This post is a continuation of my substack on the Iliad. All proceeds from the substack are donated to classics adjacent non-profits on a monthly basis.

In my earlier posts on Iliad 4, I emphasized the opening scene, where Zeus toys with the other gods and entertains the idea of ending the conflict, and one part of the so-called epipolesis, where Agamemnon goes around ‘rallying’ the troops to start the war. I barely discussed the intermediary scene where the gods rekindle the war by prompting Pandaros to break the truce made in book 4 by shooting at Agamemnon.

The structure of the book ends up looking something like this:

Structure of Iliad 4

1-72 Divine Assembly, Articulation of Local Plan

72-222 Rekindling of the Conflict, Wounding of Agamemnon

233-421 Epipolesis

422-544 Battle Scene

As with earlier books, we find the action splits into smaller parts, often 3 or 4, in an analogy to the way we can break down each line of dactylic hexameter into smaller, yet still sensible parts. Each part of this book could conceivably function alone or in a different order. The first section connects us to larger narrative arcs (e.g., the Trojan War and its causes); the second creates a join between the mythical narrative and the particular story of the Iliad (indeed, providing a kind of bridge from Zeus’ “plan” in the cosmic sense to end the race of heroes and the ‘local’ Iliadic plan of having the Greeks lose to appease Achilles’ slighted honor); the third section, building on the wounding of Menelaos in the second, serves chiefly to recharacterize Agamemnon as a leader in the war and to introduce us to warriors who have not spoken much so far, but who will be primary players later (e.g. Idomeneus, Diomedes); and the final martial chaos of the book provides a bridge to the battle and aristeia of book 5.

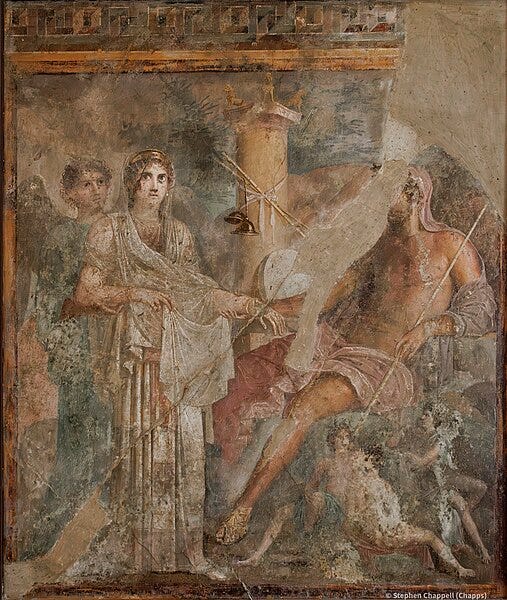

There’s a lot in this book I haven’t talked about. From the perspective of some of my recent posts attempting to imagine how Homeric heroes think (or are managed etc.). The example of Pandarus being induced to shoot Menealos and break the truce–thus providing some moral case against the Trojans–is interesting. I’d like to spend more time thinking about what Athena says and the figure she dons to persuade him, but that’s probably for the next time I go through the Iliad.

Every time I read Iliad 4 I find myself struck by Hera’s offer to Zeus after he suggests that they just have peace made between the Trojans and Greeks. On one level–if we are thinking about the overlapping motivations of mortals and gods–Hera’s response reflects the deep enmity that either side of a human conflict might feel. Just as at the end of the Odyssey there is no resolution to the cycle of vengeance between Odysseus and the suitors families, so too is there no way to resolve this war without the destruction of Troy (or the Greeks, in an alternate timeline). This is the terrible logic of violence, the inevitable outcome of revenge-fueled ‘justice’: arms are merely put aside until the next opportunity for slaughter. The Odyssey’s final dea ex machina dramatizes this; but before we can get there–or, more properly, to the reconciliations of Illad–by first witnessing the depths and consequences of holding a grudge.

So, we get to Hera’s response to Zeus.

Homer, Iliad 4.51-61

“I hold three cities dearest to me of all:

Argos, Sparta and Mykene of the wide ways.

Destroy them whenever they are hateful to your heart.

I am not standing before them and I don’t care about them.

For even if I am jealous over them and I don’t want you to destroy them,

I do not deny you in my jealousy because you are stronger than I am.

But it is not right to render my labor useless.

I am a god too, and my lineage comes from the same place as yours.

Crooked minded Kronos fathered me as the most honored of the gods

Both in terms of my birth and because I am called your wife

And you rule among the immortals”ἤτοι ἐμοὶ τρεῖς μὲν πολὺ φίλταταί εἰσι πόληες

῎Αργός τε Σπάρτη τε καὶ εὐρυάγυια Μυκήνη·

τὰς διαπέρσαι ὅτ’ ἄν τοι ἀπέχθωνται περὶ κῆρι·

τάων οὔ τοι ἐγὼ πρόσθ’ ἵσταμαι οὐδὲ μεγαίρω.

εἴ περ γὰρ φθονέω τε καὶ οὐκ εἰῶ διαπέρσαι,

οὐκ ἀνύω φθονέουσ’ ἐπεὶ ἦ πολὺ φέρτερός ἐσσι.

ἀλλὰ χρὴ καὶ ἐμὸν θέμεναι πόνον οὐκ ἀτέλεστον·

καὶ γὰρ ἐγὼ θεός εἰμι, γένος δέ μοι ἔνθεν ὅθεν σοί,

καί με πρεσβυτάτην τέκετο Κρόνος ἀγκυλομήτης,

ἀμφότερον γενεῇ τε καὶ οὕνεκα σὴ παράκοιτις

κέκλημαι, σὺ δὲ πᾶσι μετ’ ἀθανάτοισιν ἀνάσσεις.

Here, Hera shows that she is so vengeful that she is willing to give up cities that were sacred to her for the destruction of the city of Troy. Any casual reader might note that these are the very cities that have brought some of the largest contingents to Troy! Ancient scholiasts note variously that this scene provides an explanation for Hera’s anger that does not include the judgment of Paris: these are the cities that started all the problems with Helen to begin with!

Schol. bT Ad Hom. Il 51-2 51

“It is notable that the poet wants to place a probable cause for the anger on Hera and it is not that which the myth fashions, that she is angry at the Trojans because Aphrodite was honored ahead of her in the judgment over beauty, instead he says that she loves those cities over which the injustice against Helen occurred.”

ῥητέον δὲ ὅτι εὐπρεπῆ βουλόμενος περιθεῖναι αὐτῇ τὴν αἰτίαν τῆς ὀργῆς ὁ ποιητής,

καὶ οὐχ ἣν ὁ μῦθος ἀναπλάττει, ὡς ἄρα διὰ τὸ μὴ προτιμηθῆναι τῆς ᾿Αφροδίτης ἐπὶ τῇ κρίσει τοῦ κάλλους τοῖς Τρωσὶν ἐχαλέπαινεν, ἐπίτηδες ταύτας φησὶν αὐτὴν τὰς πόλεις φιλεῖν, περὶ ἃς τὸ ἀδίκημα τὸ κατὰ τὴν ῾Ελένην γέγονεν

Schol. A

“Note [that she mentions this] that they are fighting alongside the Greeks on account of these cities, not because of the judgment about beauty offered by Paris, which Homer doesn’t know about”

ὅτι τούτων τῶν πόλεων ἕνεκα συνεμάχουν τοῖς ῞Ελλησιν, οὐ διὰ τὸ ἀποκεκρίσθαι ὑπὸ ᾿Αλεξάνδρου τὸ κάλλος αὐτῶν, ὅπερ οὐκ οἶδεν ῞Ομηρος.

Others (see the bibliography below) have written well about the tension here between a “savage” goddess and the emerging concerns of the Iliad. In particular, there is a thematic arc between this book and book 24 where Hera argues against having Achilles give Hektor’s body back to his family for burial. In each scene, Hera represents that primal vengeance we often associate with chthonic deities like the Furies. In book 4, Zeus doesn’t make Hera relent, but by the end of the epic, Apollo stands to argue against her, and Zeus makes a judgment against her.

From the perspective of Hesiod’s Theogony, where Zeus stabilizes the divine realm by ensuring that each god has their own honors and place in his universe, this horse-trading of favored cities could be seen as an echo of the conflict between Agamemnon and Achilles: Hera is offering to effect a redistribution of honor through the sacrifice of a favored city. Potential strife is averted through the offer of an exchange of one geras (that token of honor and esteem) for another. There is also an argument I have read suggesting that the cosmic aspect of this exchange of cities provides an explanation for the absence of these cities in the time of the epic’s audience. Such an argument suggests that while Zeus does not agree to take these three cities immediately, but their later obliteration supports the larger motivation of Zeus’ plan to rid the earth of the race of heroes.

But the rights of the gods are more or less fixed. Their world cannot change, so there’s more going on here. From a perspective that makes Iliad 24 a crucial resolution of the epic’s themes, book 4’s dispute is anticipatory: it perpetuates the violence for the audience to experience on the way to the realization that this kind of conflict is not merely unsustainable but it is fundamentally dehumanizing in that it makes people into things and obliterates families and cities. In my own reading of the Iliad in the light of modern violence, the poem itself attempts to re-humanize, to prompt its audience to recognize the folly and the damage of war and the endless, unendurable logic of comeuppance.

In this reading, Hera’s speech should shock audiences into thinking about vengeance and divine caprice. The peril of vengeance is clear; but Hera’s caprice may hint at a theological shift: Zeus’ playfulness and the malice of other gods might just convince some mortals that we need to rely on ourselves to make our lives better, since the gods are certainly not on our side.

A Few things to read

Van Erp Taalman Kip, A. Maria. “The gods of the « Iliad » and the fate of Troy.” Mnemosyne, vol. 53, no. 4, 2000 Ser. 4, pp. 385-402.

O’Brien, Joan V.. The transformation of Hera: a study of ritual, hero and the goddess in the Iliad. Greek Studies: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Lanham (Md.): Rowman and Littlefield, 1993.

O’Brien, Joan. “Homer's savage Hera.” The Classical Journal, vol. LXXXVI, 1990-1991, pp. 105-125.

Synodinou, Katerina. “The threats of physical abuse of Hera by Zeus in the Iliad.” Wiener Studien, vol. C, 1987, pp. 13-22.

Earlier Posts on Iliad 4

Backing Up the Future: Characterization and Rivalry in Iliad 4: The Epipolesis, Agamemnon, and Rivalry

Better than our Fathers!: Theban Epic Fragments and the Homeric Iliad: Inter-mythical rivalries; Agamemnon, Diomedes and Glaukos; Book 4