This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

Homer, Iliad 3.1-8

“But when each of them were lined up with their leaders,

The Trojans went forward with screeching and cries just like birds,

With the sound like the call of cranes near the sky,

Those birds that flee the winter and its endless rain

And fly with a cry over the ocean’s streams

Bringing death and murder to the Pygmies.

The Achaeans went forward exhaling rage in silence,

Eager in their heart to stand in defense of one another.”Αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ κόσμηθεν ἅμ' ἡγεμόνεσσιν ἕκαστοι,

Τρῶες μὲν κλαγγῇ τ' ἐνοπῇ τ' ἴσαν ὄρνιθες ὣς

ἠΰτε περ κλαγγὴ γεράνων πέλει οὐρανόθι πρό·

αἵ τ' ἐπεὶ οὖν χειμῶνα φύγον καὶ ἀθέσφατον ὄμβρον

corr. κλαγγῇ ταί γε πέτονται ἐπ' ὠκεανοῖο ῥοάων

corr. ἀνδράσι Πυγμαίοισι φόνον καὶ κῆρα φέρουσαι·

ἠέριαι δ' ἄρα ταί γε κακὴν ἔριδα προφέρονται.

οἳ δ' ἄρ' ἴσαν σιγῇ μένεα πνείοντες ᾿Αχαιοὶ

ἐν θυμῷ μεμαῶτες ἀλεξέμεν ἀλλήλοισιν.

This opening simile offers a somewhat surprising transition from the catalogs that end book 2 on the way to the action of book three. As I discuss in earlier posts about book 3, it is a fascinating book that continues some of the themes and concerns that emerge in book 2: a (re)introduction of the Trojans (starting with their catalog) and a (re)starting of the Trojan War. In my reading of the way the Iliad works as a coherent narrative that engages with and communicates the larger interest of both the Trojan War and the tradition of epic performance, book 3 presents episodes that evoke the character of the war’s beginning while still working within the narrative arc of the story of the rage of Achilles

1-111 Beginning, Proposal of a Dual [request for Priam to be fetched]

112-263 Teikhoskopia (“viewing from the walls”): Helen describes the Greeks

264-376 Duel

377-461 Aphrodite and the Reunion of Helen and Paris

The sequence of events laid as laid out here takes the audience almost in reverse from the war to the meeting of Helen and Paris. One could imagine the debate between Helen and Aphrodite and Helen’s begrudging acceptance of Paris as the Iliad’s take on blaming Helen, Paris’ character, and the shared conspiracy of divine will and human frailty. In this, the book offers one narrative arc that begins with Hektor upbraiding and shaming his brother and ends with Paris’ rather pathetic “aw shucks” return to the scene of their ‘crime’ (i.e., the bedroom). At the same time, if we think about the wide angle lens approach, this arc also allows us an early meeting between Menelaos and Priam and a view of the Greeks from the Trojans’ perspective. Book 3 situates the audience in space between Troy and the Greeks (anticipating book 6 in a way) and while also integrating potentially ‘famous’ episodes from the fuller war into its narrative.

Given these primary functions of book 3, what sense can we make of the opening simile? It compares the sound of the assembled Trojan armies (and their allies) to the cry of migratory cranes who bring “death and doom to the Pygmies” during the winter. A simple reading of the simile might see the Trojans as moving away from their home and bringing death to the Greeks. For moving us into the action, this interpretation suffices, but I don’t think it is enough.

Fortunately, two of my favorite pieces of Homeric scholarship address this passage and in very different ways. Hilary Mackie, in her Talking Trojan: Speech and Community in the Iliad (1996), opens with this simile to suggest that unlike the Achaeans, the Trojan use of language “suggest[s] a lack of social order” (14). She contrasts the depiction of the Greeks following the simile as one of cohesion (16) and recalls the similes from book two that marks the Achaeans in mutiny or chaos as resolving into an eventual reimposition of order through the scapegoating of Thersites (17). Mackie relates this passage to the assertion from book 2 that the Trojans and their allies have many different languages (2.802-806) and for that reason must rely on captains to command only their own troops (19). She concludes that this passage extends a process of “underselling the Trojan army” (21) and suggests “when the Trojans march out at the beginning of Book 3, they are still dominated by undifferentiated clamor (klaggê). With their mixed languages, the Trojans cannot function as an articulate group.

I have always appreciated this argument insofar as it helps modern audiences understand differences between Trojan and Achaean politics (something Mackie also goes on to discuss). But I do worry if this interpretation against a linguistic pluralism may lean too much into the Iliad’s own attempt to downplay the strength of the Trojans (who have managed to hold the mighty Achaeans off for ten years!). I fear, in addition, that some might misinterpret such an argument as implying that the Iliad is essentially against heterogeneity. (And I don’t think this is Mackie’s argument at all. See Shawn Ross’ paper on language and Panhellenism in the Iliad for a perspective from contemporary audiences.)

The other example of Homeric scholarship that engages with this opening is Leonard Muellner’s “The Simile of the Cranes and Pygmies”. I am deeply fond of this article because my first Greek teacher and many decade mentor and friend, Lenny, wrote it; but beyond that, it is one of the finest works on Homeric similes from the 20th century. Lenny uses this article to argue both that similes are not less traditional than other parts of Homeric epic (contra someone like Shipp or others who claim similes are ‘later’ than other parts of the Iliad or Odyssey) and also to show how a ‘device’ like this “continually enhances and preserves the epic's expressive and evocative power” (61).

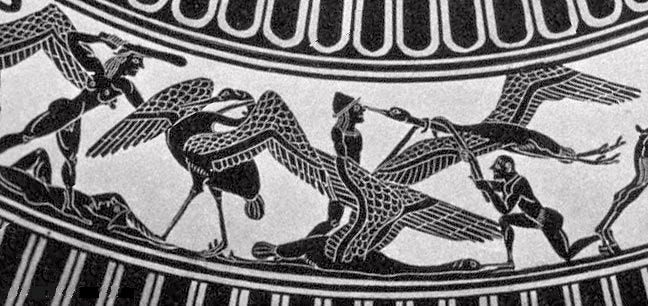

Lenny delves into the grammar of this simile by walking his reader through how other bird similes operate in the Iliad, emphasizing in part the group nature of this comparison and their place high in the sky, where predators usually roam , marking these birds as “deadly” and their “shriek [is a] war cry” (75). There is something of an inversion in this role, as Lenny notes, because cranes are not typically predatory birds in similes and this is the only extant example of massed birds compared to an attacking army. The second half of the essay examines this peculiarity.

One argument Lenny provides is based on the context of book 3 and the character of the Trojan(s) who fight in the book. He notes that soon after this passage, Paris is criticized by his brother for not being a fighter, for being a dancer/lover instead, a theme that pervades the book and is emphasized again at the end when Paris is returned to his bedroom. Cranes, in the language of Greek poetry and myth, are birds who dance. In this light, the cranes reflect the unaccustomed place of the Trojans themselves in the Iliad: “in an unaccustomed role, in an unaccustomed locale: shrieking high above the river-plains, they descend like predators upon the Pygmies” (90).

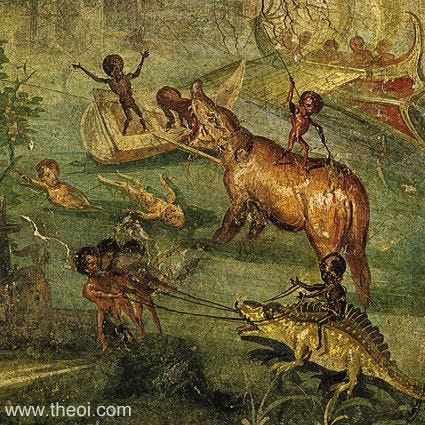

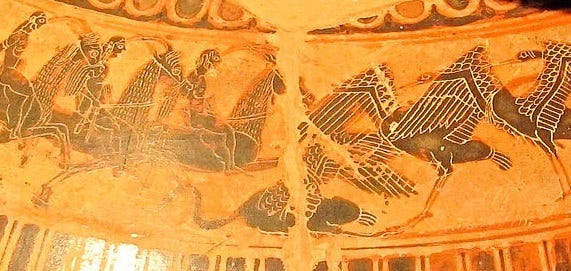

The information about the Pygmies is less clear: Lenny notes a tradition from Egypt where a tribe of people called pygmies where known for “the god’s dances” (100). There was a tradition of the war of cranes and pygmies in art outside of Homer that may or may not be related to this. I suspect that the inversion of the cranes (as Trojans) going across the ocean to battle a non-bellicose foe may be significant to the resonance of the image here. At its most extreme/absurd, we can imagine something of a dance battle, a conflict resolved in a different dimension and a world far away.

Works Mentioned

Mackie, Hilary Susan. Talking Trojan: speech and community in the Iliad. Greek Studies: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Lanham (Md.): Rowman and Littlefield, 1996.

Muellner, Leonard Charles. “The simile of the cranes and Pygmies : a study of Homeric metaphor.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. XCIII, 1990, pp. 59-101.

Ross, Shawn A. “Barbarophonos: Language and Panhellenism in the Iliad.” Classical Philology 100, no. 4 (2005): 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1086/500434.

Previous Posts on Iliad 3

1. (Re-)Starting the Trojan War: Iliad 3 and Helen as Our Guide: the Iliad and narrative traditions; Helen and the teikhoskopia

2. Heroic Appearances: Or, What Did Helen Look Like?: Physiognomy, part 2; Helen; Beauty

3. Suffering So Long for this Woman!: Various Ancient Attitudes towards Helen: More On Helen

4. Long Ago, Far Away: The Iliad and the So-Called Epic Cycle After the Canon: The Epic Cycle, Neoanalysis, Star Wars, and Homer