This is the final post dedicated to Iliad 24. As a reminder, these posts will remain free, but there is an option to be a financial supporter. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

The Iliad begins:

“Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles”

Μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω ᾿Αχιλῆος

And then it ends:

“And so they were completing the burial of Hektor, tamer of horses”

῝Ως οἵ γ' ἀμφίεπον τάφον ῞Εκτορος ἱπποδάμοιο

Imagine if all we had of the poem was a scholarly record conveying these two lines. What would we make of the journey that we would have to take to get from line 1 to line 2? How would we relate the opening request with the final fact and then connect these in turn to a larger tradition of myth? One might naturally assume that the former leads to the latter in a causal fashion, but there’s no necessary reason to posit that.

There’s an openness, though, to both lines. The initial invocation asks for a story to be told; the final one offers a scene in process: the imperfect tense of the verb ἀμφίεπον shows an action that is ongoing but not yet complete, it leaves the audience with the sense that more is still to come, that the final word has not actually been spoken. This certainly functions to mark the epic as part of a larger story cycle, just as the imperfect in line 1.7 (Διὸς δ' ἐτελείετο βουλή) indicates that the Iliad is part of a larger process, a cosmic narrative arc.

Yet, without external evidence, each name is merely an empty sign waiting to be filled, a story needing to be told. But we have the whole poem. We can follow from line 1.1 to 24.804. And we still likely ask why the Iliad ends with the burial of Hektor, tamer of horses. Ancient scholars had a range of less than satisfactory answers. The scholia record that a scholar named Menekrates believed that Homer was silent about the events after Hektor because “he sensed his own weakness and inability to tell the events in the same way” (Schol. bT ad. Hom. Il. 21.804). Another claims that some modified the final line:

Schol. T ad. Hom. Il. 21.804a

“Some people write “and so they were completing the burial of Hektor. Then the Amazon came / the daughter of Ares, the great-hearted man-killer”

τινὲς γράφουσιν „ὣς οἵ γ’ ἀμφίεπον τάφον ῞Εκτορος· ἦλθε δ’ ᾿Αμαζών, / ῎Αρηος θυγάτηρ μεγαλήτορος ἀνδροφόνοιο” (804. 804a).

In this version, we find the possibility of an ever-expanding tale, moving from the Iliad to the events of the Aithiopis without much of a break at all. While I have no doubt that ancient performances offered such opportunities for stitching and re-stitching narratives together, I think we still need to contend with the beginning, middle, and end of our Iliad. Even if a performer would segue from an Iliad to an Aithiopis, we still face the fact that each was felt to be a unitary and individualizable narrative. So, here are some other reasons why the Iliad ends as it does.

1.‘Epic’ time is different from normal narrative time: it is more like a time loop in modern science fiction. All the main events always happen and have already always happened, but there’s room for variation in the journey between them. This occupies a place between what we might clumsily call “ritual time” and a causal narrative chain. For the former, I have in mind the narrative cycle of a liturgical calendar where congregants/audiences are treated to the same stories at the same part of the year. The stories never change because they have happened and must happen the same, but our experiences of them change as we move from one repetition to another. For the latter, the logic of causation is imposed through the repetition of the same basic events, but by finding space in the interstices to tell different stories, audiences explore the dynamic interaction between determinism and agency, between accepting what one cannot change and being empowered to alter what one can.

2.The city has already been destroyed in the imaginations of the characters and the audience. Following on the immutable layering of epic time, Iliadic narrative refers to canonical events of the Trojan War but mostly moves around them: the judgment of Paris, the abduction of Helen, the marshaling of the armies, the sacrifice of Iphigenia, the sack of the city, and other events all exist on the periphery, at times marginalized to such an extent that scholars can doubt whether or not the Homeric epics appeal to them. At the same time, the Iliad appropriates and reperforms moments from the larger tale that should not be part if its tale, engaging in a creative anachronism that manages to place the catalogue of ships, the teikhoskopia, the duel over Helen, and the building of Achaean fortifications between Achilles’ falling out with Agamemnon and the embassy to try to resolve the spat.

The Iliad reshuffles the deck of mythical time both to assert the supremacy of its story and to show that no series of events, no causal chain, can alter the outcome of the overall narrative. This is theological in the cosmic sense: notions like Zeus’ plan and the double determination (when the narrative shows the gods ‘causing’ an action but also features mortals choosing to act without knowledge of divine will) underscores the complexity of causation and the inscrutability of single efficient causes. At the same time, such shuffling is evocative of human cognition, the way we understand and retain basic concepts of beginning and ending but can lose track of intermediary steps.

3.Achilles has already died. In a way, this is no different than the previous point, but it is important enough to emphasize again. The Iliad does not merely deal out the deck of myth in a different order, it redraws the images on the most important cards to achieve similar ends. Achilles dies through Patroklos—his physical death is disassembled and re-used in book 11 and then book 16, anticipated in books 18, 19, 22, 23, and 24, but never performed because it has already been achieved. Just as the city is destroyed in the words of Hektor, Andromache, Priam, and Hecuba, so too is Achilles’ death portrayed through Patroklos’ surrogacy and the divine and mortal speeches that anticipate it.

4.Hektor’s death may be more important than Achilles’. As I have mentioned before, the Iliad takes part in an etiological (that is, explanatory) arc that moves from the dios boulê, Zeus’ plan to rid the world of the race of heroes, to an era when the realms of gods and men are more thoroughly distinct. While the Odyssey more-or-less completes this journey toward Hesiod’s Works and Days, where human beings toil distant from tangible divine favor or aid, the Iliad moves audiences from the twin rages of Achilles and Apollo in book 1 (where they are both upset at Agamemnon) to Apollo’s anger at Achilles for his treatment of Hektor in book 24. Apollo—much to Hera’s surprise—takes the side of a non-divine mortal for the rite of burial against one closer to his own kin.

Along the way, we see the widening distance between divine knowledge and human knowledge—the whole motif of double determination, whereby we as audience members see the gods and mortals as understanding different levels of causation for a given action. The repeated toggling between divine intervention paired with human decisions shows us separate worlds, even separate realities or dimensions whose entanglement does little more than increase damage and pain to one another. It is almost as if the Iliad attests to a time when the fabric between two different realities was thin enough to be permeable and that it shows us how perilous it is when beings from one realm meddle with events in another. The world of the gods was overturned by the silly decision of one man (Paris!); the mortal plain roils with each outsized, overwrought divine act. The steady movement towards emphasizing the honor of mortals in death and the separation of gods and humans both justifies and supports the way the world is for mortals and suggests rather strongly that it is better this way.

5.Hektor’s burial is the end of an era. And also a beginning. Hektor is different from Achilles as a full-mortal and as a ‘family’ man. By ending with his burial rather than the fall of the city or the funeral games for Achilles, the Iliad elevates his importance and closes out the race of heroes by encapsulating a different series of values in this one fallible man. Hektor is far from perfect throughout the epic: he struggles to understand his role in leading the city, he blusters and glowers when things don’t go his way, and he is shown to be in the framework of Achilles and Diomedes somewhat un-heroic in his final moments. But the laments that follow his death in books 22 and 24—cast against the obscenity of Achilles’ treatment of his body—double down on the importance of his unheroic character as a son, father, and a man whose kindness towards the most hated woman in the world and the cause of all his troubles is so incredible that scholars have speculated he was under the spell of her charisma. Hektor’s inconsistencies and internal contradictions form a counterpoint to Achilles’. In a universe where even the gods are churlish and quick-to-rage, what kinds of excess should we be grateful for in a man?

6.Hektor’s burial may also be self-reflective for epic poetry. As I mentioned above, the tense/aspect of the verb performing Hektor’s burial is incomplete, and ongoing (῝Ως οἵ γ' ἀμφίεπον τάφον ῞Εκτορος ἱπποδάμοιο). The Iliad doesn’t so much end as fade away, to black as in the end of the final episode of the Sopranos. The process of burying Hektor remains ongoing as the poem ends, as we all continue to engage in its continuation through sharing in his memory. But I think the process, the imperfectivity goes farther than this.

The process of the burial is the beginning of enshrining Hektor’s memory and creating his kleos. But this may also be an example of an unnoticed ekphrasis. While the tomb itself is not the creation of a work of art like Achilles’ shield, it is still the execution of a physical craft described within an oral/written artform. As such it may contain an implicit comparison between the practice of burial and the art of epic poetry.

Homer, Il. 24.797–800

“They quickly placed the bones in an empty trench and then

They covered it with great, well-fitted stones.

They rushed to heap up a marker, around which they set guards

In case the well-greaved Achaeans should attack too soon.”αἶψα δ' ἄρ' ἐς κοίλην κάπετον θέσαν, αὐτὰρ ὕπερθε

πυκνοῖσιν λάεσσι κατεστόρεσαν μεγάλοισι·

ῥίμφα δὲ σῆμ' ἔχεαν, περὶ δὲ σκοποὶ ἥατο πάντῃ,

μὴ πρὶν ἐφορμηθεῖεν ἐϋκνήμιδες ᾿Αχαιοί.

In Iliad seven, Hector challenges the ‘best of the Achaeans’ to a duel. There he imagines that, once he had won the contest, the dead hero’s tomb would be a monument to, and sign of, his everlasting glory. Ironically, the dead hero’s tomb turns out to be his, once the Trojans construct it at the epic's end

But what kind of sign is it? Homer describes how the Trojans’ burial mound for Hector leaves ‘a mark’—the word here is sêma (from which we get the words ‘semantics’ or ‘semaphore’), and also means a sign or symbol. In the end, then, the epic leaves us with a symbol of some kind that I think points back to this epic itself. Ostensibly, of course, that is Hector’s burial mound, a physical marker of his fame—and as a metonym it stands for the fame of all the heroes who fought at Troy. Yet, its immediate referent, the physical thing it describes, is a ‘hollow grave’ (koilên kapeton).

An English speaker might wonder whether or not the hollowness of the grave marks some sort of empty meaning and thus offers some judgment on the vanity and meaninglessness of the conflict, perhaps evoking ambivalence. But part of the trick in translating metaphors from one culture to another is understanding that a cognitive valence can be very different. In English, ‘hollow’ and ‘empty’ tend to refer to the absence of substance within something else. (Hence, our use for it to describe depression or anhedonia.)

But in ancient Greek, the word koilê is used to describe the shape made by a thing that allows it to hold something else. It can sometimes then come to shift to point to the absence of that something else, but it is, more often, a marker for the vessel which can carry something, even when it is carrying it. In conjunction with Hektor’s grave, consider the following lyric mentions of the ‘hollow ships’ of the Trojan War:

Consider:

Ibycus fr. 1a 16-19

Nor yet the overreaching virtue

of heroes whom the hollow,

many-benched ships brought

as the destruction of Troy.ἡρ]ώων ἀρετὰν

ὑπ]εράφανον οὕς τε κοίλα[ι

νᾶες] πολυγόμφοι ἐλεύσα[ν

Τροί]αι κακόν, ἥρωας ἐσ̣θ̣[λούς·

Pindar, Ol. 6.1

Unrisked virtue becomes honored

Neither among men nor in the empty ships.

But many a man is remembered

When something noble has been tried.… ἀκίνδυνοι δ' ἀρεταί

οὔτε παρ' ἀνδράσιν οὔτ' ἐν ναυσὶ κοίλαις

τίμιαι· πολλοὶ δὲ μέμναν-

ται, καλὸν εἴ τι ποναθῇ.

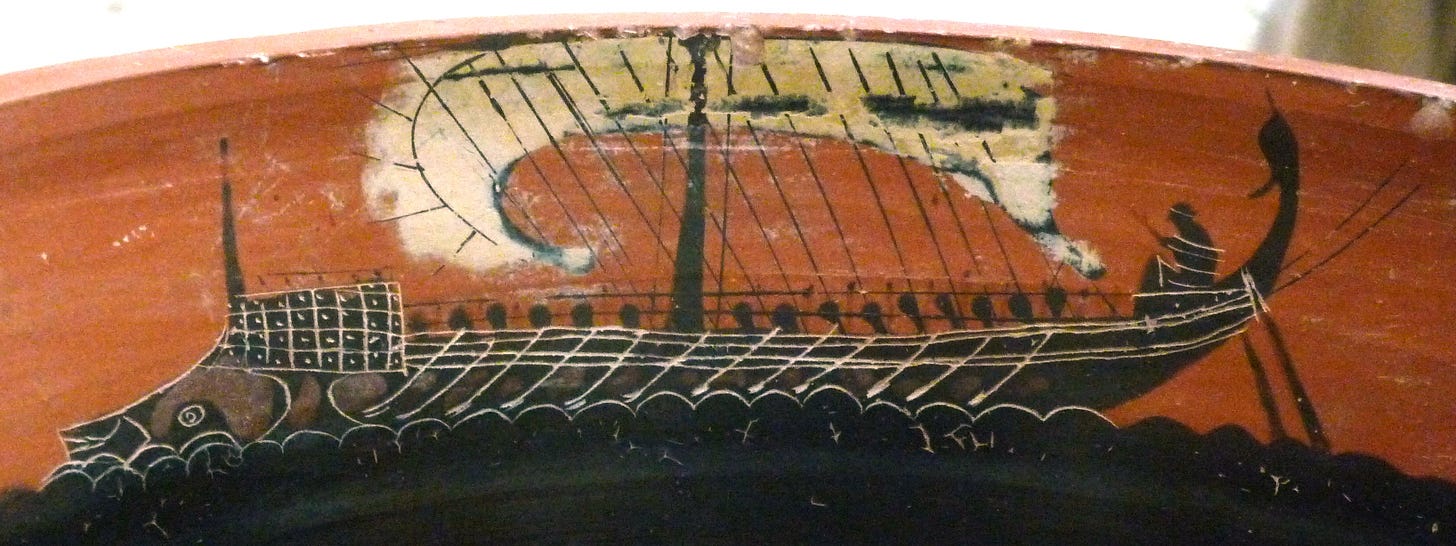

In both these passages, the ships are marked out for their potential to carry something and their ability to do so. It is also arguable that the ships carry ethical content of the heroes they convey to Troy as well. Of course, in the Iliad the ships are often invoked as empty in their capacity to carry things as well as people—but these moments are also seen as critical in telling the story, as when the Trojan herald Idaios refers to the beginning of the conflict:

Homer, Il. 7.399-400

“However many possessions Alexandros led in his hollow ships

To troy. Oh, how I wish he had died first!”κτήματα μὲν ὅσ' ᾿Αλέξανδρος κοίλῃς ἐνὶ νηυσὶν

ἠγάγετο Τροίηνδ'· ὡς πρὶν ὤφελλ' ἀπολέσθαι·

So, when the word used to describe that ‘hollow trench’ (koilein kápeton) is the same used for the ships that brought the Achaeans to Troy and will take their stories away, the grave is being marked out as a vessel for Hector’s fame. The message of Hektor’s “empty grave” is not like the elegiac regret of T.S. Eliot’s “Hollow Men”, but instead it represents the potential of an empty vessel to be filled by the audience in its reception of the poem. It is a signal, I think, of the assumption that meaning continues to be made outside the world of the poem and that we stare into the sign we create the meaning based on what we ‘read’ there and knew before. Each time we engage in this process, we create anew. This outward looking burial mound that is simultaneously Hektor’s grave and the Iliad itself is a continuation of the narrative’s strategy of showing us characters responding to other’s narratives by reflecting on their own lives and then engaging in storytelling themselves, as we see in Achilles’ final story to Priam in book 24. We are the people to come, walking or sailing by on the Hellespont or traveling through the tale as it is sung or read. We recreate the story of Achilles, bound up in the grave of the man he killed, just as Hektor imagined his story would be told through his own enemy’s tomb.

So, in addition to Hector’s grave, this vessel, this sêma, refers to the Iliad itself. The epic is a vessel of fame, of Hector’s, Achilles’, and Agamemnon’s, but it is also a marker for the death of a world, for the end of a bygone time. On the one hand, it marks the transition from the heroic age to the present day. On the other, it acts as a grave marker of an entire tradition of epic poetry which would have sung about the wars at Troy and Thebes. We as audience members recreate the tale, but in the raiment of our time, transforming it, but reviving it too.

The hollowness of this thing is not about being empty, but about having the power to carry something, to produce something else, even something new. As the Tao Te Ching states, “We shape clay into a pot / but it is the emptiness inside / that holds whatever we want. We hammer wood for a house, but it is the inner space / that makes it livable” (Chapter 11; Stephen Mitchell, 1988). Thus, Hector’s grave carries with it everything he was or could be; and the Iliad, far from empty and devoid of meaning, is that vessel that carries so much unknown across the oceans of time.

Tao Te Ching: Chapter 11

translated by Stephen Mitchell (1988)

We join spokes together in a wheel,

but it is the center hole

that makes the wagon move.We shape clay into a pot,

but it is the emptiness inside

that holds whatever we want.We hammer wood for a house,

but it is the inner space

that makes it livable.We work with being

but non-being is what we use.