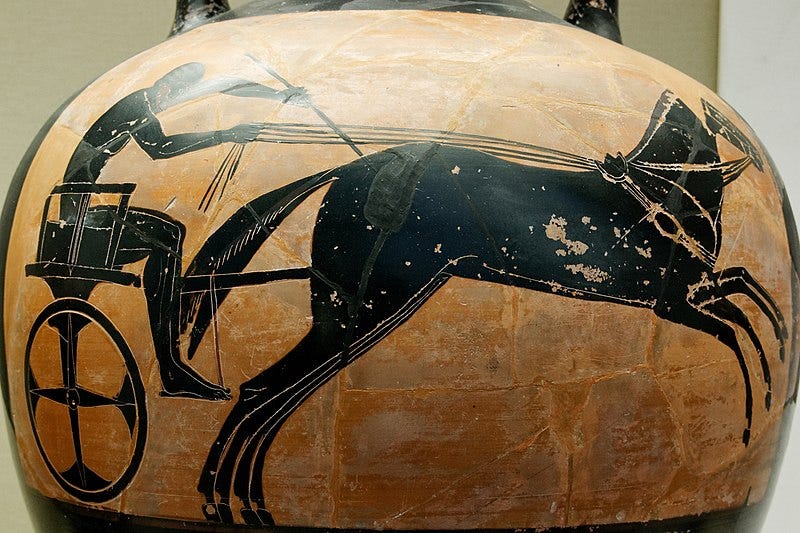

Here’s an image

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kleitias_e_vasaio_ergotimos,_cratere_fran%C3%A7ois,_570_ac_ca._giochi_funebri_per_patroclo_02.JPG